Quality of Life and End Stage Kidney Disease: Conceptual and Theoretical Issues

*Corresponding Author(s):

Issa Al SalmiThe Renal Medicine Department, The Royal Hospital, Oman Medical Specialty Board, Muscat, Oman

Tel:968 92709000,

Fax:968 24599966

Email:isa@ausdoctors.net

Abstract

Background

Quality of Life (QoL) and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) are multidimensional concepts. Several tools have been developed to measure these concepts. The aim of this narrative review is to gain a general understanding of QoL concepts, track its theoretical development, and identify the theoretical framework underpinning the concept.

Method

SCOPUS, Cochrane Library, Pro Quest (ASSIA) and EBSCO (CINAHL and Medline) were the main databases searched. Secondary internet resources(Science Direct and Pub Med), and non-electronically published relevant articles were also searched. English was the only language used in the search. Joined and separate keywords were used to find the published literature that discussed QoL generally across all disciplines.

Results

A total of 85 articles met the inclusion criteria: 27 empirical studies and58 discussion articles (7 HRQoL, 18 concept analyses, 21 QoL definitions and 12 papers were related to different factors of QoL and HRQoL). Four substantial determinants were identified which related to the concepts of QoL and HRQoL among ESKD patient: functional status, co-morbidities, socio-demographic factors, and spirituality. Three main approaches are being used to assess QoL and HRQoL: Generic, disease-specific and individualized measurement measures.

Conclusion

The terms QoL is used interchangeably with other relate terms such as HRQoL, health, and well-being which may cause confusion for both the researcher and the participants. Healthcare worker should utilise cross cultural knowledge and culturally sensitive skills in providing and maximising good patient care outcomes.

Keywords

End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD); Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL); Quality of Life (QoL)

INTRODUCTION

End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) is a serious, irreversible condition that affects a significant number of people worldwide. ESKD occurs when the estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR), is less than 10-15 ml/min/1.73m2. It causes significant biochemical abnormalities leading to symptom groups such as the uremic syndrome, pain, and fatigue that may impact negatively on an individual’s Quality of Life (QoL) [1]. Studies that measured the prevalence of symptoms in patients with ESKD reported that fatigue, pruritus, and pain were rated as the most distressing to ESKD patients.

The term ‘QoL’ is a multi-dimensional concept and can have several meanings [2], since several factors related to social and economic aspects must be considered when attempting to define the concept of QoL [3]. Several definitions are available in current literature that define the concept of QoL. With the existing numerous definitions of QoL, researchers, and clinicians, need to be clear about the conceptual definition of QoL so as not to confuse it with the disease process and complications or with treatment side effects.

To narrow and focus on the concept of QoL, the term Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) evolved to reflect the value of health states. HRQoL is determined by the way changes in health and treatment-related symptoms affect the dimensions of one’s wellbeing [4]. This description might indicate that HRQoL is entirely constructed by a patient’s individual perceptions and that others cannot make judgments about what is best for the patient. Patient perceptions about QoL have been found to have poor correlation with, and wide discrepancies between, practitioners’ assessments [5]. Health providers tend to overestimate or underestimate the effects of symptoms on a patient’s QoL. Although care providers believe that they know what patients want, patients’ feelings, preferences and perceptions cannot be assumed [6].

The aim of this narrative review is to analyze the conceptual and theoretical issues associated with QoL as well as the related concept of HRQoL and its measurement among patients experiencing ESKD.

METHODS

The search for articles relevant to this review was initiated by a comprehensive search using four electronic literature databases [SCOPUS, Cochran Library, Pro Quest (ASSIA) and EBSCO (CINAHL and Medline)]. The search also covered secondary internet resources (Science Direct and Pub Med), as well as non electronically published relevant articles to gain a full view of the relevant information published without specific dates. EBSCO, which consists of CINAHL and Medline, was the initial database accessed as it is known to contain regularly updated evidence-based healthcare literature. The literature search was not limited to any specific date in order to obtain the most applicable and relevant evidence. English was the only language used in the search because of the inability to interpret non-English published articles.

Both joined and separate keywords were used to find the published literature that discussed quality of life generally across all disciplines: “Quality of life” - “health related quality of life” - “integrative quality of life” - “QOL” or “QoL” - “QoL” or “HRQoL definition” - “QoL” or “HRQoL concept” or “HRQoL conceptualization” - “QoL” or “HRQoL theory” - “QoL” or “HRQoL operationalisation” - “End-Stage Kidney Disease”- “ESKD”. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in table 1.

|

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

|

1. Did not pertain to the QoL of humans 2. Published in a non-English language 3. Published as general information, dissertations, editorials and clinical opinions 4. Included a paediatric population |

Table 1: Shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data were retrieved from empirical studies and discussion articles and were extracted using relevant extraction methods. The results of the “empirical studies articles” were reported based on a modified data-extraction form suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI); whereas the results of the “discussion articles” were reported on three different themes (QoL definitions, conceptualization of QoL and theoretical factors) in a tabular form based on data-extraction tables using criteria suggested by Garrard’s (2007) Matrix Method. The Matrix Method is both a structure and a process for systematically reviewing literature.

Consistent with Garrard’s approach, the review matrix table, a place to record notes about papers using columns and rows, provides a standard structure for creating order. Each of the “discussion articles” was evaluated in ascending alphabetical order, using a structured abstracting form with seven columns: author’s name, publication year, country, paper type, paper purpose and context, participants (if any) and study findings (Appendix 1). The synthesis method employed in the Matrix Method is a critical-analysis and review process of the literature on a specific topic. Results were then tabulated and presented using the following headings: author and year of publication, country, design, sample size, outcome measures and key results.

RESULTS

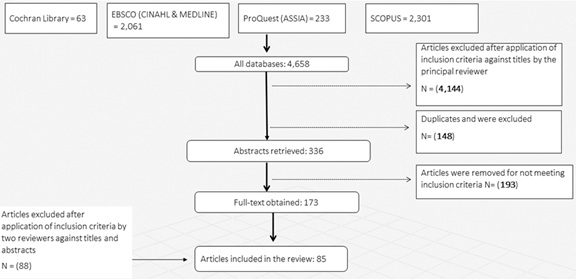

The inclusive search revealed a total of 4,658 articles. The identified articles were screened against titles in order to match inclusion and exclusion criteria, which then resulted in the exclusion of 4,144 articles. The remaining 514 articles were then checked for duplication using the End Note X4 reference management software program in which 148 articles were identified as duplicates and were excluded.

Checking the remaining articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria, 193 articles were removed for not meeting inclusion criteria, which left a remaining sum of 173 articles to be screened. Figures 1,2 shows the flow of literature identified.

Figure 1: Shows the flow of the identified literature after checking the remaining articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria, 193 articles were removed for not meeting inclusion criteria, which left a remaining sum of 173 articles to be screened.

Figure 1: Shows the flow of the identified literature after checking the remaining articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria, 193 articles were removed for not meeting inclusion criteria, which left a remaining sum of 173 articles to be screened.

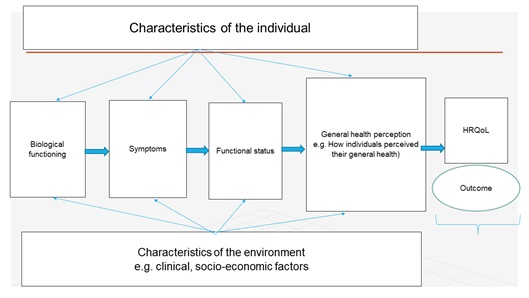

Figure 2: The revised version of the HRQoL outcomes.

Figure 2: The revised version of the HRQoL outcomes.

After excluding duplicate articles and those articles fitting the exclusion criteria (Appendix 2), two reviewers sorted out the list of the potential articles (173 articles) for inclusion independently by reviewing each article’s title and abstract. The aim was to maintain a rigorous selection process and minimize selection bias. A table was created to compare the ratings of both reviewers of articles to be included in the review that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Agreement between reviewers was reached in 70 articles. Disagreement occurred in 55 articles and on those occasions, a third researcher reviewed these further. This resulted in 85 full-text papers to be reviewed.

A final total of 85 articles met the inclusion criteria and are included in this narrative review: 27 empirical studies and 58 discussion articles (seven HRQoL; 18 concept analyses; 21 QoL definitions; and 12 papers related to different factors of QoL and HRQoL). The quality of the “empirical study papers” was assessed using the quality appraisal forms of the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) criteria; and for “discussion articles”, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist was used (Appendix 3.1 & 3.2).

DISCUSSION

The notion of QoL

Although the notion of QoL in nephrology started appearing in literature in the 1970s, it is often used to describe different physical and psychosocial variables including health status, functions, behaviours, life satisfaction, perceptions, and symptoms [7]. The term ‘QoL’ has been linked and used interchangeably with different related concepts such as ‘HRQoL’ and ‘functional ability’ [8]. The interchangeable use of the terms ‘health’, ‘functional ability’ and ‘QoL’, far from clarifying and providing exact meaning, might add additional confusion. In spite of inconsistency and the complexity of defining QoL, there is a consistency in literature that QoL is a multidimensional concept.

The majority of authors who conceptualize QoL have introduced the individual factor as a common criterion of QoL. Personal indicators describe individuals’ feelings about whether they are satisfied with their life and whether they feel good about things in general. It is believed that these indicators exist in the consciousness of an individual and identifying the importance of them to an individual can only be known by asking the person to state them [9]. Measuring personal factors, however, is difficult and is a subject that is always under debate due to its dynamic and individualised nature.

Most QoL researchers, however, suggest that the number of aspects of life is less important when compared with the ability to recognize and represent individual needs. This element should be reflected by QoL frameworks to recognize the need for a multi element framework and to realize that individuals know what is important to them. The essential characteristics of any set of life aspects is that they represent, in aggregate, the complete QoL construct [10]. Therefore, QoL aspects should be considered as the set of elements to which a variable is limited [11], or, in other words, the range over which the concept of QoL extends.

The concepts that researchers depend on when measuring QoL are not theory-based, or at the very minimum are not based on a tested conceptual model. QoL is composed of personal, health, as well as socio environmental, dimensions and these should be considered equally in any intended measurement of both concepts.

The relationship between QoL and health

There is an increased acceptance in the literature of using QoL as a critical endpoint in medical research. Yet, there is little consensus on how it differs from perceived health-status. The term ‘health’ is usually referred to as the absence of disease and illness, which might indicate a good level of quality of life on an individual level. Most of the measures of health status have considered health as a baseline for QoL [12]. However, a positive conception of health is difficult to measure due to the lack of agreement over its definition [13]. Also, it is difficult to determine if the state of health has been achieved because of the absence of a unified operational definition for the term ‘health’. Clinicians’ judgment might focus on the absence of disease, whereas other professionals, and indeed patients, might see it as the ability to carry out normal everyday tasks, feeling strong and fit to carry out life.

The WHO definition of ‘health’ as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being provided a new focus to the borders of the meaning of health rather than a narrow (disease-based) focus [14]. This step was followed by the development of measures of positive health. Currently, there is broad agreement that the concept of positive health is more than the absence of disease or even disability, but is about full functioning, efficiency of mind and body and social adjustment [15-17]. By reflecting on the concept of QoL, it can be realised that ‘health’ is a component of QoL with a kind of tautology and overlap existing between the concepts.

Health-related QoL

Because the majority of life domains are related to health, the term health-related quality of life ‘HRQoL’ is used to differentiate and specify health related issues from the general issues of quality of life. The term HRQoL was developed by psychological and sociological researchers primarily to help measure the health domains that influence an individual’s physical and mental health status [18]. HRQoL as a concept, therefore, is more appropriate in that it can be measured within distinct components which can be interpreted separately [19].

Both QoL and HRQoL concepts represent patients’ own satisfaction with life and can be influenced by how they perceive the physical, mental, and social effects of ESKD on their daily living [20,21]. This suggests that QoL and HRQoL are individualised concepts. That is, ESKD may be considered as an irritation for one patient but may be severely frustrating for others [22]. Studies that examined QoL and HRQoL in ESKD patients with different ethnicities and religious beliefs found significant differences in their perceptions about factors that make up their overall QoL [23-25]. Assessing QoL and HRQoL, therefore, using measures that are able to capture patients’ individualised experiences of health becomes a vital and often required part of health outcomes appraisal [26,27].

Measurement of HRQoL has the potential to provide important additional information about the wellbeing of individuals with ESKD which is not readily available from the clinical and laboratory assessments currently used to monitor patients [28]. Various measures are used with different languages, including Arabic Language, to assess HRQoL and its predictors, such as generic and disease-specific instruments. Generic measures are the ones most commonly used to evaluate different aspects of HRQoL: physical, psychological and social as well as perceived well-being; and disease or condition-specific measures which evaluate the particular symptom or condition that might be associated with level of QoL. Measuring such personal and complex theoretical concepts, therefore, is difficult, and, as a result, individualised QoL tools were developed. These tools allow respondents to nominate the areas of life which are most important, rate their level of functioning or satisfaction with each, and indicate the relative importance of each to their overall quality of life. However, there are very limited studies that have used a combination of generic QoL measures, disease-specific measures, and QoL individualised measures. This study has considered this gap in assessing QoL.

HRQoL and ESKD patients

The studies that examined QoL and HRQoL among ESKD patients revealed that patient’s life is affected due to major Co-morbidities, physical, mental, socioeconomic, and spiritual factors. Patients affected by ESKD have to receive dialysis for survival on a routine basis which creates uncertainty about their future, which may change their perception about their self and self-confidence, and sometimes bring about a reversal in family roles [29].

Co-morbidities such as malnutrition, anaemia, and Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) are strong determinant of HRQoL in individuals with ESKD. Hypoalbuminemia (albumin <35g/L) influenced physical composite summary negatively by affecting physical functioning and general health and emotional well-being [30]. Anaemia has also been shown to impact on HRQoL in persons with ESKD. Anaemia severity (haematocrit <33%) is associated with poor physical function, whereas the effect on social function was modest. A pre-existing myocardial infarction was the most common observed predictor of decline in HRQoL influencing physical role-functioning, general health and emotional role-functioning. Similarly, a history of Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) was associated with decline of HRQoL in ESKD patients [31].

Functional status, including physical functioning, role functioning, social functioning, and mental functioning as a result of disease symptoms and treatment regimens, is usually limited in patients with ESKD. Studies that have used physical performance, health, and self-reported measures reported low physical functioning in patients with ESKD [32-34]. Patients engaged in social activities reported better HRQoL, whereas social isolation and decreased social interactions were associated with worse HRQoL [3]. This might suggest that patients who develop an appropriate adaptive strategy to manage the stress stemming from the disease and subsequent HD treatment might able to maintain a better QoL [35-37].

Socio-demographic factors, such as gender, age, socioeconomic status, and marital status, correlate with HRQoL in ESKD patients. Female patients on HD consistently reported worse HRQoL when compared to men [31,38]. They had lower scores for physical functioning, emotional well-being, social function, and increased fatigue. Elderly patients also reported lower HRQoL in most of the HRQoL measures, particularly on physical functioning. Employment and marital status were associated positively with score of QoL and HRQoL [39]. Patients who were employed and were married or had a marriage-like relationship had higher mental health [40]. Similarly, patients who had a higher level of education associated with better HRQoL [41].

Spiritual aspect is the fourth determinant of HRQoL which can also be seen as a determinant of QoL. It refers to the affirmation of an individual’s life in relation to God, self and community [42]. It falls very much in line with one’s personal values, standards of conduct and the spiritual beliefs that shape one’s life. The importance of this aspect has often been noted in the literature. The emphasis in this aspect of life might be on the importance of spiritual aspect as a dimension that may help to organize an individual’s values so as to maintain a better QoL and HRQoL. This was highlighted by the literature that examined the influence of religiousness on HRQoL [43-45].

Religiosity is often understood as an individual’s involvement in a set of beliefs and social activities as a means of spiritual expression and this may include adherence to religious practices and traditions, such as Christmas, fasting during Ramadan, or adhering to specific dietary regimens such as avoiding alcohol and being vegetarian. The interplay between the two concepts of spirituality and religiosity may affect how individuals live and may also affect their moral decisions [44]. These consequently affect their day-to-day choices. In Islam, for instance, being religious is considered an essential element of happiness. Muslims perceive life satisfaction to be connected with (Allah’s or God’s) satisfaction through the dialogue and performance of worship, which results in the belief of having a pleasant and satisfied life [46].

Healthcare providers including nephrologists and nephrology nurses are encouraged to deal with patients from various ethnicities and cultures. Nephrologists and nephrology nurses are the centre of care for ESKD patients; thus, they should utilise cross cultural knowledge and culturally sensitive skills in providing and maximising good patient care outcomes. ESKD patients are close to the nephrology healthcare team because they spend around 15 hours each week in dialysis units attending dialysis session. Thus, the healthcare providers need to understand that HRQoL is important in improving renal care services and focus on the development and application of clear concepts that that look into psychosocial aspects of care, like emotional status, and social involvement.

Measures of QoL and HRQoL in ESKD patients

Three main approaches are used to assess QoL and HRQoL: Generic, disease specific and individualized measures. Many of the measures that have been developed are currently widely used and have been translated into different languages including Arabic. Generic instruments, sometimes referred to as health measures, for instance the Short Form-36 (SF36), attempt to measure a broad range of life aspects related to HRQoL. These measures cover a range of areas and can be used across different populations.

The perceived strength of these instruments is their ability to allow comparisons of outcomes to be made between the different groups measured [47]. Additionally, they provide the ability to monitor and screen large populations within different age spectrums. However, the use of such measures to assess impairment-specific populations, such as those people with chronic diseases, should be verified in order to ensure their appropriateness [48]. The success of these tools is likely to depend on group characteristics and these tools are more susceptible to the influence of general life factors other than illness severity, unlike measurement tools that are disease-specific.

The measures that are condition- or disease-specific are designed to address areas of life that are particularly pertinent for patients with a specific condition or disease in a predefined list of items which must be rated in a particular manner [49]. The limitations of this method of measurement lie in the difficulty of interpreting the responses and its relevance across different diseases. Despite these tools being criticized for having a narrow focus, they have been credited with being more sensitive to changes in health status compared with generic instruments [48]. Individualized measurement tools were developed as an attempt to explore the aspects of life that the individual perceives to be most important and to assess the level of functioning or satisfaction within each aspect [50].

A number of such measures have been developed, such as the Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life, based on direct weighting procedure (SEiQoL-DW), by McGee et al. [51] and O’Boyle et al. [52]; and the Quality of Life Index (QoLI) by Ferrans and Powers [53]. The main advantage of this type of measure of QoL is the ability to address individuals’ own concerns about their lives rather than impose standard questions which might be less relevant [44]. There are five main reasons for measuring QoL and HRQoL identified in the literature: (a) it provides an understanding of the causes and consequences of the difference in QoL and HRQoL among individuals and groups [18]; (b) it helps in assessing the impact of social and environmental factors on QoL and HRQoL [48,54]; (c) it estimates the needs of a target population; (d) it evaluates the effectiveness of health interventions and the quality of any healthcare system [55-57] and (e) it helps in forming clinical decisions [58]. Therefore, measuring overall QoL and HRQoL requires a formal and scientific rigor of assessment in its approach.

FUTURE DIRECTION

Future researchers who examine HRQoL should consider that the terms “QoL”, “life satisfaction”, “functional status” and “wellbeing” cannot be used interchangeably because this causes confusion for both the researcher and the participants whose perceptions they intend to measure. Cultural and language adaptations should also be considered, and more cross-cultural research is needed to examine the relationship between QoL and cultural effects. This might include using individualised QoL instruments to explore the meaning of QoL across cultures.

Healthcare providers including nephrologists and nephrology nurses are encouraged to deal with patients from various ethnicities and cultures. Nephrologists and nephrology nurses should utilise cross cultural knowledge and culturally sensitive skills in providing and maximising good patient care outcomes. They need to understand that HRQoL is important in improving renal care services and focus on the development and application of clear concepts that that look into psychosocial aspects of care, like emotional status, and social involvement.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The study required no approved by the Scientific Research Committee at the Royal Hospital, Muscat, Oman.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to the publication and to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Author contribution statement

All authors have contributed equally

Data availability statement

No data provided for this study.

Informed consent

No consent required for this study.

Funding

No funding available.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all our patients and staff for their trust on us.

REFERENCES

- Trivedi DD (2011) Palliative dialysis in end-stage renal disease. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 28: 539-542.

- Sousa P, Bazeley M, Johansson S, Wijk H (2006) The use of national registries data in three European countries in order to improve health care quality. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 19: 551-560.

- Kao TW, Lai MS, Tsai TJ, Jan CF, Chie WC, et al. (2009) Economic, social, and psychological factors associated with health-related quality of life of chronic hemodialysis patients in northern Taiwan: A multicenter study. Artif Organs 33: 61-68.

- Huber JG, Sillick J, Skarakis-Doyle E (2010) Personal perception and personal factors: Incorporating health-related quality of life into the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Disabil Rehabil 32: 1955-1965.

- Krethong P, Jirapaet V, Jitpanya C, Sloan R (2008) A causal model of health-related quality of life in Thai patients with heart-failure. J Nurs Scholarsh 40: 254-260.

- Painter P, Krasnoff JB, Kuskowski M, Frassetto L, Johansen K (2012) Effects of modality change on health-related quality of life. Hemodial Int 16: 377-386.

- Fink AM (2009) Toward a new definition of health disparity: A concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs 20: 349-357.

- Ebrahim SH, Gehrmann U, Wieseler B (2007) Reporting on health-related quality of life in Cochrane reviews - a challenge for authors?

- Pinto-Prades JL, Abellan-Perpinan JM (2005) Measuring the health of populations: the veil of ignorance approach. Health Econ 14: 69-82.

- Claes C, Van Hove G, Vandevelde S, van Loon J, Schalock R (2012) The influence of supports strategies, environmental factors, and client characteristics on quality of life-related personal outcomes. Res Dev Disabil 33: 96-103.

- Wiesmann U, Niehörster G, Hannich HJ, Hartmann U (2008) Dimensions and profiles of the generalized health-related self-concept. Br J Health Psychol 13: 755-771.

- Hall T, Krahn GL, Horner-Johnson W, Lamb G (2011) Examining functional content in widely used health-related quality of life scales. Rehabil Psychol 56: 94-99.

- Kurpas D, Mroczek B, Bielska D (2013) The correlation between quality of life, acceptance of illness and health behaviors of advanced age patients. Archives Of Gerontology And Geriatrics 56: 448-456.

- Holmes S (2005) Assessing the quality of life-reality or impossible dream? A discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud 42: 493-501.

- Fang J, Fleck MP, Green A, McVilly K, Hao Y, et al. (2011) The response scale for the intellectual disability module of the WHOQOL: 5-point or 3-point. J Intellect Disabil Res 55: 537-549.

- Kaasa S, Loge JH (2003) Quality of life in palliative care: Principles and practice. Palliat Med 17: 11-20.

- Krethong P, Jirapaet V, Jitpanya C, Sloan R (2008) A causal model of health-related quality of life in Thai patients with heart-failure. Journal Of Nursing Scholarship 40: 254-260.

- Cella D, Chang CH, Wright BD, Von Roenn JH, Skeel RT (2005) Defining higher order dimensions of self-reported health: Further evidence for a two-dimensional structure. Eval Health Prof 28: 122-141.

- Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR (2003) Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 56: 395-407.

- Griva K, Jayasena D, Davenport A, Harrison M, Newman SP (2009) Illness and treatment cognitions and health related quality of life in end stage renal disease. Br J Health Psychol 14: 17-34.

- Griva K, Kang AW, Yu ZL, Mooppil NK, Foo M, et al. (2014) Quality of life and emotional distress between patients on peritoneal dialysis versus community-based hemodialysis. Qual Life Res 23: 57-66.

- Ferrans CE (1996) Development of a conceptual model of quality of life. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 10: 293-304.

- Hallinen T, Soini EJ, Martikainen JA, Ikaheimo R, Ryynanen OP (2009) Costs and quality of life effects of the first year of renal replacement therapy in one Finnish treatment centre. J Med Econ 12: 136-140.

- Fukuhara S, Yamazaki S, Hayashino Y, Green J (2007) Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with end-stage renal disease: Why and how. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 3: 352-353.

- Abd ElHafeez S, Sallam SA, Gad ZM, Zoccali C, Torino C, et al. (2012) Cultural adaptation and validation of the "Kidney Disease and Quality of Life--Short Form (KDQOL-SF™) version 1.3" questionnaire in Egypt. BMC Nephrol 13: 170.

- Anderson JS, Ferrans CE (1997) The quality of life of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Nerv Ment Dis 185: 359-367.

- Anderson KL, Burckhardt CS (1999) Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life as an outcome variable for health care intervention and research. J Adv Nurs 29: 298-306.

- Soni RK, Weisbord SD, Unruh ML (2010) Health-related quality of life outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 153-159.

- George LW, Bearon LB (1980) Quality of life in older persons: Meaning and measurement. Human Sciences Press, New York, USA.

- Laws RA, Tapsell LC, Kelly J (2000) Nutritional status and its relationship to quality of life in a sample of chronic hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 10: 139-147.

- Mujais SK, Story K, Brouillette J, Takano T, Soroka S, et al. (2009) Health-related quality of life in CKD Patients: Correlates and evolution over time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1293-1301.

- Guney I, Atalay H, Solak Y, Altintepe L, Tonbul H, et al. (2012) Poor quality of life is associated with increased mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients: A prospective cohort study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 23: 493-499.

- Guney I, Atalay H, Solak Y, Altintepe L, Toy H, et al. (2010) Predictors of sleep quality in hemodialysis patients. Int J Artif Organs 33: 154-160.

- Morsch CM, Goncalves LF, Barros E (2006) Health-related quality of life among haemodialysis patients--relationship with clinical indicators, morbidity and mortality. J Clin Nurs 15: 498-504.

- Peruniak GS (2008) The promise of quality of life. Journal of Employment Counselling 45: 50-60.

- Skevington SM (2009) Conceptualising dimensions of quality of life in poverty. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 19: 33-50.

- Welsch H (2009) Implications of happiness research for environmental economics. Ecological Economics 68: 2735-2742.

- Loos C, Briancon S, Frimat L, Hanesse B, Kessler M (2003) Effect of end-stage renal disease on the quality of life of older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 51: 229-233.

- Oren B, Enc N (2013) Quality of life in chronic haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in Turkey and related factors. Int J Nurs Pract 19: 547-556.

- Bohlke M, Marini SS, Gomes RH, Terhorst L, Rocha M, et al. (2008) Predictors of employment after successful kidney transplantation-a population-based study. Clin Transplant 22: 405-410.

- Fagerlind H, Ring L, Brulde B, Feltelius N, Lindblad AK (2010) Patients' understanding of the concepts of health and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns 78: 104-110.

- Johnson ME, Piderman KM, Sloan JA, Huschka M, Atherton PJ, et al. (2007) Measuring spiritual quality of life in patients with cancer. J Support Oncol 5: 437-442.

- Ramirez SP, Macedo DS, Sales PM, Figueiredo SM, Daher EF, et al. (2012) The relationship between religious coping, psychological distress and quality of life in hemodialysis patients. J Psychosom Res 72: 129-135.

- Gall TL, Malette J, Guirguis-Younger M (2011) Spirituality and religiousness: A diversity of definitions. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 13: 158-181.

- WHOQOL SRPB Group (2006) A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Soc Sci Med 62: 1486-1497.

- Tayeb MA, Al-Zamel E, Fareed MM, Abouellail HA (2010) A "good death": perspectives of Muslim patients and health care providers. Ann Saudi Med 30: 215-221.

- Bowden A, Fox-Rushby JA (2003) A systematic and critical review of the process of translation and adaptation of generic health-related quality of life measures in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America. Soc Sci Med 57: 1289-1306.

- Hall T, Krahn GL, Horner-Johnson W, Lamb G, Rehabilitation Research and Training Center Expert Panel on Health Measurement (2011) Examining functional content in widely used health-related quality of life scales. Rehabil Psychol 56: 94-99.

- Bergland A, Narum I (2007) Quality of life: Diversity in content and meaning. Critical Reviews in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 19: 115-139.

- Tavernier SS, Totten AM, Beck SL (2011) Assessing content validity of the patient generated index using cognitive interviews. Qual Health Res 21: 1729-1738.

- McGee HM, O'Boyle CA, Hickey A, O'Malley K, Joyce CR (1991) Assessing the quality of life of the individual: The SEIQoL with a healthy and a gastroenterology unit population. Psychol Med 21: 749-759.

- Joyce C, O’boyle C, McGee H (1999) Individual quality of life: Approaches to conceptualisation and assessment. Taylor & Francis, Oxfordshire, UK.

- Ferrans CE, Powers MJ (1985) Quality of life index: Development and psychometric properties. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 8: 15-24.

- Bullinger M, Brütt AL, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U, BELLA Study Group (2008) Psychometric properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: Results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1: 125-132.

- Burckhardt CS, Anderson KL (2003) The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): Reliability, validity, and utilization. Health and quality of life outcomes 1: 60.

- Clark EH (2004) Quality of life: A basis for clinical decision-making in community psychiatric care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 11: 725-730.

- Chwalisz K (2008) The future of counselling psychology: Improving quality of life for persons with chronic health issues. The Counselling Psychologist 36: 98-107.

- Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R (2005) The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: Lack of impact or lack of theory? Soc Sci Med 60: 833-843.

APPENDIX

|

Author (year) |

Category |

Purpose and Context |

Participant Characteristics (if any) |

Main Findings and Limitations |

|

A concept analysis paper |

Purpose: To clarify the concept of QoL for further use. Context: Health care Setting: - Country: Canada |

- |

· A clarified definition of QoL is proposed, as “QoL is a feeling of overall life satisfaction, as determined by the mentally alert individual whose life is being evaluated”. · Individual’s living conditions should meet their basic life needs. · QoL both subjective and objective components. |

|

|

A concept analysis paper |

Purpose: To examine briefly the concept of QoL by using some philosophical thoughts, particularly those from Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). Context: Health care Setting: - Country: UK |

- |

· Authors believe that QoL concept is humanly-made arbitrary products. · Health care researchers should remain critical about the usage of QoL concepts and keep re-examining them. This study look at such topic with new perspectives which generate new insights. · Philosophy has a role to play in understanding some issues in health care research. |

|

|

A concept analysis paper |

Purpose: To analyse how the concept of QoL is currently being defined and used within health care. Context: Health care Setting: - Country: USA |

- |

· The analysis supports the theorists who advocate QoL’s comprising subjective and objective indicators. · Future efforts are required in developing an understanding of QoL to be directed towards two major areas: (a) the concepts of QoL must be further refined and opposing conceptual perspectives must be resolved; (b) the differentiation of QoL from closely related concepts such as well-being, life satisfaction, functional status and health status. |

|

|

Systematic review paper |

Purpose: (a) To identify the most frequently used HRQoL models and (b) critique those models Context: Health care Setting: - Country: USA

|

- |

· The most frequently used HRQoL models were: Wilson and Cleary (16%), Ferrans and Colleagues (4%), or WHO (5%). Ferrans and colleague’s model was a revision of Wilson and Cleary’s model and appeared to have the greatest potential to guide future HRQoL research and practice. · Search strategy were limited to selected databases (Pub Med, MEDLINE, CINAHL and Psych INFO) and limited time of 10 years. · Most of analysed articles were descriptive, correlational or literature reviews. |

|

|

A discussion paper |

Purpose: To summarise the current understanding of the construct of individual QoL (as spate from family or health related) as it pertains to persons with intellectual disabilities. Context: Health care Setting: - Country: USA

|

- |

· Currently, QoL is an important concept in service delivery principle, along with its current use and multidimensional nature. QoL researchers beginning to understand the importance of methodological pluralism in the assessment of QoL, the multiple uses of quality indicators, the predictors of assessed QoL, the effects of different data collection strategies and the etic (universal) and Emic (culture-bound) properties of the construct. Yet to understand fully the use of QoL-related outcomes in programme change, how to best evaluate the outcomes of QoL-related services. |

|

|

A discussion paper |

Purpose: To present an overview and critique of different conceptualisation of QoL, with the ultimate goal of making QoL a less ambiguous concept. Context: Health care Setting: - Country: Belgium |

- |

· Defining QoL in terms of life satisfaction is most appropriate because this definition successfully deals with all the conceptual problems discussed within this paper. · It is recommended that researchers and theorists can initiate conceptual debates with the aim of making QoL a less ambiguous concept. |

|

|

Literature review paper |

Purpose: To review literatures that could improve understanding about the relationship between conceptualisations of QoL and subjective well-being. Context: Health psychology Setting: - Country: UK |

- |

· The definition of subjective well-being derived by an expert panel displays high convergence with an international definition of QoL. · Cross-cultural evidence showed that subjective well-being and QoL contained a substantial component of life satisfaction. · Increased material resources (objective factors) do not directly lead to improvements in subjective well-being, however might influence some of subjective factors. · Social capital acts as a buffer to poor QoL and subjective well-being in poorer communities. |

|

|

|

Purpose: To compare QoL in individuals with server mental illness against a sample of the general population and to investigate the role of self-esteem, self-efficacy and social functioning. Context: Mental health

|

|

· Significant differences found between clinical and non-clinical groups in four domains of the QHOQOL-100 and in a majority of the aspects within domains. · Participants with mental illness have similar need to a normal population in terms of social support and social networks. · Some key variance exist between the samples in terms of age, employment, marital status and education. |

Appendix 1: Results of the articles analysed by QoL concept.

|

Study Title |

Reasons for Exclusion |

|

Abellan-Perpifian, J.-M. and J.-L. Pinto-Prades (2005). "Measuring the health of populations: the veil of ignorance approach." Health Economics 14(1): 69-82. |

Economical paper |

|

Acton, G. J. and P. Malathum (2000). "Basic Need Status and Health-Promoting Self-Care Behavior in Adults." Western Journal of Nursing Research 22(7): 796-811. |

Not related to QoL |

|

Ashby, M., et al. (2005). "Renal dialysis abatement: lessons from a social study." Palliative Medicine 19(5): 389-396. |

A summary article |

|

Bennett, K., et al. (1991) Methodologic challenges in the development of utility measures of health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. Controlled Clinical Trials 12, 118s-128s. |

Methodology paper |

|

Berger-Schmitt, R. (2002). "Considering social cohesion in quality of life assessments: concept and measurement." Social Indicators Research 58(1-3): 403-428. |

Focus on social cohesion |

|

Bonner, A. and J. Greenwood (2006). "The acquisition and exercise of nephrology nursing expertise: A grounded theory study." Journal of Clinical Nursing 15(4): 480-489. |

Focus on exercise |

|

Bournes, D. A. (2000). "Concept inventing: a process for creating a unitary definition of having courage." Nursing Science Quarterly 13(2): 143-149. |

Focus on courage concept |

|

Brander, P., et al. (2004). "Living with a terminal illness: patients' priorities." Journal of Advanced Nursing 45(6): 611-620. |

Not related to QoL |

|

Brazier, J. and M. Deverill (1999). "A checklist for judging preference-based measures of health related quality of life: learning from psychometrics." Health Economics 8(1): 41-51. |

Methodological study |

|

Brooks, N. (2000). "Quality of life and the high-dependency unit." Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 16(1): 18-32. |

Focus on high-dependency unit |

|

Brush, B. L., et al. (2011). "Overcoming: A Concept Analysis." Nursing Forum 46(3): 160-168. |

Methodological paper |

|

Bullinger, M., et al. (2008). "Psychometric properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: results of the BELLA study." European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 17(1): 125-132. |

Methodological study |

|

Burnes, B. and B. Cooke (2012). "Kurt Lewin's Field Theory: A Review and Re-evaluation." International Journal of Management Reviews. |

No abstracts |

|

Calvin, A. O. and L. R. Eriksen (2006). "Assessing advance care planning readiness in individuals with kidney failure." Nephrology Nursing Journal: Journal Of The American Nephrology Nurses' Association 33(2): 165-170. |

Not related to QoL |

|

Candow, D. G. (2011). "Sarcopenia: Current theories and the potential beneficial effect of creatine application strategies." Biogerontology 12(4): 273-281. |

No abstract |

|

Carlesso, L. C., et al. (2012). "Reflecting on whiplash associated disorder through a QoL lens: An option to advance practice and research." Disability and Rehabilitation 34(13): 1131-1139. |

No abstract |

|

Carvalho, A. F., et al. (2013). "The psychological defensive profile of hemodialysis patients and its relationship to health-related quality of life." The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease 201(7): 621-628. |

Focus on psychological defensive profile |

|

Cella, D., et al. (2005). "Defining higher order dimensions of self-reported health: further evidence for a two-dimensional structure." Evaluation & the Health Professions 28(2): 122-141. |

General review |

|

Chwalisz, K. (2008). "The Future of Counseling Psychology: Improving Quality of Life for Persons With Chronic Health Issues." The Counseling Psychologist 36(1): 98-107. |

Focus on counselling |

|

Cicerchia, A. (1996). "Indicators for the measurement of the quality of urban life. What is the appropriate territorial dimension?" Social Indicators Research 39(3): 321-358. |

Related to environment |

|

Claes, C., et al. (2012). "The influence of supports strategies, environmental factors, and client characteristics on quality of life-related personal outcomes." Research in Developmental Disabilities 33(1): 96-103. |

Focus on intellectual disability |

|

Clark, E. H. (2002). Quality of life: psychiatric nurses hearing the voices of individuals with severe mental illness, University of Maine. Ph.D.: 194 p. |

Focus on mental illness |

|

Corcoran, M. A. (2007). "Defining and Measuring Constructs." The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 61(1). |

Relevant to inclusion criteria |

|

Cote, I., et al. (2000) Health-related quality-of-life measurement in hypertension. A review of randomised controlled drug trials. Pharmacoeconomics 18, 435-450 |

Describes the instruments of HRQoL |

|

Crosby, R. D., et al. (2003) Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 56, 395-407 |

Clinical relevance |

|

Cudney, S., et al. (2003). "Management of chronic illness: voices of rural women." Journal of Advanced Nursing 44(6): 566-574. |

Focus on chronic illness management |

|

Curran, D., et al. (2002). "Analysing longitudinal continuous quality of life data with dropout." Statistical Methods in Medical Research 11(1): 5-23. |

Focus on statistical issues |

|

Debout, C. (2011). "The concept of quality of life in healthcare, a complex definition]." Soins: La Revue de Reference Infirmiere(759): 32-34. |

Relevant to inclusion criteria (article in French Language) |

|

Diener, E., et al. (2013). "Theory and Validity of Life Satisfaction Scales." Social Indicators Research 112(3): 497-527. |

Focus on satisfaction scale |

|

Dyess, S. M. (2011). "Faith: a concept analysis." Journal of Advanced Nursing 67(12): 2723-2731. |

Relevant to inclusion criteria |

|

Ebrahim, S. H., et al. (2007) Reporting on health-related quality of life in Cochrane reviews - a challenge for authors? [abstract]. XV Cochrane Colloquium; 2007 Oct 23-27; Sao Paulo, Brazil 116-117 |

Relevant to inclusion criteria (still under review) |

|

Eckersley, R. (2013). "Subjective Wellbeing: Telling Only Half the Story: A Commentary on Diener et al. (2012). Theory and Validity of Life Satisfaction Scales. Social Indicators Research." Social Indicators Research 112(3): 529-534. |

Commentary paper |

|

Fang, J., et al. (2011). "The response scale for the intellectual disability module of the WHOQOL: 5-point or 3-point." Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 55(6): 537-549. |

Focus on disability module |

|

Farsides, B. and R. J. Dunlop (2001). "Is there such a thing as a life not worth living? Measuring quality of life." British Medical Journal 322(7300): 1481-1483. |

Focus on termination of pregnancy |

|

Ferrin, J. M., et al. (2011). "Psychometric validation of the Multidimensional Acceptance of Loss Scale." Clinical Rehabilitation 25(2): 166-174. |

Focus on loss scale |

|

Fetherman, D. L., et al. (2011). "A pilot study of the application of the transtheoretical framework during strength training in older women." Journal of Women and Aging 23(1): 58-76. |

Focus on strength training |

|

Fink, A. M. (2009). "Toward a new definition of health disparity: a concept analysis." Journal of Transcultural Nursing 20(4): 349-357. |

Focus on health disparity |

|

Fleming, S. and D. S. Evans (2008). "The concept of spirituality: its role within health promotion practice in the Republic of Ireland." Spirituality & Health International 9(2): 79-89. |

Relevant to inclusion criteria |

|

Flynn, R., et al. (2005). "The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: lack of impact or lack of theory?" Social Science & Medicine 60(4): 833-843. |

Focus on clinical decision making |

|

Frankel, A. (2009). "Nurses' learning styles: promoting better integration of theory into practice." Nursing times 105(2): 24-27. |

Relevant to inclusion criteria |

|

Frisch, M. B. (2013). "Evidence-Based Well-Being/Positive Psychology Assessment and Intervention with Quality of Life Therapy and Coaching and the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI)." Social Indicators Research 114(2): 193-227. |

No sufficient data provided |

|

Gall, T. L., et al. (2011). "Spirituality and Religiousness: A Diversity of Definitions." Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 13(3): 158-181. |

Relevant to inclusion criteria |

|

Ghylin, K. M., et al. (2008). "Clarifying the dimensions of four concepts of quality." Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 9(1): 73-94. |

Focus on industry quality |

|

Gibson, B., et al. (2005). "Variation and change in the meaning of oral health related quality of life: a "grounded" systems approach." Social Science & Medicine 60(8): 1859-1868. |

Focus on oral health quality of life |

|

Gill, L., et al. (2010). "Transitional aged care and the patient's view of quality." Quality in Ageing & Older Adults 11(2): 5-18. |

Focus on health service quality |

|

Gillison, F. B., et al. (2006). "Relationships among adolescents' weight perceptions, exercise goals, exercise motivation, quality of life and leisure-time exercise behaviour: A self-determination theory approach." Health Education Research 21(6): 836-847. |

Focus on adolescent’s weight |

|

Giordano, G. N., et al. (2012). "Social capital and self-rated health – A study of temporal (causal) relationships." Social Science & Medicine 75(2): 340-348. |

Focus on social capital role |

|

González, A., et al. (2012). "Motivational and emotional profiles in university undergraduates: A self-determination theory perspective." Spanish Journal of Psychology 15(3): 1069-1080. |

No abstract |

|

Hagerty, M. R., et al. (2001). "Quality of life indexes for national policy: review for research." Social Indicators Research 55(1): 1-96. |

Focus on life indexes |

|

Hallinen, T., et al. (2009). "Costs and quality of life effects of the first year of renal replacement therapy in one Finnish treatment centre." Journal Of Medical Economics 12(2): 136-140. |

Focus on renal transplant |

|

Halvari, A. E. M., et al. (2013). "Oral health and dental well-being: Testing a self-determination theory framework." Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43(2): 275-292. |

Focus on oral heath |

|

Hanestad, B. R. (1996). "Nurses' perceptions of the content, relevance and usefulness of the quality of life concept in relation to nursing practice." Vardi Norden 16(1): 17-21. |

Not relevant to inclusion criteria |

|

Hawthorne, G. (2009). "Assessing utility where short measures are required: development of the short Assessment of Quality of Life-8 (AQoL-8) instrument." Value In Health: The Journal Of The International Society For Pharmacoeconomics And Outcomes Research 12(6): 948-957. |

Methodological paper |

|

Herbert, R. J., et al. (2009). "A systematic review of questionnaires measuring health-related empowerment." Research & Theory for Nursing Practice 23(2): 107-132. |

focus on health related empowerments |

|

Hiemstra, M., et al. (2012). "Smoking-specific communication and children's smoking onset: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour." Psychology and Health 27(9): 1100-1117. |

Focus on children population |

|

Holt, J. (2000). "Exploration of the concept of hope in the Dominican Republic." Journal of Advanced Nursing 32(5): 1116-1125. |

Focus on Dominican republic |

|

Ismael, S. T. (2002). "A PAR approach to quality of life: frame working health through participation." Social Indicators Research 60(1-3): 41-54. |

Focus on Canadian government health vision |

|

Jalowiec, A., et al. (2007). "Predictors of Perceived Coping Effectiveness in Patients Awaiting a Heart Transplant." Nursing Research 56(4): 260-268. |

Focus on predictors |

|

Johnson, M., et al. (2012). "Professional identity and nursing: Contemporary theoretical developments and future research challenges." International Nursing Review 59(4): 562-569. |

Focus on professional identity |

|

Johnson, M. E., et al. (2007). "Measuring spiritual quality of life in patients with cancer." Journal of Supportive Oncology 5(9): 437-442. |

Focus on spiritual domain |

|

Julkunen, J. and R. Ahlstrom (2006). "Hostility, Anger, and Sense of Coherence As Predictors of Heath-Related Quality of Life. Results of an ASCOT Substudy." Journal of Psychosomatic Research 61(1): 33-39. |

Focus on predictors |

|

Kaasa, S. and J. H. Loge (2003). "Quality of life in palliative care: principles and practice." Palliative Medicine 17(1): 11-20. |

Focus on principles and practice |

|

Kemmler, G., et al. (2010) A new approach to combining clinical relevance and statistical significance for evaluation of quality of life changes in the individual patient. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63, 171-179 |

Clinical relevance |

|

kritsonis, a. (2005). "comparison of change theories." International journal of scholarly academic intellectual diversity 8(1): 3-7. |

Focus on change theory |

|

Krueger, J. I., et al. (2013). "Comparisons in research and reasoning: Toward an integrative theory of social induction." New Ideas in Psychology 31(2): 73-86. |

No abstracts |

|

Lach, L. M., et al. (2006). "Health-related quality of life in youth with epilepsy: Theoretical framework for clinicians and researchers. Part I: The role of epilepsy and co-morbidity." Quality of Life Research 15(7): 1161-1171. |

Focus on youth population |

|

Lambiri, D., et al. (2007). "Quality of Life in the Economic and Urban Economic Literature." Social Indicators Research 84(1): 1-25. |

Focus on economic literature |

|

Lang, H.-C., et al. (2012). "Quality Of Life, Treatments, and Patients' Willingness to Pay for a Complete Remission of Cervical Cancer in Taiwan." Health Economics 21(10): 1217-1233. |

Focus on payment preferences |

|

La-Placa, V., et al. (2003). "Defining and using quality of life: a survey of health care professionals." Clinical Rehabilitation 17(8): 865-870. |

Focus on health care professionals |

|

Lasseter, J. A. (2009). "Chronic Fatigue: Tired of Being Tired." Home Health Care Management & Practice 22(1): 10-15. |

Focus on chronic fatigue |

|

Lemmens, K. M. M., et al. (2008). "Designing patient-related interventions in COPD care: Empirical test of a theoretical framework." Patient Education and Counseling 72(2): 223-231. |

Focus on interventions |

|

Leung, K.-f., et al. (2005). "Development and validation of the Chinese Quality of Life Instrument." Health And Quality Of Life Outcomes 3: 26-26. |

Methodological study |

|

Lindelöf, N., et al. (2012). "Experiences of a high-intensity functional exercise programme among older people dependent in activities of daily living." Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 28(4): 307-316. |

Focus on exercise programme |

|

Lopez, E. D. S., et al. (2005). "Quality-of-Life Concerns of African American Breast Cancer Survivors Within Rural North Carolina: Blending the Techniques of Photovoice and Grounded Theory." Qualitative Health Research 15(1): 99-115. |

Describe the blended photo voice method |

|

Mandhouj, O., et al. (2012). "French-language version of the World Health Organization quality of life spirituality, religiousness and personal beliefs instrument." Health And Quality Of Life Outcomes 10: 39-39. |

Non-English language |

|

Mann, M., et al. (1986). "OASIS: a new concept for promoting the quality of life for older adults." American Journal of Occupational Therapy 40(Nov 86): 784-786. |

Describes a programme located in stores for older people |

|

Mary, D.-W. (2011). "Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies." BMC Medicine: 39. |

Focus on conducting reviews |

|

Mehrez, A. and A. Gafni (1990). "Evaluating health related quality of life: an indifference curve interpretation for the time trade-off technique." Social Science and Medicine 31(1990): 1281-1283. |

Focus on trade-off technique |

|

Mellon, L., et al. (2013). "Factors influencing adherence among Irish haemodialysis patients." Patient Education and Counseling 92(1): 88-93. |

Focus on HD influencing technique |

|

Mitchell, G. J. (1990). "The lived experience of taking life day-by-day in later life: research guided by Parse's emergent method." Nursing Science Quarterly 3(1): 29-36. |

Focus on lived experience in later life |

|

Montpetit, M. A., et al. (2006). "Adaptive change in self-concept and well-being during conjugal loss in later life." International Journal of Aging & Human Development 63(3): 217-239. |

Focus on self-concept on conjugal loss |

|

Moreira-Almeida, A. and H. G. Koenig (2006). "Retaining the Meaning of the Words Religiousness and Spirituality: A Commentary on the WHOQOL SRPB Group's "A Cross-Cultural Study of Spirituality, Religion, and Personal Beliefs As Components of Quality of Life" (62: 6, 2005, 1486-1497)." Social Science & Medicine 63(4): 843-845. |

A commentary paper |

|

Mullaney, A. and G. Pinfield (1996). "No indication of quality or equity." Town and Country Planning 65(5): 132-133. |

Focus on equity |

|

Mystakidou, K., et al. (1999). "Quality of life as a parameter determining therapeutic choices in cancer care in a Greek sample." Palliative Medicine 13(5): 385-392. |

Focus on therapeutic choices |

|

Noll, H. H. (2002). "Towards a European system of social indicators: theoretical framework and system architecture." Social Indicators Research 58(1-3): 47-87. |

Focus on European system of social indicators |

|

O'Connell, K. A. and S. M. Skevington (2010). "Spiritual, religious, and personal beliefs are important and distinctive to assessing quality of life in health: A comparison of theoretical frameworks." British Journal of Health Psychology 15(4): 729-748. |

Theoretical comparison |

|

Painter, P., et al. (2012). "Effects of modality change on health-related quality of life." Hemodialysis International. International Symposium On Home Hemodialysis 16(3): 377-386. |

Focus on dialysis modality change on HRQOl |

|

Pastrana, T., et al. (2008). "A matter of definition - key elements identified in a discourse analysis of definitions of palliative care." Palliative Medicine 22(3): 222-232. |

Focus on palliative care |

|

Paterson, B. L., et al. (2001). "Critical analysis of self-care decision making in chronic illness." Journal of Advanced Nursing 35(3): 335-341. |

Focus on self-care decision making |

|

Patrick, D., et al. (2005) Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of quality of life outcomes: preliminary results and work in progress [abstract]. XIII Cochrane Colloquium; 2005 Oct 22-26; Melbourne, Australia 127 |

On-going study |

|

Perlman, R. L., et al. (2005). "Quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD): a cross-sectional analysis in the Renal Research Institute-CKD study." American Journal Of Kidney Diseases: The Official Journal Of The National Kidney Foundation 45(4): 658-666. |

Comparison study between dialysis treatment |

|

Peruniak, G. S. (2008). "The Promise of Quality of Life." Journal of Employment Counseling 45(2): 50-60. |

General paper |

|

Portillo, M. C. (2009). "Understanding the practical and theoretical development of social rehabilitation through action research." Journal of Clinical Nursing 18(2): 234-245. |

No sufficient information |

|

Read, J. L., et al. (1987) Measuring overall health: an evaluation of three important approaches. Journal of Chronic Diseases 40, 7s-26s |

General review paper |

|

Reininghaus, U. and S. Priebe (2012). "Measuring patient-reported outcomes in psychosis: conceptual and methodological review." The British Journal of Psychiatry 201(4): 262-267. |

Focus on outcome in psychosis |

|

Roberts, J. A. and A. Clement (2007). "Materialism And Satisfaction With Over-All Quality Of Life And Eight Life Domains." Social Indicators Research 82(1): 79-92. |

Focus on materialism and satisfaction |

|

Royuela, V. and J. Surinach (2005). "Constituents of Quality of Life and Urban Size." Social Indicators Research 74(3): 549-572. |

Focus on urban size |

|

Sartorius, N. (1995). "Rehabilitation and quality of life." International Journal of Mental Health 24(1): 7-13. |

Focus on rehabilitation |

|

Schunemann, H. J., et al. (2006) Interpreting the results of patient reported outcome measures in clinical trials: the clinician's perspective. Health And Quality Of Life Outcomes 4, 62 |

Focus on interpreting patient’s report |

|

Senzon, S. A. (1999). "Causation related to self-organization and health related quality of life expression based on the vertebral subluxation framework, the philosophy of chiropractic, and the new biology." Journal of Vertebral Subluxation Research (JVSR) 3(3): 1-9. |

Focus on causation related to self-organisation |

|

Shaw, C., et al. (2008). "How people decide to seek health care: A qualitative study." International Journal of Nursing Studies 45(10): 1516-524. |

Focus on service use |

|

Siegrist, J. (2001). "Stress, ageing and quality of life." European Review 9(4): 487-499. |

Focus on stress and aging |

|

Sirgy, M. J. (1998). "Materialism and quality of life." Social Indicators Research 43(3): 227-260. |

Focus on materialism |

|

Stuifbergen, A. K., et al. (1990). "Perceptions of health among adults with disabilities." Health Values: The Journal of Health Behavior, Education & Promotion 14(2): 18-26. |

Focus on health perception among disabilities |

|

Suh, E. E. (2004). "The framework of cultural competence through an evolutionary concept analysis." Journal of Transcultural Nursing 15(2): 93-102. |

Discussion paper |

|

Tayeb, M. A., et al. (2010). "A "good death": perspectives of Muslim patients health care providers." Annals of Saudi Medicine 30(3): 215-221. |

Focus on good death |

|

Taylor, C. L. C., et al. (2007). "A social comparison theory analysis of group composition and efficacy of cancer support group programs." Social Science & Medicine 65(2): 262-273. |

Focus on support group programme |

|

Thomé, B., et al. (2003). "Home care with regard to definition, care recipients, content and outcome: systematic literature review." Journal of Clinical Nursing 12(6): 860-872. |

Focus on definition of home care |

|

Twycross, R. G. (1987). "Quality before quantity - a note of caution." Palliative Medicine 1(1): 65-72. |

Focus on the aim of medicine from the cradle to grave |

|

Walker, H., et al. (2012). "Are they worth it? A systematic review of QOL instruments for use with mentally disordered offenders who have a diagnosis of psychosis." British Journal of Forensic Practice 14(4): 252-268. |

Focus on instrument specific to mental disorders |

|

Wan, C., et al. (2011). "Development and Validation of the General Module of the System of Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases and Its Comparison with SF-36." Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 42(1): 93-104. |

Methodological study/review two |

|

Wasserman, L. I., et al. (2002). "Concepts of rehabilitation and quality of life: their continuity and differences in modern approaches." International Journal of Mental Health 31(1): 24-37. |

Focus on rehabilitation concept in modern approach |

|

Weinert, C., et al. (2008). "Evolution of a Conceptual Framework for Adaptation to Chronic Illness." Journal of Nursing Scholarship 40(4): 364-372. |

Focus on evaluation of conceptual framework |

|

Wiesmann, U., et al. (2008). "Dimensions and profiles of the generalized health-related self-concept." British Journal of Health Psychology 13(Pt 4): 755-771. |

Focused on self-concept |

|

Wood, A. M., et al. (2010). "Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration." Clinical Psychology Review 30(7): 890-905. |

Focus on gratitude. |

|

Yin, M. S. (2013). "Fifteen years of grey system theory research: A historical review and bibliometric analysis." Expert Systems with Applications 40(7): 2767-2775. |

Discussion paper |

|

Young, Y., et al. (2009). "Can successful aging and chronic illness coexist in the same individual? A multidimensional concept of successful aging." Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 10(2): 87-92. |

Focus on aging concept |

Appendix 2: Shows the excluded articles with the reasons.

|

Author |

Country |

Methodology |

Results |

||

|

Design/Sampling Method |

Size and Characteristics of Sample |

Measure |

|||

|

Abdel-Kader et al (2009) |

USA |

Cross-sectional design |

151 patients undergoing peritoneal or haemodialysis. |

SEiQOL-DW |

Family and health were the most common domain for patients. No significant differences in SEiQOL-DW scores between subgroups. SEiQOL-DW scores correlated mental wellbeing (r= -.22, p <0.010). |

|

Bailey et al (2007) |

USA |

Cross-sectional |

332 psychology and business students from Baylor University |

Trait Hope Scale, and Quality of life Inventory (QOLI) |

The internal reliabilities of both scales were above 0.70. Alphas for the scales were: Hope scale= 0.79 and QOLI= 0.73. |

|

Fagerlind et al (2009) |

Sweden |

A phenomenograpic Qualitative design |

Semi structured interviews of 22 patients with rheumatoid arthritis |

Interviews analysed by using QSR NUD*IST VIVO |

Two concepts ‘being health’ and ‘being able to function normally’ overlapped with respondents understanding of QoL. |

|

Garratt et al (1993) |

UK |

Observational study, postal questionnaire to check if SF-36 is a suitable measure for routine use within the NHS. |

1700 patients with one of four conditions (low back pain, menorrhagia, suspected peptic ulcer, varicose veins) |

SF-36 |

The SF-36 satisfied rigorous psychometric criteria for validity and internal consistency. Internal consistency (0.55-0.78) Validity (factor analysis identified 5 relevant factors with eigenvalues 12.8 to 1.3 |

|

Huber et al (2010) |

USA |

Cross-sectional design |

278 women with HIV disease |

Chronic Illness Quality of Life Ladder (CIQOLL) |

All internal consistency alpha coefficients were (0.91-0.95). Inter-item correlations (r=0.30-0.70). |

|

Kerthong et al (2008) |

Thailand |

Cross-sectional design |

A stratified four-stage random sampling of 422 heart-failure patients |

Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Social Support Instrument; Cardiac Symptom Survey; the New York Heart Association functional classification system; and a 100-mm horizontal visual analogue scale of GHP. |

Wilson and Cleary’s HRQoL fit well with the empirical data (X2=19.87, df=13, p=0.10, GFI=0.99, and RMSEA=0.04). Symptom status was the most influential factor affecting HRQoL and social support was the least influential factor affecting HRQoL. |

|

Kurpas et al (2012) |

Poland |

Cross-sectional design |

131 advanced age patients with chronically ill primary care |

WHOQoL-bref |

Highest score was on social relationship (M= 12.38 ± 2.75) and lowest was in the psychological domain (M= 12.38 ± 2.66) |

|

Murphy H & Murphy E (2006) |

UK |

Comparative observational study |

104 participants 52 mental health service users 20 general population |

WHOQOL-100 |

Significant differences between the two groups in 4 domains of the WHOQoL (independence and social relationships t=12.150, p |

|

O’Boyle et al (1992) |

Ireland |

Prospective study (6 months) |

20 patients undergoing unilateral hip-replacement |

SEiQOL |

Health status significantly improved by hip replacement (p<0.001) |

|

Prince P & Gerber G (2001) |

Canada |

Qualitative study |

Convenience sample of 36 patients serious mental illness |

SEiQOL-DW |

The SEiQOL-DW well accepted measure. The SEiQOL-DW global index (69.04, SD=24.58) was correlated with the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) (20.97, SD= 8.33). |

|

Rao et al (2008) |

USA |

Cross-sectional design |

898 |

Functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) |

Subscale scores: Physical wellbeing: p<0.001 Social wellbeing: p<0.001 Emotional wellbeing: p<0.001 |

|

Rudolf & Priebe (1999) |

German |

Longitudinal study. Interview within the first three weeks of admission |

185 women (42 women with depression, 70 women with alcoholism, 73 women with Schizophrenia) |

SQOL |

Depressive women after admission express low SQOL ((sub-scale: anxiety/depression [r:-.40, p<0.05], activation [r:-.40, p<0.05], thought disorder [r: -.46, p<0.01] |

|

Saban et al (2007) |

USA |

Longitudinal one-group Pilot study |

57 patients undergoing elective lumber spinal surgery |

SF-36 |

HRQoL significantly improved postoperatively (t[56] = 6.45, p<.01). |

|

Seongkum et al (2008) |

Canada |

Qualitative design |

Convenience sample of 20 patients |

Interviews guided by a set of questions to standardise the content of interview |

Patient’s definition of QoL their active pursuit of happiness and relationships with others. Patient’s self-evaluation of QoL reflected their adopted perception to their changed clinical condition and their positive outlook. |

|

Soaban et al (2008) |

USA |

Prospective observational study |

322 veterans receiving HD |

SF-6D KDCS |

The SF-6D correlated .911 (p<.05), indicating 83% of the variance in the 7-subscales of KDCS measure. |

|

Souse K & Kwok O (2006) |

USA |

Cross-sectional |

917 HIV patients |

AIDS-specific symptoms scale |

The range of correlations (n=917) for the composites of each domain were: symptom status, 0.27-0.56; functional health, 0.77-0.97; general health perception, 0.81; and overall QoL, 0.70. |

|

Souse K & Williamson A (2003) |

USA |

Longitudinal design (3 years) |

99 patients were presenting to the emergency department |

SF-36 |

Symptom status is a key predictor of HRQoL. The baseline symptom status contributed 20.2% (p=0.001) of the variance explained the baseline physical score, and symptom status at follow-up 23.2% (p= 0.001). symptom status explained the variance in baseline and follow-up mental scores (9.8%, p= 0.001 and 29.2%, p= 0.001) |

|

Soyupek et al (2010) |

Turkey |

Cross-sectional design |

40 patients |

Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) |

Self-concept and QoL of these patients were lower (p<0.001). |

|

Sprangers et al (2002) |

Netherland |

Cross-sectional design |

217 consecutive cancer patients in the acute phase of their illness vs 192 disease free cancer patients |

Activities of Daily Living Scale |

Patient with cancer reported poorer QoL (p<0.001). |

|

Staniszewska et al (1999) |

UK |

Qualitative study |

25 ethnic group (15 Indian patients and 10 white patients) |

SF-36 |

No differences identified between the two groups. |

|

Staniszewska S (1999) |

UK |

Qualitative study |

Semi-structured interviews for 33 cardiac patients to explore the possibility of extending the evaluation of health by patient’s expectation concept. |

SF-36 |

Comparison of the content of patient expectations with the SF-36 found some overlap but indicated that patients seemed to adopt a broader approach to their health (internal consistency (0.82 and 0.88) |

|

Tavernier et al (2011) |

USA |

Qualitative design |

Cognitive interviewing to explore patients with cancer understanding of PGI (7 men and 8 women) |

PGI |

Interview data supported the content validity of the PGI in comprehensively defining and adequately sampling participant HRQoL as an individualised construct. |

|

Tokuda et al (2009) |

Japan |

Cohort study design |

3344 participants (53% women; median age 35 years) |

SF- 36 |

One factor was retained (eigenvalue, 4.65; variance proportion f0.58). All item response category characteristic curves satisfied the monotonicity assumption in accurate order with corresponding ordinal responses. |

|

Unruh et al (2003) |

USA |

Comparative study : self-administered vs interviewer-administered surveys in HD patients |

978 HD patients: N= 427 interview survey N= 551 self-administered |

KDQOL-SF |

The interviewer group: had higher scores on sales that measured role-physical, role-emotional and effects of kidney disease (p<0.001). |

|

Verdugo et al (2012) |

Spain |

Analyses of the relationship between eight core QoL domains and 34 articles contained in the Convection. (The concept of QoL and its role in enhancing human rights of persons with intellectual disability) |

- |

- |

There is a close relationship between the core QoL domains (independence, social interaction, and wellbeing) and the 34 articles contained in the Convection. Three strategies can be used to enhance human rights of persons with intellectual disability: employ person-centred planning, publish provider profiles and implement as system of support. |

|

Wu. A et al (2004) |

USA |

Prospective cohort study |

Baseline: 698 HD 230 PD I year: 452 HD 133 PD |

SF-36 |

Better HRQoL for PD patients (bodily pain, travel, diet restriction, and dialysis access [p<0.05]). At 1 year, SF-36 scores improved. HD patients had greater improvement in domains (physical functioning and general health perception). |

|

Zadeh K & Unruh M (2005) |

USA |

Cohort study |

10,030 dialysis patients |

KDQOL-SF |

Patients in the lowest quintile of physical score, the adjusted relative risk (RR) of death was 93% higher (RR= 1.93, p<0.001) and the risk of hospitalisation was 56% higher (RR= 1056, p<0.001). |

Appendix 3.1: Shows the summary and results of the empirical studies.

|

Author |

Criteria |

||||||

|

Yes = √ No = × Unclear = UN |

Yes = √ No = × Unclear = UN |

Yes = √ No = × Unclear = UN |

Yes = √ No = × Unclear = UN |

Yes = √ No = × Unclear = UN |

Yes = √ No = × Unclear = UN |

Yes = √ No = × Unclear = UN |

|

|

Is the source of opinion/discussion clearly identified? |

Does the source of the discussion/ opinion have standing in the field of expertise? |

Are the interests of patients/clients the central focus of the opinion? |

Is the discussion/ opinion’s basis in logic/experience clearly argued? |

Is the argument developed analytical? |

Is there reference to the extant literature/ evidence and any incongruence with it logically defended? |

Is the discussion/ opinion supported by peers? |

|

|

Anderson & Burckhardt (1998) |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Camfield & Skevington (2013) |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Carr& Higginson (2001) |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

Carr et al (2001) |

√ |

UN |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

UN |

|

Chung et al (1997) |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

× |

|

Cohen &Kimmet (2013) |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|