Posterior Cranial Vault Expansion Remodeling for the Treatment of Various Craniosynostosis in Children

*Corresponding Author(s):

Zong Jian AnDepartment Of Surgical Center, Qingdao Women & Children's Hospital, Qingdao 266034, China

Email:qdfesjwk@126.com

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of posterior cranial vault expansion remodeling (PCVR) in treating various types of craniosynostosis in children.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed clinical data from seven patients with diverse craniosynostosis types who underwent posterior cranial vault expansion remodeling between February 2018 and September 2023. The cohort included five boys and two girls, aged 10 to 23 months. Preoperative three-dimensional computed tomography (3D-CT) scans were assessed. The sample comprised one case each of sagittal, unilambdoid, bilambdoid, bicoronal craniosynostosis, Pfeiffer syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, and combined sagittal and unilambdoid craniosynostosis. Two patients with Chiari malformation (CM) (type I) required additional foramen magnum decompression. Patients with bicoronal craniosynostosis and Pfeiffer syndrome underwent subsequent frontal-orbital advancement and remodeling.

Results

No fatalities, sinus injuries, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, or infections of the skull and scalp occurred. The mean follow-up duration was 16.6 months (range: 7–42 months). All patients exhibited significant improvements in skull deformities. Volumetric analysis one-week post-surgery indicated an increase in cranial volume from 45 to 94 cm3, with a mean increase of 69.6 cm3.

Conclusion

Posterior cranial vault expansion remodeling proves to be an effective treatment for syndromic craniosynostosis and lambdoid craniosynostosis. It is also beneficial for treating sagittal and other craniosynostosis associated with deformities of the posterior cranial fossa.

Keywords

Craniosynostosis; Surgical treatment; Cranial vault remodeling; Posterior cranial vault expansion

Introduction

Craniosynostosis, also known as cranio stenosis, results from the premature closure of one or more cranial sutures, leading to deformities in head appearance and restricted brain development. The condition occurs in approximately 1 in 2,000 to 2,500 births [1].The presentations of craniosynostosis vary widely. Syndromic craniosynostosis involves multiple sutures and results in severe craniofacial deformities and increased intracranial pressure [2]. Surgery is the sole treatment, aimed at expanding the cranial cavity, reducing intracranial pressure, and enhancing appearance while facilitating normal skull and brain development. Historically, surgeries targeting the expansion and reconstruction of the anterior cranial fossa were common [3]. However, it was later observed that such surgeries were often ineffective for complex cases involving severe brachycephaly, leading to deformity recurrence and necessitating additional operations [4]. Consequently, techniques focusing on the expansion and remodeling of the posterior cranial fossa have been adopted for their significant improvements in the fossa’s morphology, enhanced cranial capacity, and reduced intracranial pressure [5,6]. Our center has successfully applied these techniques to treat seven cases of craniosynostosis. In addition, we aimed to assess the efficacy of PCVR in treating various types of craniosynostosis in children.

Data and Methods

General Information

This study included seven children with craniosynostosis who underwent posterior cranial fossa expansion and remodeling surgery, consisting of five males and two females aged 10 to 23 months. Preoperative diagnostic measures included CT scans and three-dimensional skull reconstruction. The types of craniosynostosis varied: one case each of sagittal suture, bilateral coronal suture, bilateral lambdoid suture, unilateral lambdoid suture, combined sagittal and unilateral lambdoid suture craniosynostosis, Crouzon syndrome, and Pfeiffer syndrome. Notably, the children exhibited varying degrees of posterior cranial fossa dysplasia, with Crouzon syndrome presenting with hydrocephalus and CM, and bilateral lambdoid suture craniosynostosis also associated with CM.

Surgical Methods

Preoperatively, an evaluation of the airway was conducted. All operations were performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation in the prone position. The forehead and eyes were protected with functional dressings to prevent pressure injury. The extent of surgical intervention depended on the severity of deformity and the preoperative assessment of intracranial pressure. A coronal W-shaped incision was made at the cranial vertex, adjusted anteriorly if a second-stage frontal orbital surgery was anticipated, or a Y-shaped incision for posterior fossa or combined CM surgeries to facilitate lower skull osteotomy. The incision was designed to allow sufficient exposure of the posterior cranial fossa and cranial vertex while minimizing increased scalp tension post-expansion.

After skull exposure, drill holes and mill the occipital bone flap from inside the lambdoid suture to the occipital protuberance or above the foramen magnum. Gently separate the bone flap from the dura mater using a dissector, then remove it while protecting the transverse sinus and torcular herophili. Reshape and rotate the removed bone flap as required, making radial incisions for a further increase of the skull expansion and intracranial volume increase. The bone flap is then fixed to the skull with resorbable stitches. For children with high intracranial pressure and skull was tightly adhered to the dura, the increased intracranial pressure can drive bone structures expansion once relieved from their attachment to the adjacent region. So, after satisfactory milling, fix the expanded flap with connecting pieces to the skull without further separation to protect the torcular herophili. For cases with abnormal cranio-cervical junction development and associated CM, perform foramen magnum decompression. In cases like sagittal suture craniosynostosis, create stamp-shaped incisions in the parietal and both temporal bones, extending from the rear of the anterior fontanelle forward to the temporal squamous sutures. Following osteotomy and skull shaping, suture the periosteum, place a subcutaneous scalp drainage tube, and close the scalp incision.

Postoperative management and measurement

After the surgery, children were admitted to the ICU with tracheal intubation, receiving analgesia and sedation for 1 to 2 days. Third-generation cephalosporins and hemostatic agents were administered routinely. One-week post-surgery, a head CT scan was performed. Cranial cavity volume was measured using preoperative and postoperative CT imaging data (DICOM) with Mimics Medical 19.0 software.

Statistical methods

Data on cranial cavity volume before and one-week post-surgery were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 22.0. Statistical analysis was conducted using the mean and standard deviation (x±s) and t-tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All surgical procedures were successfully completed with no fatalities. The appearance of cranial deformities showed significant improvement postoperatively. The follow-up period ranged from 7 to 42 months, averaging 16.6 months, with no severe complications such as bone flap necrosis, displacement, or cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Prior to surgery, the child with Crouzon syndrome exhibited hydrocephalus and underwent a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt to reduce intracranial pressure; surgery on the skull followed three months later. Two children required secondary surgeries; one for bilateral coronal suture craniosynostosis involved a subsequent frontal orbital remodeling eight months after initial surgery to alleviate cranial pressure. The other, with Pfeiffer syndrome, underwent expansion of the frontal and parietal regions seven months later due to severe deformities.

One-week post-surgery, when stable, the children’s cranial cavity volumes were reassessed via head CT. Comparative measurements showed preoperative volumes at 1236.42 ± 181.45 ml and postoperative volumes at 1306.00 ± 177.14 ml. The mean increase in cranial cavity volume was 69.57 ml (ranging from 45 to 94 ml, Table 1), with a statistically significant difference (t = -10.108, P < 0.001).

|

Case |

Sex |

Age |

Category |

Preoperative cerebral volume (cm3) |

Cerebral volume one week after surgery (cm3) |

|

1 |

Male |

10 months |

Sagittal suture craniosynostosis |

1228 |

1322 |

|

2 |

Male |

12 months |

Pfeiffer syndrome |

970 |

1039 |

|

3 |

Female |

23 months |

Bilateral lambdoid suture craniosynostosis |

1389 |

1473 |

|

4 |

Male |

16 months |

Sagittal suture and lambdoid suture |

1215 |

1282 |

|

5 |

Male |

12 months |

Bilateral coronal sutures |

1089 |

1169 |

|

6 |

Male |

18 months |

Unilateral lambdoid suture |

1243 |

1288 |

|

7 |

Female |

16 months |

Crouzon syndrome |

1521 |

1569 |

Table 1: Basic information and cranial cavity volumes pre- and post-operation for 7 children.

Typical Case

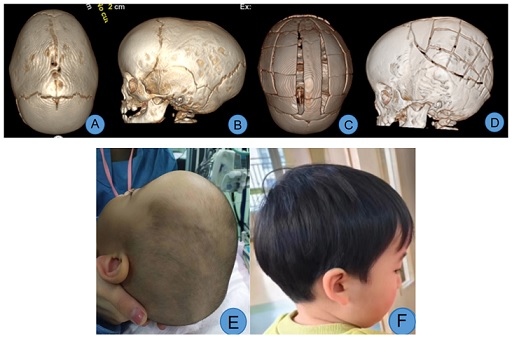

Case 1: Male, 10 months old. Preoperative three-dimensional CT revealed sagittal suture craniosynostosis, characterized by a long and narrow head, primarily due to posterior cranial fossa stenosis. After admission, relevant examinations were completed. The child underwent general anesthesia during which posterior cranial fossa and parietal bone expansion and remodeling were performed. Postoperatively, the morphology of the posterior cranial fossa and skull was significantly improved, with a considerable increase in cranial cavity volume (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A, B. Preoperative view showing sagittal suture craniosynostosis, a well-developed frontal region, and a narrow posterior cranial fossa; C, D. Views from the top and side on the 7th day post-surgery, showing improved posterior cranial fossa morphology and expanded cranial cavity volume; E. Preoperative head appearance, displaying a long and narrow head and a narrow occipitoparietal region; F. Front and side views 26 months post-surgery, demonstrating corrected occipitoparietal stenosis and a reduced anteroposterior head diameter.

Figure 1: A, B. Preoperative view showing sagittal suture craniosynostosis, a well-developed frontal region, and a narrow posterior cranial fossa; C, D. Views from the top and side on the 7th day post-surgery, showing improved posterior cranial fossa morphology and expanded cranial cavity volume; E. Preoperative head appearance, displaying a long and narrow head and a narrow occipitoparietal region; F. Front and side views 26 months post-surgery, demonstrating corrected occipitoparietal stenosis and a reduced anteroposterior head diameter.

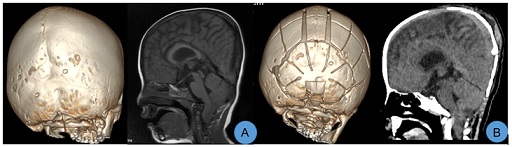

Case 2: Female, 23 months old. Preoperative three-dimensional CT showed bilateral lambdoid suture craniosynostosis, a flat and dysplastic posterior cranial fossa, and CM. After admission, relevant examinations were completed. Under general anesthesia, expansion and remodeling of the posterior cranial fossa, along with foramen magnum decompression, were performed. Significant improvement in the morphology of the posterior cranial fossa was noted post-surgery (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A. Preoperative images displayed bilateral lambdoid suture craniosynostosis and CM, with a flat posterior cranial fossa; B. CT scans taken on the 7th day post-surgery showed significant improvement in the morphology of the posterior cranial fossa and effective correction of the CM.

Figure 2: A. Preoperative images displayed bilateral lambdoid suture craniosynostosis and CM, with a flat posterior cranial fossa; B. CT scans taken on the 7th day post-surgery showed significant improvement in the morphology of the posterior cranial fossa and effective correction of the CM.

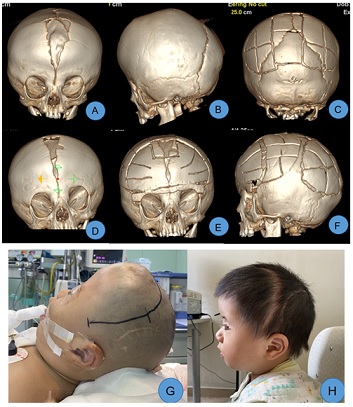

Case 3: Male, 1 year old. Preoperative CT scans revealed bilateral coronal suture craniosynostosis, brachycephaly, and frontal bone dysplasia. Following admission, the first stage of surgery involving posterior cranial fossa expansion and remodeling was performed. Postoperatively, intracranial pressure was reduced, and frontal bone development was satisfactory. Eight months later, a second-stage surgery for frontal orbital advancement and skull remodeling was undertaken. The postoperative appearance of the head was satisfactorily restored (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A, B. Preoperative CT showed bilateral coronal suture craniosynostosis with a significant frontal bone defect; C. Improvements in the posterior cranial fossa morphology were observed 7 days after the first-stage surgery; D. 8 months post-surgery, marked development of the frontal bone was noted; E, F. After the second-stage surgery, the head appearance was satisfactorily recovered, and cranial cavity volume had expanded significantly, G. Before the second-stage surgery, the frontal part appeared short and flat; H. 3 months post-surgery, reexamination showed satisfactory frontal orbital protrusion.

Figure 3: A, B. Preoperative CT showed bilateral coronal suture craniosynostosis with a significant frontal bone defect; C. Improvements in the posterior cranial fossa morphology were observed 7 days after the first-stage surgery; D. 8 months post-surgery, marked development of the frontal bone was noted; E, F. After the second-stage surgery, the head appearance was satisfactorily recovered, and cranial cavity volume had expanded significantly, G. Before the second-stage surgery, the frontal part appeared short and flat; H. 3 months post-surgery, reexamination showed satisfactory frontal orbital protrusion.

Discussion

Although controversies persist regarding the timing and surgical techniques for treating craniosynostosis, ongoing refinement of surgical methods and deeper understanding of the condition have established that cranial cavity volumes in children with craniosynostosis are generally smaller than those in normal children [7]. Rapid brain development in infants and young children is constricted by craniosynostosis, which compresses the venous sinuses and disrupts cerebrospinal fluid circulation, leading to increased intracranial pressure [8]. Thus, early expansion of cranial capacity and reduction of intracranial pressure are critical objectives in craniosynostosis treatment. Initially, many experts favored anterior cranial fossa expansion surgeries, such as frontal orbital advancement. However, it was subsequently discovered that for syndromic and complex craniosynostosis, the recurrence rate following anterior cranial fossa reconstruction is relatively high, often necessitating reoperations [4,9]. For severe brachycephaly, posterior cranial fossa dysplasia, interventions in the posterior cranial fossa have gradually been implemented with favorable outcomes. Currently, posterior cranial fossa expansion surgery is considered the standard first-stage surgical approach for treating syndromic and complex craniosynostosis [10].

The posterior cranial fossa expansion techniques primarily involve floating bone flap incisions of the posterior cranial fossa, skull distraction by implanting distractors or auxiliary springs, and extensive skull remodeling of relatively fixed bone flaps. The primary goal of these surgeries is to early and adequately expand the cranial cavity volume to reduce intracranial pressure, enhance appearance, and address functional disorders caused by restricted brain development. The posterior cranial fossa skull exhibits greater growth potential and can more effectively increase the cranial cavity volume post-surgery [11]. Studies measuring anterior and posterior cranial cavity volumes in children under two years old indicate that in normal children, the volume of the posterior cranial fossa increases faster than that of the anterior within this age range. Therefore, for children with syndromic craniosynostosis accompanied by posterior cranial fossa flattening or cerebellar tonsillar herniation, performing posterior cranial fossa expansion before the age of two aligns better with physiological development characteristics and may be more effective [12]. For cases of syndromic brachycephaly, posterior cranial fossa expansion and remodeling can increase cranial cavity volume by approximately 35%, compared to anterior cranial fossa surgeries of similar extent [13]. The potential for expanding cranial cavity volume through posterior vault distraction osteogenesis (PVDO) is significant. Kim et al. found that among eight cases of PVDO and five cases of skull remodeling, cranial cavity volume increased by an average of 20.9% and 10.7% respectively after surgery [14]. However, some literature reports no significant differences between techniques. Nowinski compared cranial cavity volumes after posterior cranial fossa floating bone flap surgeries and distraction osteogenesis, finding postoperative volume increases of 13% and 24% respectively in floating bone flap surgeries, and 22% and 29% respectively in distraction osteogenesis [15]. Breakey et al. measured the volumes in 7 cases of PCVR and 12 cases of distraction osteogenesis, with postoperative increases of 14.0 ± 12.5% and 13.8 ± 5.0% respectively [16]. Among the 7 cases in this study, cranial cavity volume increased from 45 to 94 ml one week after surgery, with an average increase of 69.57 ml, and the difference was relatively large, which the author believes is related to the extent of surgical remodeling and age at surgery.

Posterior cranial fossa expansion surgery not only effectively increases cranial cavity volume but also alleviates frontal pressure, enhances frontal development, and proptosis in syndromic craniosynostosis, potentially delaying or obviating the need for second-stage frontal surgeries [17]. In a case of bilateral coronal suture craniosynostosis with frontal bone dysplasia, initial posterior cranial fossa expansion reduced intracranial pressure and fostered frontal skull development, thus facilitating subsequent frontal orbital advancement surgery. Similarly, a case of Pfeiffer syndrome exhibited improved frontal development after the first-stage surgery, leading to a positive outcome following the second-stage procedure. Additionally, for lambdoid suture craniosynostosis and complex multi-suture syndromes, the likelihood of associated CM can exceed 50%, with rates in complex syndromes reaching above 70% [18,19]. For such cases, posterior cranial fossa expansion significantly increases fossa volume, enhances venous sinus reflux and cerebrospinal fluid circulation, aiding in the amelioration of CM and syringomyelia [20]. Scoot et al. reported treating craniosynostosis with CM by combining posterior cranial fossa remodeling with foramen magnum decompression. Among 14 children treated, CM was resolved in five, improved in five, and stabilized in four without further deterioration [21]. Currently, this surgery is the primary method for treating children with craniosynostosis and CM. Given that a narrow foramen magnum is a key factor in CM, it is recommended to routinely perform foramen magnum decompression to optimize outcomes.

For non-syndromic bilateral or unilateral lambdoid suture craniosynostosis, and multi-suture craniosynostosis involving the lambdoid suture, posterior cranial fossa expansion and remodeling surgery can effectively enhance the appearance of the posterior cranial fossa and reduce intracranial pressure [22]. However, most cases of syndromic craniosynostosis involve not only restricted frontal orbital growth due to coronal suture involvement but also significant posterior cranial fossa dysplasia due to abnormal cranial base bone development and compensatory changes in other skull areas, including the lambdoid suture. Thus, remodeling of the posterior cranial fossa is crucial, particularly for children with associated cerebellar tonsillar herniation and severe occipital digital impressions [23]. The clinical presentations of scaphocephaly from sagittal suture craniosynostosis are varied, with some cases showing progressive worsening due to incomplete early closure of the sagittal suture. Depending on the closure location and the child’s age, these can predominantly manifest as posterior cranial fossa deformities. For these cases, occipital remodeling is also necessary [24]. Goodrich et al. recommended prioritizing posterior cranial fossa surgery for scaphocephaly with a bullet-like narrow and prominent parieto-occipital region [25]. Khechoyan et al. conducted mid-posterior cranial fossa expansion and remodeling on 43 infants with sagittal suture craniosynostosis. Following a two-year follow-up, all frontal deformities associated with sagittal suture craniosynostosis were observed to normalize [26]. Massenburg et al. addressed 91 cases of sagittal suture craniosynostosis with posterior cranial fossa surgery, and although some cases retained a narrow cranial vertex postoperatively, frontal deformity improvement was noted over two years [27]. Markiewicz et al. also observed similar outcomes and recommended prioritizing posterior cranial fossa expansion and skull reconstruction for children older than six months with sagittal suture craniosynostosis [28]. In this cohort, one child with sagittal suture craniosynostosis showed good frontal development but poor posterior cranial fossa growth. After mid-posterior cranial fossa expansion and remodeling, significant improvement in head appearance was noted during the follow-up.

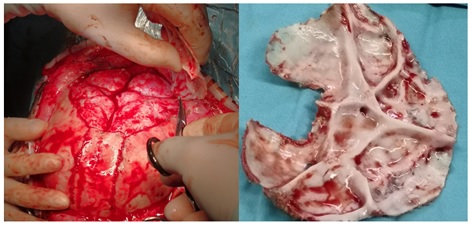

Compared to PVDO, PCVR involves extensive detachment of the skull from the dura mater surface, posing risks of damaging the dura mater and venous sinuses. This method has disadvantages including significant surgical trauma, prolonged operation times, and excessive intraoperative bleeding [29]. Some scholars recommend preoperative 3D CT venography or MRV to identify the position of the venous sinuses and exclude the presence of variant occipital sinuses, thereby reducing the risk of intraoperative venous sinus injury [30]. In this cohort, three cases underwent extensive posterior cranial fossa bone flap dissociation. Despite high intracranial pressure causing uneven compression and adhesion of the skull to the dura mater, careful dissociation prevented venous sinus injuries (Figure 4). For children with higher intracranial pressure, floating bone flaps without dura mater dissection may be employed to prevent venous sinus injury. However, such flaps can only expand passively through brain tissue expansion, and the postoperative shaping effect is suboptimal, significantly influenced by body position, with a high probability of postoperative recurrence. When performing floating bone flaps, absorbable connecting pieces can be used to fix and elevate the flaps above the torcular herophili, or fence-shaped incisions can be made on surrounding bone flaps to induce greenstick fractures and improve outcomes. Although PVDO can increase cranial cavity volume more significantly than PCVR, deformities like parieto-occipital stenosis, mere anterior-posterior expansion may not yield satisfactory cranial appearance, and lateral shaping should be considered. PCVR not only increases the anteroposterior diameter of the skull but also alleviate parieto-occipital stenosis, reduce skull height, and improve oxycephaly. Both the postoperative cranial index and the asymmetry index of plagiocephaly have shown significant improvements [31]. PVDO with higher rates of infection when compared PCVR due to the exposure of distractors. Especially for patients with hydrocephalus who have undergone ventricular shunting, PVDO will increase shunt failure and infection that usually need for additional intervention [32]. Additionally, distraction surgery poses risks of device fracture and requires regular adjustment of the traction device along with a secondary surgery to remove the extender, leading to a prolonged treatment cycle. Reports suggest that the incidence of postoperative complications, such as surgical incision infection and device fracture, can be as high as 32.2% following distraction surgery, which is higher than that following posterior cranial fossa remodeling (5% - 11%) [33]. Among the seven children in this study, there were no cases of venous sinus or dura mater injury, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, or postoperative infections, indicating that PCVR is relatively safe and the risks are manageable.

Figure 4: Due to the high intracranial pressure, the brain tissue is significantly compressed, and the skull appears uneven.

Figure 4: Due to the high intracranial pressure, the brain tissue is significantly compressed, and the skull appears uneven.

Regarding surgical timing, no unified standard currently exists. The main factors influencing the timing include the type of craniosynostosis, intracranial pressure, and the skull’s development and shaping potential. Most scholars advocate for surgery between 6-12 months to achieve optimal deformity correction and minimize the risk of recurrence; however, surgeries performed between 8-24 months can also yield a relatively good therapeutic effect [22,34]. For infants with thin or honeycomb-like skulls, those with posterior cranial fossa dysplasia immediately after birth or with rapid progression within one month, free bone flap floating expansion surgery is recommended to decrease intracranial pressure and facilitate development for a subsequent surgery [35]. For multi-suture craniosynostosis and some syndromic cases, depending on intracranial pressure assessments, the first-stage posterior cranial fossa surgery might be performed at 3-4 months, with a second-stage surgery approximately six months later, based on developmental progress. However, for children operated on within 6 months, regular reexaminations are necessary to monitor for recurrence [22].

The sample size of this study is relatively small, and more extensive studies are required. Additionally, there is a lack of long-term follow-up, particularly regarding brain development during school age.

Conclusion

Posterior cranial fossa expansion and remodeling surgery promptly improves skull appearance, effectively reduces intracranial pressure, increases cranial cavity volume, and supports frontal area development, thus preparing children for secondary surgery. This technique is not only beneficial for lambdoid suture craniosynostosis and various syndromic forms but also achieves satisfactory results for other craniosynostosis types accompanied by posterior cranial fossa dysplasia.

References

- Di Rocco F, Arnaud E, Renier D (2009) Evolution in the frequency of nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr 4: 21-25.

- Taylor JA, Bartlett SP (2017) What’s new in syndromic craniosynostosis surgery? Plast Reconstr Surg 140: 82e–93e.

- Di Rocco C, Paternoster G, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Tamburrini G (2012) Anterior plagiocephaly: epidemiology, clinical findings,diagnosis, and classification. A review. Childs Nerv Syst 28: 1413-1422.

- Selber JC, Brooks C, Kurichi JE, Temmen T, Sonnad SS, et al. (2008) Long-term results following fronto-orbital reconstruction in nonsyndromic unicoronal synostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg 121: 251e-260e.

- Derderian CA, Bartlett SP (2012) Open cranial vault remodeling: the evolving role of distraction osteogenesis. J Craniofac Surg 23: 229-34.

- Sgouros S, Goldin JH, Hockley AD, Wake MJ (1996) Posterior skull surgery in craniosynostosis. Childs Nerv Syst 12: 727-733.

- Sgouros S, Hockley AD, Goldin JH, Wake MJ, Natarajan K (1999) Intracranial volume change in craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg 91: 617-625.

- Tamburrini G, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Gasparini G, Pelo S, et al. (2012) Complex craniosynostoses: a review of the prominent clinical features and the related management strategies. Childs Nerv Syst 28: 1511-1523.

- Wong GB, Kakulis EG, Mulliken JB (2005) Analysis of frontoorbital advancement for Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer, and Saethre–Chotzen syndromes. Plast Reconstr Surg 105: 2314-2323.

- Di Rocco F (2000) Introduction to the focus session on posterior vault surgery in craniosynostosis. Childs Nerv Syst 37: 3091-3092.

- Spruijt B, Rijken BFM, den Ottelander BK, Joosten KFM, Lequin MH, et al. (2016) First vault expansion in apert and Crouzon-Pfeiffer syndromes: Front or back[J]? Plast Reconstr Surg 137: 112e-121e.

- Ji Min, Liu Xiangqi, Li Jun (2018) Study on the growth of intracranial volumes in normal children of different ages. Chin J Plast Surg 34: 829-833.

- Choi M, Flores RL, Havlik RJ (2012) Volumetric analysis of anterior versus posterior cranial vault expansion in patients with syndromic craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg 23: 455-458.

- Kim SW, Shim KW, Plesnila N, Kim YO, Choi JU, et al. (2007) Distraction vs remodeling surgery for craniosynostosis. Childs Nerv Syst 23: 201-206.

- Nowinski D, Di Rocco F, Renier D, SainteRose C, Leikola J, et al. (2012) Posterior cranial vault expansion in the treatment of craniosynostosis. Comparison of current techniques. Childs Nerv Syst 28: 1537-1544.

- Breakey RWF, Mercan E, van de Lande LS, Sidpra J, Birgfeld C, et al. (2023) Two-Center Review of Posterior Vault Expansion following a Staged or Expectant Treatment of Crouzon and Apert Craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg 151: 615-626.

- Maaten ter NS, Mazzaferro DM, Wes AM (2018) Craniometric analysis of frontal cranial morphology following posterior vault distraction. J Craniofac Surg 29: 1169-1173.

- Strahle J, Muraszko KM, Buchman SR, Kapurch J, Garton HJ, et al. (2011) Chiari malformation associated with craniosynostosis. Neurosurg Focus 31: E2.

- Cinalli G, Spennato P, Sainte-Rose C, Arnaud E, Aliberti F, et al. (2005) Chiari malformation in craniosynostosis. Childs Nerv Syst 21: 889-901.

- Cinalli G, Russo C, Vitulli F, Parlato RS, Spennato P, et al. (2022) Changes in venous drainage after posterior cranial vault distraction and foramen magnum decompression in syndromic craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr 22: 1-12.

- Scott WW, Fearon JA, Swift DM, Sacco DJ (2013) Suboccipital decompression during posterior cranial vault remodeling for selected cases of Chiari malformations associated with craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr 12: 166-170.

- Ros B, Iglesias S, Selfa A, Ruiz F, Arráez MÁ (2021) Conventional posterior cranial vault expansion: indications and results-review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 37: 3149-3175.

- Rottgers SA, Ganske I, Citron I, Proctor M, Meara JG, et al. (2018) Single-stage Total Cranial Vault Remodeling for Correction of Turricephaly: Description of a New Technique. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 6: e1800.

- Chaisrisawadisuk S, Moore MH (2021) Posterior Cranial Vault Manifestations in Nonsyndromic Sagittal Craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg 32: 2273-2276.

- Goodrich JT, Tepper O, Staffenberg DA (2012) Craniosynostosis: posterior two-third cranial vault reconstruction using bioresorbable plates and a PDS suture lattice in sagittal and lambdoid synostosis. Childs Nerv Syst 28: 1399-1406.

- Khechoyan D, Schook C, Birgfeld CB, Khosla RK, Saltzman B, et al. (2012) Changes in frontal morphology after single-stage open posteriormiddle vault expansion for sagittal craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg 129: 504-516.

- Massenburg BB, Mercan E, Shepard E, Birgfeld CB, Susarla SM, et al. (2023) Morphometric Outcomes of Nonsyndromic Sagittal Synostosis following Open Middle and Posterior Cranial Vault Expansion. Plast Reconstr Surg 151: 844-854.

- Markiewicz MR, Recker MJ, Reynolds RM (2022) Management of Sagittal and Lambdoid Craniosynostosis: Open Cranial Vault Expansion and Remodeling. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 34: 395-419.

- DI Rocco F, Licci M, Paasche A, Szathmari A, Beuriat PA, et al. (2021) Fixed posterior cranial vault expansion technique. Childs Nerv Syst 37: 3137-3141.

- Johns FR, Jane JA Sr, Lin KY (2000) Surgical approach to posterior skull deformity. Neurosurg Focus 9: e4.

- Schulz M, Spors B, Haberl H, Thomale UW (2014) Results of posterior cranial vault remodeling for plagiocephaly and brachycephaly by the meander technique. Childs Nerv Syst 30: 1517-1526.

- Azzolini A, Magoon K, Yang R, Bartlett S, Swanson J, et al. (2020) Ventricular shunt complications in patients undergoing posterior vault distraction osteogenesis. Childs Nerv Syst 36: 1009-1016.

- Khansa I, Drapeau AI, Pearson GD (2023) Posterior Cranial Distraction in Craniosynostosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 13:10556656231168548.

- Utria AF, Lopez J, Cho RS, Mundinger GS, Jallo GI, et al. (2016) Timing of cranial vault remodeling in nonsyndromic craniosynostosis: a single-institution 30-year experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr 18: 629-634.

- Tamburrini G, Offi M, Massimi L, Frassanito P, Bianchi F (2021) Posterior vault "free-floating" bone flap: indications, technique, advantages, and drawbacks. Childs Nerv Syst 37: 3143-3147.

Citation: Yuan Y, Sun Y, Li Z, Gao F, Xu W, et al. (2025) Posterior Cranial Vault Expansion Remodeling for the Treatment of Various Craniosynostosis in Children. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 12: 135.

Copyright: © 2025 Yi Yuan, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.