Relaxed in My Bones: Mother and Child Perspectives on Yoga a Group for Children with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Sarah SmidlDepartment Of Occupational Therapy, Radford University, Radford, Virginia, United States

Tel:+1 5408312690,

Email:ssmidl@RADFORD.EDU

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

There are numerous symptoms associated with ASD that directly impact an individual’s independence and participation in meaningful activities. Those with ASD typically demonstrate deficits in social interaction and communication that decrease their social-emotional reciprocity, understanding and use of non-verbal communication, and their ability to develop friendships. Individuals with ASD also demonstrate restricted interests, hyper or hypo reactivity to sensory stimuli and stereotyped patterns of behavior that may prevent them from trying new things or adapting to changes in routines [4]. In addition to these diagnostic criteria for ASD, many individuals also demonstrate other symptoms such as motor delays and clumsiness, behavioral disturbances and social isolation [5,6]. Additionally, children with ASD have co-occurring diagnoses more frequently than others, with up to 78% being diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), up to 40% with anxiety disorders and up to 20% with depression [7-9].

Numerous therapies are being utilized to address deficits in children with ASD, however, because ASD is a lifelong “spectrum” disorder, the presence and severity of symptoms vary greatly amongst individuals and over time, so there is no effective approach to helping everyone [10,11]. The knowledge that no universal treatment for ASD exists, suggests that the 5,000 year-old philosophy of Yoga could be a potential intervention for those with ASD, specifically considering its holistic and individualized approach. Contrary to many other therapies and Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM), Yoga is meant to be a lifelong practice rather than one that ceases when symptoms of a condition are temporarily alleviated [12]. This purpose of Yoga as an enduring practice aligns naturally with the fact that ASD is a disorder that needs lifelong strategies for improvement or management.

Only a handful of studies have been reported that specifically investigate Yoga as a complementary treatment that may improve the quality of life and functioning for individuals with ASD, and most have small sample sizes, no control groups and limited fidelity measures [13]. However, one study has recently reported high implementation fidelity of a mindfulness-based yoga program for children with ASD and their families [14]. There is preliminary evidence that Yoga can bring qualitative improvements in balance, coordination, self-esteem, self-calming, sensory processing and language skills in children with ASD and related disorders, as well as decreases in behavioral and cognitive symptoms and maladaptive behaviors such as irritability, lethargy, social withdrawal, hyperactivity and noncompliance [15-17]. Yoga has also been shown to improve eye-to-eye gaze, sitting tolerance, and imitation skills for children with Autism engaged in a Yoga program in combination with Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) over a two-year period [18]. In two pretest-post-test designs, increases were found in independence, attention, transition behavior and self-regulation of children with disabilities including ASD and preliminary evidence was found that Yoga can reduce symptoms of ASD based on scores on a child’s scores on the Childhood Autism Rating Scale following Yoga [19,20]. Most recently, an increase in parasympathetic nervous system dominance and decreased heart rate variability in children with Autism was found following a three-month Yoga intervention, which suggests its potential benefit for helping with emotional regulation or anxiety challenges [21].

Despite the few studies that have been conducted on the benefits of Yoga specifically for ASD, there is a growing body of research that supports the use of Yoga to help alleviate a variety of symptoms that are commonly seen in ASD, suggesting Yoga’s potential benefit with this population. A systematic review of 24 studies that investigated the therapeutic effects of Yoga for children without disabilities, support its use to improve behavior, memory, focus, socialization and emotional and physical functioning and none report adverse effects [22]. A systematic review of sixteen studies on Yoga interventions for anxiety reduction in children and adolescents shows that anxiety was reduced in almost all studies, despite some study limitations and varying outcome measures [23]. Other studies suggest that Yoga can be used to improve attention, concentration and emotional control in children with ADHD and improve confidence and communication with peers in children with emotional and behavioral difficulties [24-26].

Overall, there is strong evidence that supports the use of Yoga for numerous physical, emotional and psychological factors in children. However, there is a paucity of research on the potential use of Yoga for children with ASD, and no research that describes the experiences of children with ASD or their caregivers. Because children with ASD have difficulty with social communication and emotional expression, understanding perceptions of their experiences in a Yoga group can be crucial to understanding the potential benefits of a Yoga program for those with this disorder, as well as how to create a Yoga group that will take their specific needs into consideration. Understanding their caregivers’ perceptions can help to discover why Yoga may or may not be used with this population.

METHODS

Participants

Yoga group

The Yoga group was developed by the female researcher, who is a two hundred hour trained Yoga teacher and pediatric occupational therapist with more than twenty years of experience working with children with ASD. The group content and structure was developed based on the researcher’s knowledge of Yoga and the primary deficits of ASD, including the need for routine, decreased social communication, and motor and sensory challenges. Guidance was sought from resources that specifically address the use of Yoga for children with ASD [28,29]. Each Yoga group included introductions with a song, breathing exercises (pranayama), individual and group postures (asana) and savasana (relaxation). Most asanas remained the same each week to support routine and familiarity, and a few were added each week to build skills and add variety.

In order to facilitate social skills and interactions, the group was structured so that children engaged in partner poses and games that required eye contact and communication, and children were encouraged to take the lead and demonstrate different asanas. For example, when engaging in tree circle, the children were required to holds hands around the circle for added balance while observing each other to communicate about which leg (branch) to stand on, while the nature of being in a circle naturally required eye contact amongst members. Since children with ASD are usually visual learners, a visual schedule board was used to outline the components of each group session so the children could follow a routine, and a board was utilized so they could enter the room and hang up their name tag as a transition into group (Table 1).

|

Name introduction song: (5 minutes) |

|

Breathing exercise with Hoberman sphere (10 minutes)

|

|

Standing asanas (10 minutes)

|

|

Crossing the creek game (10 minutes)

|

|

Sitting (10 minutes)

|

|

Supine (5 minutes)

|

|

Savasana (5 minutes)

|

|

Clean up and goodbye (5 minutes) |

Data collection procedures

|

Mother |

Child |

|

Pre-Yoga Group |

Pre-Yoga Group |

|

Can you describe what you already know or what you think about Yoga, and any experiences you have had with it? |

What is Yoga? What have you heard or seen about Yoga? What do you hope Yoga can teach you? |

|

How does Autism impact your child (education, attention, social/sensory/self-help skills)? |

What things are you really good at? What do you like to do for fun? Can you tell me about your friends? |

|

What are the ways that you hope Yoga could benefit your child? |

What things are really hard for you (school, making friends, following directions, etc.)? |

|

Post Yoga Group |

Post Yoga Group |

|

How has your view of Yoga and the potential benefits of Yoga for your child changed or stayed the same? |

What did you learn and like most about the Yoga group (poses, activities, people, etc.)? |

|

Can you talk about any discussions you had with your child about Yoga during the group? |

Can you tell me about the other kids in the group and how you got along with them? |

|

Can you describe any differences you noticed in your child after he or she came to Yoga? |

Can you describe how Yoga made you feel? (body, brain, energy, etc)? |

|

Describe your overall experiences being part of this group. |

Describe your overall experiences being part of this group. |

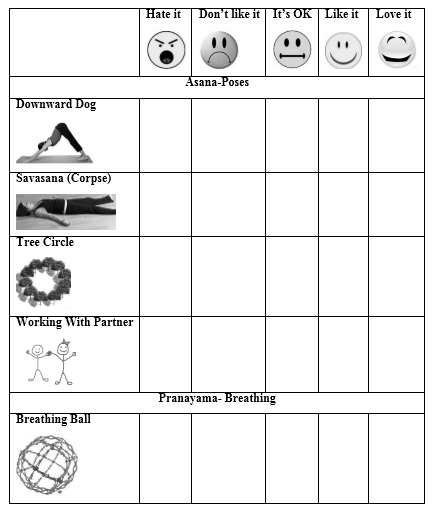

All interviews took place in a private location chosen by the mothers. Interview questions were semi-structured with key questions that were flexible throughout the interview. Each parent interview lasted between thirty and sixty minutes, and each child interview lasted between ten and twenty five minutes. Mothers were interviewed without their child present, and children were given the option of whether they wanted their mothers present. All interviews were tape recorded and interviewees were given pseudonyms. All pre-group interviews were conducted by the researcher and graduate student assistants working with the children, and all post-group interviews were conducted by the graduate student assistants, with interview follow-up and clarification conducted by the researcher. Though different graduate student interviewers were used, the purpose was to provide interview experience for the graduate students, and the researcher’s presence at the first interview ensured thoroughness of interviewing and the ability to provide feedback to students prior to the second interviews. Post Yoga group, a five-point Likert scale with smiley face ratings and a picture of the posture or activity was used to gather information about which postures and parts of Yoga the children most enjoyed. Picture scales were used to address the strong visual skills of children with ASD, as well as the knowledge that children would have difficulty remembering the postures only by name (Table 3).

Data analysis

All Yoga group interviews were transcribed by hand by the graduate student assistants who conducted them, 10 mothers and 12 child interviews total and analyzed by the researcher. Interviews of the mother who had two children in the study were conducted in a group with two graduate students and the researcher. Each interview for this mother was counted as 1 initial and 1 final interview instead of 2 initial and 2 final interviews since their mother spoke of their overall challenges and what she hoped they would gain from Yoga as a whole, instead of differentiating between them, and the researcher did not want to place double emphasis on a single viewpoint in the analysis”.

Each tape recorded interview was listened to once in isolation, and then listened to and read along with the typed transcription by the researcher two times. The researcher sought the feedback of the graduate students following the interviews including their overall perceptions and thoughts, and asking about things that shocked, excited, surprised, or confused them. Next, In Vivo coding was used in order to highlight major ideas of the data, including similarities and differences based on the interview key questions, as well as the frequency of words or phrases [31]. Then, the key ideas were separated into categories with similar data, and the main ideas of the mother and child interviews were categorized and reread together until themes emerged from the data. Responses that children provided on the 5-pointLikert scale about favorite asanas and activities were tallied and averaged to determine which postures were the favorite of the group, in order to give insight for future group planning.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Hesitancy

Despite not knowing much about Yoga or its potential benefits, when asked what they hoped their children would gain from the Yoga group, Ryan’s mother stated, “Helping him deal with his anxiety,” and Johanna’s mother stated, “Helping her make friends and be with other people who understand her. She has a lot of trouble fitting in at school”. Other ideas were, “I don’t really know, but I hear Yoga helps a lot of people deal with stress”, and “I am willing to try anything that will help him, you know, give him tools that will help him get along better in the world”. One mother also described how her son, Samuel, had limited hobbies and did not like new things other than video games and often did not want to go to school, and stated, “I am not sure what I am hoping, but it seems like it might be something that could be really positive for him and help him find a new hobby”. So, despite some of the internal conflicts or questions about the underlying belief system of Yoga and how it might conflict with personal views, families were still willing to try to see if it could help their children with their challenges at home and in school.

Following the group, all mothers reported knowing much more about Yoga and its possible benefits. Ryan’s mom stated, “I have a more favorable impression and realized that Yoga is more comprehensive than what I thought it was. I mean, it was always equated with the ‘ohhmmm’ you know, the chanting, not the positive benefits and relaxation”. One mother reported, “I have heard about Yoga for a long time, and after the group it seems like something that could help him in the long run. I just had no idea!” In further discussion with mothers, all other than Adeline who was homeschooled, discussed how challenging school demands and after school activities often were for their children, and felt there needed to be more opportunities for them to learn how to ease stress and interact more effectively with others. Three of the five mothers wanted to know about other opportunities in the community for their children to continue to practice Yoga, and saw it as both a potential therapy and hobby for their children.

Discovering the reasons why parents or caregivers might not seek Yoga or other complementary therapies for their children is notable, since researchers, practitioners, therapists, educators and program developers may make assumptions of a person’s knowledge or perception of a particular topic or potential treatment. Important to mention is that this Yoga group took place in rural area, which has a high level of religious participation with potentially more conservative viewpoints about CAM and geographical location may prevent families from seeking Yoga or other potentially useful treatments if they feel it is based on religious principles or other non-traditional viewpoints that may conflict with their own.

This acknowledgment of families’ belief systems is crucial as we attempt to provide numerous options and opportunities to increase the health, well-being, or functional skills of children and adolescents with ASD. Providing education to others about Yoga, its history, and its potential uses could help decrease some of the mystery and false beliefs associated with this practice, and could allow caregivers to seek it out for their children. This can also be an important message to Yoga teachers who might be interested in offering a Yoga class for children, since the complex language of Yoga becomes a Yoga teacher’s way of talking, and it is vital to remember to use understandable and neutral language to others who might not be as familiar with its background or terminology.

Loss of self and self-care

Ian and Johanna’s mother expressed, “Your whole life becomes about helping them get along in the world. You worry about who they will be as adults. Will they have real friends? Will they be able to work and have a successful life? What will happen when I am gone?” Following the group, three mothers described how they became interested in the possibility of doing Yoga for themselves after their children started the group. They noticed how the group positively impacted their children, and wondered if it could help them as well. Johanna’s mom stated, “I started to realize how I don’t only need to help her improve how she handles things, but, you know, I also have to improve how I handle my own frustrations. Some days parenting a child with autism is exhausting”. Three other mothers also expressed a loss of self and previously enjoyed activities, a constant heightened state of stress, and having to put their own needs on hold so they could focus on getting their children get to speech therapy or other appointments, fight daily battles because of their child’s rigidity, or plead for them to get their homework done. The natural emergence of this theme is notable for others thinking about creating a Yoga group, and for those working with families with children with ASD overall, since parents who have a child with a disability report more stress and depression than those parenting children without disabilities [32]. ASD impacts the well-being, health and participation of family unit throughout all environments, and working with the whole family and recognizing their needs is crucial for the family unit’s success [33]. For future Yoga groups, having a group for children and parents together could be beneficial to allow the parents to connect to their children and provide the knowledge necessary to carry out a Yoga program more consistently at home. Or, it could be beneficial for Yoga teachers to specifically target parents of children with disabilities to help provide them with some of the tools they require to alleviate their own challenges.

Positive changes

Adeline’s mother described the difference in her involvement in homeschooling, which she believed to be a result of participation in the Yoga group. “We had the greatest two homeschooling weeks in a row. Every day she was on task and we got so much done and she was in a good mood, happy, and wasn’t very argumentative. Monday was a good day and then Tuesday was a good day. Whoa, two days, this is new and then by Wednesday it was like, look this is a fluke; we’ve never had good days three days in a row. And then fourth day, fifth day. I was just awe struck every day”. Ryan’s mother and reported that after getting home from the Yoga each week, he sat right down to do his homework without complaining, and others reported their children had increased focus after the Yoga group and until bed, especially after the first week once the routine had been established.

Ethan’s mother initially described her son as a child who was often worried about what was going to happen next and whether things he did would be right. When she was questioned about if anything had changed for Ethan during the Yoga group, she stated, “That’s what I was thinking, the anxiety and you know, stress of the day, this brought peace, like a peaceful setting and maybe helped him regroup to head back to homework or something that’s not so peaceful. This is a short study, but if it was given significant time I wonder how much difference we would have seen. I don’t know, it just makes me wonder”. Ethan corroborated this idea when he stated, “I feel excited when I come. It is fun and I can be me and I don’t feel like I am going to do anything wrong since you only have to do what you can do, and not what everyone else can do”.

Ian’s mother felt that the Yoga group was carrying over into his daily life. She contemplated, “I think it’s been beneficial. I see Ian trying to practice his breathing, and if he gets upset he does heavy, deep breaths and calms himself down while he repeats the words inhale and exhale”. She discussed how during the last four weeks of the group, he had been more communicative at the end of the school days, especially when they were on their way to Yoga. She also commented that each week, his sister Johanna’s speech therapist reported she was much more focused and on topic when she came to speech therapy after the Yoga group. She also noted that after the first week of Yoga when one of the siblings became upset, the other would tell them to “take a deep breath” or “chill out like a corpse”.

All mothers reported that they felt Yoga was a success, and that their children felt positive about the group and liked coming each week, and that they would enjoy continuing if there was the opportunity to attend another class in the community or at school. All mothers reported their children asked about Yoga when it was over and five of the children asked if they could go again. These positive observations by mothers and children suggest that a long-term practice could magnify the differences seen in this short, 6-week period, and it could be a helpful intervention to continue at both home and in school. Overall, all mothers believed that the collective experience of a supportive Yoga group in a safe and non-judgmental environment over the 6-week period positively impacted their children. The perception of all five mothers was that the children were learning and internalizing Yoga and beginning to use the breathing strategies and postures throughout their day.

Three major themes were also discovered from the children’s interviews.

Instant friends

When the children were asked to rate how they enjoyed working with a partner on the 5-point Likert scale, the average for this component was a 4.7/5. The partner poses became the most requested by the group members. Ryan stated, “I have fun with everyone and got to do Yoga with people I wouldn’t normally talk to. It was easy because we were all doing something new together. The partner poses were really fun”. Reports that the children enjoyed working with others was significant considering the inherent difficulties children with ASD have engaging in social situations, including sharing interests, social reciprocity, and making eye contact and this finding suggests that Yoga could be useful as a tool to utilize these challenging social skills [4]. Samuel discussed, “I don’t talk to a lot of people at school because I am kind of a loner, but I talked to people here ‘because we were here for the same reason”. Ian even went so far as to state, “I even like my sister when I come!” and Ryan laughed and said, “It is like instant noodles, but with friends”. When asked to describe this further, he said, “Like, you had to put us all in the same room and like, just add the Yoga and we all became friends”.

Leader and helper

Ethan thoughtfully stated, “I feel like at school, the teacher asks other kids to help me, and here I got to help instead.” Samuel commented that he felt “it was cool to be able to teach poses to the other kids and get help from the teachers if I needed it”. Knowing the inherent difficulties with social skills of children with ASD, the group structure was purposefully planned by the researcher in order to increase the peer interaction of the group, and its structure naturally encouraged these interactions to take place. On a more global level, this feedback from children suggests the importance that those who care for and teach children with ASD need to be mindful of the impact of self-esteem needs in children with ASD and providing them with leadership and helper opportunities may help build this important skill in a safe and non-judgmental environment. It is hypothesized that the implementation of a Yoga group at school or in the community could assist children with ASD in further developing these challenging social skills and that including partner or group poses may be a crucial piece (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Partner Asana.

Figure 1: Partner Asana.Relaxed in my bones

Important is that three of the children in this study were also co-diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), one was being tested for ADHD and the others reported their children had attention-related difficulties and a decreased ability to sit still for a period of time comparable to their peers. During the interview Samuel’s mom said, “He can just never sit still for one minute, not during homework or school or dinner, really, even when he is playing video games he is moving around”. Mothers reported that attention to task was a concern throughout their school days and homework time, and wanted their children to develop strategies that would help them focus better.

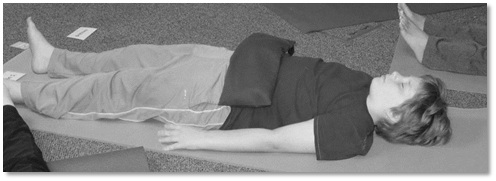

The researcher had to address preconceived biases regarding savasana, as based on the interviews with the mothers, she believed that it would be difficult for the children, and they would wiggle, look around, or talk. However, from the first session, 5 of the children remained completely still on their mats for five minutes with the use of a three-pound sand bag placed across their thighs, abdomen and/or upper shoulders and five requested the use of a lavender-scented eye pillow. Johanna remained on her mat, though wiggled and fidgeted with the sand bag and eye pillow for at least half of savasana each class. The observation that savasana was possible and highly enjoyed and requested by this group, gives support that relaxation techniques and a mindfulness or meditation practice could be a useful strategy for those with ASD to handle attention or anxiety-related issues (Figure 2 & Table 4).

Figure 2: Savasana.

Figure 2: Savasana.|

1 |

Cross the Creek (Group game) |

5.0 |

|

25 |

Lizard Pose |

3.8 |

|

2 |

Rock and Roll |

5.0 |

26 |

Mountain Pose (With scarves) |

3.8 |

|

|

3 |

All of Yoga |

4.8 |

27 |

Camel Pose |

3.7 |

|

|

4 |

Corpse Pose |

4.8 |

28 |

Cow Pose |

3.7 |

|

|

5 |

Sand Bags |

4.8 |

29 |

Eagle Pose |

3.7 |

|

|

6 |

Working with Partner |

4.7 |

30 |

Lightning Pose |

3.7 |

|

|

7 |

Eye Pillows |

4.5 |

31 |

Shoulder Rolls |

3.7 |

|

|

8 |

Puppy Pose (With partner) |

4.5 |

32 |

Triangle Pose |

3.7 |

|

|

9 |

Breathing Ball (Group) |

4.3 |

33 |

Warrior 1 |

3.7 |

|

|

10 |

Down Dog |

4.3 |

34 |

Boat Pose |

3.5 |

|

|

11 |

Lead a Pose |

4.3 |

35 |

Eye Exercises |

3.5 |

|

|

12 |

Using Yoga Blocks |

4.3 |

36 |

Supine Twist |

3.5 |

|

|

13 |

Butterfly Pose (With partner) |

4.2 |

37 |

Lion Face |

3.3 |

|

|

14 |

Help a Classmate |

4.2 |

38 |

Seated Side Bends |

3.3 |

|

|

15 |

Cobra Pose (With partner) |

4.2 |

39 |

Sphinx Pose |

3.3 |

|

|

16 |

Arm Swings |

4.0 |

40 |

Warrior 2 |

3.3 |

|

|

17 |

Dimmed Lights |

4.0 |

41 |

Chair Pose |

3.2 |

|

|

18 |

Plank Pose |

4.0 |

42 |

Create a Pose |

3.2 |

|

|

19 |

Staff Pose (With partner) |

4.0 |

43 |

Freeze |

3.2 |

|

|

20 |

Star Pose |

4.0 |

44 |

Hand and Leg |

3.2 |

|

|

21 |

Tree Circle (Group) |

4.0 |

45 |

Squat |

3.2 |

|

|

22 |

Tree Pose |

4.0 |

46 |

Name Songs |

2.8 |

|

|

23 |

Child’s Pose |

3.8 |

47 |

Bow Pose |

2.7 |

|

|

24 |

Cat Pose |

3.8 |

48 |

Forward Bend |

2.7 |

Study limitations

It is felt that a group longer than 6 weeks would have been useful to determine its longer term impact, especially considering Yoga is a lifelong practice that takes time and experience to develop. The fact that this study was part of a pediatric practicum course, limited its potential length, and many mothers reported they wished it could continue for a longer period of time because they were starting to see changes in their children. Additionally, four of the five mothers stated that they would have liked to occasionally watch or participate with their children during the group in order to get a better idea of what they were doing and how to carry it over at home. A bigger space would have made this possible, and would have allowed increased interaction between mothers, children, and the group facilitators. To help with carryover of the Yoga group, and to address this limitation, each family was given a detailed, individualized Yoga home program for them and their child after the Yoga group ended.

In addition, though receptive and expressive language skills and an ability to participate in interviews was one of the inclusion criteria, the graduate student interviewers and researcher found the two youngest children difficult to interview. They had trouble staying on topic and elaborating on the questions asked, and this limited the full understanding of the experiences of these children.

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019) Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

- Leigh JP, Du J (2015) Brief report: Forecasting the economic burden of autism in 2015 and 2025 in the United States. J Autism Dev Disord 45: 4135-4139.

- Rogge N, Janssen J (2019) The economic costs of autism spectrum disorder: A literature review. J Autism Dev Disord 49: 2873-2900.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5). American Psychiatric Association, Washington, Columbia, USA.

- Bo J, Lee C, Colbert A, Shen B (2016) Do children with autism spectrum disorders have motor learning difficulties? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 23: 50-62.

- Tani M, Kanai C, Ota H, Yamada T, Watanabe H, et al. (2011). Mental and behavioral symptoms of person's with Asperger's syndrome: Relationships with social isolation and handicaps. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6: 907-912.

- Stevens T, Peng L, Barnard-Brak L (2016) The comorbidity of ADHD in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 31: 11-18.

- van Steesel FJA, Heeman EJ (2017) Anxiety Levels in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. J Child Fam Stud 26: 1753-1767.

- Greenlee JL, Mosley AS, Shui AM, Veenstra-VanderWheele J, Gotham KO (2016) Medical and behavioral correlates of depression history in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 137(S2): 105-114.

- Ehleringer J (2010) Yoga therapy in practice: Yoga for Children on the Autism Spectrum. International Journal of Yoga Therapy 20: 131-139.

- Ghosh S, Koch M, Suresh-Kumar V, Rao AN (2009) Do alternative therapies have a role in autism? Online Journal of Health andAllied Sciences 8: 1-6.

- Iyengar BKS (1965) Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, Australia.

- Semple RJ (2019) Review: Yoga and mindfulness for youth with autism spectrum disorder: Review of the current evidence. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 24: 12-18.

- Garcia JM, Baker K, Diaz MR, Tucker JE, Kelchner VP, et al. (2019) Implementation fidelity of a mindfulness-based yoga program for children with autism spectrum disorder and their families: A pilot study. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders 3: 54-62.

- Kenny M (2002) Integrated Movement Therapy™: Yoga-Based Therapy as a Viable and Effective Intervention for Autism Spectrum and Related Disorders. International Journal of Yoga Therapy 12: 71-79.

- Rosenblatt LE, Sasikanth G, Torres JA, Yarmush RS, Rao S, et al. (2011) Relaxation response-based yoga improves functioning in young children with autism: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 17: 1029-1035.

- Koenig KP, Buckley-Reen A, Garg S (2012) Efficacy of the get ready to learn yoga program among children with autism spectrum disorders: A pretest-posttest control group design. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 66: 538-546.

- Radhakrishna S, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR (2010) Integrated approach to yoga therapy and autism spectrum disorders. J Ayurveda Integr Med 1: 120-123.

- Garg S, Buckley-Reen A, Alexander L, Chintakrindi R, Tan L, et al. (2013) The Effectiveness of a Manualized Yoga Intervention on Classroom Behaviors in Elementary School Children with Disabilities: A Pilot Study. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention 6: 158-164.

- Deorari M, Bhardwaj I (2014) Effect of yogic intervention on autism spectrum disorder. Yoga Mimamsa 46: 81-84.

- Vidyashree HM, Maheshkumar L, Susdareswaran L, Sakthivel G, Partheeban PK, et al. (2018) Effect of yoga intervention on short-term heart rate variability in children with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Yoga 12: 73-77.

- Galantino ML, Galbavy R, Quinn L (2008) Therapeutic effects of yoga for children: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatric Physical Therapy 20: 66-80.

- Weaver LL, Darragh AR (2015) Systematic review of yoga interventions for anxiety reduction among children and adolescents. Am J Occup Ther 69: 1-9.

- Jensen PS, Kenny DT (2004). The effects of yoga on the attention and behavior of boys with Attention-Deficit/ hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). J Atten Disord 7: 205-216.

- Peck HL, Kehle TJ, Bray MA, Theodore LA (2005) Research to practice: Yoga as an intervention for children with attention problems. SchoolPsychology Review 34: 415-424.

- Powell L, Gilchrist M, Stapley J (2008) A journey of self?discovery: an intervention involving massage, yoga and relaxation for children with emotional and behavioural difficulties attending primary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education 23: 403-412.

- American Occupational Therapy Association (2017) Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd edn). American Journal of Occupational Therapy 68: 1-48.

- Betts DE, Betts SW (2006) Yoga for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Step-By-Step Guide for Parents and Caregivers. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK.

- Goldberg L (2013) Yoga Therapy for Children with Autism and Special Needs. W. Norton & Company. New York, USA.

- van Manen M (2014) Phenomenology of Practice: Meaning Giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing. Left Cost Press, Walnut Creek, California, USA.

- Saldana J (2016) The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (3rd edn). SAGE, Thousand Oaks, California, USA.

- Van Steijn DJ, Oerlemans AM, Van Aken MA, Buitelaar JK, Rommelse NN (2014) The reciprocal relationship of ASD, ADHD, depressive symptoms and stress in parents of children with ASD and/or ADHD. J Autism Dev Disord 44: 1064-1076.

- American Occupational Therapy Association (2010) The Scope of Occupational Therapy Services for Individuals With an Autism Spectrum Disorder Across the Life Course. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(Supp l): 125-136.

Citation: Smidl S (2019) Relaxed in My Bones: Mother and Child Perspectives on Yoga a Group for Children with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. J Altern Complement Integr Med 5: 77.

Copyright: © 2019 Sarah Smidl, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.