Potential Role of soil Parameters in Quality Formation of 1-Year-Old Ginseng Based on Correlation Analysis

*Corresponding Author(s):

Changbao ChenJilin Ginseng Academy, Changchun University Of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, China

Email:ccb2o21@126.com

Ye Qiu

College Of Pharmacy, Changchun University Of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, China

Email:ccyeqiu@163.com

Tao Zhang

College Of Pharmacy And Jilin Ginseng Academy, Changchun University Of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, China

Email:zhangtaoccucmedu@126.com

Abstract

The most critical year for cultivating ginseng is from sowing to growth until one year old, but the soil factors that affect 1-year-old ginseng are not yet clear. This study collected ginseng from farmland with repeated Planting of Ginseng (RB) and with previously planted corn where the aboveground part showed healthy (FG) and unhealthy (FB), and measured the root trait indicators and ginsenoside content. At the same time, the physicochemical properties and enzyme activities of rhizosphere soil were determined, and the data were analyzed by difference and correlation analysis. The results showed that the trait indicators of FG were higher than those of RB and FB, and the contents of most ginsenosides in RB were higher than those in FG and FB. Among them, the content of total ginsenosides in RB (6.91 mg/g) was 1.72 and 1.22 times that of FG (4.02 mg/g) and FB (5.68 mg/g), respectively. The soil of FB had high nutrient, while RB had low nutrient, mainly reflected in the content of Ca2+, Mg2+, La, Ce, Mn, Pr. Correspondingly, FB had significantly higher enzyme activity and RB the opposite. The differences in soluble organic carbon, total boron, β-amylase, and α-glucosidase were characteristic factors of soil differences. The correlation analysis results showed that soil moisture content was a common factor affecting the quality indicators of ginseng. Compared with constant elements, rare earth elements (Sm, La, Tb, Nd) had a higher correlation with ginseng quality indicators in FG. In summary, both relatively high and low soil nutrients were not conducive to the healthy growth of ginseng, and moisture content was the principal factor in its growth. At the same time, attention should be paid to the role of rare earth elements in the formation of ginseng quality.

Abbreviations

TG: Total Ginsenoside

BD: Soil Bulk Density

FWC: Field Water Capacity

MWC: Soil Mass Water Content

AGG: Soil Aggregates

EC: Electrical Conductivity

A-N: Alkaline Hydrolysis Nitrogen

A-K: Available Potassium

Ca-P: Calcium Bound Phosphorus

Fe-P: Iron Bound Phosphorus

Al-P: Aluminum Bound Phosphorus

O-P: Occluded Phosphorus

A-P: Available Phosphorus

I-P: Inorganic Phosphorus

EOC: Easily Oxidizable Organic Carbon

SOC: Organic Carbon

E-TA: Exchangeable Total Acid

E-H+: Exchangeable Hydrogen Ion

E-Al3+: Exchangeable Aluminum Ion

A-B: Available Boron

A-S: Available Sulfur

A-Si: Available Silicon

NH4+-N: Ammonium Nitrogen

NO3--N: Nitrate Nitrogen

C-Fe: Complex Iron

Ca2+: Calcium Ions

Mg2+: Magnesium Ions

SO42-: Sulfate Ion

Cl-: Chloride Ion

HCO3-: Bicarbonate Ion

CEC: Cation Exchange Capacity

T-B: Total Boron

T-Mn: Total Manganese

T-Ti: Total Titanium

T-Ca: Total Calcium

T-Mg: Total Magnesium

T-Fe: Total Iron

T-Al: Total Aluminum

T-Si: Total Silicon

T-Zn: Total Zinc

T-Eu: Total Europium

T-La: Total Lanthanum

T-Ce: Total Cerium

T-Pr: Total Praseodymium

T-Nd: Total Neodymium

T-Sm: Total Samarium

T-Gd: Total Gadolinium

T-Tb: Total Terbium

T-Dy: Total Dysprosium

T-Ho: Total Holmium

T-Er: Total Erbium

T-Tm: Total Thulium

T-Yb: Total Ytterbium

T-Lu: Total Lutetium

T-Y: Total Yttrium

DHA: Dehydrogenase

Phy: Phytase

ASF: Arylsulfatase

UR: Uricase

PPO: Polyphenol Oxidase

POD: Peroxidase

APX: Ascorbate Peroxidase

LAC: Lacase

PAL: L-Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase

FDA: Fluorescein Diacetate Hydrolase

HR: Hydroxylamine Reductase

β-Glu: β -Glucosidase

α-Glu: α -Glucosidase

SOD: Superoxide Dismutase

GLS: Glutaminase

ASP: L-Asparaginase

AMY: Amylase

α-AMY: α - Amylase

β-AMY: β - Amylase

Cel: Cellulase

Inv: Invertase

ACP: Acid Phosphatase

NR: Nitrate Reductase

CAT: Catalase

NUC: Ribonuclease

Ure: Urease

Prot: Acid Protease

Introduction

Ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Mey) is the most important medicine in Oriental Medicine. Ginseng has been used in China for more than 1,000 years, countries such as South Korea, Japan, North Korea, and Russia are also among the best ecologically suitable areas for ginseng production and potential cultivation [1]. Ginseng is commonly used for its anti-aging, immune-boosting, hypoglycemic, substance-metabolizing, anti-fatigue, and body-function-enhancing functions [2,3], and its anti-aging, anti-fatigue, and anti-hyperglycemic properties are commonly used by humans. These pharmacological effects are thought to result from the chemical constituents of ginseng, such as ginsenosides, polysaccharides, amino acids, flavonoids, and polyphenols [4,5]. Ginsenoside is the most active ingredient in the pharmacological activity of ginseng, and therefore it is also a chemical component that many researchers are enthusiastic about studying [6].

The roots of ginseng are in direct contact with the soil, so the soil is the substrate on which ginseng grows and obtains nutrients, and the quality of soil can affect or even determine the quality of ginseng [7]. From the distribution point of view, soil can be divided into bulk soil and rhizosphere soil. Bulk soil is distant from plant roots and are potential pools of soil nutrients [8]. Rhizosphere soil is in direct contact with plant roots, which is the main place for material exchange and energy flow between plant roots and soil. The carbohydrate secreted by plant roots is the nutrient source of rhizosphere microorganisms, and the enzymes carried by rhizosphere microorganisms can promote the availability of nutrients in rhizosphere soil, thus forming a unique mutually beneficial rhizosphere flora [9,10]. Therefore, the analysis of the characteristics of the rhizosphere zone usually has practical guiding significance.

The physicochemical properties of soil are closely related to the growth of ginseng. Ginseng usually grows in slightly acidic soil environments, with a suitable pH of 5.5-6.5. Both excessively high and low pH are not conducive to the normal growth of ginseng (GB/T 34789-2017). Adequate moisture and breathability are essential conditions for the growth of ginseng, and nutrient management of the soil also needs to be controlled within appropriate ranges [11]. Generally speaking, the application of large amounts of elements (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) is necessary, the application of medium amounts of elements (calcium, magnesium, sulfur) is selective, and the addition of trace elements (zinc, iron, copper, manganese, etc.) usually needs to be limited to a very small range, excessive trace elements can lead to environmental stress [12]. Soil enzymes play an important role in the transformation and transportation of soil nutrients, affecting the mineralization rate of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in the soil, thereby affecting the effective components of nutrient elements in the soil. They are important indicators for evaluating soil fertility [13].

Cultivated perennial plant ginseng usually takes 4-6 years from sowing to harvest, and root disease due to soil factors is a major factor hindering yield and quality [14], therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the soil quality for planting ginseng. Shi et al., [15] reported that ginseng still needs to consume a large amount of A-N and A-P in the soil during the 4-to 6-year-old, the consumption of A-K is relatively low. The consumption of calcium and magnesium in the soil reached a significant level in the second year of ginseng growth, and silicon, iron, manganese, and phosphorus in the soil were mainly consumed in the third year of growth [7,16]. The utilization of soil nutrients by 1-year-old ginseng is not yet clear, and there are no research reports on the specific role of soil properties in the root morphology construction and secondary metabolite accumulation of 1-year-old ginseng. The first year from sowing to growth is a crucial period for ginseng growth, and the first year of ginseng growth is the period of root formation. Improper soil microenvironment can easily lead to the failure of ginseng emergence and rooting. Therefore, the investigation of the rhizosphere soil properties of 1-year-old ginseng is particularly important, this study took the growth of the first year of ginseng sown in different soil microenvironments as the research object, the effects of rhizosphere soil properties on the growth and quality of ginseng were analyzed, and the role of soil properties in the formation of quality differences in one-year-old ginseng was explored.

Materials And Methods

Overview of the experimental site

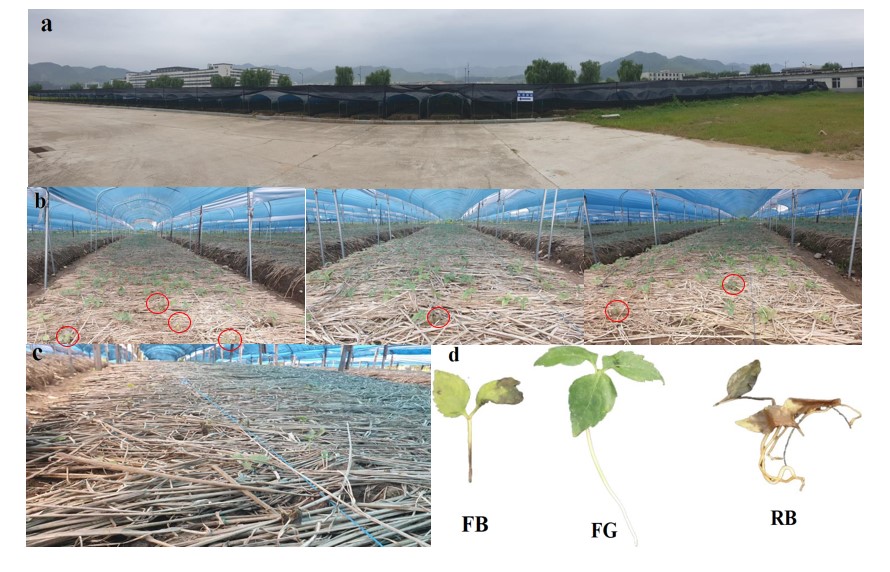

The experiment was carried out at an industrial park of Ji'an Yisheng pharmaceutical in Ji'an city, Jilin province, China (Figure 1a). The site is a continental climate in the north temperate zone with distinct seasons, early spring winds and late autumn frosts. Annual rainfall 800-1000 mm, annual accumulated temperature 3650 °C, frost-free period of 150 days or so, the soil selected for the test was dark brown soil.

Experimental design and sample collection

Two groups of experimental plots were designed. The first group of experimental plots was the farmland with repeated planting of ginseng (35 duplicate plots, each with an area of 2 m × 30 m = 60 m2), which had previously experienced the growth of ginseng for 4 years. The 4-year-old ginseng was harvested in mid September 2023 and the residual roots of ginseng were removed from the soil. The second set of plots were normal cropland after corn had been planted (34 duplicate plots, each with an area of 2 m × 30 m = 60 m2), and before the 2024, all of the cropland had been planted with corn.

The 2024 was sown in two experimental plots in late March. The variety of ginseng seed was “damaya”. Field management practices were carried out with reference to standard methods (GB/T 34789-2017) but with minor modifications. Specifically, shade facilities were set up in the 2024 in April and May (Figure 1a), while, to prevent freezing injury, the soil surface was covered with straw and weeds growing in the field were removed at least twice a month. All the fertilization treatments were not carried out, and we only did irrigation treatments, specifically, watering the soil surface every day before emergence to make the soil surface wet, and used a soil moisture meter to monitor soil moisture and maintain it at 40% -50%; after emergence, in addition to watering the soil surface, we did irrigation treatments, sprayed clear water on the ginseng seedlings until water drops that will not fall from the surface were formed.

On September 1, 2024, ginseng and soil samples were collected. Previous field sampling was generally conducted on 3-6 repeated plots [17,18]. In this study, we randomly selected 6 plots from each treatment group for sample collection. We found that in farmland after planting corn, some ginseng leaves appeared healthy [19], with uniformly dark green and glossy leaves; the leaf veins were clear, and the comparison with the leaf flesh was obvious; the leaves were intact, without any defects or ruptures, and there were no abnormal attachments such as disease spots, powdery substances, water stains, rust spots, etc; the leaves were flat and the edges are natural, we abbreviated these ginseng as FG (Figures 1b & d). Other ginsengs had unhealthy purplish-brown, yellow-green and tan leaves (Figures 1b & d), which we abbreviated to FB. In fields where ginseng was replanted, almost all of the ginseng leaves showed an unhealthy appearance (Figures 1c & d), but fortunately the roots were still present, and we abbreviated these samples to RB. For each treatment, we collected FG, FB, and RB, approximately 15-20 roots of each ginseng species per ginseng field. For rhizosphere soil, we referred to a previous method [20] to collect soil adhering to the roots of ginseng using the root-shaking method and mixed the soil collected in each ginseng field as a set of replicates.

Separated the ginseng from the soil and placed it in a sterile self-sealing bag. Put them in a freezer with an ice pack and took them back to the laboratory. After washing the soil on the root surface of ginseng with deionized water, the agronomic traits of ginseng were photographed and recorded, and then dried. The dried ginseng was used for the analysis of ginsenoside content. When dealing with soil samples, the soil was first homogenized and then equally divided into two parts, one part was naturally air-dried and the other part was placed in a 4°C refrigerator for cryopreservation.

Figure 1: Overview of the study area (a) and sampling (b-d).

Determination of agronomic characters of ginseng roots

The root length of ginseng was determined by ruler (Ningbo Deli Tool Co., Ltd.), and the rhizome length and root diameter of ginseng were determined by Vernier Caliper (DL91150 type, Ningbo Deli Tool Co., Ltd., accurate to 0.01 mm). The fresh weight and dry weight (air-dried) of ginseng roots were measured by an electronic balance (ME204, Mettler Toledo Instrument Co., Ltd.), and the drying rate (dry weight/fresh weight × 100%) was calculated.

Determination of ginsenoside content

Took the dried ginseng root from “2.2” and ground it with a grinder and passed through a 0.18 mm sieve. The content of ginsenoside Rg1, Re, Ro, Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rf, Rc, Rd, (R-type) Rg3, and (R-type) Rh2 was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography according to a previous report [20]. Specifically, Thermo Ultimate 3000 high-performance liquid chromatography was used with an Elite Hypersil ODS2 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) column. Mobile phase, flow rate, column temperature, detection wavelength and injection volume were presented in table S1. The determination of total ginsenosides (TG) was performed according to standard methods (GB/T 18765-2015). Each sample was determined in 3 replicates, and the average value was taken as the final result.

Determination of soil physicochemical properties

The more physical, chemical and biological indicators are used for soil quality evaluation, the more accurate the soil quality evaluation is. It is an important part of soil quality evaluation to select indicators that are closely related to soil quality and relatively independent. In this study, for soil physical properties, we determined soil Bulk Density (BD) and Field Water Capacity (FWC) using the ring knife method and soil Mass Water Content (MWC) using the oven drying method. According to the reference standard method (LY/T1225-1999), the classification of soil aggregates (AGG) was determined using manual dry screening method. The specific method was as follows: sieve holes with diameters of 3.0 mm, 2.00 mm, 1.00 mm, 0.85 mm, 0.5 mm, and 0.25 mm from top to bottom, placed them on the bottom of the sieve, weighed about 100 g of air dried soil and place it on the 3 mm sieve, and covered it with a manual sieve to divide the soil into 7 particle size groups, namely AGG > 3 mm, 2-3 mm, 1-2 mm, 1-0.85 mm, 0.85-0.5 mm, and 0-0.25 mm. The screened aggregates of each particle size were accurately weighed and the mass percentage of each particle size was calculated.

For soil chemical properties, pH and conductivity (EC) were measured using a pH meter and conductivity meter under a soil to water ratio of 1:5. The alkaline hydrolysis diffusion method was used to determine the Alkaline hydrolysis Nitrogen (A-N), and the 1 mol/L ammonium acetate extraction-flame photometry method was used to determine the available potassium (A-K). The determination of phosphorus components referred to the grading method of Chang and Jackson and Olsen [21,22]. Specifically, the molybdenum antimony colorimetric method was used to determine the available phosphorus in soil. The leaching agents used for calcium bound Phosphorus (Ca-P), iron bound Phosphorus (Fe-P), Aluminum bound Phosphorus (Al-P), occluded phosphorus (O-P), available phosphorus (A-P), and inorganic phosphorus (I-P) were 0.5 mol/L H2SO4 solution, 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution, 0.5 mol/L ammonium fluoride solution, three acid mixtures (H2SO4: HClO: HNO3=1:2:7) digestion, 0.5 mol/L NaHCO3 solution, and 1 mol/L HCl solution, respectively. Organic carbon (SOC) was determined using an elemental analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar, Hanau, Germany), while easily Oxidizable Organic Carbon (EOC) was determined using a 333 mmol/L potassium permanganate solution oxidation method. The Exchangeable Total Acid (E-TA), exchangeable hydrogen ion (E-H+), and Exchangeable Aluminum Ion (E-Al3+) were determined by leaching with 1mol/L KCl and titration with 0.02 mol/L NaOH solution. Boiling water extraction-curcumin colorimetric method for determining available boron (A-B), calcium dihydrogen phosphate extraction-BaSO4 turbidimetric method for determining available sulfur (A-S), 0.025 mol/L citric acid solution extraction-silicon molybdenum blue colorimetric method for determining Available Silicon (A-Si), phenol disulfonic acid colorimetric method for determining nitrate nitrogen (NO3--N), KCl extraction-indophenol blue colorimetric method for determining ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N), sodium pyrophosphate extraction-phenanthroline colorimetric method for determining complexed iron (C-Fe), pure water extraction-titration method for determining calcium ions (Ca2+), magnesium ions (Mg2+), chloride ions (Cl-), sulfate ions (SO42-) and bicarbonate ion (HCO3-). The determination of cation exchange capacity (CEC) was referred to the “National Environmental Protection Standards of the People's Republic of China” (HJ 889-2017). The reducing sugar content in soil was determined using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetric method [23], the total sugar content was determined using the phenol-concentrated sulfuric acid method [24], and the protein content was determined using the Bradford method. The specific measurement methods were presented in Bao and Lu [25,26].

In order to better define the potential nutrient supply capacity in the soil, this study also determined the content of total elements in the soil, in which the content of total boron (T-B) was determined according to GB/T 3653.1-2024, the content of total manganese (T-Mn), total titanium (T-Ti), total calcium (T-Ca), total magnesium (T-Mg), total iron (T-Fe), total aluminum (T-Al), and total silicon (T-Si) was determined according to HJ 974-2018. The content of total zinc (T-Zn) was determined according to HJ 491-2019, and the determination of total europium (T-Eu), total lanthanum (T-La), total cerium (T-Ce), total praseodymium (T-Pr), total neodymium (T-Nd), total samarium (T-Sm), total gadolinium (T-Gd), total terbium (T-Tb), total dysprosium (T-Dy), total holmium (T-Ho), total erbium (T-Er), total thulium (T-Tm), total ytterbium (T-Yb), total lutetium (T-Lu), and total yttrium (T-Y) content referred to GB/T 18115.6-2023.

Determination of soil enzyme activity

The activities of some soil enzymes, including dehydrogenase (DHA, Cat: BC0390), phytase (Phy, Cat: BC5370), arylsulfatase (ASF, Cat: BC3995), uricase (UR, Cat: BC4410), polyphenol oxidase (PPO, Cat: BC0110), peroxidase (POD, Cat: BC0890), ascorbate peroxidase (APX, Cat: BC0220), lacase (LAC, Cat: BC1960), L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL, Cat: BC0210), fluorescein diacetate hydrolase (FDA, Cat: BC0485), hydroxylamine reductase (HR, Cat: BC3010), β-glucosidase (β-Glu, Cat: BC0160), α-glucosidase (α-Glu, Cat: BC2550), superoxide dismutase (SOD, Cat: BC5160), glutaminase (GLS, Cat: BC3970), asparaginase (ASP, Cat: BC1600), were determined using the kit of Beijing Solabao Technology Co., Ltd.

The activity of amylase (AMY), α-amylase (α-AMY), β-amylase (β-AMY), cellulase (Cel), and invertase (Inv) was determined using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetric method. The activity of acid phosphatase (ACP) was determined using the sodium phenylphosphate colorimetric method, the activity of nitrate reductase (NR) was determined using the phenol disulfonic acid colorimetric method, the activity of catalase (CAT) was determined using the potassium permanganate titration method, and the activity of ribonuclease (NUC) was determined using GB/T 34222-2017. The activity of urease (Ure) was determined using the phenol sodium hypochlorite colorimetric method, and the activity of protease (Prot) was determined using the ninhydrin colorimetric method. The specific measurement methods were presented in Guan.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Measured all indicators three times and took the average as the final result. Used Microsoft Excel 2020 to organize the data, and then analyzed the data using SPSS 26.0 software. Firstly, performed Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan's multiple range test on data that conforms to normal distribution. Performed Dunnett's T3 test on data that did not conform to normal distribution, with p < 0.05 as the criterion for significant differences. The correlation analysis based on Spearman and Pearson test was also conducted in SPSS 26.0 software, then FDR correction was applied to the initial calculated p-value, and the difference was considered statistically significant when the adjusted p-value was less than 0.05. Performed random forest analysis using R (version 4.1.3) and the "randomForest" package (versions 4.7-1.1), and visualized it in the ggplot2 package (version 3.4.0). Performed principal component analysis (PCA) using the vegan package (v3.6.1) in R (v4.1.3), and visualized in the ggplot2 package (v3.3.3). The visualization of data and analysis results was performed in GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 and SigmaPlot 10.0.

Results

Agronomic traits and ginsenoside content of ginseng

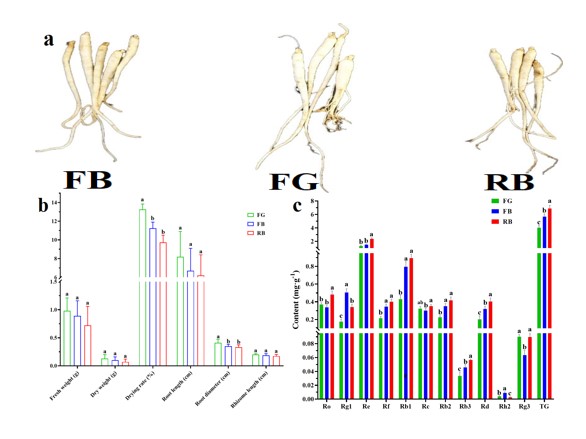

From the appearance (Figure 2a), FG was whiter and no lesions were present. The color of FB was darker. Although the color of RB was not obviously different from that of FB, there were some lesions in the root. Among the agronomic traits (Figure 2b), FG had higher root fresh weight (0.98 g), dry weight (0.13 g), and drying rate (13.27%) than FB (0.89 g; 0.1 g; 11.24%) and RB (0.72 g; 0.07 g; 9.72%), although only the drying rate differed significantly (p < 0.05). In addition, the root length (8.2 cm) and rhizome length (2.02 mm) of FG were also higher than those of FB (6.7 cm; 1.87 mm) and RB (6.2 cm; 1.74mm) , but the difference was not significant (p > 0.05). Notably, the root diameter of FG (0.41 cm) was significantly larger than that of FB (0.35 cm) and RB (0.33 mm, p < 0.05).

The content of ginsenosides Ro, Re, Rf, Rb1, Rc, Rb3, Rd, and TG in RB were higher than those in FG and FB, the content of Ro, Re, Rb3, Rd, and TG were significantly different from those of FG and FB (p < 0.05). The TG content of RB (6.91 mg/g) was 1.72 and 1.22 times that of FG (4.02 mg/g) and FB (5.68 mg/g), respectively. The content of ginsenoside Rg1 and Rh2 in FB were significantly higher than those in FG and RB, and only the content of ginsenoside Rg3 in FG was higher than that in the other two treatments, but the difference with RB was not significant (p > 0.05).

Figure 2: Appearance (a), agronomic traits (b), and content of ginsenosides (c) of ginseng.

Figure 2: Appearance (a), agronomic traits (b), and content of ginsenosides (c) of ginseng.

Soil physicochemical properties

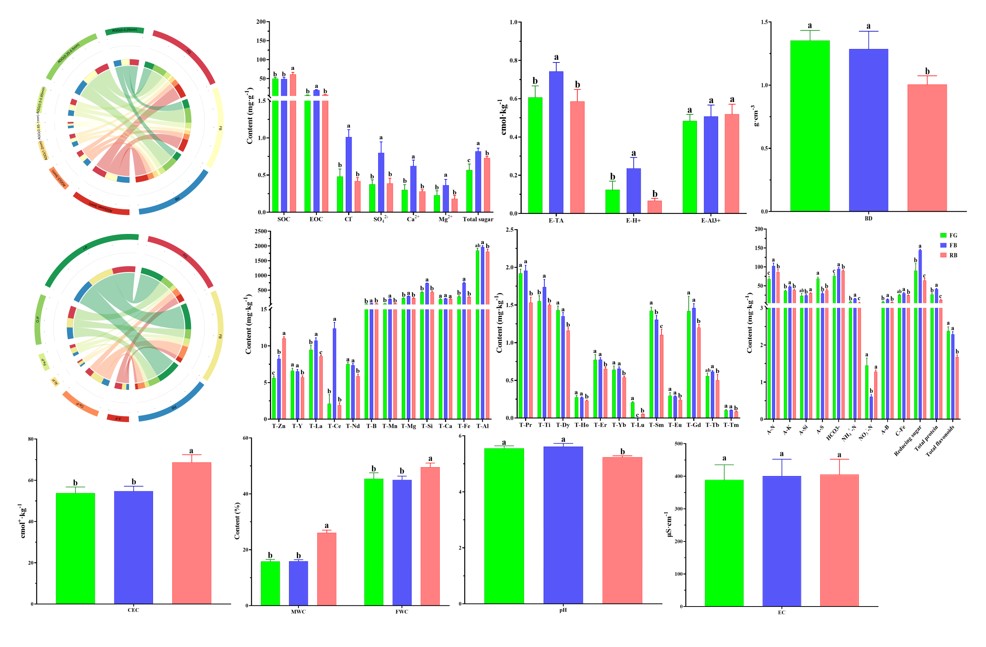

Among the soil physical properties (Figure 3), FG had higher content of AGG (0-0.25 mm) and AGG (> 3 mm), FB had higher content of AGG (0.25-0.85 mm), and RB had higher content of AGG (0.85-3 mm) than FG and FB, respectively, however, the difference between them did not reach significant level (p > 0.05). The BD of FG and FB was significantly higher than that of RB, while the MWC and FWC of RB were significantly higher than those of FG and FB (p < 0.05).

Of the total soil elements (Figure 3), FB had the greatest potential nutrient supply capacity, specifically, FB had higher level of T-La, T-Ce, T-Mn, T-B, T-Mg, T-Si, T-Fe, T-Al, T-Pr, T-Ti, T-Yb, T-Gd, and T-Tb than FG and RB, although some differences were not significant. The potential nutrient supply capacity of FG was second only to FB, and T-Y, T-Nd, T-Dy, T-Ho, T-Er, T-Lu, T-SM, T-Eu, and T-Tm were higher in FG than in the other groups. The potential nutrient supplying capacity of RB was the lowest, only the content of T-Zn in RB was significantly higher than that in FG and FB (p < 0.05).

In other soil chemical property (Figure 3), RB had the highest content of SOC, A-Si, and CEC, FG had the highest content of A-S and NO3--N, and FG had the highest content of total flavonoids, A-P, and O-P. The vast majority of indicators in FB (EOC, NH4+-N, A-N, A-K, A-B, C-Fe, pH, Ca-P, Al-P, Fe-P, I-P, etc.) were the highest in all groups, which indicated that FB had the highest available nutrient content in addition to the highest potential nutrient supply capacity.

Figure 3: Physicochemical properties of different soil samples.

Figure 3: Physicochemical properties of different soil samples.

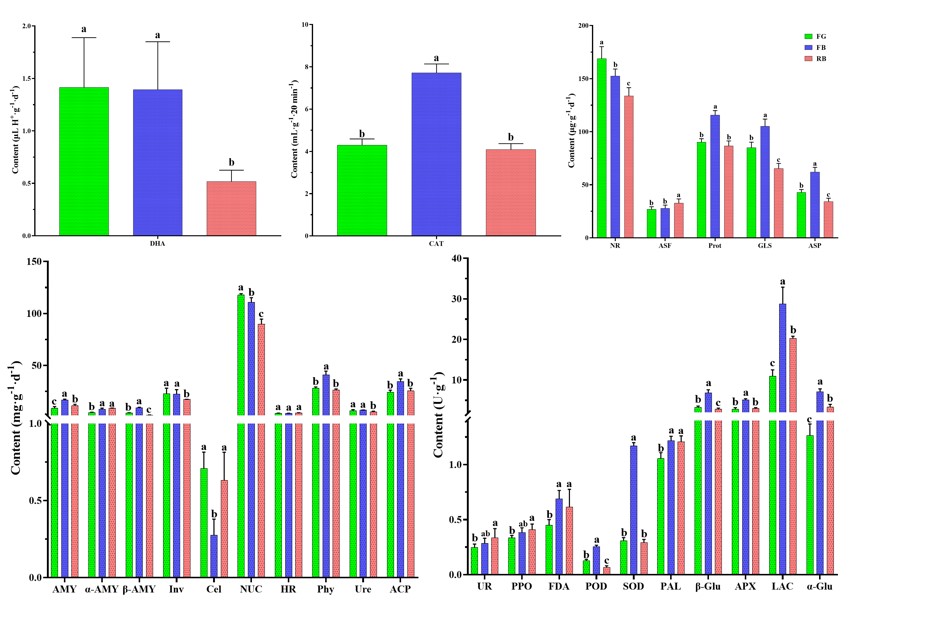

Soil enzyme activity

Among soil enzyme activities (Figure 4), we found that FB not only had the greatest nutrient supply capacity, but also had the greatest enzyme activity, similar to soil physicochemical properties. Specifically, the activities of CAT, Prot, GLS, ASP, AMY, α-AMY, β-AMY, HR, Phy, ACP, FDA, POD, SOD, PAL, β-Glu, APX, LAC, and α-Glu of FB were higher than those of other groups. The enzyme activity of FG was second only to that of FB, and the activities of DHA, NR, Inv, Cel, NUC and Ure were higher in FG, although many were not significantly different (p < 0.05). In RB, only ASF, UR, and PPO showed higher activity than the other groups.

Figure 4: Enzyme activity of different soil samples.

Figure 4: Enzyme activity of different soil samples.

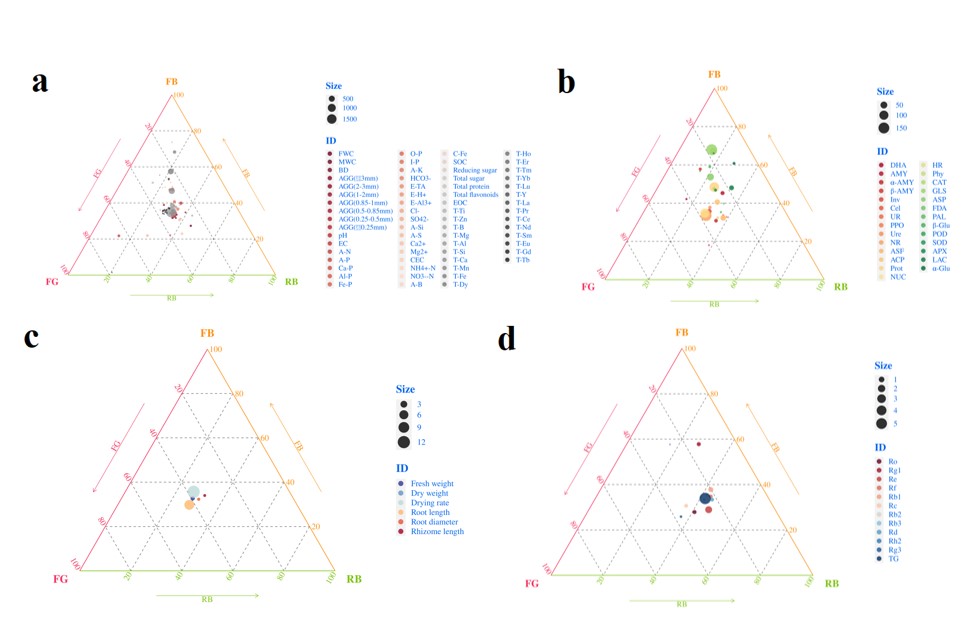

Ternary plot analysis

In order to clarify the differences between different soil and ginseng samples, a ternary plot analysis was conducted (Figure 5). In terms of soil physicochemical properties, more soil nutrients were enriched in FB (Figure 5a); in terms of soil enzyme activity, higher enzyme activity was also enriched in FB (Figure 5b). FG was enriched with higher abundance of agronomic traits (Figure 5c), while RB was enriched with more ginsenoside content (Figure 5d).

Figure 5: Ternary plot displaying the abundance of indicators for different soil and ginseng samples. (a) Soil physicochemical properties; (b) Soil enzyme activity; (c) Agronomic traits of ginseng; (d) Content of ginsenosides.

Figure 5: Ternary plot displaying the abundance of indicators for different soil and ginseng samples. (a) Soil physicochemical properties; (b) Soil enzyme activity; (c) Agronomic traits of ginseng; (d) Content of ginsenosides.

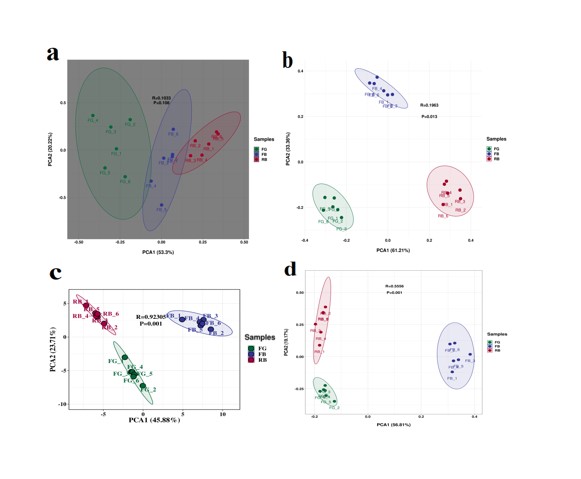

Principal component analysis

To clarify the differences in soil properties and ginseng quality, we performed Principal Component Analysis (PCA). In the PCA of agronomic traits (Figure 6a), although the three groups of ginseng did not appear to be well differentiated (p > 0.05), however, it can be roughly inferred that there are significant differences between RB and FG. In the PCA of ginsenoside content (Figure 6b), there were significant differences among the three groups (p =0.013).

In the PCA of soil physicochemical properties (Figure 6c), although the three groups were significantly separated (p =0.001), the similarity between FG and RB was higher, this may be due to the fact that FG and Rb were in a lower state of availability and potential nutrient content relative to FB. The PCA results of soil enzyme activities were similar to the physicochemical properties (Figure 6d), and the similarity between RB and FG was higher under the premise of significant separation of the three groups (p =0.001).

Figure 6: Principal component analysis. (a) Agronomic traits of ginseng; (b) Ginsenoside content of ginseng; (c) Soil physicochemical properties; (d) Soil enzyme activity.

Figure 6: Principal component analysis. (a) Agronomic traits of ginseng; (b) Ginsenoside content of ginseng; (c) Soil physicochemical properties; (d) Soil enzyme activity.

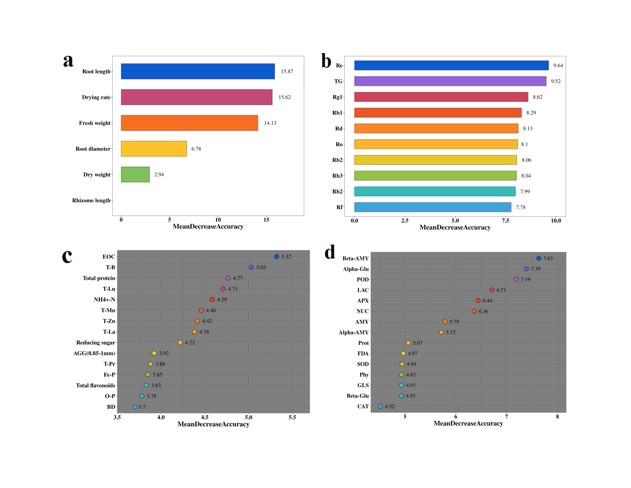

Random forest analysis

The results of PCA had established that there were significant differences between the three groups, but the characteristic factors responsible for these differences were not yet clear. Here, we used random forest analysis to identify the signature factors underlying these differences (Figure 7). Among the agronomic traits of ginseng (Figure 7a), root length, drying rate, and fresh weight were the characteristic factors of differences. In the content of ginsenosides (Figure 7b), ginsenoside Re, TG, and Rg1 were the characteristic factors of differences. In soil physicochemical properties (Figure 7c), EOC, T-B, and total protein were the characteristic factors of differences. In soil enzyme activity, β-AMY, α-Glu, and POD were the characteristic factors of differences (Figure 7d).

Figure 7: Random forest analysis. (a) Agronomic traits of ginseng; (b) Ginsenoside content of ginseng; (c) Soil physicochemical properties; (d) Soil enzyme activity.

Figure 7: Random forest analysis. (a) Agronomic traits of ginseng; (b) Ginsenoside content of ginseng; (c) Soil physicochemical properties; (d) Soil enzyme activity.

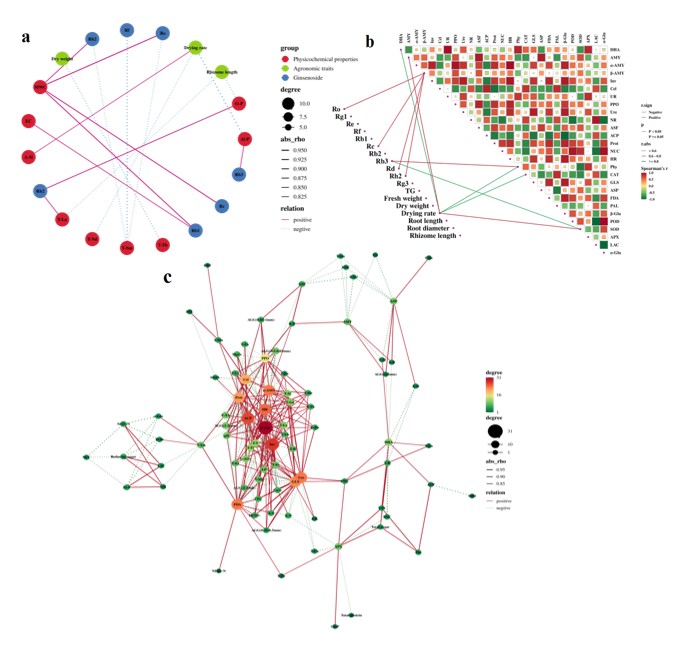

Correlation Analysis

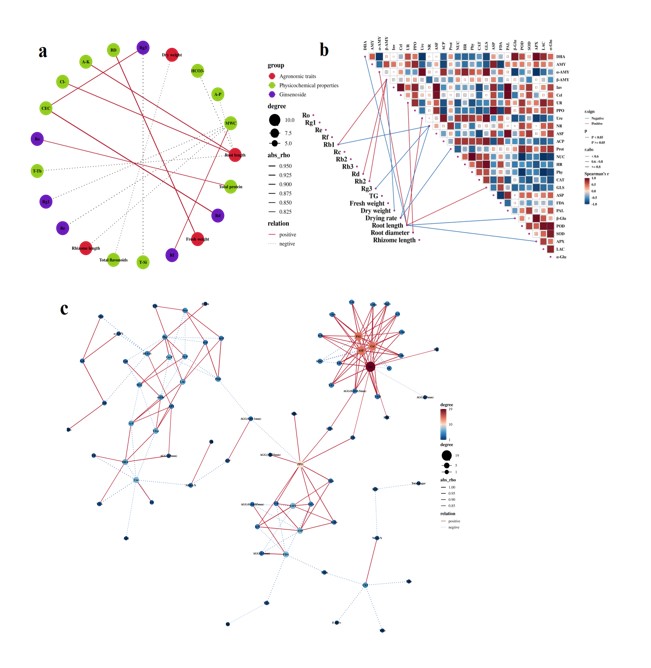

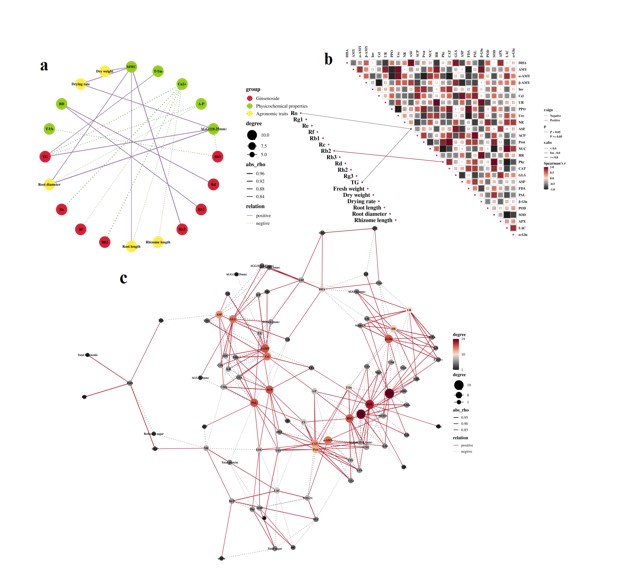

To clarify the potential influence of soil factors in ginseng agronomic traits and ginsenoside content, we performed a correlation analysis of ginseng quality indicators and soil properties based on Spearman test (Figures 8-10).

Correlation analysis of factors in FG: In the correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (Figure 8a & Table S2), MWC was significantly positively correlated with ginsenosides Rh2, Ro, Rc, and Rb1, and T-Sm was significantly negatively correlated with ginsenosides Rh2, Ro, and Rf, T-Lu was significantly correlated with ginsenoside Rb2 and rhizome length, Al-P was significantly correlated with ginsenoside Rb3 and drying rate (p < 0.05) . In addition, T-Tb, T-Nd and other soil factors were also significantly correlated with the quality indicators of ginseng.

In the correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil enzyme activities (Figure 8b), β-AMY was significantly positively correlated with ginsenoside Ro, Rc, Rd, and Rh2, Phy and SOD were significantly correlated with ginsenoside Rb3 and drying rate (p < 0.05). In addition, DHA, AMY, and CAT were also significantly correlated with the quality indicators of ginseng.

In the correlation analysis of soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities (Figure 8c & Table S2), β-Glu, ACP, and Inv were the core nodes in the correlation network of soil physicochemical properties, the correlation network between soil physicochemical properties and HR, α-AMY, FDA, GLS, Ure also had a greater impact.

Figure 8: Correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (a), enzyme activity (b), and the correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity (c) in FG.

Figure 8: Correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (a), enzyme activity (b), and the correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity (c) in FG.

Correlation analysis of factors in FB: In the correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (Figure 9a & Table S3), MWC was significantly correlated with ginsenoside Rg1, Re, Rf and rhizome length, and CEC was significantly positively correlated with ginsenoside Rg3 and Rd (p < 0.05). In addition, BD, T-Si, and T-Tb were also significantly correlated with the quality indicators of ginseng.

In the correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil enzyme activities (Figure 9b), β-AMY was significantly correlated with ginsenoside Rb1, Rd, Rg2, and dry weight, NR was significantly correlated with ginsenoside Rb1, Rg3, and drying rate (p < 0.05). In addition, DHA, α-AMY, and β-Glu were also significantly correlated with the quality indicators of ginseng.

In the correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities (Figure 9c & Table S3), Inv, ASF, Cel, and PAL were the core nodes in the correlation network of soil physicochemical properties.

Figure 9: Correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (a), enzyme activity (b), and the correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity (c) in FB.

Figure 9: Correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (a), enzyme activity (b), and the correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity (c) in FB.

Correlation analysis of factors in RB: In the correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (Figure 10a & Table S4), MWC was significantly positively correlated with dry weight, drying rate, root diameter, root length, and ginsenoside Rb3. Ca2+ was negatively correlated with root length, rhizome length, ginsenoside Ro, Rf, Rh2, and TG, while AGG (0-0.25 mm) was positively correlated with drying rate, root diameter, and TG (p < 0.05) . In addition, BD, A-P, and T-Yb were also significantly correlated with the quality indicators of ginseng.

In the correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and enzyme activities (Figure 10b), ASF was significantly negatively correlated with ginsenoside Ro and TG, and Phy was significantly positively correlated with ginsenoside Rb2 (p < 0.05).

In the correlation analysis of soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities (Figure 10c & Table S4), AMY, Ure, and FDA were the core nodes in the correlation network of soil physicochemical properties, α-AMY, β-AMY, β-Glu, PPO, ACP, PAL and soil physicochemical properties also had a greater impact on the correlation network.

Figure 10: Correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (a), enzyme activity (b), and the correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity (c) in RB.

Figure 10: Correlation analysis between ginseng quality indicators and soil physicochemical properties (a), enzyme activity (b), and the correlation analysis between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity (c) in RB.

Discussion

Quality indicators of ginseng

Appearance traits are one of the main indicators for the quality evaluation of traditional Chinese medicinal materials, and roots are the most commercially important product of ginseng, with white to beige, smooth surface without blemishes being considered a must for top grade ginseng [27]. In this study, it is clear that the root of FG have the best appearance, although not for commercial purposes. Since we did not fertilize the ginseng, and in the same experimental area, climatic conditions were not the most important factor for the difference in quality between FG and FB, RB, instead, the soil factor was the most important factor for the quality difference of the 3 groups of ginseng, which makes our study meaningful.

Ginsenoside is the most active ingredient in the pharmacological activity of ginseng, and the content of ginsenoside has been included in the evaluation index of ginseng quality in China, the United States, and the European Union [28]. Taken together, the pharmacological value of RB appeared to be higher in this study, as RB has significantly higher contents of ginsenosides Ro, Re, Rb3, Rd and TG (Figure 2c). On the contrary, FG, which had the most perfect appearance, only had the higher content of ginsenoside Rg3. As ginsenosides are the secondary metabolites of ginseng, and secondary metabolites are the products of environmental stress and the unique material basis for plant adaptation to environmental stress [21,29]. The content of secondary metabolites is relatively low when plants are growing in a good environment, while the content of secondary metabolites is increased when plants are growing in adversity, which is used to resist and adapt to adversity stress. Like primary metabolites, secondary metabolite synthesis consumes a large amount of photosynthetic products and energy, and therefore, as a price, when secondary metabolites accumulate, the primary metabolites of plants are correspondingly reduced, this in turn leads to impaired vegetative growth and reduced yield [30,31]. Continuous cultivation of ginseng on the same plot is prone to replant disease [32], which leads to disease in the milder cases and death in the more severe cases. Replant disease of ginseng is associated with soil acidification, salinization, uneven nutrient structure, and increased relative abundance of pathogenic bacteria [33]. We speculate that the performance of RB in appearance traits and ginsenoside content in this study is caused by the deterioration of the soil microenvironment, while FB and FG had better appearance characters because they grow in better environment, and their ginsenoside content is lower than RB.

Relationship between soil physicochemical properties and ginseng quality

Inappropriate soil physicochemical properties are the main manifestation of plant abiotic stress at the soil level, such as water stress [34], drought stress [35], salt stress [36], heavy metal [37,38]. The results of this study reveals that low levels of available and potential nutrients are the main characteristics of RB, which may be related to continuous cultivation of ginseng; while higher available and potential nutrients are the main characteristics of FB. For FG, the available and potential nutrients were roughly between FB and RB (Figure 3). This may reflect the fact that ginseng seed germination and first-year growth, over-nutrition and under-nutrition cropping patterns are not optimal for ginseng growth. The substance stored in the seed is the energy source for seed dormancy and germination, and the root system of ginseng in the first year of growth is not fully developed, nutrients in the soil may not be well taken up by ginseng roots less than one year old [39,40], therefore, one-year-old ginseng with high morphology and ginsenoside content can not be cultivated with high nutrient content.

Although soil nutrient content was not the principal factor affecting the quality of 1-year-old ginseng, according to the results of correlation analysis, we found that soil water content was the essential factor affecting the quality of 1-year-old ginseng, this was consistently validated across the 3 groups (Figures 8a, 9a & 10a). Water is the basis of all physiological and biochemical activities in plants. Meeting the balance between supply and demand of water metabolism in the growth and development of ginseng is one of the prerequisites to ensure high quality and yield of ginseng. When the water content is suitable, the fibrous roots of ginseng grow vigorously, the cells of roots, stems and leaves expand, the water content in the vacuole is rich, and ginseng grows well; if the water content drops suddenly, the state of enzymes in the cells will be changed, and the strength and direction of metabolic processes catalyzed by enzymes [41,42]. Our findings were consistent with those reported by Hei et al., [43], Lee and Mudge [44], in addition, in our previous study, we reported a significant correlation between soil factors (A-P, ACP, pH, Cel, and BD) and the accumulation of ginsenosides in 3-year-old field ginseng [7], while Cel, Ure, NO3--N, and MWC showed a significant correlation with the content of ginsenosides in 2-, 3-, and 4-year-old ginseng at harvest time [20]. This indicates that the soil factors that affect the accumulation of ginsenosides in ginseng at different ages may not be identical for ginseng of different ages. In future research, it is necessary to delve into the specific role of moisture content in 1-year-old ginseng, and investigate the specific effects of appropriate moisture content, high and low levels of moisture content, on ginseng. The field management measures for ginseng cultivation specified in GB/T 34789-2017 are currently the latest version in China and widely used by farmers. However, these standards do not specify how much water should be provided for ginseng growth at different stages. Our suggestion is to refine this standard by distinguishing the water requirements of ginseng at different ages based on their age.

Ca2+ has been previously reported as a well-known signaling molecule with a role in mediating the production of ginsenosides [45]. At the same time, an appropriate amount of calcium is necessary to promote ginseng root growth [46], and it is essential for root growth, but we only see a significant effect of Ca2+ in RB. It has been reported that different macronutrients (N, P, and K) supply may lead to different uptake and utilization of medium elements (Ca, Mg, and S) and micronutrient (B, Zn, Mn, etc.) by plants, for example, Zhou et al., [47] reported that nitrogen addition significantly affected Allium fistulosum L. uptake of micronutrient (Ca, Mn, Cu, and Zn) and soil N supply were significantly negatively correlated with Mg and significantly positively correlated with Fe, Cu, and Zn in Saposhnikovia divaricata [48]. Soil P content can affect plant tissue-specific allocation of P and nitrogen metabolism in vivo [49], and plants tend to form thinner and longer roots under low P supply [50]. In addition to being directly involved in stem toughness and root yield in plants, potassium has also been implicated in water management and carbohydrate (sugar, starch, cellulose) synthesis in roots [51]. Therefore, we speculate that this may be due to the specific soil environment of RB, where the supply of large elements (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) in the soil does not meet the standards required for ginseng growth. Ginseng tends to absorb the medium element Ca, and the expansion of the root system is closely related to calcium [46]. During the formation of 1-year-old ginseng from seeds to roots, Ca can only be obtained from the soil. Whether the role of Ca can replace nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in 1-year-old ginseng is a topic worthy of further research.

In this study, we also found that rare earth elements (La, Nd, Sm, Tb, Yb, Tm) were more significantly associated with ginseng quality indicators than major elements, it is suggested that rare earth elements may have some specific effects on the quality formation of one-year-old ginseng, and Tb was related to the agronomic traits of ginseng in FG and FB. In the study of soil nutrients, scholars often focus on the role of macroelements in the formation of ginseng quality, such as nitrogen [52], phosphorus [53], potassium [54], calcium [44], iron [29]. As far as we know, the research on the effect of rare earth elements on ginseng quality formation is almost completely blank, which is extremely challenging.

Relationship between soil enzyme activities and ginseng quality

Soil enzymes are bioactive proteins in soil and biocatalysts in ecosystem. Soil enzymes are involved in nutrient cycling and energy flow, and soil enzyme activities are considerable indicators for evaluating soil fertility [13]. In this study, the activities of most of the enzymes of FB were higher than those of FG and RB (Figure 4), which may be the reason why FB have the highest available and potential nutrient content. It is well known that enzymes are significantly correlated with nutrient supply capacity [55]. For example, FB had significantly higher activities of nitrogen- (Prot, GLS, and ASP) and carbon- (AMY, α-AMY, β-AMY, and Inv) cycle related enzymes, which contributed to significantly higher A-N and EOC contents in FB [56]; the content of A-S in FG was significantly higher than that in the other two treatments due to the higher ASF activity.

Soil enzymes stimulate the decomposition and transformation of organic matter and the activation and release of available nutrients, playing a role in promoting the accumulation of active ingredients in ginseng indirectly [57]. At the same time, microorganisms containing soil enzymes can also directly stimulate the accumulation of ginsenosides, such as the potential ginseng pathogenic genera Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Nectria, which were reported to have the ability to directly produce ginsenosides [3]. Enzymes produced by microorganisms (β-Glu, uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferase, β-galactosidase, β-xylosidase, cellulase, etc.) are also necessary catalysts for the production and structural transformation of ginsenosides [58,59]. In this study, β-AMY showed a strong association with ginseng quality in both FG and FB (Figures 8b & 9b), while β-AMY was also a characteristic factor for differences in enzyme activity between different soil samples (Figure 7d). According to reports, AMY mainly acts on starch to cut the α-1,4-glycosidic bond and β-1,6-glycosidic bond from the non-reducing end in turn, producing maltose, glucose, maltodextrin, maltooligosaccharides, to provide an available carbon source for the soil [60,61]. However, according to the results of correlation analysis, no significant association was found between soil available carbon (EOC) and ginsenosides (Figures 8a, 9a & 10a), whereas EOC was a characteristic factor for differences in soil abiotic factors (Figures 7c), this may be because we haven't fertilized the soil for a year, and microorganisms need to break down the bound carbon in the soil into free carbon to meet their own nutritional needs. In the correlation network between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities (Figures 8c, 9c & 10c), the core nodes were all related to nutrient cycling enzymes (mainly carbon cycle), which also proved this point. Thus, we suspect that it may be the microbial host that produces enzymes (β-AMY, NR, Phy, etc.) that directly influence the greater likelihood of ginsenoside accumulation rather than changes in available carbon (EOC) content. Among the AMY-producing microorganisms, Bacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus were highlighted, such as Bifidobacterium vaginale, Bifidobacterium lacrimalis, Bacillus licheniformis, L. Crispatus, L. Jensenii, L. Iners, L. Gasseri [62,63]. While these microorganisms are usually present in plants and are commonly referred to as endophytic microorganisms [64,65]. Therefore, we speculate that the strong association between β-AMY and ginsenosides is due to the infiltration of microorganisms such as Lactobacillus and Bacillus into ginseng roots to help accumulate. The prominent role of the microbial host Lactobacillus in the production of ginsenosides has been demonstrated [3]. Due to our focus on the potential role of soil abiotic factors in this study, the role of soil biotic factors in the quality formation of 1-year-old ginseng is not the main focus of this research. However, this does not affect our exploration of the interaction between AMY producing microbial hosts and ginseng in future experiments. In addition, further research should focus more on the study of the microbiome, analyzing the results of the microbiome as a whole with soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity to verify the results of this report and provide sufficient basis for better understanding the growth dynamics of 1-year-old ginseng and its response to soil microecology.

Conclusion

This study conducted a difference and association analysis of the quality indicators of 1-year-old ginseng in different soil environments and the soil factors of the rhizosphere soil microenvironment in which it was grown. The results indicate that ginseng grown in different soil environments have different morphological characteristics and ginsenoside content, which is closely related to the soil environment. Among them, compared with the nutrient content in the soil, the role of soil moisture in the quality formation of 1-year-old ginseng had been consistently supported by the analysis results. We also found that rare earth elements (Sm, La, Tb, Nd) played a dominant role in the formation of ginseng quality in normally growing ginseng (FG), while in soil environments with higher and lower nutrients, rare earth elements played a more dominant role in the formation of ginseng quality, the quality formation of ginseng was more dependent on macroelements (P, Si, Ca). Finally, we found that microbial hosts dominated by β-AMY production may play a principal role in nutrient cycling in rhizosphere microecology, which affected ginseng quality to a greater extent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable. The plant was collected in non-protected area; no any legal authorization/license is required.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Author’s Contribution

Zhefeng Xu: Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Visualization. Yuqiu Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology. Jiahong Sui: Formal analysis. Kemeng Zhang and Yan Xue: Writing-review & editing. Yibing Wang and Jing Fang: Visualization, Investigation. Ye Qiu, Tao Zhang, and Changbao Chen: Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan Project (No. 20250101032JJ), the National Key R&D projects of China (2024YFC3506800), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Foundation Program (No. 82204556).

Supplementary Tables

References

- Jung J, Kim KH, Yang K, Bang KH, Yang TJ (2014) Practical application of DNA markers for high-throughput authentication of Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius from commercial ginseng products. J Ginseng Res 38: 123-129.

- Choi KT (2008) Botanical characteristics, pharmacological effects and medicinal components of Korean Panax ginseng C A Meyer. Acta Pharmacol Sin 29: 1109-1118.

- Chu LL, Huy NQ, Tung NH (2023) Microorganisms for Ginsenosides Biosynthesis: Recent Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. Molecules 28: 1437.

- Liu Y, Zhang H, Dai X, Zhu R, Chen B, et al. (2021) A comprehensive review on the phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics, and antidiabetic effect of Ginseng. Phytomedicine 92: 153717.

- Ratan ZA, Haidere MF, Hong YH, Park SH, Lee JO, et al. (2021) Pharmacological potential of ginseng and its major component ginsenosides. J Ginseng Res 45: 199-210.

- Liu S, Wang Z, Niu J, Dang K, Zhang S, et al. (2021) Changes in physicochemical properties, enzymatic activities, and the microbial community of soil significantly influence the continuous cropping of Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng). Plant Soil 463: 427-446.

- Xu Z, Chen Y, Liu R, Wang Y, Liu C, et al, (2025) Effect of rhizosphere soil microenvironment interaction on ginsenoside content in Panax ginseng: a case study of three-year-old agricultural ginseng. Rhizosphere 33: 101023.

- Zhalnina K, Louie KB, Hao Z, Mansoori N, Rocha UN, et al. (2018) Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly. Nat Microbiol 3: 470-480.

- Ferjani R, Marasco R, Rolli E, Cherif H, Cherif A, et al. (2015) The date palm tree rhizosphere is a niche for plant growth promoting bacteria in the oasis ecosystem. Biomed Res Int 2015: 153851.

- Timm CM, Carter KR, Carrell AA, Jun SR, Jawdy SS, et al. (2018) Abiotic Stresses Shift Belowground Populus-Associated Bacteria Toward a Core Stress Microbiome. mSystems 3: 17.

- Zhu L, Xu J, Dou P, Dou D, Huang L (2021) The rhizosphere soil factors on the quality of wild-cultivated herb and its origin traceability as well as distinguishing from garden-cultivated herb: Mountainous forest cultivated ginseng for example. Indust Crops Prod 172: 114078.

- Kang JP, Huo Y, Yang DU, Yang DC (2021) Influence of the plant growth promoting Rhizobium panacihumi on aluminum resistance in Panax ginseng. J Ginseng Res 45: 442-449.

- Duan Y, Wang C, Li L, Han R, Shen X, et al. (2024) Effect of Compound Fertilizer on Foxtail Millet Productivity and Soil Environment. Plants 13: 3167.

- He C, Wang R, Ding W, Li Y (2022) Effects of cultivation soils and ages on microbiome in the rhizosphere soil of Panax ginseng. Appl Soil Ecol 174: 104397.

- Shi Z, Yang M, Li K, Yang L, Yang L (2024) Influence of cultivation duration on microbial taxa aggregation in Panax ginseng soils across ecological niches. Front Microbiol 14: 1284191.

- Shingo M, Haruno D, Junko K (2022) Changes over the Years in Soil Chemical Properties Associated with the Cultivation of Ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer) on Andosol Soil. Agriculture 12: 1223.

- Fang X, Wang H, Zhao L, Wang M, Sun M (2022) Diversity and structure of the rhizosphere microbial communities of wild and cultivated ginseng. BMC microbiology 22: 2.

- Tong AZ, Liu W, Liu Q, Xia GQ, Zhu JY (2021) Diversity and composition of the Panax ginseng rhizosphere microbiome in various cultivation modesand ages. BMC microbiology 21: 18.

- Gao YG, Zang P, Zhao Y, He ZM (2022) China Ginseng. Beijing, China.

- Xu Z, Chen Y, Sui J, Wang Y, Zhang Q, et al. (2025) Effects of rhizosphere soil microecology on the content of ginsenosides in Panax ginseng. Rhizosphere 34: 101065.

- Chang SC, Jackson ML (1957) Fractionation of Soil Phosphorus. Soil Sci 84: 133-144.

- Olsen SR (1954) Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate. US Department of Agriculture, USA.

- Gusakov AV, Kondratyeva EG, Sinitsyn AP (2011) Comparison of two methods for assaying reducing sugars in the determination of carbohydrase activities. Int J Anal Chem 2011: 283658.

- Chow PS, Landhäusser SM (2004) A method for routine measurements of total sugar and starch content in woody plant tissues. Tree Physiol 24: 1129-1136.

- Bao SD (2000) Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis, Beijing, China.

- Lu RK (2000) Analytic Method of Soil Agricultural Chemistry. Beijing, China.

- Song YN, Hong HG, Son JS, Kwon YO, Lee HH, et al. (2019) Investigation of Ginsenosides and Antioxidant Activities in the Roots, Leaves, and Stems of Hydroponic-Cultured Ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer). Prev Nutr Food Sci 24: 283-292.

- Liu C, Xia R, Tang M, Chen X, Zhong B, et al. (2022) Improved ginseng production under continuous cropping through soil health reinforcement and rhizosphere microbial manipulation with biochar: a field study of Panax ginseng from Northeast China. Hortic Res 9: 108.

- Eo J, Park KC (2019) Effect of vermicompost application on root growth and ginsenoside content of Panax ginseng. J Environ Manage 234: 458-463.

- Ramabulana T, Mavunda RD, Steenkamp PA, Piater LA, Dubery IA, et al. (2015) Secondary metabolite perturbations in Phaseolus vulgaris leaves due to gamma radiation. Plant Physiol Biochem 97: 287-295.

- Piasecka A, Sawikowska A, Kuczynska A, Ogrodowicz P, Mikolajczak K, et al. (2017) Drought-related secondary metabolites of barley (Hordeum vulgare) leaves and their metabolomic quantitative trait loci. Plant J 89: 898-913.

- DesRochers N, Walsh JP, Renaud JB, Seifert KA, Yeung KK, et al. (2020) Metabolomic Profiling of Fungal Pathogens Responsible for Root Rot in American Ginseng. Metabolites 10: 35.

- Chen F, Huang Y, Cao Z, Li Y, Liu D, et al. (2022) New insights into the molecular mechanism of low-temperature stratification on dormancy release and germination of Saposhnikovia divaricata Braz J Bot 45: 1183-1198.

- Gao Y, Giese M, Brueck H, Yang H, Li Z (2013) The relation of biomass production with leaf traits varied under different land-use and precipitation conditions in an Inner Mongolia steppe. Ecol Res 28: 1029-1043.

- Su Y, Jiao M, Guan H, Zhao Y, Deji C, et al. (2023) Comparative transcriptome analysis of Saposhnikovia divaricata to reveal drought and rehydration adaption strategies. Mol Biol Rep 50: 3493-3502.

- Zhou H, Shi H, Yang Y, Feng X, Chen X, et al. (2024) Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J Genet Genomics 51: 16-34.

- Shuaib M, Azam N, Bahadur S, Romman M, Yu Q, et al, (2021) Variation and succession of microbial communities under the conditions of persistent heavy metal and their survival mechanism. Microb Pathog 150: 104713.

- Xie Y, Bu H, Feng Q, Wassie M, Amee M, et al, (2021) Identification of Cd-resistant microorganisms from heavy metal-contaminated soil and its potential in promoting the growth and Cd accumulation of bermudagrass. Environ Res 200: 111730.

- Ma LJ, Ma N, Wang BY, Yang K, et al, (2021) Ginsenoside distribution in different architectural components of Panax notoginseng inflorescence and infructescence. J Pharm Biomed Anal 203: 114221.

- Chen G, Xue Y, Yu X, Li C, Hou Y, et al. (2022) The Structure and Function of Microbial Community in Rhizospheric Soil of American Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) Changed with Planting Years. Curr Microbiol 79: 281.

- Jia Y, Sun Y, Zhang T, Shi Z, Maimaitiaili B, et al. (2020) Elevated precipitation alters the community structure of spring ephemerals by changing dominant species density in Central Asia. Ecol Evol 10: 2196-2212.

- Felsmann K, Baudis M, Kayler ZE, Puhlmann H, Ulrich A, et al. (2017) Responses of the structure and function of the understory plant communities to precipitation reduction across forest ecosystems in Germany. Ann For Sci 75: 681-687.

- Hei J, Li Y, Wang Q, Wang S, He X (2024) Effects of Exogenous Organic Acids on the Soil Metabolites and Microbial Communities of Panax notoginseng from the Forest Understory. Agronomy 14: 601.

- Lee J, Mudge KW (2013) Gypsum effects on plant growth, nutrients, ginsenosides, and their relationship in American ginseng. Hortic Environ Biotechnol 54: 228-235.

- Rahimi S, Kim YJ, Yang DC (2015) Production of ginseng saponins: elicitation strategy and signal transductions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99: 6987-6996.

- You J, Liu X, Zhang B, Xie Z, Hou Z, et al. (2015) Seasonal changes in soil acidity and related properties in ginseng artiffcial bed soils under a plastic shade. J Ginseng Res 39: 81-88.

- Zhou L, Yue Q, Zhao L, Cui R, Liu X (2018) Effect of Nitrogen Level on Growth and Metabolism of Allium fistulosum Atlantis Press, Netherland.

- Sun JB, Gao YG, Zang P, Yang H, Zhang LX (2013) Mineral elements in root of wild Saposhnikovia divaricata and its rhizosphere soil. Biol Trace Elem Res 153: 363-370.

- Tsujii Y, Onoda Y, Kitayama K (2017) Phosphorus and nitrogen resorption from different chemical fractions in senescing leaves of tropical tree species on Mount Kinabalu, Borneo. Oecologia 185: 171-180.

- Pang J, Ryan MH, Lambers H, Siddique KH (2018) Phosphorus acquisition and utilisation in crop legumes under global change. Curr Opin Plant Biol 45: 248-254.

- VÁGÓ I, TOLNER L, LOCH J (2009) Effect of chloride anionic stress on the yield amount and some quality parameters of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa). Cereal Res Commun 37: 81-84.

- Val-Torregrosa B, Bundo´ M, Segundo BS (2021) Crosstalk between nutrient signalling pathways and immune responses in rice. Agriculture 11: 747-767.

- Wu D, Xiong F, Wang H, Liu S, Zhu J, et al. (2024) Temperature seasonality and soil phosphorus availability shape ginseng quality via regulating ginsenoside contents. BMC Plant Biol 24: 824.

- Ou X, Cui X, Zhu D, Guo L, Liu D, et al. (2020) Lowering Nitrogen and Increasing Potassium Application Level Can Improve the Yield and Quality of Panax notoginseng. Front Plant Sci 11: 595095.

- Zhao F, Zhang Y, Li Z, Shi J, Zhang G, et al. (2020) Vermicompost improves microbial functions of soil with continuous tomato cropping in a greenhouse. J Soils Sediments 20: 380-391.

- Meng X, Li Y, Yao H, Wang J, Dai F, Wu Y, et al. (2020) Nitrification and urease inhibitors improve rice nitrogen uptake and prevent denitrification in alkaline paddy soil. Appl Soil Ecol 154: 103665.

- Schimel J, Becerra CA, Blankinship J (2017) Estimating decay dynamics for enzyme activities in soils from different ecosystems. Soil Biol Biochem 114: 5-11.

- Xiu Y, Li X, Sun X, Xiao D, Miao R, et al. (2019) Simultaneous determination and difference evaluation of 14 ginsenosides in Panax ginseng roots cultivated in different areas and ages by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in the multiple reaction-monitoring mode combined with multivariate statistical analysis. J Ginseng Res 43: 508-516.

- Yu L, Chen Y, Shi J, Wang R, Yang Y, et al, (2019) Biosynthesis of rare 20(R)-protopanaxadiol/protopanaxatriol type ginsenosides through Escherichia coli engineered with uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferase genes. J Ginseng Res 43: 116-124.

- Spear GT, French AL, Gilbert D, Zariffard MR, Mirmonsef P, et al. (2014) Human α-amylase present in lower-genital-tract mucosal fluid processes glycogen to support vaginal colonization by Lactobacillus. J Infect Dis 210: 1019-1028.

- Nasioudis D, Beghini J, Bongiovanni AM, Giraldo PC, Linhares IM, et al. (2015) α-Amylase in Vaginal Fluid: Association With Conditions Favorable to Dominance of Lactobacillus. Reprod Sci 22: 1393-1398.

- Nunn KL, Clair GC, Adkins JN, Engbrecht K, Fillmore T, et al. (2020) Amylases in the Human Vagina. mSphere 5: 943-920.

- Palaniyandi SA, Suh JW, Yang SH (2017) Preparation of Ginseng Extract with Enhanced Levels of Ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 Using High Hydrostatic Pressure and Polysaccharide Hydrolases. Pharmacogn Mag 13: 142-147.

- Dinesh R, Anandaraj M, Kumar A, Bini YK, Subila KP, et al. (2015) Isolation, characterization, and evaluation of multi-trait plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for their growth promoting and disease suppressing effects on ginger. Microb Res 173: 34-43.

- Ali S, Hameed S, Shahid M, Iqbal M, Lazarovits G, et al. (2020) Functional characterization of potential PGPR exhibiting broad-spectrum antifungal activity. Microbiol Res 232: 26389.

Citation: Xu Z, Chen Y, Wang Y, Sui J, Xue Y, et al. (2025) Potential Role of soil Parameters in Quality Formation of 1-Year-Old Ginseng Based on Correlation Analysis. HSOA J Altern Complement Integr Med 11: 666.

Copyright: © 2025 Zhefeng Xu, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.