Pulmonary Amyloidosis Presenting as Recurrent Pleural Effusion and Hemoptysis Leading to Pulmonary Infarction and Fatal Cardiopulmonary Arrest: A Case Report

*Corresponding Author(s):

Rajeev DhuparDepartments Of Cardiothoracic Surgery And Critical Care Medicine, University Of Pittsburgh School Of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Tel:412-623-2025,

Email:dhuparr2@upmc.edu

#Equal contribution

Abstract

Background: Amyloidosis is a disease caused by deposition of protein fibrils throughout the body leading to a wide range of clinical presentations. Pulmonary amyloidosis is a rare disorder that has many manifestations, making prompt diagnosis and treatment difficult. Pulmonary involvement is typically divided into three subtypes including tracheobronchial, nodular pulmonary, and diffuse alveolar-septal amyloidosis. Pulmonary amyloidosis can often be mistaken for pneumonia or malignancy with symptoms ranging from recurrent pleural effusions to fatal pulmonary hemorrhage.

Case Presentation: In this case report, we describe a 63year-old male who initially presented with dyspnea, recurrent pleural effusions, bilateral consolidations, and small volume hemoptysis. Ultimately, this culminated in massive hemoptysis and cardiopulmonary failure. Autopsy demonstrated diffuse alveolar amyloidosis with large pulmonary infarcts from deposition of amyloid in blood vessel walls.

Conclusion: Pulmonary amyloidosis is a challenging diagnosis that can have fatal consequences, but early suspicion may allow for early diagnostic procedures, change in management, and improved outcomes.

Keywords

Case report; Hemoptysis; Pleural effusion; Pulmonary amyloidosis

Abbreviations

AL - Amyloid Light Chain

ANA - Antinuclear Antibody

ANCA - Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody

CT - Computed Tomography

PEA - Pulseless-Electrical Activity

Background

Amyloidosis is a group of disorders caused by the build-up and deposition of protein fibrils in tissues and organs. Amyloid fibrils form β-pleated sheets that have a unique staining property under polarized light. These fibrils can accumulate anywhere in the body from the heart to the kidneys leading to restrictive cardiomyopathy and nephropathy respectively. Amyloidosis is biochemically classified based on the type of abnormal protein in the fibril deposits and whether they are systemic or localized. Amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis occurs as a result of overabundance of immunoglobulin light chain and arises from clonal B cells. It is often associated with myeloma. Amyloid A refers to accumulation of normal acute phase reactants due to chronic systemic inflammatory conditions [1]. This case report describes a rare case of pulmonary amyloidosis that initially presented as recurrent pleural effusions and lung consolidations, but ultimately led to massive hemoptysis and cardiopulmonary failure.

Case Presentation

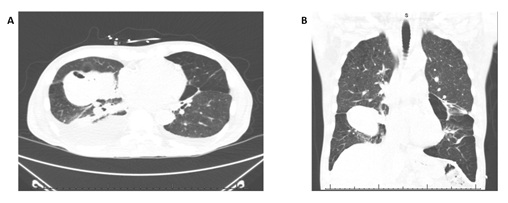

A 63year-old male with a history of 40 pack-year smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (FEV1 40% and DLCO 49%) presented with progressive dyspnea, small volume hemoptysis, and bilateral lower extremity swelling. He was found to have a right pleural effusion attributed to newly diagnosed diastolic heart failure. Thoracentesis was performed draining 1.3 L of transudative fluid. He was started on furosemide and discharged after improvement of his symptoms. The patient returned several weeks later with recurrent shortness of breath and hemoptysis. A non-contrast Computed Tomography (CT) scan revealed bilateral consolidations, cavitary lesions in the right middle/lower lobes, and a recurrent right pleural effusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Non contrast computed tomography scan demonstrating right lower lobe cavitary lesion, (A) axial view and (B) coronal view.

Figure 1: Non contrast computed tomography scan demonstrating right lower lobe cavitary lesion, (A) axial view and (B) coronal view.

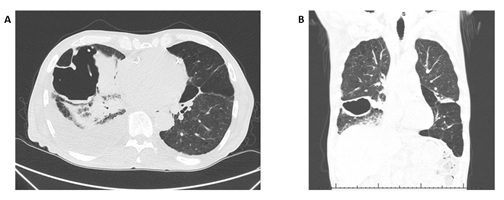

A repeat thoracentesis yielded 1L of blood-tinged exudative fluid. The patient was started on IV antibiotics due to suspicion for pneumonia and parapneumonic effusion. The pleural fluid cultures and cytology were negative. The patient was discharged on oral antibiotics but returned several days later with similar symptoms. This time the contrast chest CT demonstrated persistent cavitary lesion concerning for evolving abscess (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Evolution of right lower lobe cavitary lesion later confirmed as a pulmonary infarct, (A) axial view and (B) coronal view.

Figure 2: Evolution of right lower lobe cavitary lesion later confirmed as a pulmonary infarct, (A) axial view and (B) coronal view.

He was started on ampicillin-sulbactam and a pigtail catheter was placed in the effusion, draining 3L of exudative pleural fluid. Pleural fluid studies were sent for tuberculosis, cryptococcus, aspergillus and histoplasma all of which were negative. He was initiated on voriconazole due to rare fungal spores and pseudohyphal forms on sputum cytology. Bedside chemical pleurodesis with doxycycline was performed due to recurrent pleural effusions and the pigtail was removed the following day. The patient was discharged after several days of stable chest radiographs. He was re-admitted a week later with a repeat non-contrast CT scan showing a loculated pleural effusion. He was taken to the OR for drainage and decortication for suspected empyema, however he arrested after induction of anesthesia. Bronchoscopy revealed blood in the proximal airways but none in the oropharynx. Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved, and he was transferred to the intensive care unit. Over the following days the patient remained critically unstable with high oxygen requirements and norepinephrine to maintain adequate blood pressure. He had two Pulseless-Electrical Activity (PEA) arrests over the ensuing days. During both arrests, a large amount of bright red blood was noted in the endotracheal tube prompting bronchoscopy with no clear bleeding source. Notably, during this admission, the patient had a positive Antinuclear Antibody(ANA) (ANA, 1:160 speckled pattern), elevated proteinase-3 autoantibodies, elevated myeloperoxidase autoantibodies, and low C3, C4 complement levels. Further work-up with serum protein electrophoresis and light chain levels revealed hypogammaglobinemia and an elevation of serum free kappa light chain with abnormal kappa/lambda ratio. The patient’s vasopressor requirements continued to escalate and clinical status declined despite maximum medical care. The family elected to follow comfort care in accordance with his wishes and the patient died shortly after. On autopsy, the patient was found to have systemic arterial amyloidosis involving the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, and pancreas with periarterial amyloid deposits in nearly every major organ system. The right lower lobe cavitary lesions were found to be pulmonary infarcts from severe arterial amyloidosis with bilateral hemorrhagic consolidations. The heart demonstrated significant amyloid deposition in the coronary arteries and the myocardium. The cause of death was attributed to cardiopulmonary arrest from systemic arterial amyloidosis.

Discussion

Pulmonary amyloidosis has three primary presentations consisting of tracheobronchial amyloidosis, nodular pulmonary amyloidosis, and diffuse alveolar-septal amyloidosis. While diffuse alveolar-septal amyloidosis is normally related to the systemic AL form, tracheobronchial and nodular pulmonary involvement are generally due to localized production of AL light chains. Diffuse-alveolar septal involvement results in deposition of amyloid in the distal airways, alveoli, septal walls, and blood vessels which may lead to restrictive lung function and pulmonary hemorrhage. Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis occurs in the setting of bilateral nodules or cystic masses consisting of immunoglobulin light chains produced by a localized process. These bilateral masses are often mistaken for a multifocal pneumonia or malignancy. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis similarly results from localized production of AL light chains that are deposited in the proximal airways. This form may manifest as dyspnea, cough, or hemoptysis related to airway damage or obstruction [2]. Few cases have been reported on pulmonary amyloidosis and its various manifestations. Invariably, these cases have led to massive pulmonary hemorrhage and death before the diagnosis was discovered. One of the earliest cases reported by [3] in 1983 described a patient with intermittent hemoptysis who later died of massive pulmonary hemorrhage [3]. This patient was found to have amyloid extending into alveolar septa and blood vessel walls, similar to subsequent reported cases. Another case report by [4] detailed a patient presenting with dyspnea, recurrent pleural effusions, and hemoptysis who was found to have systemic amyloidosis and diffuse alveolar septal amyloidosis. In a similar fashion, this patient succumbed to massive pulmonary hemorrhage before the diagnosis was confirmed. Notably, on bronchoscopy, no bleeding source was identified [4]. In a rare case describing the successful treatment of pulmonary amyloidosis, [5] reported a patient with small-volume intermittent hemoptysis and dyspnea who was treated with steroids for presumed vasculitis. Notably, this patient had positive antinuclear antibody titers and atypical Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA) along with negative myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3. Only after stabilization and wedge resection was the patient found to have severe diffuse alveolar hemorrhage from pulmonary amyloidosis [5]. Another case report by Yong et. al. described a patient who presented with recurrent exudative pleural effusions. An incidental pulmonary infarct was discovered during their work-up which was attributed to a pulmonary embolism. After wedge biopsy, the diagnosis of pulmonary amyloidosis was confirmed, and the infarct was believed to be related to amyloid deposition [6]. In two more recent cases, patients who died from massive pulmonary hemorrhage initially presented with small-volume hemoptysis and normal bronchoscopy. In both cases, patients were treated for pneumonia based on the discovery of bilateral consolidations later found to be pulmonary infarcts from vascular amyloidosis [7,8] In this report, a notable similarity to previous cases include small volume hemoptysis with no clear bleeding source on bronchoscopy. These initial minor bleeding episodes are often the herald for massive pulmonary hemorrhage and death. Nearly half of the reports also describe pulmonary infarcts, which led to the large cavitary lesion in this case. Notably, the patient also had positive myeloperoxidase, proteinase-3, and ANA, not demonstrated in previous cases. Our patient was also found to have hypogammaglobulinemia on serum protein electrophoresis and elevated serum free light chains. In nearly all cases previously described, the diagnosis of amyloidosis was only made after death. Given that the clinical signs of systemic amyloidosis are relatively nonspecific, there was no clear indication of the diagnosis, although every case was a result of AL light chain deposition. Although not confirmed on autopsy, the elevation in free light chains in this case points to systemic AL amyloidosis. This suggests that pulmonary amyloidosis may present in a more insidious manner given its predisposition for localized disease. These reports also raise the importance of recognizing patients at risk for pulmonary amyloidosis given the dismal outcomes.

Conclusion

A high degree of suspicion for pulmonary amyloidosis should be held in those patients presenting with small volume hemoptysis, normal bronchoscopy, recurrent pleural effusions, and pneumonic consolidations. Despite previous cases of pulmonary amyloidosis in the literature, this report suggests that recognition and treatment of this condition continues to be a challenge.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The requirement for consent was waived for this case report as no identifiable information was reported, the patient was deceased, and there were no family members who participated in their care.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable, patient was deceased and has no relatives who participated in their care.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Any information is available on request by email from the corresponding author (RD)

Competing Interests

None

Funding

RD was supported by funding from a Department of Veteran’s Affairs Career Development Award (CX001771-01A2)

Author’s Contribution

All authors read and approved the final manuscript and are personally accountable for their contributions to this work. BF and CI obtained, analyzed, and interpreted patient data, and drafted the work; CB and RD made substantial contributions to conception and revision.

Acknowledgement

None

References

- Wechalekar AD, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN (2016) Systemic amyloidosis. Lancet 387: 2641-2654.

- Khoor A, Colby TV (2017) Amyloidosis of the Lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med 141: 247-254.

- Lee AB, Bogaars HA, Passero MA (1983) Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis. A cause of bronchiectasis and fatal pulmonary hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med 143: 603-604.

- Sterlacci W, Veits L, Moser P, Steiner HJ, Ruscher S, et al. (2009) Idiopathic systemic amyloidosis primarily affecting the lungs with fatal pulmonary haemorrhage due to vascular involvement. Pathol Oncol Res 15: 133-136.

- Shenin M, Xiong W, Naik M, Sandorfi N (2010) Primary amyloidosis causing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. J Clin Rheumatol 16: 175-177.

- Dai Y, Liu C, Chen J, Zeng Q, Duan C (2019) Pleural amyloidosis with recurrent pleural effusion and pulmonary embolism: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 98: 14151.

- Chung JH, Sharma A, Mino-Kenudson M, Lanuti M, Shepard JA, et al. (2010) Amyloidosis presenting as pulmonary infarcts: a case report. J Thorac Imaging 25: 138-140.

- Morgenthal S, Bayer R, Schneider E, Zachäus M, Röcken C, et al. (2016) Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis with spontaneous fatal blood aspiration. Forensic Sci Int 262: 1-4.

Citation: Fisher B, Ikeji C, Brackney C, Dhupar R (2022) Pulmonary Amyloidosis Presenting as Recurrent Pleural Effusion and Hemoptysis Leading to Pulmonary Infarction and Fatal Cardiopulmonary Arrest: a case report. Archiv Surg S Educ 4: 043.

Copyright: © 2022 Bryant Fisher, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.