Positive Health in University Teaching - a Field Report

*Corresponding Author(s):

Ottomar BahrsInstitute Of General Practice And Health Services Research, University Of Duesseldorf, Germany

Tel:+49 551398195,

Email:obahrs@gwdg.de

Background

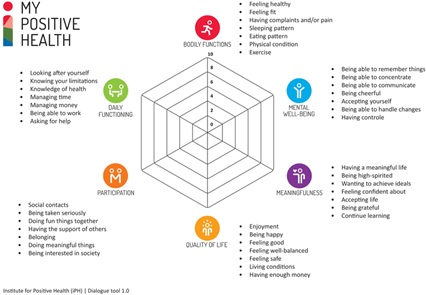

Health is more than the absence of illness. Health and illness co-exist dynamically interwoven in the life process. Health is (also) the result of a process of experience and interpretation and is, therefore, individual. In a multi-stage survey with patients and practitioners, the Dutch general practitioner Dr Machtelt Huber identified the dimensions of meaning, mental well-being, social participation, coping with everyday life and quality of life, which must be considered in addition to physical functioning and are each weighted differently [1]. The individual aspects are rarely considered in the care process, especially for people with chronic illnesses, and need to be addressed in health promotion. The "Positive Health" concept draws attention in parallel to the various dimensions and their respective significance for those affected. With the "spider's web", a method was developed that allows the description and visualisation of the patient's view of health in a pragmatic and cross-activity manner, makes resources recognisable and can be used as a basis for health-related discussions [2]. This enables a person-centred, goal-oriented dialogue and can also be used to guide action in community health promotion [3]."Positive Health" has received a great response across all activities in the Netherlands (Ministerie van Volksgeszondheid, Welzijn en Sport 2020). Experience to date shows that "Positive Health" supports a resource-saving and customised approach that promotes satisfaction and well-being for everyone involved [4]. Efforts are being made to test the "Positive Health" concept in health-related practice in Germany and reflect on this from a health science perspective. The aim of this article is to show how "Positive Health" can be used in health-related teaching at colleges and universities.

Methods

This is the lecturer's experience report. It evaluates 6 "Positive Health Talks" documentation and the overall impression of class participation and student feedback (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Positive Health Talks.

Figure 1: Positive Health Talks.

Objectives and Questions

Is "Positive Health" suitable as an essential element for teaching health models - such as salutogenesis - and resource-orientated practice in health science teaching?

- The task for the students: Report on a "Positive Health" conversation

Implementation, documentation, and report on case-related testing of the spider web graphic ("My Positive Health"):

- find a dialogue partner.

- ensure data protection and obtain informed consent for using the spider web (originals

remain with respondents). - dialogue process (primacy: active listening!)

- Opening and creating a favourable atmosphere;

- Active listening: What does "my positive health" mean for the interviewee?

- Prioritisation: Where is there a desire/need for change?

- Concretisation and clarification of possible resistance

- If necessary, reformulation and definition of the next step

- Potential supporters

- Conclusion and feedback on the interview itself.

- documentation and evaluation

- Overall picture and relationship between the dimensions.

- Changes in dialogue? Resources and risks from the perspective of those affected? Do life dreams make up the basis for prioritisation?

- Need for change from the perspective of those affected?

- Obstacles from the perspective of those affected?

- Development prospects

- Potential supporters from the perspective of the interviewee(s)?

- Evaluation of the dialogue by the participants

- summary: Did the joint discussion of the spider web graphic lead to new insights for those

affected and opened up new perspectives for action? - communicative validation (if possible and desired):

Feedback to and from the dialogue partner

- typing: Could you recognise a pattern that is also possible for other affected persons? What

recommendations for action do you derive from this?

Finding

Students from the summer semester of 2023 made the topic their own with committed and qualified keynote speeches. Subsequently, around one in six (out of 55) participants voluntarily and additionally tested the tool in an interview with a dialogue partner outside the university, documented and reflected on this and wrote a written report. The interviewees were women between 23 and 63 (∅ = 47) with different chronic illnesses and life situations.

- Example 1: In the case of chronic illness, self-acceptance, education, and destigmatisation must go hand in hand

The authors interviewed two women of different ages (23 and 46) with different illnesses and made comparisons. What the interviewees have in common is that they make a healthy impression, although both are burdened. From the outside, a possible health restriction can only be assessed to a limited extent. The interview makes it possible to understand the respective situation from the inside. Against the interviewees’ age and experiences, the interviewees focus on other resources and refer to various developmental tasks in their respective phases of life. The dreams of both interviewees reveal some commonalities that could be representative of chronically ill patients or disadvantaged groups of people in general. The wish for more educational work, an unrestricted everyday life or a banal wish to feel taken more seriously were expressed by both interviewees.

- Example 2: "At last, someone has taken me seriously." (Mrs B., 35, chronically ill since childhood)

In the conversation, a chronic overload becomes apparent, which gains momentum against the background of professional stress and the desire to make oneself indispensable in the face of a chronic illness (which is kept almost secret) through permanent responsiveness. Stigmatisation is at the heart of this. The associated risk is physically staged and thematised in the conversation, resulting in a prioritisation change in everyday life. "Finally, someone has taken me seriously." The relationship established through the interview becomes a resource and is utilised beyond the situation in mutual support [5].

- Example 3: Health-orientation has a motivating effect - hold regular discussions! (Mrs F., 63, disabled)

Completing the "Positive Health Model" was very upsetting for Mrs F. It affected her to become aware of her limitations and to deal with them "in writing". At the same time, it encouraged her to recognise what potential she still has and what is going well in her life. She found the name "My Positive Health" motivating and was pleased that the focus was not just on "this one thing", as is the case with doctors and in all forms for health and long-term care insurance companies. She would like to repeat this monthly or every three months. The student emphasises the value of asking about wishes, goals and positive influences. "Based on this experience, for example, when talking to friends or acquaintances who tell me about their illnesses, I will ask them what they would like to achieve and what they can contribute to a possible improvement. This could shift the focus from the illness to general, more comprehensive health."

- Example 4: Life is a gift (Mrs H., 47, multiple chronic illnesses)

During the conversation, it becomes clear that Mrs H has been affected by several chronic illnesses throughout her life and has been restricted in her everyday life. She has learnt to appreciate what she has but tries to maintain control as best she can and repeatedly exceeds her limits. She finds it difficult to ask for help and does not want to inform those around her about her situation.

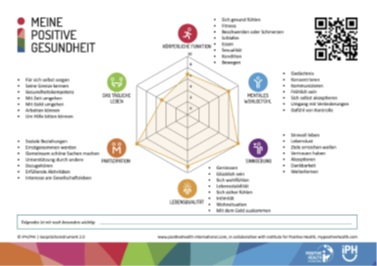

The student found the conversation "very interesting and inspiring, as I realised for myself how people often fall into the stigmas described. On the other hand, I could see that a mere diagnosis alone says nothing about how the person is doing or how this person perceives their state of health." The student attributes a strong sense of coherence to the interviewee and sees good development opportunities (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Meine Positive Gesundheit.

Figure 2: Meine Positive Gesundheit.

Discussion

First impressions are reported here. The topic has greatly interested students and reactivates a frequently primary motive for choosing a career. Members of all professional groups (nursing, physiotherapy, midwifery, public health) feel addressed, and the tool has also proven its worth in the pre-professional field: a teaching interview has turned into a supportive relationship that utilises existing skills without explicitly assigning roles. I suggest that "positive health" can also become a guiding principle in civic assistance (family help, neighbourhood help, volunteering, self-help) if the necessary skills can be used.

Take Home Message

Positive Health promotes a salutogenic orientation and is an opportunity for a theory- and experience-based orientation of health-related practice. Personal interview experience and its structured and self-reflective processing facilitate access to person-centredness, appreciation of subjective concepts of health and illness, perception of resources and the importance of shaping relationships, and biographical and social aspects of health inequality. Overall, this promotes a holistic understanding of health and illness.

References

- Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, Horst H, Jadad AR, et al. (2011) How should we define health? BMJ 343: 235-237.

- Bock LA, Noben CYG, Yaron G, George ELJ, Masclee AAM, et al. (2021) Positive Health dialogue tool and value-based healthcare: a qualitative exploratory study during residents’ outpatient consultations. BMJ Open 11: 052688.

- Wietmarschen HA, Staps S, Meijer J, Flinterman JF, Jong MC (2022) The Use of the Bolk Model for Positive Health and Living Environment in the Development of an Integrated Health Promotion Approach: A Case Study in a Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhood in The Netherlands. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19: 2478.

- Lemmen CHC, Yaron G, Gifford R, Spreeuwenberg MD (2021) Positive Health and the happy professional: a qualitative case study. BMC Fam Pract 22: 159.

- Möller V (2024) “My positive Health“ - Eine Möglichkeit zur Verbindung von Theorie und Erfahrungslernen aus Sicht einer Studierenden. Der Mensch – Zeitschrift für Salutogenese und anthropologische Medizin 63: 36-41.

Citation: Bahrs O (2024) Positive Health in University Teaching - a Field Report. J Altern Complement Integr Med 10: 483.

Copyright: © 2024 Ottomar Bahrs, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.