Slow versus Rapid Advancement of Enteral Feeding in Preterm Infants Less than 34 Weeks: A Randomized Controlled Trial

*Corresponding Author(s):

Liton Chandra SahaDepartment Of Neonatal Medicine, Bangladesh Institute Of Child Health, Dhaka Shishu Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Tel:+880 1711463273,

Email:sahaliton11@gmail.com, sahaliton11@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background

Enteral feeding routines are not well de?ned in preterm neonates. Controversy exists regarding when feedings should be started, whether minimal enteral feedings should be used routinely in small preterm infants and how fast to advance enteral feedings.

Objective

To evaluate the effect of slow vs rapid rates of advancement of enteral feeding volumes on the clinical outcomes in preterm babies less than 34 weeks.

Methodology

A randomized, controlled, single-center trial was conducted in a Neonatal Unit of Dhaka Shishu (Children) Hospital. Infants between 1200 gm and < 2500 gm at birth, gestational age < 34 weeks, and weight appropriate for gestational age were allocated randomly to feedings of expressed human milk and advanced at either 30 mL/kg per day or 20 mL/kg per day. Infant’s remained in the study until discharge.

Results

A total of 300 infants were enrolled, 150 infants in the rapid group and 150 in the slow group. Enteral feeding advancements were well tolerated by the intervention group of stable preterm neonates like that of control group both in birth weight <1500 gm and in birth weight (1500 gm - < 2500 gm) study populations (67.27 % vs. 68.42 % and 68.42 % vs. 64.28 %, p value > 0.05). Infants in the intervention group achieved full volume feedings sooner (9.33 days vs. 14.66 days) and (9.12 days vs. 15.5 days), p value < 0.05. Eighteen infants in the intervention group and fifteen in control group were died due to sepsis which was statistically not significant. There was no incidence of NEC in birth weight (1500 gm - < 2500 gm) study populations in both groups. No statistical differences in the proportion of infants with feed interruption or feed intolerance.

Conclusion

Rapid enteral feeding advancements in preterm babies < 34 weeks reduce the time to reach full enteral feeding and the use of PN administration. Rapid-advancement enteral feed also improved short-term outcomes for these high-risk infants.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

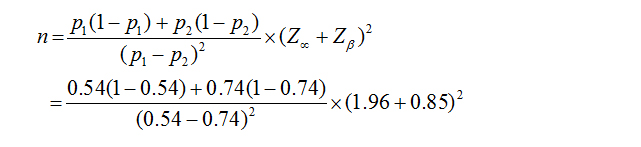

Sample size has been calculated with the formula:

P2 = Outcome in case 74 % (0.74)

Zα = 1.96

Zβ = 0.85 (at 80 % power)]

N = 87 (in each group)

RESULTS

|

Parameters |

Slow Group (n = 150) |

Rapid Group (n = 150) |

p value |

|

Gestational age (Wks) |

31.65 (± 1.85) |

30.75 (± 1.11) |

0.28 |

|

Weight on admission (gm) |

1633.70 (± 322.25) |

1700.58 (± 230.44) |

0.07 |

|

Enrolment age (hours) |

38.56 (± 1.74) |

39.17 (± 1.55) |

0.30 |

|

Sex |

|||

|

92 |

87 |

0.53 |

|

58 |

63 |

|

|

Characteristics |

Slow n = 55 |

Rapid n = 38 |

Total |

p value* |

|

Feeding tolerance |

37 (67.27 %) |

26 (68.42 %) |

63 |

0.82 |

|

Feeding intolerance |

18 (32.73 %) |

12 (31.58 %) |

40 |

1.0 |

|

Abdominal distention |

12 (21.81 %) |

09 (23.68 %) |

21 |

0.65 |

|

Vomiting |

27 (49 %) |

16 (42.10 %) |

43 |

0.87 |

|

Increase gastric residual/Gastric aspirates > 50 % |

12 (21.81 %) |

08 (21.05 %) |

20 |

0.79 |

|

Feeding interruption |

15 (27.27 %) |

10 (26.31 %) |

25 |

1.0 |

|

Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) |

3 (5.45 %) |

2 (5.26 %) |

5 |

0.27 |

|

*χ2 test |

||||

|

Baseline characteristics |

Slow n = 95 |

Rapid n = 112 |

Total |

p value* |

|

Feeding tolerance |

65 (68.42 %) |

72 (64.28 %) |

137 |

0.34 |

|

Feeding intolerance |

30 (31.58 %) |

40 (35.71 %) |

70 |

0.47 |

|

Abdominal distention |

36 (37.89 %) |

44 (39.28 %) |

80 |

0.95 |

|

Vomiting |

30 (31.57 %) |

32 (28.57 %) |

62 |

0.87 |

|

Increase gastric residual/Gastric aspirates > 50 % |

12 (12.63 %) |

14 (12.5 %) |

26 |

0.44 |

|

Feeding interruption |

27 (28.42 %) |

36 (32.14 %) |

63 |

0.85 |

|

Necrotizing Entero Colitis (NEC) |

00 |

00 |

00 |

-- |

|

*χ2 test |

||||

|

|

Slow group (n = 55) |

Rapid group (n = 38) |

p value* |

||

|

|

Mean |

± SD |

Mean |

± SD |

|

|

Duration of IV fluid (days) |

9.33 |

0.30 |

6.66 |

0.50 |

<0.001 |

|

Time taken for full enteral feed (days) |

14.66 |

0.58 |

9.33 |

0.50 |

<0.001 |

|

Duration of Hospital Stay (days) |

17.38 |

0.75 |

13.14 |

2.11 |

0.003 |

|

Days to regain birth weight |

12.72 |

0.76 |

7.86 |

1.06 |

0.001 |

|

*Independent ‘t’ test |

|||||

|

|

Slow group (n = 95) |

Rapid group (n = 112) |

P value* |

||

|

|

Mean |

± SD |

Mean |

± SD |

|

|

Duration of IV fluid (days) |

10.00 |

0.84 |

5.75 |

0.98 |

<0.001 |

|

Time taken for full enteral feed (days) |

14.50 |

1.29 |

9.12 |

0.79 |

<0.001 |

|

Duration of hospital stay (days) |

16.50 |

2.48 |

12.13 |

1.50 |

<0.001 |

|

Days to regain birth weight |

11.88 |

2.21 |

7.93 |

1.48 |

<0.001 |

|

*Independent ‘t’ test |

|||||

|

Weight in admission |

Study group |

Total |

p value* |

|||

|

Slow |

Rapid |

|||||

|

< 1500 gm |

Outcome |

Discharged with Breast feeding |

48 |

34 |

82 |

1 |

|

Died |

7 |

4 |

11 |

|||

|

Total |

55 |

38 |

93 |

|||

|

1500 - < 2200 gm |

Outcome |

Discharged with Breast feeding |

87 |

98 |

185 |

0.68 |

|

Died |

8 |

14 |

20 |

|||

|

Total |

95 |

112 |

207 |

|||

|

Grand Total |

n = 150 |

n = 150 |

300 |

|||

|

*χ2 test |

||||||

DISCUSSION

Both slow and rapid enteral feeding groups were comparable in gestational age, weight on admission, age on admission and sex. There was no significant difference of these demographic characteristics of the study population between the two groups. Enteral feeding advancements were well tolerated by the intervention group of stable preterm neonates like that of control group both in birth weight < 1500 gm and in birth weight (1500 gm - < 2500 gm) study populations (67.27 % vs. 68.42 % and 68.42 % vs. 64.28 %, p value > 0.05). This finding is also consistent with previous studies done by Caple J. et al., and Krishnamurthy S [11,12].

Rapid enteral feeding group needed shorter duration of Intravenous fluid than slow enteral feeding group both in birth weight < 1500 gm and in birth weight (1500 gm - < 2500 gm) study populations (6.66 days vs. 9.33 days and 5.75 days vs. 10.00 days, p value > 0.05). This is consistence with some previous studies done by Caple J. et al., and Krishnamurthy S [11,12].

Infants in the intervention group achieved full volume feedings sooner (9.33 days vs. 14.66 days) and (9.12 days vs. 15.5 days), p value < 0.05. This is also consistence with some previous studies done by Caple J. et al., and Krishnamurthy S [11,12].

Rapid enteral feeding took significantly fewer days to regain weight than slow enteral feeding both in birth weight < 1500 gm and in birth weight (1500 gm - < 2500 gm) study populations (7.86 days vs. 12.72 days and 7.93 days vs. 11.88 days, p value > 0.05). This finding is well supported by Cochrane review conducted by Opiyo N. et al. Oxford University, Oxford, UK, 2009 [13]. In rapid enteral feeding group regained weight is earlier because calorie intake was high in comparison to slow feeding group. As it is not possible for us to provide TPN (Total Parenteral Nutrition) in preterm low birth weight babies because it is expensive and its administration procedure is not well established in our hospital setup.

Rapid enteral feeding took significantly shorter duration of hospital stay than slow enteral feeding. This is consistence with some previous studies done by Krishnamurthy S, 2010 and Karagol BS et al., [12,14]. But there was no significant difference between the two groups in few other studies which were conducted by Caple J et al., and Rayyis and Salhotra A [9,11,15]. In their studies, both the groups were kept in the hospital until they reached to the higher limit of the weight of their respective age group but the long-term clinical importance of these effects are unclear. Feeding was interrupted in both slow and rapid enteral feeding groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. This is also similar with few other related studies done by Caple J. et al., and Krishnamurthy S [11,12].

Frequency of feeding complication e.g. abdominal distention, feeding intolerance and increase gastric residual were more in rapid enteral feeding than slow enteral feeding, but there was no significance difference between these two groups; p value for mentioned variables were > 0.05. It also confirmed with all the mentioned previous studies. In case of vomiting the frequency was more in slow enteral feeding than rapid one, but again this is not statistically significant; p value > 0.05.

Regarding Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC), there was no significant difference for both the groups in this study. Meticulous observation, proper sepsis screening and prophylactic antibiotic was given when necessary. Moreover, only breast milk was provided and no formula milk was added in this study. In all the previous mentioned studies, few incidents of NEC were present and it was similar for both the groups but not statistically significant [9,11-16].

In this study, mortality was almost equal (10.00 % vs. 12.00 %; p value was > 0.05) for both in slow feeding and rapid feeding due to only sepsis which was statistically not significant. In all the previous mentioned studies, little mortality was found due to both NEC and sepsis; these incidents of NEC and sepsis were similar for both the groups but not statistically significant where the study was done by Caple J. et al., and Krishnamurthy et al. [11,12].

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

- Cooke RJ (2003) Nutrient requirements in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 53: 2.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (1985) Nutritional needs of low-birth-weight infants. Pediatrics 75: 976-986.

- Clark RH, Thomas P, Peabody J (2003) Extrauterine growth restriction remains a serious problem in prematurely born neonates. Pediatrics 111: 986-990.

- Fletcher AB (1994) Nutrition. In: Avery GB (eds.). Neonatology (4th edn). Lippincott, Philadelphia, USA. Pg no: 330-356.

- LaGamma, EF, Ostertag, SG, Birenbaum H (1985) Failure of delayed oral feedings to prevent necrotizing enterocolitis. Results of study in very-low-birth-weight neonates. Am J Dis Child 139: 385-389.

- Berseth CL, Nordyke C (1993) Enteral nutrients promote postnatal maturation of intestinal motor activity in preterm infants. Am J Physiol 264: 1046-1051.

- Book LS, Herbst JJ, Jung AL (1976) Comparison of fast- and slow- feeding rate schedules to the development of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr 89: 463-466.

- Rayyis S, Ambalavanan N, Wright L, Carlo WA (1999) Randomized trial of “slow” versus “fast” feed advancements on the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 134: 293-297.

- Anderson DM, Kliegman RM (1991) The relationship of neonatal alimentation practices to the occurrence of endemic necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Perinatol 8: 62-67.

- McKeown RE, Marsh TD, Amarnath U, Garrison CZ, Addy CL, et al. (1992) Role of delayed feeding and of feeding increments in necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr 121: 764-770.

- Caple J, Armentrout D, Huseby V, Halbardier B, Garcia J, et al. (2004) Randomized, Controlled Trial of Slow Versus Rapid Feeding Volume Advancement in Preterm Infants. Pediatrics 114: 1597-1600.

- Krishnamurthy S, Gupta P, Debnath S, Gomber S (2010) Slow versus rapid enteral feeding advancement in preterm newborn infants 1000-1499 g: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Paediatrica 99: 42-46.

- Opiyo N, Ngetich E, English M (2009) Cochrane review on Initiation of enteral feeding in preterm infants - how does evidence inform current strategies.

- Karagol BS, Zencioglu A, Okumus N, Polin RA (2008) Randomized controlled trial of slow vs rapid enteral feeding advancements on the clinical outcomes of preterm infants with birth weight 750-1250 g. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 37: 223-228.

- Salhotra A, Ramji S (2003) Slow versus fast enteral feed advancement in very low birth weight infants: A randomized control trial. Indian Pediatr 41: 435-441.

- Ronnestad A, Abrahamsen TG, Medbo S, Reigstad H, Lossius K, et al. (2005) Late-onset septicemia in a Norwegian national cohort of extremely premature infants receiving very early full human milk feeding. Pediatrics 115: 269-276.

Citation: Saha LC, Yaesmin R, Hoque M, Chowdhury MAKA (2019) Slow versus Rapid Advancement of Enteral Feeding in Preterm Infants Less than 34 Weeks: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 6: 029.

Copyright: © 2019 Liton Chandra Saha, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.