Seroprevalence and Co-infection of Hepatitis A and Hepatitis E Viruses in children - A hospital-based study in Bangladesh

*Corresponding Author(s):

Bodhrun NaherDepartment Of Pediatric Gastroenterology And Nutrition, Bangabandhu, Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh

Tel:+880 01712270844,

Email:bodhrunnaher@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Viral hepatitis is a serious health problem globally and in endemic countries like Bangladesh. Viral hepatitis may present as mono-infection or co-infection caused by Hepatitis A Virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, and Hepatitis E Virus (HEV). Enterically transmitted viral agents like Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) and Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) are common causes of viral hepatitis in developing countries. Double infections by both agents, as their routes of entry are similar, are common. Co-infection with two or more viruses may lead to serious complications and increased mortality.

Objective: This study was carried out to learn about the seroprevalence of HAV & HEV (and double infections if any) infections in Acute Viral Hepatitis (AVH) cases attending our hospital.

Materials and Methods: This is a retrospective cross-sectional study of a 2 years duration carried out in the Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition department of BSMMU, Dhaka. Total 400 cases, presenting with Acute Viral Hepatitis were included in the study. Cases with suggestive history were tested for IgM anti-HAV and IgM anti-HEV respectively.

Results: Out of 400 samples, 100 samples were positive for HAV and/or HEV infection with an overall prevalence of 24.7%. HAV & HEV seroprevalence in AVH cases were found to be 13.75% (55/400) and 5.75% (23/400), respectively. Dual infection of HAV and HEV was found in 5.25% (21/400) of study subjects. Both years, most of the positive cases are seen in the months of August and September.

Keywords

Acute viral hepatitis; Enterically transmitted hepatitis; HAV; HEV co-infection

Introduction

Viral hepatitis is a major public health problem in Bangladesh and worldwide. Cases have been reported throughout the country [1]. Primarily, viral hepatitis is caused by Hepatitis A Virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus, hepatitis D virus, Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) and dengue virus [2,3].

Hepatitis A is caused by HAV that affects liver [4] and found worldwide. It is a non-enveloped 27-nm RNA virus in the genus Hepatovirus of the family Picornaviridae [5]. HAV resulted in approximately 1.4 million cases worldwide annually and 27,731 deaths in 2010, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [4]. Since the introduction of the hepatitis A vaccine and the start of mass vaccination in several countries in the 1980s, hepatitis A incidence has declined substantially, not only among vaccinated children but in the population as a whole [2-3]. HAV and HEV infections are endemic in many low-income settings. In Asia, many countries have been reported as low, moderate, or high endemic regions for HAV infection [4,5]. Regions of high endemicity include Bangladesh, as well as India, China, Nepal, Pakistan, Myanmar and the Philippines [6].

On the other side, hepatitis E is caused by the HEV that is a non-enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid virus in the genus Hepevirus of the family Hepeviridae [5]. Globally, there are around 20 million hepatitis E infections/ years are being reported, over which 3 million cases are symptomatic [6]. Around 56, 600 deaths/year are related to hepatitis E [6]. The anti-HEV IgM antibody appears soon after an acute infection and falls to a very low level within 6 months of infection [5]. HEV is reported to be the agent of 20-60% of cases of sporadic acute hepatitis with fulminant liver failure [5]. HEV infection is observed to be higher amongst the pregnant women than seen amongst non-pregnant ladies with AVH [5].

Mode of transmission of HAV and HEV is via feco-oral route, mainly through contaminated water. Outbreaks and sporadic cases of hepatitis A and E occur globally but are closely associated with unsafe water, inadequate sanitation and poor hygiene and health services in resource-limited countries. Hepatitis A and E are usually self-limiting diseases but can develop into fulminant hepatitis (acute liver failure) [2,4,6].

HAV mainly affects infants and young children in developing countries, whereas HEV primarily affects older children and young adults [7-9]. Clinically, hepatitis A and E infections may present as asymptomatic infection or mild hepatitis or subacute liver failure [10,11].

In patient with preexisting chronic liver disease, both HAV and HEV infection can worsen the condition. The clinical course of HEV is more problematic than HAV infection, primarily in pregnant females, contract disease in the second and third trimester. Therefore, HAV-HEV co-infection can lead to serious complications and increased mortality because of acute liver failure in patients in children as well as adults [12,13].

Although clinical diagnosis of co-existence of HAV and HEV viruses as a cause of viral hepatitis is difficult and cannot be differentiated with monoinfection, laboratory diagnosis either by serology and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) can be a useful tool in the diagnosis of simultaneous presence of both the viruses [11,14].

In our study, we have studied the seroprevalence and co-infection of HAV and HEV infections in various age groups of children. Study on seasonal variation of HAV/HEV infections was also included in the study.

Materials And Methods

This was a retrospective study spanning a period of 2 years (April 2019 to March 2021) which included a total of 400 patients. Patients of 0-15 years of age attending BSMMU (indoor and outdoor) with a clinical diagnosis of acute viral hepatitis were included in this study. About 3-5 ml serum was collected and were tested for HAV and HEV Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies. HAV IgM and HEV IgM antibodies were detected by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kits (DRG International, Inc., USA), according to manufacturer instructions. Data were collected in a Microsoft excel sheet and analyzed by using SPSS version 25. The Chi-square (χ2) and Fisher’s exact test were put to use to check statistically significant associations between various demographic factors with HAV and HEV results.

Results

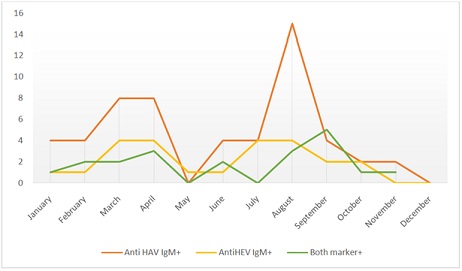

Out of a total of 400 samples, 100 samples yielded reactive ELISA, 79 being single agent (HAV or HEV) and 21 mixed (Both HAV and HEV) which were shown in tables 1 & 2. Among 100 positive cases of either hepatitis A or hepatitis E or both, 22 cases were < 5 years, 53 cases were 6-10 years and 25 were in 11-15 years of age (Table 1). The overall prevalence of HAV and HEV infection was found 24.7%. The prevalence of HAV infection was found 13.75%, HEV infection 5.7% and HAV/HEV co-infection was 5.2% which was depicted in table 3. Figure 1 showed the seasonal variation of HAV/HEV positive cases.

|

Age group |

Total cases studied |

Only HAV positive MaleFemale |

Only HEV positive MaleFemale |

||

|

<5 |

22 |

6 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

|

6-10 |

53 |

18 |

12 |

8 |

5 |

|

11-15 |

25 |

9 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

Table 1: Age-wise distribution of HAV and HEV positive cases.

HAV: Hepatitis A Virus, HEV: Hepatitis E Virus.

|

Age group |

Total cases studied |

Both HAV positive & HEV positive Male Female |

|

|

<5 |

22 |

3 |

2 |

|

6-10 |

53 |

5 |

5 |

|

11-15 |

25 |

4 |

2 |

Table 2: Age-wise distribution of HAV and HEV co-infected cases.

HAV: Hepatitis A virus, HEV: Hepatitis E virus.

|

|

Number of cases |

Prevalence (%) |

|

HAV positive |

55 |

13.75 |

|

HEV positive |

24 |

5.7 |

|

HAV & HEV both positive |

21 |

5.2 |

Table 3: Prevalence of HAV, HEV mono infection and Co-infection by HAV & HEV.

Figure 1: Seasonal variation of HAV/HEV positive cases.

Figure 1: Seasonal variation of HAV/HEV positive cases.

Discussion

Globally, HAV is found common cause of viral hepatitis [15,16]. In the present study, 24.7% (HAV 13.75%, HEV 5.75% and both 5.2%) of the AVH patients had a reactive viral marker. This reactive rate is lower to Al-Naimy et al.’s 43% [11]. But Joon et al. from India reported a viral (HAV, HEV) infection rate of 29.9% with HAV & HEV being 19.31% and 10.54%, respectively. The co-infection rate in this study was 11.5% which is similar to our study [12]. In a large nationwide study carried out in Bangladesh 19% HAV and 10% HEV cases were detected with a median age of 12 and 25 years respectively. HAV was found more in females while HEV attacked males dominantly. A clear seasonal variation for both infections with a higher number of cases in July to September period was observed [14]. Samadar et al. observed a higher seroprevalence of HEV (9.63%) compared to HAV (6.96%) with a coinfection rate of 2.07% in a population of acute hepatitis [15]. A seasonal trend was observed with a higher incidence in May to September (summer and rainy season) [15]. In a Cuban study by Rodríguez Lay Lde et al. 36.4% of subjects were positive for HAV (IgM), 21.2% for HEV (IgM) while a whopping 42.4% had IgM antibody to both HAV & HEV [17]. A Japanese study by Takahashi et al. on the other hand found 100% positivity to HAV in the adult population (23-86 years group) while anti HEV was found in 11% only [18].

Age-wise distribution of HAV and HEV IgM positive cases is depicted in table 1. Age-wise distribution of HAV and HEV co-infected cases is illustrated in table 2. Probability of lower HEV infection rates in children may be due to: (1) Anicteric HEV infections, therefore, children can go unnoticed [19]. (2) Subclinical HEV infections in the endemic area make children more immune and adult more vulnerable for HEV infection [13,20].

Co-infection with HAV and HEV was found in 21 cases with the seroprevalence of 5.2% It is similar in various other studies also [21-25] shown in table 4.

|

Study |

HAV and HEV co infection |

|

Das et al. [21] |

5.31% |

|

Sarguna et al. [22] |

5.31% |

|

Jain et al. [23] |

8.61% (23 cases) |

|

Arora et al. [24] |

7.5% (5 cases) |

|

Poddar et al. [25] |

7 per cent (12 cases) |

|

Our study |

5.2% (21 cases) |

Table 4: Comparative evaluation of HAV-HEV co-infection in different studies.

Co-infection with HAV and HEV does not affect the prognosis of the patient much as these cases usually resolve with conservative treatment but in rare cases may lead to acute liver failure or hepatic encephalopathy [12,13,22].

Although it is always a difficult to diagnose HAV/HEV co-infection clinically and by biochemical analysis, serology and PCR may help in timely diagnosis and identification of causative agent and support in prevention and management of acute liver failure in children in Bangladesh.

Seasonal variation of HAV and HEV was also studied as depicted in figure 1. Cases were reported throughout the year as these infections are endemic in Bangladesh, with the peak of maximum number in August that is the rainy season. It is possible that cross contamination of drinking water with sewage could be more common during rainy season [26].

Both HAV and HEV prevalence were detected higher in males than in females which had correlated well with another study. Outdoor and social activities of males may make them more vulnerable for the exposure than females [27].

HAV and HEV infections are enterically transmitted and have similar risk factors, therefore the most effective method to control viral hepatitis is to prevent infection. That can be done by interrupting the route of transmission and focusing on proper sanitary condition, hygiene and public education [2].

Simultaneously vaccines can be used as a preventive strategy. Although HAV vaccine is in the market but not easily accessible and extremely high prevalence of anti-HAV antibody in the general population make it less cost effective for mass immunization in country like Bangladesh, can be used in risk population like during onset of epidemics, chronic liver disease patients, travelers visiting endemic areas, etc. As HAV infection is common in younger children, inclusion of single dose inactivated HAV vaccine in immunization schedule of children can be useful [2,3,11].

No specific treatment is available, complete rest following infection is important for recovery. Infection resolves without any sequel most of the time but in rare case of acute viral hepatitis or fulminant liver failure, liver transplantation is the end treatment [3,13].

References

- Irshad M, Singh S, Ansari MA, Joshi YK (2010) Viral hepatitis in India: A report from Delhi. Glob J Health Sci 2: 96-103.

- Acharya SK, Madan K, Dattagupta S, Panda SK (2006) Viral hepatitis in India. Natl Med J India 19: 203-217.

- Pandit A, Mathew LG, Bavdekar A, Mehta S, Ramakrishnan G, et al. (2015) Hepatotropic viruses as etiological agents of acute liver failure and related-outcomes among children in India: A retrospective hospital-based study. BMC Res Notes 8: 381.

- WHO (2015) Hepatitis A. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, et al. (2001) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e, (5th edn). World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland. Pg no: 1694-1710.

- WHO (2015) Hepatitis E. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Kumar T, Shrivastava A, Kumar A, Laserson KF, Narain JP, et al. (2015) Viral hepatitis surveillance - India, 2011-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64: 758-762.

- Arankalle VA, Chadha MS, Chitambar SD, Walimbe AM, Chobe LP, et al. (2001) Changing epidemiology of hepatitis A and hepatitis E in urban and rural India (1982-98). J Viral Hepat 8: 293-303.

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH (2004) Running like water - The omnipresence of hepatitis E. N Engl J Med 351: 2367-2368.

- Dalton HR, Bendall R, Ijaz S, Banks M (2008) Hepatitis E: An emerging infection in developed countries. Lancet Infect Dis 8: 698-709.

- Al-Naaimi AS, Turky AM, Khaleel HA, Jalil RW, Mekhlef OA, et al. (2012) Predicting acute viral hepatitis serum markers (A and E) in patients with suspected acute viral hepatitis attending primary health care centers in Baghdad: A one year cross-sectional study. Glob J Health Sci 4: 172-183.

- Joon A, Rao P, Shenoy SM, Baliga S (2015) Prevalence of Hepatitis A virus (HAV) and Hepatitis E virus (HEV) in the patients presenting with acute viral hepatitis. Indian J Med Microbiol 33: 102-105.

- Barde PV, Chouksey VK, Shivlata L, Sahare LK, Thakur AK (2019) Viral hepatitis among acute hepatitis patients attending tertiary care hospital in central India. Virusdisease 30: 367-372.

- Khan AI, Salimuzzaman M, Islam MT, Afrad MH, Shirin T, et al. (2020) Nationwide hospital-based seroprevalence of Hepatitis A and Hepatitis E virus in Bangladesh. Ann Glob Health 86: 29.

- Samaddar A, Taklikar S, Kale P, Kumar CA, Baveja S (2019) Infectious hepatitis: A 3-year retrospective study at a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J Med Microbiol 37: 230-234.

- Malhotra B, Deba F, Sharma P, Trivedi K, Tiwari J, et al. (2020) Hepatitis E outbreak in Jaipur due to Genotype IA. Indian J Med Microbiol 38: 46-51.

- Lay RLL, Quintana A, Villalba MC, Lemos G, Corredor MB, et al. (2008) Dual infection with hepatitis A and E viruses in outbreaks and in sporadic clinical cases: Cuba 1998-2003. J Med Virol 80: 798-802.

- Takahashi M, Nishizawa T, Gotanda Y, Tsuda F, Komatsu F, et al. (2004) High prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis A and E viruses and viremia of hepatitis B, C, and D viruses among apparently healthy populations in Mongolia. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 11: 392-398.

- Radhakrishnan S, Raghuraman S, Abraham P, Kurian G, Chandy G, et al. (2000) Prevalence of enterically transmitted hepatitis viruses in patients attending a tertiary--care hospital in South India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 43: 433-436.

- Park JH, Kim BS, Lee CH, Kim SY, Seo JH, et al. (2011) A case of coinfection of Hepatitis A and E virus with hepatic encephalopathy. Korean J Med 80: 101-105.

- Das AK, Ahmed S, Medhi S, Kar P (2014) Changing patterns of aetiology of acute sporadic viral hepatitis in India - Newer insights from North-East India. Int J Curr Res Rev 6: 14-20.

- Sarguna P, Rao A, Ramana KNS (2007) Outbreak of acute viral hepatitis due to hepatitis E virus in Hyderabad. Indian J Med Microbiol 25: 378-382.

- Jain P, Prakash S, Gupta S, Singh KP, Shrivastava S, et al. (2013) Prevalence of hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus and hepatitis E virus as causes of acute viral hepatitis in North India: A hospital based study. Indian J Med Microbiol 31: 261-265.

- Arora D, Jindal N, Shukla RK, Bansal R (2013) Water borne hepatitis a and hepatitis e in Malwa region of Punjab, India. J Clin Diagn Res 7: 2163-2166.

- Poddar U, Thapa BR, Prasad A, Singh K (2002) Changing spectrum of sporadic acute viral hepatitis in Indian children. J Trop Pediatr 48: 210-213.

- Kamal SM, Mahmoud S, Hafez T, El-Fouly R (2010) Viral hepatitis A to E in South mediterranean countries. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2: 2010001.

- Aggarwal R, Krawczynski K (2000) Hepatitis E: An overview and recent advances in clinical and laboratory research. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 15: 9-20.

Citation: Naher B, Islam R, Ghosal S, Nahid KL, Rukunuzzaman (2021) Seroprevalence and Co-infection of Hepatitis A and Hepatitis E Viruses in children - A hospital-based study in Bangladesh. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 8: 080.

Copyright: © 2021 Bodhrun Naher, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.