Relationship between Antioxidants and the Development of the Periodontal Disease

*Corresponding Author(s):

Rudrakshi CDepartment Of Periodontology, Krishnadevaraya College Of Dental Sciences & Hospital, Hunasamaranahalli, Bangalore, India

Tel:+91 94480 57407,

Email:drrudrakshi@rediffmail.com

Abstract

The role of oxidative stress linking the free radical damage at the cellular level causes premature aging, including periodontal disease. To overcome this, it is important to explore the role of host specifically with regard to antioxidant status along with conventional periodontal therapy. Periodontal counselling and supplementation may very well reduce inflammation and thereby enhance outcomes of conventional periodontal therapy. The purpose of this review is to summarize available research in the role of antioxidants as an adjunct to periodontal therapy.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease caused primarily by bacteria in dental plaque, affecting the supporting structures of the teeth. Specific periodontal pathogens such as the gram-negative anaerobic bacteria inhabiting within the sub-gingival plaque are associated with the progressive form of the disease. Although bacteria are the major etiological agents, the host immune response to these bacteria is of fundamental importance. Hence, it is evident that periodontitis is a multifactorial disease, affiliates with specific microorganisms, social and behavioral factors, genetic or epigenetic trait, all of which are modulated and controlled by the underlying immune and inflammatory responses of the host [1].

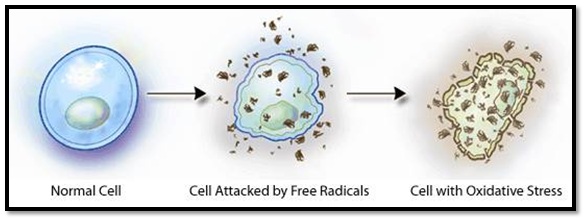

The recent focus on the progression of periodontitis is on the molecular aspects of host modulation. The discovery of the role of free radicals in chronic disease is as important as the discovery of the role of microorganism in inflammatory disease [2].

Free radicals & Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) production is an essential component of the host response for immune system, prostaglandin biosynthesis, anti-bacterial biosynthesis and variety of insults like trauma/burns [3]. Besides, the physiological system, ROS generation are induced by several exogenous factors such as pollution, smoke, radiation, pesticide and drug consumption. Major producers of ROS are mitochondrial cytochrome P-450 reactions, peroxisomal fatty acid metabolism and NADPH oxidase activity [4]. An imbalance between the ROS production and anti-oxidant mechanism leads to oxidative stress. Oxidative stress has been associated with both onset of periodontal destruction and systemic inflammation [5,6].

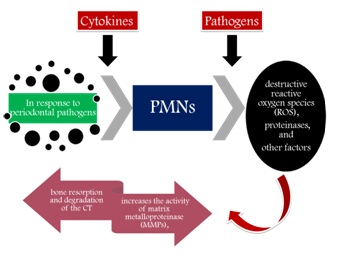

Primary immune response against periodontal pathogens is elevated numbers of neutrophils seen in connective tissue, junctional epithelium (50%) and gingival crevicular fluid (90%) and it can cause loss of epithelial cell-cell attachment in junctional epithelium (>60%) leading to apical shift of junctional epithelium [7].

Neutrophil have several mechanisms for controlling bacterial invasion which includes both intracellular and extracellular oxidative and non-oxidative killing mechanisms [8]. When neutrophils and macrophages get stimulated by a phagocytic stimulus, produces a ‘respiratory burst’, which is characterized by an increase in oxygen consumption, activation of the Hexose-Monophosphate (HMP) shunt and generation of Free Radicals (FR), Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and their metabolic products. At sites of chronic inflammation (periodontium in case of periodontitis), there is considerable over production of FR and reactive species.

Research with scientific evidence confirmed that inflammation in the oral tissues especially that associated with periodontitis can be a factor in chronic illness such as cardio and cerebro vascular diseases [9,10], diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, advance pregnancy outcomes and a growing list of other conditions such as cancer, psoriasis, chronic kidney disease and anemia. Several hypotheses proposed to describe the interlinking between periodontal diseases and systemic diseases. One of the explanations is imbalance between systemic oxidants and antioxidants [11-13]. “An antioxidant is any substance that, when present at low concentrations compared to those of an oxidizable substrate, significantly delays or prevents oxidation of that substrate” [14].

Hence the concept of inhibition of building up oxidative stress within cells through anti-oxidative therapy is implicated in inflammatory disorders and periodontitis along with gold standard therapy for periodontitis is through removal of subgingival biofilm through scaling and root planing has shown to be advantageous. The present article reviews on the comprehensive appraisal of the newer aspects of anti-oxidative therapy and it’s applications in Periodontology (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Role of polymorphopneutrophils.

Figure 1: Role of polymorphopneutrophils.

REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES (ROS)

| Free radicalsSources | Sources | |||

| Oxygen derived free radical | Non- Oxygen derived free radical | Exogenous | Endogenous(byproducts) | |

| Metabolism | Function | |||

| Superoxide (O2-)Hydroxyl (OH-)Hydroperoxyl (HOO)Alkoxyl (RO)Aryloxyl (ArO)Arylperoxyl (ArOO)Peroxyl ROOAcyloxyl (RCOO)Acylperoxyl (RCOOO) | Singlet oxygen (1O?)Ozone (O3)Hypochlorous acid (HOCl)Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | Heat, Trauma,Ultrasound,Ultraviolet light, Ozone, Smoking,Exhaust Fumes,Radiation, Infection,Excessive Exercise,Therapeutic Drugs | cell metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation(electrons transport chain) | By Osteoclasts atruffled borderduring boneresorption. Oxidative pathway ofphagocytosis by neutrophils and other phagocytes. |

| ROS (Mainly Hydroxyl and peroxynitrate anion) | Target molecule | Example | Effects |

| Protein | Gingival hyaluronic acidand Proteoglycans | · Folding/unfolding, Fragmentation· Protease degradation of the modified protein· Formation of protein radicals and protein bond ROS· polymerization of proteins· Formation of stable end products (acetaldehydes) | |

| Lipid | Cell membrane (activation of cyclooxygenases and lipo-oxygenases pathways) | · Peroxidation and formation of products these are bioactive molecules, Conjugated dienes· Lipid Proxides, Aldehydes· Volatile-hydrocarbons, Prostaglandin-E2(PG-E2) productioneg: Malondialdehyde, Acrolein, Isoprostanes and Neuroprostanes | |

| DNA | · Strand breaks, Base pair mutations, Deletions, Insertions, conversion of guanine to 8- hydroxyguanine,· Nicking and Sequence amplifications. | ||

| Activatingnuclear factor kB (NFkB) | Stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine release by monocytes and macrophages | ||

| Enzymes | Antiproteases such as α-1antitrypsin | Oxidation | |

| Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide | Cells | Osteoclast activation | Bone resorption |

Halliwell established 4 criteria for causal relationship between ROS and disease [18]

1. ROS or the oxidative damage caused must be present at the site of injury.

2. The time course of ROS formation or the oxidative damage caused should occur before or at the same time as tissue injury.

3. Direct application of ROS over a relevant time course to tissues at concentrations found in vivo should reproduce damage similar to that observed in the diseased tissue.

4. Removing or inhibiting ROS formation should decrease tissue damage to an extent related to their antioxidant action in vivo.

Growing evidence exist in causal relationship between oxidative stress and periodontitis [19] (Table 3).

| Targeted Periodontal tissue | Reaction of ROS | Effect |

| Ground substance | Depolymerization and Degradation (non-sulfated Glycosaminoglycans are more susceptible than sulfated) | All these events leads to periodontal tissue destruction (Figure 2) and alveolar bone resorption |

| Collagen | Collagenolysis | |

| Monocytes and macrophages | Stimulation of excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine | |

| lipid peroxidation | PG-E2 production leads to bone resorption |

Evidence suggesting causal relationship between ROS and periodontitis

Chapple and Matthews postulated that periodontal tissue destruction results in increased production of ROS and increased ratio between elastase and lactoferrin by peripheral neutrophils [5].

Agnihotri have been reported that increased levels of ROS in smokers was responsible for excessive periodontal tissue destruction [21].

Patil et al., have reported that the severity of tissue destruction due to excessive ROS is more when periodontal disease is associated with type 2 DM, indicating that oxidative stress is common factor involved in tissue destruction [22].

Di Meo et al., suggested that low levels of ROS are beneficial, but excessive generation or antioxidant deficiency results in periodontal tissue destruction [23].

Liu et al., He et al., have shown the potential link between ROS and autophagy in periodontitis [16,24].

ANTIOXIDANTS (AO)

| Sl.no | Based on | Examples |

| 1 | Mode of action | |

| Preventive | Suppress the formation of free radicals: catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and serum transferase | |

| Metal ion sequestrators: albumin, lactoferrin, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, uric acid, and Polyphenolic flavenoids | ||

| Quenching of active oxygen: superoxide dismutase and Carotenoids | ||

| Scavenging (Chain breaking) | Ascorbate, Carotenoids, uric acid, vitamin E, bilirubin, reduced glutathione & other | |

| 2 | Location | |

| Intracellular | Superoxide dismutase enzymes-1& 2, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, DNA repair enzymes & reduced glutathione. | |

| Extracellular | Superoxide dismutase enzyme-3, selenium glutathione peroxidase, reduced glutathuione, | |

| Membraneassociated | α-tocopherol | |

| 3 | Solubility | |

| Water soluble | Haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin, albumin, ascorbic acid, uric acid, Albumin, Polyphenolic flavenoids, reduced glutathione & other thiols, cysteine & transferrins | |

| Lipid soluble | α-tocopherol, Carotenoids, bilirubin, Ubiquinol and Vitamin A | |

| 4 | Repair De novo enzymes | DNA repair enzymes, Protease, Lipase and Transferase |

| 5 | Structures they protect | |

| DNA protectiveantioxidants | Superoxide dismutase enzymes 1 and 2, glutathione peroxidase, DNA repair enzymes [e.g. poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase], reduced glutathione, cysteine | |

| Protein-protectiveantioxidants | Sequestration of transition metals by preventative antioxidants, antioxidant enzymes | |

| Lipid-protectiveantioxidants | a-Tocopherol (vitamin E), ascorbate (vitamin C), carotenoids (including retinol - vitamin A), reduced ubiquinone, reduced glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, bilirubin | |

| 6 | By their origin | |

| Exogenous antioxidants | Carotenoids, ascorbic acid, tocopherols (a, b, c, d), polyphenols (e.g. flavenoids, catechins such as epigallocatechin-gallate), folic acid, cysteine | |

| Endogenous antioxidants | Catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione-S-transferase,reduced glutathione, ceruloplasmin, transferrin, ferritin, glycosylases, peroxisomes, proteases | |

| Synthetic | N-acetylcysteine, penicillinamine, tetracyclines | |

Table 4: Anti-oxidant classification.

Antioxidant enriched diet and periodontal diseases [25]

Green Tea

• Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (59%)

• Epigallocatechin (19%)

• Epicatechin-3-gallate (13.6%)

• Epicatechin

Local drug delivery of green tea extract has also shown promising results in treating periodontal diseases [27]. Dentifrice and mouthwashes can be contemplated as vehicles for self-application of chemotherapeutics. Recently, the addition of green tea catechins to dentifrice has shown reduction of periodontal inflammation in the rat model, by decreasing gingival oxidative stress and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [28].

Hrishi et al., conducted a study to evaluate the effect of adjunctive use of green tea dentifrice in periodontitis patients and concluded that green tea dentrifice may serve as a beneficial adjunct to non-surgical periodontal therapy as it showed greater reduction of gingival inflammation and improved periodontal parameters on comparison with fluoride-triclosan dentrifice [29].

Grape Seed Extracts (GSE)

Ozden FO et al., investigated the effects of GSE application on periodontium before and after ligature induced experimental periodontitis [34], using histological and immunohistochemical analyses. Histopathological findings showed improvements in the inhibition of periodontal inflammation and destruction following GSE intake.

Bark Extracts

Magnolol has been reported to have a potent anti-inflammatory activity via inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine, ROS formation, iNOS, COX-2 expression, and nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) activation, a key transcription factor regulating inflammation, in LPS-induced inflammatory disease [36,37]. Furthermore, magnolol exerts a marked antimicrobial activity against periodontopathic bacteria and activates osteoblast function [38]. Magnolol may be used as a potential candidate for treating periodontitis.

Lu SH et al., concluded in their study that magnolol significantly ameliorates the alveolar bone loss in ligature-induced experimental periodontitis by suppressing periodontopathic microorganism accumulation [39], NF-????B-mediated inflammatory mediator synthesis, RANKL formation, and osteoclastogenesis. These activities support that magnolol is a potential agent to treat periodontal disease.

Melatonin

Local and systemic administration of melatonin in rats with lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis reduced the level of enzymes (such as serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase and blood urea nitrogen) significantly compared with rats in the control group [42,44]. Similarly, locally administered melatonin significantly reduced bone resorption compared with rats receiving no treatment. These studies suggested that topical administration of melatonin can be used as an adjunct to conventional treatment protocols such as scaling, root planing, and surgical debridement to improve the outcomes of periodontal therapy.

Propolis Extract

A number of studies have presented evidence that propolis has strong hepatoprotective, antitumor, antioxidative, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Coutinho A in the year 2012 in their clinical study demonstrated the benefits provided by propolis extract and indicated that it should be considered for use as an adjuvant to scaling and root planing [45-48].

Salivary Antioxidant Status

Antioxidant status in gingival crevicular fluid

Significantly more intense levels of superoxide dismutases in gingival crevicular fluid comprise the most important antioxidant enzyme defense system against reactive oxygen species.

The reduced and oxidised glutathione concentrations in the gingival crevicular fluid are significantly lower in patients with chronic periodontitis, supporting that the glutathione levels in gingival crevicular fluid can play an important role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis [54].

Total antioxidant capacity

• Spectrophotometric assay

• Enhanced chemiluminescence assay

• Cyclic voltammetry assay

Salivary TAC decreases or does not changes in periodontal disease.

MECHANISM OF ACTION: [5,15]

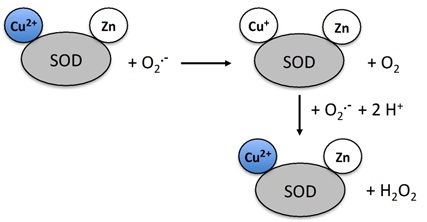

Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

Figure 3: Mechanism of action of superoxide dismutase.

Figure 3: Mechanism of action of superoxide dismutase.In humans SOD exists in 3 forms (Figures 4 and 5)

• Cytosolic Cu/Zn-SOD,

• Mitochondrial Mn-SOD (major role)

• Extracellular SOD (EC-SOD)

Figure 4: Mitrochondrial SOD.

Figure 4: Mitrochondrial SOD. Figure 5: Cytosolic Cu/Zn-SOD.

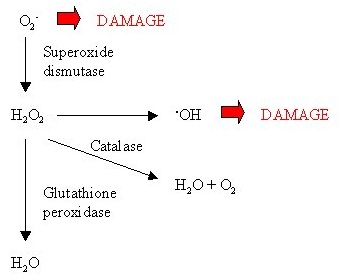

Figure 5: Cytosolic Cu/Zn-SOD.Catalase (CAT)

Figure 6: Role of catalase.

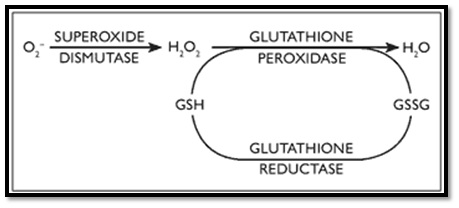

Figure 6: Role of catalase. Figure 7: Role of glutathione.

Figure 7: Role of glutathione.Uric acid

Ascorbic acid (vitamin C)

CONCLUSION

Following conclusion can be drawn with respect to the role of reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in periodontitis

1. Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species appear to play a significant role in the patho-physiology of periodontal diseases.

2. Adjunctive use of antioxidants with traditional therapies should be considered to improve the periodontal treatment outcome.

3. This review presents with evidence within the biomedical literature, provides exciting new opportunities for future development of host modulation therapies in periodontology.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

The results of the review may have relevance for the development of treatment protocols. The impact of the combination of periodontal therapy with antioxidants in terms of antioxidant/oxidative stress parameters requires further investigation with longer follow.

REFERENCES

- Lamster IB, Novak MJ (1992) Host mediators in gingival crevicular fluid: Implications for the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Crit Rev Oral Bio Med 3: 31-60.

- Bray TM (1999) Antioxidants and Oxidative Stress in Health and Disease: Introduction. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 222: 195.

- Pham-Huy LA, He H, Pham-Huy C (2008) Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci 4: 89-96.

- Downey GP, Fukushima T, Fialkow L (1995) Signaling mechanisms in human neutrophils. Curr Opin Hematol 2: 76-88.

- Chapple IL, Matthews JB (2007) The role of reactive oxygen and antioxidant species in periodontal tissue destruction. Periodontol 2000 43: 160-232.

- Basu S, Helmersson J, Jarosinska D, Sällsten G, Mazzolai B, et al. (2009) Regulatory factors of basal F(2)-isoprostane formation: population, age, gender and smoking habits in humans. Free Radic Res 43: 85-91.

- Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE (2014) Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000 64: 57-80.

- Dennison DK, Van Dyke TE (1997) The acute inflammatory response and the role of phagocytic cells in periodontal health and disease. Periodontol 2000 14: 54-78.

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Slade GD, Thornton-Evans GO, et al. (2015) Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol 86: 611-622.

- Engebretson S, Kocher T (2013) Evidence that periodontal treatment improves diabetes outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 40: 153-163.

- Jin LJ, Lamster IB, Greenspan JS, Pitts NB, Scully C, et al. (2016) Global burden of oral diseases: Emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis 22: 609-619.

- Buset SL, Walter C, Friedmann A, Weiger R, Borgnakke WS, et al. (2016) Are periodontal diseases really silent? A systematic review of their effect on quality of life. J Clin Periodontol 43: 333-344.

- Jeffcoat MK, Jeffcoat RL, Gladowski PA, Bramson JB, Blum JJ (2014) Impact of periodontal therapy on general health: Evidence from insurance data for five systemic conditions. Am J Prev Med 47: 166-174.

- Halliwell B (1997) Antioxidants: The basics--what they are and how to evaluate them. Adv Pharmacol 38: 3-20.

- Sree SL, Mythili R (2011) Antioxidants in Periodontal Diseases?: A Review. Indian J Multidiscip Dent 1: 140-146.

- Chengcheng Liu, Longyi Mo, Yulong Niu, Xin Li, Xuedong Zhou, et al. (2017) The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and Autophagy in Periodontitis and Their Potential Linkage. Front Physiol 8: 439.

- Dahiya P, Kamal R, Gupta R, Bhardwaj R, Chaudhary K, et al. (2013) Reactive oxygen species in periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol 17: 411-416.

- Halliwell B (1989) Free radicals, reactive oxygen species and human disease: A critical evaluation with special reference to atherosclerosis. Br J Exp Pathol 70: 737-757.

- Pendyala G, Thomas B, Kumari S (2008) The challenge of antioxidants to free radicals in periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol 12: 79-83.

- Sharma A, Wati S, Sharma S (2011) Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in periodontics?: A Review. Int J Dent Clin 3: 44-47.

- Agnihotri R, Pandurang P, Kamath SU, Goyal R, Ballal S, et al. (2009) Association of cigarette smoking with superoxide dismutase enzyme levels in subjects with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 80: 657-662.

- Patil VS, Patil VP, Gokhale N, Acharya A, Kangokar P (2016) Chronic Periodontitis in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Oxidative Stress as a Common Factor in Periodontal Tissue Injury. J Clin Diagn Res 10: 12-16.

- Di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P, Victor VM (2016) Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016: 1245049.

- He ZJ, Zhu FY, Li SS, Zhong L, Tan HY, et al. (2017) Inhibiting ROS-NF-κB-dependent autophagy enhanced brazilin-induced apoptosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Food Chem Toxicol 101: 55-66.

- Muniz FW, Nogueira SB, Mendes FL, Rösing CK, Moreira MM, et al. (2015) The impact of antioxidant agents complimentary to periodontal therapy on oxidative stress and periodontal outcomes: A systematic review. Arch Oral Biol 60: 1203-1214.

- Galli C, Passeri G, Macaluso GM (2011) FoxOs, Wnts and oxidative stress-induced bone loss: new players in the periodontitis arena? J Periodontal Res 46: 397-406.

- Hirasawa M, Takada K, Makimura M, Otake S (2002) Improvement of periodontal status by green tea catechin using a local delivery system: a clinical pilot study. J Periodontal Res 37: 433-438.

- Kudva P, Tabasum ST, Shekhawat NK (2011) Effect of green tea catechin, a local drug delivery system as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis patients: A clinicomicrobiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol 15: 39-45.

- Hrishi TS, Kundapur PP, Naha A, Thomas BS, Kamath S, et al. (2016) Effect of adjunctive use of green tea dentifrice in periodontitis patients - A randomized controlled pilot study. Int J Dent Hyg 14: 178-183.

- Baydar NG, Sagdic O, Ozkan G, Cetin S (2006) Determination of antibacterial effects and total phenolic contents of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) seed extracts. Int J Food Sci Tech 41: 799-804.

- Zhang XY, Bai DC, Wu YJ, Li WG, Liu NF (2005) Proanthocyanidin from grape seeds enhances anti-tumor effect of doxorubicin both in vitro and in vivo. Pharmazie 60: 533-538.

- Park JS, Park MK, Oh HJ, Woo YJ, Lim MA, et al. (2012) Grape-seed proanthocyanidin extract as suppressors of bone destruction in inflammatory autoimmune arthritis. PLoS One 7: 51377.

- Ahmad SF, Zoheir KM, Abdel-Hamied HE, Attia SM, Bakheet SA, et al. (2014) Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract protects against carrageenan-induced lung inflammation in mice through reduction of pro-inflammatory markers and chemokine expressions. Inflammation 37: 500-511.

- Özden FO, Sakallio?lu EE, Sakallio?lu U, Ayas B, Eri?gin Z (2017) Effects of grape seed extract on periodontal disease: an experimental study in rats. J Appl Oral Sci 25: 121-129.

- Shen JL, Man KM, Huang PH, Chen WC, Chen DC, et al. (2010) Honokiol and magnolol as multifunctional antioxidative molecules for dermatologic disorders. Molecules 15: 6452-6465.

- Yang TC, Zhang SW, Sun LN, Wang H, Ren AM (2008) Magnolol attenuates sepsis-induced gastrointestinal dysmotility in rats by modulating inflammatory mediators. World J Gastroenterol 14: 7353-7360.

- Tsai YC, Cheng PY, Kung CW, Peng YJ, Ke TH, et al. (2010) Beneficial effects of magnolol in a rodent model of endotoxin shock. Eur J Pharmacol 641: 67-73.

- Kwak EJ, Lee YS, Choi EM (2012) Effect of Magnolol on the Function of Osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 Cells. Mediators of Inflammation 2012: 829650.

- Lu SH, Huang RY, Chou TC (2013) Magnolol ameliorates ligature-induced periodontitis in rats and osteoclastogenesis: In vivo and in vitro study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013: 634095.

- Menendez-Pelaez A, Poeggeler B, Reiter RJ, Barlow-Walden L, Pablos MI, et al. (1993) Nuclear localization of melatonin in different mammalian tissues: Immunocytochemical and radioimmunoassay evidence. J Cell Biochem 53: 373-382.

- Kara A, Akman S, Ozkanlar S, Tozoglu U, Kalkan Y, et al. (2013) Immune modulatory and antioxidant effects of melatonin in experimental periodontitis in rats. Free Radic Biol Med 55: 21-26.

- Arabac? T, Kermen E, Özkanlar S, Köse O, Kara A, et al. (2015) Therapeutic effects of melatonin on alveolar bone resorption after experimental periodontitis in rats: A biochemical and immunohistochemical study. J Periodontol 86: 874-881.

- Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Konturek SJ, Loster B, Wisniewska G, Majewski S (2007) Melatonin and its role in oxidative stress related diseases of oral cavity. J Physiol Pharmacol 58: 5-19.

- Gulle K, Akpolat M, Kurcer Z, Cengiz MI, Baba F, et al. (2014) Multi-organ injuries caused by lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontal inflammation in rats: role of melatonin. J Periodontal Res 49: 736-741.

- Banskota AH, Tezuka Y, Kadota S (2001) Recent progress in pharmacological research of propolis. Phytother Res 15: 561-571.

- Sforcin JM (2007) Propolis and immune system: A review. J Ethnopharmacol 113: 1-14.

- Martos VM, Navajas RY, Fernandez LJ, Alvarez JA (2008) Functional properties of honey, propolis, and royal jelly. J Food Sci 73: 117-124.

- Coutinho A (2012) Honeybee propolis extract in periodontal treatment: a clinical and microbiological study of propolis in periodontal treatment. Indian J Dent Res 23: 294.

- Phaniendra A, Jestadi DB, Periyasamy L (2015) Free radicals: Properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J Clin Biochem 30: 11-26.

- Moore S, Calder KA, Miller NJ, Rice-Evans CA (1994) Antioxidant activity of saliva and periodontal disease. Free Radic Res 21: 417-425.

- Lynch E, Sheerin A, Claxon AW, Atherton MD, Rhodes CJ, et al. (1997) Multicomponent spectroscopic investigations of salivary antioxidant consumption by an oral rinse preparation containing the stable free radical species chlorine dioxide (ClO2.). Free Radic Res 26: 209-234.

- Chapple IL (1997) Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Periodontol 24: 287-296.

- Chapple ILC, Brock G, Eftimiadi C, Matthews JB (2002) Glutathione in gingival crevicular fluid and its relation to local antioxidant capacity in periodontal health and disease. Mol Pathol 55: 367-373.

- Öngöz DF, Bozkurt DS, Balli U, Avci B, Durmu?lar MC, et al. (2016) Glutathione levels in plasma, saliva and gingival crevicular fluid after periodontal therapy in obese and normal weight individuals. J Periodont Res 51: 726-734.

- Kusano C, Ferrari B (2008) Total Antioxidant Capacity: A biomarker in biomedical and nutritional studies. J Mol Cell Biol 7: 1-15.

- Diab-Ladki R, Pellat B, Chahine R (2003) Decrease in the total antioxidant activity of saliva in patients with periodontal diseases. Clin Oral Investig 7: 103-107.

- Dziegiel MH, Nielsen LK, Berkowicz A (2006) Detecting fetomaternal hemorrhage by flow cytometry. Curr Opin Hematol 13: 490-495.

- Kecskes Z (2003) Large fetomaternal hemorrhage: clinical presentation and outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 13:128-132.

- Zuppa AA, Scorrano A, Cota F, D’Andrea V, Francciolla A, et al. (2008) Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage and late-onset neutropenia: description of two cases. Turk J Pediatr 50: 400-404.

- Solomonia N, Playforth K, Reynolds EW (2012) Fetal-Maternal Hemorrhage: A Case and Literature Review. AJP Rep 2: 7-14.

- Dziegiel MH, Nielsen LK, Berkowicz A (2006) Detecting fetomaternal hemorrhage by flow cytometry. Curr Opin Hematol 13: 490-495.

- Kecskes Z (2003) Large fetomaternal hemorrhage: clinical presentation and outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 13:128-132.

- Zuppa AA, Scorrano A, Cota F, D’Andrea V, Francciolla A, et al. (2008) Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage and late-onset neutropenia: description of two cases. Turk J Pediatr 50: 400-404.

- Solomonia N, Playforth K, Reynolds EW (2012) Fetal-Maternal Hemorrhage: A Case and Literature Review. AJP Rep 2: 7-14.

- Dziegiel MH, Nielsen LK, Berkowicz A (2006) Detecting fetomaternal hemorrhage by flow cytometry. Curr Opin Hematol 13: 490-495.

- Kecskes Z (2003) Large fetomaternal hemorrhage: clinical presentation and outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 13:128-132.

- Zuppa AA, Scorrano A, Cota F, D’Andrea V, Francciolla A, et al. (2008) Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage and late-onset neutropenia: description of two cases. Turk J Pediatr 50: 400-404.

- Solomonia N, Playforth K, Reynolds EW (2012) Fetal-Maternal Hemorrhage: A Case and Literature Review. AJP Rep 2: 7-14.

- Dziegiel MH, Nielsen LK, Berkowicz A (2006) Detecting fetomaternal hemorrhage by flow cytometry. Curr Opin Hematol 13: 490-495.

- Kecskes Z (2003) Large fetomaternal hemorrhage: clinical presentation and outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 13:128-132.

- Zuppa AA, Scorrano A, Cota F, D’Andrea V, Francciolla A, et al. (2008) Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage and late-onset neutropenia: description of two cases. Turk J Pediatr 50: 400-404.

- Solomonia N, Playforth K, Reynolds EW (2012) Fetal-Maternal Hemorrhage: A Case and Literature Review. AJP Rep 2: 7-14.

- Dziegiel MH, Nielsen LK, Berkowicz A (2006) Detecting fetomaternal hemorrhage by flow cytometry. Curr Opin Hematol 13: 490-495.

- Kecskes Z (2003) Large fetomaternal hemorrhage: clinical presentation and outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 13:128-132.

Citation: Rudrakshi C, Prabhuji MLV, Parween S, Jyothsna S (2017) Relationship between Antioxidants and the Development of the Periodontal Disease. J Cytol Tissue Biol 4: 016.

Copyright: © 2017 Rudrakshi C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.