Sonographic Presentation of Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM)

*Corresponding Author(s):

Iqra ManzoorGilani Ultrasound Center, Afro-Asian Institute, Ferozpur Road, Lahore, Pakistan

Tel:+92 03336422555,

Email:iqramanzoor36@gmail.com

Abstract

Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM) is a potentially life-threatening condition. It is a rare vascular problem of the uterus that’s why its true prevalence is unknown. Currently, very fewer cases are reported in the literature. It is an abnormal communication of arteries and veins without intervening capillary network, within the uterine wall. We report a case of a 36-year-old woman who was presented to our ultrasound clinic with menorrhagia. One year back she gave birth to a male child with normal per vaginal delivery. She was too pale and faint (anemic) while suffering from intermittent per vaginal bleeding for 26 days. We performed a transabdominal gynecological ultrasound with full urinary bladder according to the AIUM guidelines, which are routinely observed in this clinic. Informed consent was signed by the patient husband (legal guardian) for publishing her data. We observed prominent vessels in the right-sided uterine wall with the multidirectional low resistive flow on color, power and spectral Doppler. Increased vascularity was seen with the low resistive flow in the right and left uterine artery. Endometrium was examined while increasing transmit frequency to 6 MHz but No retained product of conception, were observed and endometrial-myometrial interface clearly appreciated. Previously angiography was used as gold standard for the diagnosis of uterine arteriovenous malformation but Doppler ultrasound is the current gold standard. The Patient attendant was contacted after one week for detail and confirmatory investigations. She allegedly underwent hysterectomy, while she already had three kids. The surgical notes sent by patient attendant confirmed arteriovenous malformation.

Keywords

Arterio-venous malformation; Color doppler; Mosaic blood flow pattern; Power doppler; Sonography; Spectral doppler; Uterine artery waveform

INTRODUCTION

Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM) is a potentially life-threatening condition often results in catastrophic bleeding [1]. Its prevalence is still unknown because it is a rare vascular malformation and very few cases are reported in the literature [2]. AVM is an abnormal and nonfunctional fistula formation between the uterine arteries and veins without intervening capillaries [3]. Although the patients typically present with vaginal bleeding, some patients may supper from massive, life-threatening bleeding in some instances [4]. However, the treatment of choice is hysterectomy but embolization of the malformed arteries and veins could also be done [5]. The management of arterio-venous malformation is multifactorial, depends upon the severity of the hemorrhage, while keeping in mind the fertility status of the patient, sometime conservative management and medical therapy could be preferred [6].

This vascular malformation is an abnormal connection between the veins and arteries, its early and accurate diagnosis, and proper management is utmost important for saving the patient life [7]. However improper diagnosis can lead to the most emergent method of treatment, Dilatation and Curettage (D&C), which can worsen the underlying condition, leading to uterine profusion, hemorrhage, shock and death [8,9]. Various vessels could involve fistula formation in the uterus but usually muscular and thin-walled vessels are more frequently involved in the malformation in varying proportions [8]. Intimal fibrous thickening was commonly seen in the muscular vessels, resulting from elevated intraluminal pressure leading to further increase in intravascular pressure [10]. The bleeding episode might be triggered by hormonal changes occurs in some cases just as pregnancy, menstruation, estrogen and progestin therapy, etc., [11]. Uterine AVMs may either be present in isolation or coexist with other conditions such as retained products of conception [12].

Ultrasound with color and spectral Doppler is the initial imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of AVMs [13]. In many cases, AVMs are diagnosed with ultrasound and confirmed with either angiography or CT scan [14]. All of the imaging modalities are morphologic in nature, but the advantage of ultrasound over other imaging modalities is that it can detect blood flow, the direction of flow and velocity of blood flow, it is therefore preferred to other imaging modalities in the diagnosis of such malformation involving vessels [15]. The diagnosis of AVM only based on grayscale ultrasound imaging is difficult, but Doppler imaging is imperative to its diagnosis [6]. Accurate diagnosis of an arteriovenous malformation is clinically important for the management of patients and rare in incidence, we got a case after a very long time of ultrasound practice. It is, therefore, we present the case for the purpose of awareness, development of knowledge and elucidates the importance of Doppler ultrasound in its diagnosis.

CASE PRESENTATION

We examined a 36-year-old woman sent to Gilani ultrasound center Lahore, with a chief complaint of intermittent hemorrhage for 26 days. One year back she gave birth to her fourth child at full term through normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. The patient was normally recovered, involution was completed. She was breastfeeding her baby that’s why remained normal physiologically, amenorrhoeic. Twenty-six days ago, she felt per-vaginal bleeding and continued for long. She consulted her gynecologist for the complaint of bleeding, that’s why she was referred to the ultrasound clinic for searching out its possible cause. She has never had any history of retained products of conception or Dilation and Curettage (D&C). Her all three healthy babies were vaginally delivered of normal weight and did not have any miscarriages. She has had no history of any type of surgery, interventional procedure or any type of contraceptive device. On physical examination, she was pale and faint but a febrile and her Hemoglobin (Hb) level was 8.5 g/dL. Her Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) level was 1.5mIU/mL.

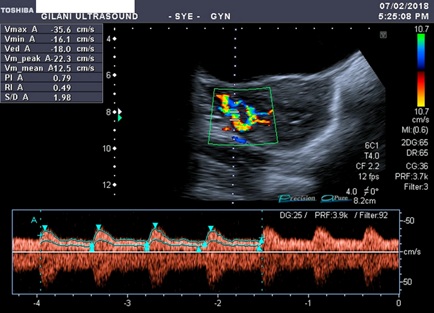

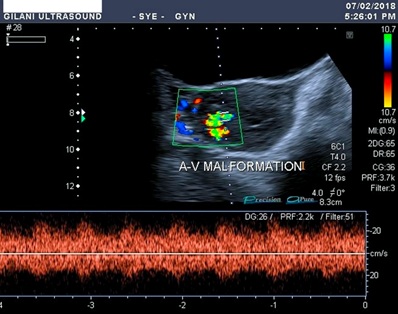

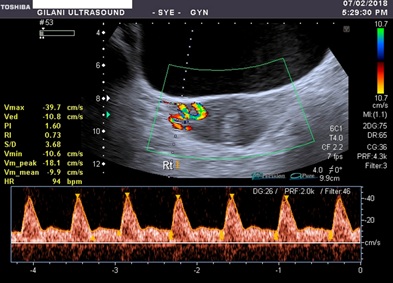

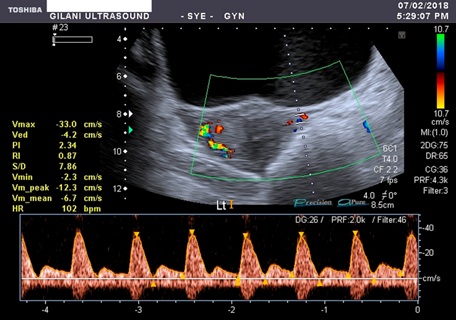

Her gynecological transabdominal ultrasound was performed with a full bladder, following AIUM guidelines. The globular-shaped bulky uterus was observed measuring 8.0 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.7 cm and endometrial thickness 1.3 cm. Prominent vessels were observed on the right lateral wall of the uterus, originated from the anastomosis of the right uterine artery and ovarian artery. On grayscale ultrasound tubular hypoechoic region was seen on the right-side wall of the uterus but increased vascularity was detected on color Doppler with mosaic pattern and aliasing (Figure 1). Spectral Doppler ultrasound showed a very low resistive flow in the malformed vessels Peak Systolic Velocity (PSV) was noted 35.6 cm/s and Resistive Index (RI) 0.49 (Figures 2 and 3). Both the uterine arteries were observed and its flow pattern was low resistive, unlike nongravid uterus having high resistive flow pattern. It appeared that both the uterine arteries are feeding the AVM. Right and left Uterine arterial Peak Systolic Velocity (PSV), End Diastolic Velocities (EDV) and Resistive Index (RI) were 39.7 cm/s, 10.8 cm/s, and 33.0 cm/s, 4.2 cm/s respectively (Figures 4 and 5). The grayscale, color, power and spectral Doppler criteria were confirmatory of AVM. Surgical notes of the hysterectomy confirmed arteriovenous malformation in the right lateral wall of the uterus.

Figure 1: Right side uterine wall AVM, color doppler imaging shows mosaic color pattern with aliasing.

Figure 2: Spectral doppler waveform of the vessels involved in AVM shows low resistive flow. Peak systolic velocity is 35.6 cm/s, end diastolic velocity is 18.0 cm/s, resistive index is 0.49 and pulsatility index is 0.79.

Figure 3: Spectral waveform of the malformed vessels shows low resistive blood flow. There was no difference between the flow pattern of arteries and veins. Pulsatile flow is observed everywhere.

Figure 4: Spectral waveform of the right uterine artery having relatively low resistive and less pulsatile blood flow. Peak systolic velocity is 39.7cm/s, end diastolic velocity is 10.8 cm/s, resistive index is 0.73 and pulsatility index is 1.60.

Figure 5: Spectral waveform of the left uterine artery having relatively high resistive and more pulsatile blood flow. Peak systolic velocity is 33.0 cm/s, end diastolic velocity is 4.2 cm/s, resistive index is 0.87 and pulsatility index is 2.34.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We performed this study at Gilani Ultrasound Center to rule-out the possible cause of per vaginal bleeding. The patient was selected for this research study when examined with unusual findings of multiple tubular hypoechoic appearances on the right side of the uterus. The patient was diagnosed satisfactorily and accurately with diagnostic ultrasound and later on confirmed with surgery. Toshiba Xario with a convex transducer (frequency 3-6MHz) equipped with color, power and spectral Doppler was used for this examination. The procedure was explained to the patient guardian and written informed consent was obtained with the assurance that her personal identity will be kept undisclosed. We performed the procedure according to AIUM protocols, which are routinely observed in this department. We examined the uterus in the supine position with the optimally full bladder. Color, power, and spectral Doppler were applied, cine loops and images were saved in the machine. The dilated vessels with high flow velocity and aliasing were followed to trace its feeding vessels. The feeding vessels were found to be mainly from the anastomosis of the right uterine and ovarian artery.

Surgical notes

AVM was seen on the right-side uterine wall with multiple feeding vessels from right uterine and ovarian arteries and to some extent from the left uterine artery. The diagnosis was confirmed with, hysterectomy performed on 9th February 2018.

DISCUSSION

The uterine arteriovenous malformation is a rare vascular abnormality leading to per-vaginal bleeding, ranging from intermittent to profuse active bleeding. The patient may become unstable due to excessive blood loss (anemia), hypovolemic shock (hemorrhagic shock) and death. It is considered one of the differential diagnosis of prevaginal bleeding in women of reproductive age as well as post-menopausal women [16]. It is reported that AVM was first time introduced in 1926, and after that very few cases are presented in the literature. But it is believed that with the introduction of new sophisticated imaging modalities like high-resolution Doppler ultrasound its incidence could be increased [2,6]. A case of postmenopausal uterine arteriovenous malformation with life-threatening uterine bleeding was presented by E Sato et al., [17]. Uterine arteriovenous malformation accounts for 1-2% of massive vaginal bleeding, and it can be diagnosed satisfactorily by Doppler ultrasound. Some axillary imaging modalities could be used as confirmatory, i.e., magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography and pelvic angiography. A report of postmenopausal uterine arteriovenous malformation was presented with life-threatening uterine bleeding. Initially, the patient was treated with uterine embolization but an emergency hysterectomy was performed after its failure. The hysterectomy was successful, a year after surgery, the patient has had no vaginal bleeding. Hysterectomy was considered comparatively safe and effective therapeutic measure for uterine arteriovenous malformations of postmenopausal women who suffered from with life-threatening uterine bleeding. The case which we presented was during fertile life, she successfully gave birth to four kids and one year after the delivery of her last baby she got Arterio-venous malformation.

Kim I et al., presented a case of Arteriovenous malformation of the uterus, a cause of massive operative bleeding [18]. Clinically, vaginal bleeding is the most common presentation of arteriovenous malformation, therapeutic dilatation and curettage may worsen the condition. The reported case of arteriovenous malformation causing serious bleeding during a hysterectomy. The patient was a 47-year-old multiparous woman who had a history of chronic vaginal bleeding for one year. Numerous anomalous blood vessels draining into the right and left uterine arteries were found on the anterior wall of the uterus and parametrium. In our case, the Doppler findings and the surgical report confirmed that the AVM was feed by right and left uterine arteries as well as aright ovarian artery.

M Cura et al.,; worked on arteriovenous malformations of the uterus he collected a lot of data on this vascular disease [5]. It was summarized that AVMs usually occur during the reproductive age, per-vaginal bleeding and recurrent pregnancy loss are the common presentations of this malformation. AVM may either be congenital or acquired, congenital AVMs are very rare and can develop due to abnormal embryologic differentiation of primitive vascular structures. Congenital AVMs may be developed due to lack of capillary plexus, which results in the direct conduits between arteries and veins without intervening capillary bed [19]. Congenital AVMs may extend beyond the uterine limit into the pelvis and provide blood supply to multiple intrauterine and extrauterine structures [20]. Acquired uterine AVMs are formed in response to traumatic causes of arteriovenous communication include endometrial curettage or pelvic surgery, endometrial instrumentation, contraceptive devices, etc., [21]. Acquired AVMs of the uterus may be related to endometrial cancer or gestational trophoblastic disease [22,23]. Some other conditions i.e., miscarriage, uterine infection, myomas, endometriosis, exposure to diethylstilbestrol, and intrauterine instrumentation and procedures, could also cause AVMs [13,24]. Acquired AVM is the formation of an abnormal communication between the subsidiary branches of the uterine artery and the myometrial venous plexus within myometrium and endometrium [25,26]. Sonographic imaging findings along with patient history are helpful in the differentiation of congenital and acquired arteriovenous malformation [27]. The case we presented having unclear history favoring acquired arteriovenous malformation but the patient age range and normal gravidity and prevaginal deliveries suggesting that she developed acquired-form of AVM.

AVMs may be an asymptomatic mass or it can cause congestive heart failure if the fistula is formed between large vessels and plenty of blood shunts from arteries to veins without intervening capillaries [28]. Endometrial curettage, a procedure commonly performed in patients with abnormal vaginal bleeding, aggravates the genital hemorrhage of a uterine AVM [22,25]. Unlike developing world, the practice of dilatation and curettage is very common in our country, but the said patient has had no history of recent delivery or any miscarriage, it is, therefore, she was sent for investigation before the procedure. Otherwise, in my opinion, and expertise as a medical doctor, dozens of patients having such histories are undergoing procedures and either dies or saved with the expense of uterine lose, while undergoing hysterectomy for the cure of post-procedural catastrophic bleeding.

With reference to a case report published by Hashim and Nawawi; on the Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation [2]. They elucidate the use of ultrasound for the diagnosis of uterine arteriovenous malformation. They published their report on acquired AVM in a patient of childbearing age with secondary postpartum hemorrhage. They accurately diagnosed the patient and confirmed it with Angiography. AVM vascular embolization was successfully performed with polyvinyl alcohol. The post-embolization imaging showed complete cure of the AVM. They encountered no complications and the hemorrhage decreased after the procedure. But along with AVM they found retained product of conception and after some days they carefully removed them with gentle curettage. Another study was published by Kim T et al., with the purpose to evaluate the clinical outcomes of bilateral uterine arteries embolization in the management of AVM [7]. They prolonged their study for 10 years due to the rareness of the disease. During this long period, only twenty patients were enrolled in this procedural study. The clinical success rate of uterine embolization for the management of uterine AVM was estimated as 89.5%. In our case report, the patient was agreed for hysterectomy, the definitive treatment procedure. Now embolization was required and the Doppler ultrasound findings were confirmed by surgical notes.

A case of a 46-year-old female with congenital arteriovenous malformation managed with hysterectomy was reported on by Bhoil R et al., in the polish journal of radiology [28]. She was presented with depressive illness and severe vaginal bleeding smoothly increased from slight spotting. She was suffering from cramping abdominal pain and lethargy, malaise and anemia. Previously, she had a history of multiple episodes of per-vaginal bleeding. She was married and once she became pregnant about two years back but unfortunately the pregnancy was spontaneously terminated at the gestational age of eight weeks, after that she never conceived. She had no history of any uterine instrumentation, surgery or direct uterine trauma. On sonographic examination, multiple anechoic areas were seen in the myometrium mostly in the fundal region of the uterus. Colour Doppler evaluation of the region of interest demonstrated a mixed arteriovenous, mosaic type of blood flow with color aliasing. On spectral waveform, the low was high velocity and low resistance. The rest of the adnexal structures were appeared normal. With the help of these sonographic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with arteriovenous malformation. After a hysterectomy, the specimen of the uterus shows multiple small vessels and proliferative phase uterus. The patient whom we diagnosed was of acquired arteriovenous malformation, the arteries and veins were communicated at a very specific region of the uterus. On ultrasound examination, we observed similar findings but the post-mastectomy microscopic examination showed that the endometrium was at the late secretory phase and the malformation was made in the main mural vessels (arteries and veins). No collateral or excessive proliferation was noted. Our patient was normally conceived and gave birth to four normal babies. In the study mentioned above the uterine AVM was diagnosed only with Doppler ultrasound and the patient was willing for the hysterectomy due to her perimenopausal period. Similarly, we diagnosed the patient with Uterine AVM with the help of Doppler ultrasound and the Patient was willing for a hysterectomy because of the severity of the bleeding problem and secondly she had completed her family by four kids. It is, therefore, we can say that we can diagnose uterine AVM with the help of state of the art of ultrasound modality equipped with all for of Doppler.

CONCLUSION

Ultrasound having color, power and spectral Doppler capability is the modality of choice for the accurate diagnosis of arterio-venous malformation. Meticulous scanning and proper history are utmost important for the accurate diagnosis of uterine arteriovenous malformation. MRI and angiography are the other imaging modality for the diagnose of uterine Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM)

RECOMMENDATION

Ultrasound image has a limited field of view that is why such images are not reproducible, Post-examination expert-opinion on the same image is impossible (Operator dependent). However, to optimize the machine settings, utilize the benefit of real-time sonography, use state of the art modality and improve the operator knowledge can overcome this deficiency.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have any competing interests in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Karadag B, Erol O, Ozdemir O, Uysal A, Alparslan AS, et al. (2016) Successful Treatment of Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation due to Uterine Trauma. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2016: 1890650.

- Hashim H, Nawawi O (2013) Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation. Malays J Med Sci 20: 76-80.

- Yazawa H, Soeda S, Hiraiwa T, Takaiwa M, Hasegawa-Endo S, et al. (2013) Prospective evaluation of the incidence of uterine vascular malformations developing after abortion or delivery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 20: 360-367.

- Vijayakumar A, Srinivas A, Chandrashekar BM, Vijayakumar A (2013) Uterine Vascular Lesions. Rev Obstet Gynecol 6: 69-79.

- Cura M, Martinez N, Cura A, Dalsaso TJ, Elmerhi F (2009) Arteriovenous Malformations of the Uterus. Acta Radiologica 50: 823-829.

- Yoon DJ, Jones M, Taani JA, Buhimschi C, Dowell JD (2016) A Systematic Review of Acquired Uterine Arteriovenous Malformations: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Transcatheter Treatment. AJP Rep 6: 6-14.

- Kim T, Shin JH, Kim J, Yoon HK, Ko GY, et al. (2014) Management of bleeding uterine arteriovenous malformation with bilateral uterine artery embolization. Yonsei Med J 55: 367-373.

- Seo KJ, Kim J, Sohn IS, Kwon HS, Park SW, et al. (2013) Failed transarterial embolization of subserosal uterine arteriovenous malformation. Obstet Gynecol Sci 56: 333-337.

- Scribner D, Fraser R (2016) Diagnosis of Acquired Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation by Doppler Ultrasound. J Emerg Med 51: 168-171.

- Hickey M, Fraser IS (2000) Clinical implications of disturbances of uterine vascular morphology and function. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 14: 937-951.

- Deligeoroglou E, Karountzos V, Creatsas G (2013) Abnormal uterine bleeding and dysfunctional uterine bleeding in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Gynecol Endocrinol 29: 74-78.

- Aziz N, Lenzi TA, Jeffrey RB Jr, Lyell DJ (2004) Postpartum uterine arteriovenous fistula. Obstet Gynecol 103: 1076-1078.

- Timmerman D, Wauters J, Van Calenbergh S, Van Schoubroeck D, Maleux G, et al. (2003) Color Doppler imaging is a valuable tool for the diagnosis and management of uterine vascular malformations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 21: 570-577.

- Aiyappan SK, Ranga U, Veeraiyan S (2014) Doppler Sonography and 3D CT Angiography of Acquired Uterine Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs): Report of Two Cases. J Clin Diagn Res 8: 187-189.

- Coatney RW (2001) Ultrasound imaging: principles and applications in rodent research. ILAR J 42: 233-247.

- Pacagnella RC, Souza JP, Durocher J, Perel P, Blum J, et al. (2013) A systematic review of the relationship between blood loss and clinical signs. PLoS One 8: 57594.

- Sato E, Nakayama K, Nakamura K, Ishikawa M, Katagiri H, et al. (2015) A case with life-threatening uterine bleeding due to postmenopausal uterine arteriovenous malformation. BMC Womens Health 15: 10.

- Kim I, Ha SY, Yoon SA, Lee KW (1991) Arteriovenous malformation of the uterus--a cause of massive operative bleeding. J Korean Med Sci 6: 187-190.

- Huang MW, Muradali D, Thurston WA, Burns PN, Wilson SR (1998) Uterine arteriovenous malformations: gray-scale and Doppler US features with MR imaging correlation. Radiology 206: 115-123.

- Ghai S, Rajan DK, Asch MR, Muradali D, Simons ME, et al. (2003) Efficacy of embolization in traumatic uterine vascular malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol 14: 1401-1408.

- Guan D, Wang J, Zong L, Li S, Zhang YZ (2017) Acquired uterine arteriovenous fistula due to a previous cornual pregnancy with placenta accreta: A case report. Exp Ther Med 13: 2801-2804.

- O'Brien P, Neyastani A, Buckley AR, Chang SD, Legiehn GM (2006) Uterine Arteriovenous Malformations: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 25: 1387-1392.

- Farias MS, Santi CC, Lima AA, Teixeira SM, De Biase TC (2014) Radiological findings of uterine arteriovenous malformation: A case report of an unusual and life-threatening cause of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Radiol Bras 47: 122-124.

- Kurjak A, Chervenak FA (2017) Donald School Textbook of Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynaecology. JP Medical Ltd, London, UK.

- Evans A, Gazaille III RE, McKenzie R, Musser M, Lemming R, et al. (2017) Acquired uterine arteriovenous fistula following dilatation and curettage: An uncommon cause of vaginal bleeding. Radiol Case Rep 12: 287-291.

- Kim SM, Ahn HY, Choi MJ, Kang YD, Park JW, et al. (2016) Uterine arteriovenous malformation with positive serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin: Embolization of both uterine arteries and extra-uterine feeding arteries. Obstet Gynecol Sci 59: 554-558.

- Honemeyer U, Alkatout I, Kupesic-Plavsic S, Pour-Mirza A, Kurjak A (2013) The Value of Color and Power Doppler in the Diagnosis of Ectopic Pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 7: 429-439.

- Bhoil R, Raghuvanshi V, Basavaiah S (2015) A case of congenital uterine arterio-venous malformation managed by hysterectomy. Pol J Radiol 80: 202-205.

Citation: Gilani SA, Bacha R, Manzoor I (2020) Sonographic Presentation of Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM). J Non Invasive Vasc Invest 5: 018.

Copyright: © 2020 Syed Amir Gilani, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.