Psoriasis Impact Question (PIQ): A Clinical Tool to Assess Specifically the Impact of Psoriasis on Quality of Life

*Corresponding Author(s):

Marc BourcierFaculty Of Medicine, Université De Sherbrooke, Moncton, NB, Canada

Email:mbourcier@rogers.com

Abstract

Background: One of the most important aspects of psoriasis is its potential for a profound impact on the quality of life (QoL) of patients. The knowledge of its impact is crucial for the physician to adequately manage the disease. Several patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to assess the impact of skin conditions on QoL have been developed, but there is a lack of a practical and specific PROM to assess psoriasis on QoL.

Objectives: This study aims to provide physicians with a simple tool for assessing QoL in patients with psoriasis.

Methods: Comparison between the Psoriasis Impact Question (PIQ) and the validated Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) involved 81 patients with psoriasis across Canada.

Results: Results indicated higher PIQ scores than DLQI, with a correlation coefficient of 0,71 linking the 2 questionnaires.

Conclusion: PIQ score interpretation may be similar to that of DLQI, reflecting psoriasis effects on QoL. Easily integrated into clinical settings within seconds, it has the potential to be used for regulatory purposes and drug approval.

Keywords

Psoriasis; Patient-reported outcome measure (PROM); Single-item questionnaire; Quality of life (QoL)

Introduction

A revolution in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis occurred upon the discovery that the immune system plays a major role in its pathophysiology. New promising therapeutic targets are still emerging. There are well-defined assessment tools to measure the objective signs and symptoms of psoriasis, including PASI, SPASI, SaPASI, NAPSI, PSI, BSA, and PGA, routinely used in clinical trials [1-4]. The other equally important issue is to evaluate changes in the Quality of Life (QoL). Several Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) have been developed to address this issue. Psoriasis and its comorbidities have an association with psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety [5]. Its impact on self-confidence, on coping mechanisms, and the impact of symptoms and burden of treatment, all need to be considered while treating patients with psoriasis [6].

Questionnaires to measure the impact of a disease on patients' QoL are important PROMs. Given the great impairment of QoL caused by psoriasis, there is a lack of a practical and simple assessment specific to this condition. There are several PROMs specific to psoriasis; Kitchen et al. identified a total of 16. Of them, nine assessed the impacts of psoriasis on QoL among other things; CALIPSO, IPSO, PSORIQoL, PDI, PRISM, PQLQ, KMPI, PLSI, and NPQ10 [7-16]. Most of these PROMs are unsuitable because of the number of items, time for completion, complexity, and lack of applicability [7].

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is the most frequently used PROM to evaluate the impact of psoriasis on QoL [17]. Published in 1994 by Dr. Andrew Finlay, the DLQI questionnaire evaluates the impact of skin diseases on QoL. It is not specific to psoriasis and may also underscore the real impact of psoriasis on QoL. Despite this, it has been used to evaluate the impact of treatment on QoL in most therapeutic trials of psoriasis. What is needed in a busy clinic is a simple and standard tool to assess QoL. The Psoriasis Impact Question (PIQ) was developed for such a setting. This single-item questionnaire was designed to provide a quick overview of the impact of psoriasis on a patient's QoL.

This study aims to provide physicians with a simple tool for assessing QoL in patients with psoriasis. Its objective is to provide clinicians with prompt information, facilitating more suitable treatments for their patients.

Methods

- Data source

Approval from the ethical committee for this project was not required as it was using existing data or records with no identifiable data.

An invitation letter was sent to eight dermatologists with a special interest in psoriasis across Canada. Data was collected from January to December 2018. The physicians were asked to record data on the next ten new patients consulting for psoriasis with a Body Surface Area (BSA) of ≥ 5%. After obtaining consent, the physicians recorded the patient’s age, gender, duration of psoriasis, BSA, and Physician Global Assessment (PGA). It was also recorded whether or not the face, genitals, and hands were affected. Patients were instructed to respond to the PIQ question using whole metric numbers and to complete the original DLQI questionnaire.

- Development of PIQ

PIQ was developed to fill the need for a simple and specific PROM assessing the impact of psoriasis on the overall patient’s QoL. It has been observed that DLQI scores did not always reflect the true impact of psoriasis on QoL. An example of this is an experience with a patient affected by severe psoriasis who had a DLQI score of 9. He was asked the PIQ and scored 27. This seemed to be more reflective of the profound impact on his QoL, considering that the severity of the disease had led him to contemplate suicide. PIQ was subsequently incorporated into a clinical setting, and carried out for research purposes as it seemed easily comprehensible to patients, had minimal administrative burden and demonstrated correlation with validated questionnaires.

- Assessment of PIQ

Dermatologists assessed the impact of psoriasis on QoL by prompting patients to complete the PIQ. The PIQ is as follows:

How is psoriasis affecting you (as a whole) on a scale of 0 to 10, taking into consideration treatment burden, control of the disease, effect on your daily or family activities, or anything that bothers you with this condition?

The scoring of PIQ is in whole metric numbers, ranging from 0 to 10, “0” being no impact on QoL and 10 being the highest possible impairment of QoL. The score is then multiplied by 3 to give a final score ranging from 0 to 30.

- Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel software. Associations between demographics, clinical characteristics, and both PIQ and DLQI scores were explored with Pearson correlation coefficients. Statistical significance was calculated with the student’s T-test.

Results

Population

Sociodemographic data are shown in Table 1. Out of 83 patients, 2 did not complete the DLQI and were excluded from our analysis. 81 patients were included in the study, of whom 43 were women and 38 were men. Patients were aged from 20 to 74 years with a mean age of 46,9 (SD=13,1 years).

|

|

N (%) |

|

Age (years) 20-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 |

17 (20,9) 18 (22,2) 19 (23,5) 19 (23,5) 8 (9,9) |

|

Duration of psoriasis (years) 0-4 5-14 15-24 25-34 35-44 45-60 |

13 (16,4) 20 (25,3) 20 (25,3) 14 (17,7) 9 (11,4) 3 (3,8) |

|

BSA (%) 0-4 5-9 ≥10 |

4 (4,9) 30 (37) 47 (58) |

Table 1: Sociodemographic data.

Duration of psoriasis ranged from less than a year to 60 years with a mean of 18,9 (SD=13,5 years). The mean BSA was 12,6% (SD= 8,3) ranging from 2 to 42%. PGA had a mean of 3,1 (SD= 0,6) and a median of 3.

Data analysis

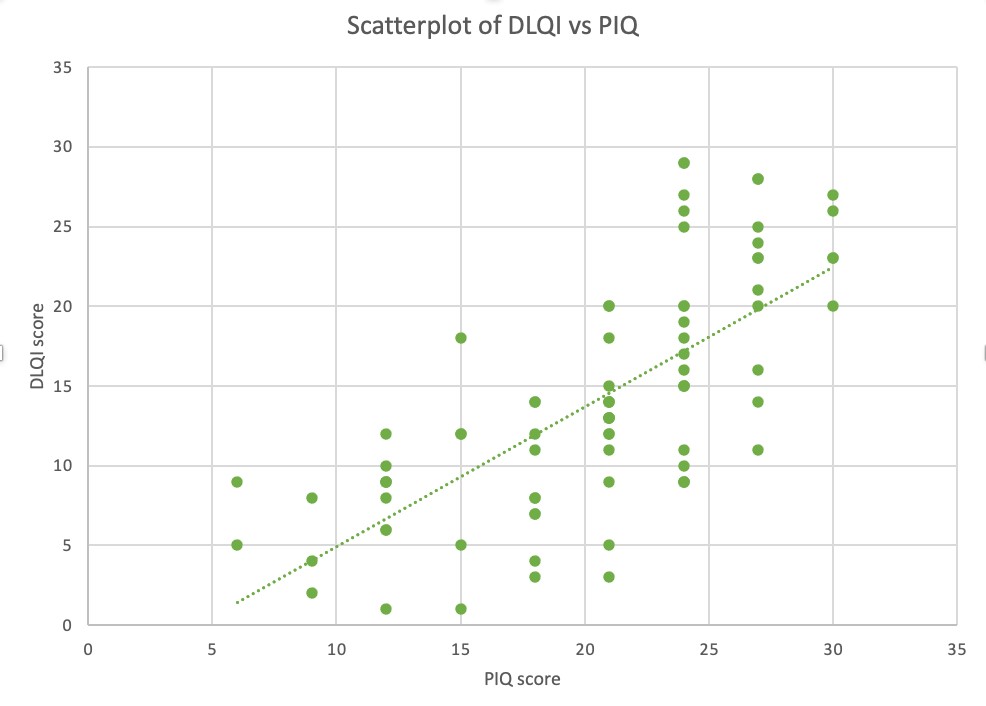

PIQ and DLQI scores are shown in Table 2. The PIQ had a mean of 21 (SD=5,9) and a median of 21. The DLQI had a mean of 14,1 (SD=7,4) and a median of 13. PIQ scores and mean were both higher than the DLQI (p<0,001). The correlation linking DLQI and PIQ demonstrated a strong association (R=0,71). The relationship between DLQI and PIQ is shown in Figure 1.

|

|

N (%) |

|

PIQ score 0-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-30 |

0 5 (6,2) 9 (11.1) 15 (18,5) 36 (44.4) 16 (19,8) |

|

DLQI score 0-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-30 |

7 (8,6) 19 (23,5) 22 (27,1) 11 (13,1) 12 (14,8) 10 (12,3) |

Table 2: Score distribution of QoL assessment tools of patients with psoriasis.

Figure 1: Scatterplot of DLQI vs PIQ scores.

Figure 1: Scatterplot of DLQI vs PIQ scores.

This scatterplot shows a moderate to strong positive linear association between DLQI and PIQ scores. Each point represents a patient and indicates the value of their DLQI and PIQ scores. Some points represent more than one patient, some of them having identical scores.

PIQ scores were higher in women (mean= 21,7, SD= 5,1) than in men (19,2, SD= 6,6, p < 0,001). DLQI scores were also higher in women (15, SD= 7,3) than in men (13,1, SD= 7,5, p < 0,001). The correlation coefficient linking DLQI and PIQ correlated more strongly with men (R=0,78) than with women (R=0,62). PIQ scores correlated with BSA (R=0,39), and the DLQI correlated with BSA (R=0,42). Age had a weak impact on the scores of both DLQI and PIQ, as the coefficients –0,01 (age/DLQI) and -0,06 (age/PIQ) were both low.

Out of 81 patients, 28 (33,7%) had genital involvement. PIQ score was higher in patients with genital involvement (mean=23,4, SD=4,9) than with no genital involvement (19,0, SD= 5,9). DLQI scoring was also higher with genital involvement (mean =17,9, SD= 7,7) than without genital involvement (12,1, SD=6,4, p < 0.01).

Discussion

To be useful in a clinical setting, PROMs must be quick to complete, require no supervision, have easily understandable scores, and provide helpful information to the clinician [18]. The PIQ fulfils these criteria and could improve treatment decisions.

Several PROMs have been used in studies, but most of them are not useful in clinical practice. Questionnaires to assess QoL such as Short form-36 (SF-36) are described but are not specific to skin diseases [19], and are then less useful to dermatologists. Skindex is specific to dermatology but is lengthy even though there are revised versions with fewer items [20,21]. The most widely used PROM to assess dermatological conditions is the DLQI. For psoriasis specifically, not one of the 16 PROMs identified by Kitchen et al. demonstrated validity, reliability, sensitivity to changes, and specificity to psoriasis [7]. No single-item questionnaire assessing the impact on QoL from psoriasis is found in the literature.

Results analysis shows the value of PIQ. The PIQ absolute mean score was higher than the DLQI. Both of them correlate by a coefficient of 0,71, a moderate to strong positive relationship. A perfect correlation would suggest that PIQ is on par with DLQI, potentially making the use of PIQ redundant, given the presence of an existing validated PROM for the same matter. PIQ scores trend higher, which could indicate a more accurate reflection of the specific impact of psoriasis on quality of life. On the other hand, it also tells us that the DLQI is a good questionnaire of skin diseases on patients' QoL.

The DLQI covers six domains: symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, school and work, personal relationships, and treatment [17]. These are represented by ten distinct questions. Our approach indirectly includes those headings without favouring any particular one. We aim for the patient to answer the PIQ based on what holds the most significance for their QoL. The PIQ score, specific to psoriasis, can efficiently assess the global impact of psoriasis on QoL. On the other hand, a score derived from a single-item questionnaire could lead to inconsistencies in its interpretation. A single-item measure may not capture the full complexity of the disease, but it is believed that the general question in the PIQ allows patients to express the impact of psoriasis on QoL, regardless of their subtype or severity. In fact, numerous publications have shown that the impact on QoL, as assessed by DLQI, often correlates poorly with PASI scores [22,23].

There is no validated descriptor for the interpretation of PIQ’s score. The range of the PIQ score is 0 to 30, the same as the DLQI. This scoring structure was chosen to facilitate the interpretation of the PIQ, as dermatologists are already familiar with the DLQI score ranging from 0 to 30. The validated band descriptors for the DLQI interpretation were described in 2005 [17]. The use of DLQI’s band descriptors for the interpretation of PIQ scores was not studied, making validation an area of potential interest.

While many PROMs specify a recall period, the PIQ omits this to overcome any potential daily or weekly mood and activity variation. We believe that the impact of QoL should be assessed without a timeframe, eliminating the need for patients to concentrate on a specific period. However, the lack of a timeframe may overlook subtle changes over time.

QoL cannot be described by a number because of its subjectivity. Despite this fact, we need tools to address this aspect of psoriasis as it might be the most relevant to patients. The number obtained by PIQ will assist dermatologists and healthcare professionals in quantifying the extent of the impact of psoriasis on their patients’ QoL.

The cost associated with systemic treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis is substantial. Patients are required to fulfill certain criteria, one of them assessing the impact on their QoL. It is believed that the DLQI might underestimate the real effect of psoriasis on their quality of life, as DLQI scores tend to be lower. The PIQ may offer a solution to this limitation, but there is currently no evidence of the latter.

The formulation of the PtGA-NRS [24], a validated PROM, is similar to that of the PIQ in that both assess patient-reported outcomes using a single, straightforward question. The key difference is that the former evaluates the severity of psoriasis, while the latter evaluates its impact on QoL. The simplicity of this global question makes it easily comprehensible for physicians, and we assume that patients from diverse backgrounds could grasp PIQ, although we did not obtain patients' perspectives. Although the validated PtGA-NRS shares similarities with the PIQ, it would be important to include patient feedback to assess their comprehension of the PIQ in the future. Despite its simplicity, the PIQ likely offers an authentic evaluation of how psoriasis affects our patients' lives.

Subgroup analyses could not be conducted given the relatively small number of patients in this study. However, applying the PIQ to a larger cohort would facilitate further evaluation, including validation in specific populations such as patients with genital involvement. This would also allow for meaningful subgroup analyses, particularly in areas where existing tools like the DLQI have limitations, such as scalp, genital and palmoplantar psoriasis. As PIQ was administered once, test reliability and its response to treatment were not recorded. The goal of the study was to include patients with psoriasis with a BSA >5%, but four of our participants had BSA under 5%. Responsiveness was not evaluated in this study, and the application of standard methods to validate a PROM would be necessary in future studies for the formal validation of the PIQ.

Conclusion

Significant progress has been made in psoriasis research. Numerous safe and effective treatments are now available, with more to come to enhance psoriasis management. For dermatologists to choose an appropriate agent, understanding the impact of the disease on their patients is crucial. While many PROMs exist, none are ideal due to factors like length, complexity or applicability. PIQ is reflective of the patient’s subjective experience, is quick to complete, and is easy to understand. Although a single-item instrument may not fully capture the complexity or individual nuances of psoriasis, it nonetheless offers a specific and practical tool that is easily implementable in any clinical setting. The PiQ correlates with the DLQI, enabling similar interpretation, and may prove particularly valuable in subgroups where the DLQI falls short. The PIQ is a promising step toward more accessible and targeted assessment of QoL in psoriasis care.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Andrew Finlay (Cardiff University School of Medicine) for his helpful suggestions.

Data Availability

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest about this initiative.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References

- Louden BA, Pearce DJ, Lang W, Feldman SR (2004) A Simplified Psoriasis Area Severity Index (SPASI) for rating psoriasis severity in clinic patients. Dermatol Online J 10: 7.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Reboussin DM, Rapp SR, Exum ML, et al. (1996) The self-administered psoriasis area and severity index is valid and reliable. J Invest Dermatol 106: 183-186.

- Rich P, Scher RK (2003) Nail psoriasis severity index: a useful tool for evaluation of nail psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 49: 206-212.

- Martin ML, McCarrier KP, Chiou CF, Gordon K, Kimball AB, et al. (2013) Early development and qualitative evidence of content validity for the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory (PSI), a patient-reported outcome measure of psoriasis symptom severity. J Dermatolog 24: 255-260.

- Khawaja AR, Bokhari SM, Tariq R, Atif S, Muhammad H, et al. (2015). Disease Severity, Quality of Life, and Psychiatric Morbidity in Patients With Psoriasis With Reference to Sociodemographic, Lifestyle, and Clinical Variables: A Prospective, Cross-Sectional Study From Lahore, Pakistan. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 17: 10.

- García-Sánchez L, Montiel-Jarquín ÁJ, Vázquez-Cruz E, May-Salazar A, Gutiérrez-Gabriel I, et al. (2017) Calidad de vida en el paciente con psoriasis [Quality of life in patients with psoriasis]. Gac Med Mex 153: 185-189.

- Kitchen H, Cordingley L, Young H, Griffiths C, Bundy C (2015) Patient-reported outcome measures in psoriasis: the good, the bad and the missing! Br J Dermatol 172: 1210-1221.

- Sampogna F, Styles I, Tabolli S, Abeni D (2011) Measuring quality of life in psoriasis: the CALIPSO questionnaire. Eur J Dermatol 21: 67-78.

- McKenna KE, Stern RS (1997) The impact of psoriasis on the quality of life of patients from the 16-center PUVA follow-up cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol 36: 388-394.

- McKenna SP, Cook SA, Whalley D, Doward LC, Richards HL, et al. (2003) Development of the PSORI-QoL, a psoriasis-specific measure of quality of life designed for use in clinical practice and trials. Br J Dermatol 149: 323-331.

- Finlay AY, Kelly SE (1987) Psoriasis-an index of disability. Clin Exp Dermalogy 12: 8-11.

- Mühleisen B, Buchi S, Schmidhauser S, Jenewein J, French LE, et al. (2009) Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure (PRISM): a novel visual instrument to measure quality of life in dermatological inpatients. Arch Dermatol 145: 774-780.

- Inanir I, Aydemir O, Gunduz K, Danaci AE, Türel A, et al. (2006) Developing a quality of life instrument in patients with psoriasis: the Psoriasis Quality of Life Questionnaire (PQLQ). Int J Dermatol 45: 234-238.

- Feldman SR, Koo JY, Menter A, Bagel J (2005) Decision points for the initiation of systemic treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 53: 101-107.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK (1995) The Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory: a preliminary index of psoriasis-related stress. Acta Derm Venereol 75: 240-243.

- Ortonne JP, Baran R, Corvest M, Schmit C, Voisard JJ, et al. (2010) Development and validation of nail psoriasis quality of life scale (NPQ10). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venreol 24: 22-27.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK (1994) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 19: 210-216.

- Finlay AY (2015) Patient-reported outcome measures in psoriasis: assessing the assessments. Br J Dermatol 172: 1178-1179.

- Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JEJr (1988) The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 26: 724-735.

- Chren MM (2012) The Skindex instruments to measure the effects of skin disease on quality of life. Dermatol Clin 30: 231-236.

- Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY (2005) Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol 125: 659-664.

- Yang J, Hu K, Li X, Hu J, Tan M, et al. (2023) Psoriatic Foot Involvement is the Most Significant Contributor to the Inconsistency Between PASI and DLQI: A Retrospective Study from China. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology 16: 443-451.

- Maul JT, Maul LV, Didaskalu JA, Valenzuela F, Romit R et al. (2024) Correlation between Dermatology Life Quality Index and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index in Patients with Psoriasis: A cross-sectional global healthcare study on psoriasis. Acta DV 104: 20329.

- Yu N, Peng C, Zhou J, Gu J, Xu J, et al. (2023) Measurement properties of the patient global assessment numerical rating scale in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 189: 437-444.

Citation: Bourcier M, Breau M (2025) Psoriasis Impact Question (PIQ): A Clinical Tool to Assess Specifically the Impact of Psoriasis on Quality of Life. J Clin Dermatol Ther 10: 0152.

Copyright: © 2025 Marc Bourcier, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.