Journal of Nephrology & Renal Therapy Category: Clinical

Type: Case Report

Spontaneous Perinephric Hematoma with Newer Oral Anticoagulation in Kidney Transplant Recipient

*Corresponding Author(s):

Sandesh ParajuliDepartment Of Medicine, Division Of Nephrology, University Of Wisconsin School Of Medicine And Public Health, Madison, WI 53705, United States

Tel:+1 6082650152,

Email:sparajuli@medicine.wisc.edu

Received Date: Dec 30, 2015

Accepted Date: Feb 11, 2016

Published Date: Feb 26, 2016

Abstract

There is limited data about bleeding complications of Newer Oral Anticoagulation (NOAC), dabigatran in kidney transplant recipients. We presented a case of 65 year old, stable kidney transplant recipient, who had kidney transplant in 1990. Patient was transferred from the outside hospital with spontaneous perinephric hematoma likely attributed to the NOAC, dabigatran. He presented to the emergency room with sudden onset of right flank pain and low urine output. On investigation he was found to have acute kidney injury, significant hyperkalemia requiring acute hemodialysis and significant fall in hemoglobin and hematocrit. A non-contrast CT scan of abdomen and pelvis confirmed the diagnosis with large retroperitoneal hematoma (33 cm × 15.3 cm × 11.6 cm), with mass effect. After discontinuation of dabigatran and with conservative management his symptoms improved, his renal function returned to the base line and repeat CT scan after eight weeks showed a significant improvement in right retroperitoneal hematoma with only a small residual collection, and no mass in the native or transplanted kidney. Direct thrombin inhibitors, dabigatran, and the direct Factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban are newer oral anticoagulants. Dabigatran is a reversible inhibitor of Factor IIa (thrombin) with a half-life of 12 to 17 hours. When compared to the traditional therapy with warfarin, these agents have the advantage of not requiring regular blood draws for monitoring along with minimal food and drug interactions. Renal dose adjustment is very important with NOACs as these medications are cleared by the kidneys to the variable extent. Kidney transplant recipients represent a special subset of patients who are on immunosuppressive medications, susceptible to fluctuations in renal function and may be at higher risk of bleeding. More studies are needed to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of NOAC in this sub group of patients, as use of NOACs is rising.

Keywords

Kidney Transplant

ABBREVIATIONS

DTIs : Direct Thrombin Inhibitors

DVT : Deep Vein Thrombosis

Hb : Hemoglobin

NOAC : New Oral Anti-coagulants

PE : Pulmonary Embolism

P-gp : P-glycoprotein

VTE : Venous Thromboembolism

VKA : Vitamin K Antagonist

DVT : Deep Vein Thrombosis

Hb : Hemoglobin

NOAC : New Oral Anti-coagulants

PE : Pulmonary Embolism

P-gp : P-glycoprotein

VTE : Venous Thromboembolism

VKA : Vitamin K Antagonist

CASE PRESENTATION

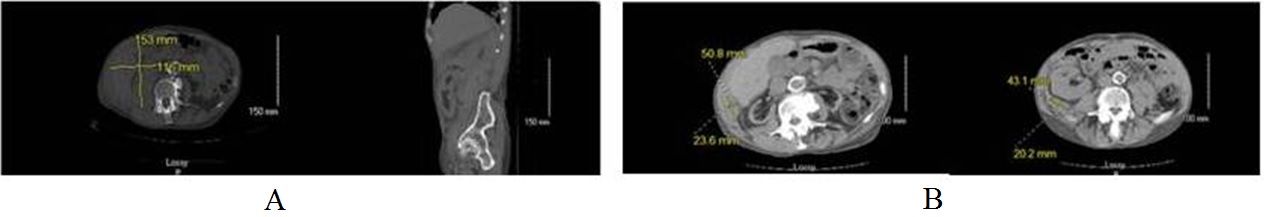

A 65 year old man with a history of end stage renal disease of unknown etiology and a kidney transplantation in 1990 presented to the emergency room with complaints of sudden onset right flank pain along with low urine output for a few days. In addition to dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, his other home medications included clonidine, atenolol, nifedipine, furosemide, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Vital signs were stable on presentation. His serum creatinine at presentation was 3.39 mg/dl from baseline creatinine of 1.4 to 1.6 mg/dl; serum potassium was 7.7 mEq/dl (normal 3.5 to 5.1 mEq/dl); and Hemoglobin (Hb) was 7.5 gm/dl (prior Hb was 10.9 gm/dl). A non-contrast CT scan of abdomen and pelvis showed a large retroperitoneal hematoma (33 cm × 15.3 cm × 11.6 cm). Mass effect on the surrounding retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal structures extending into the pelvis pushed the transplanted kidney forward, causing minimal upper pole collecting system dilation without hydronephrosis (Figure 1A). There was no history of trauma or recent kidney biopsy, which are known risk factors for intra-abdominal hematoma. He received emergent hemodialysis for hyperkalemia and was aggressively transfused with packed red blood cells along with prothrombin complex concentrate. He was managed conservatively with a stabilization of hemoglobin and recovery of renal function towards the baseline within a week. A repeat CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained at eight weeks, which showed a significant improvement in right retroperitoneal hematoma with only a small residual collection, and no mass in the native or transplanted kidney (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: (A) Large perinephric hematoma and hematoma extending from the diaphragm to pelvic inlet. (B) Repeat CT scan abdomen in eight weeks showed significant improvement in the hematoma. Two small residual hematomas (measuring 4.3 cm × 2.0 cm located posterior to the right transplant kidney and 5.1 cm × 2.4 cm in the right lateral abdominal wall).

DISCUSSION

There have been very few case reports and post-marketing surveillance data of dabigatran causing spontaneous intra-abdominal hematoma and hyperkalemia, especially in patients with renal insufficiency [1]. Our patient had significant life threatening hyperkalemia, which could be due to the medication itself or likely related to the large hematoma. To our knowledge, this is the first case of a renal transplant recipient with spontaneous hematoma on NOACs.

Direct Thrombin Inhibitors (DTIs), dabigatran, and the direct Factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban are newer oral anticoagulants that were approved for the treatment of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in October 2010 and Venous Thromboembolism (VTE), specifically Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE), in April 2014.

When compared to traditional therapy with warfarin, these agents have the advantage of not requiring regular blood draws for monitoring along with minimal food and drug interactions [2]. The major drawback of these agents is absence of a reversal agent in cases of clinically significant bleeding, although the FDA has recently approved a reversal agent, idarucizumab (Praxbind), for emergent or life-threatening bleeding associated with dabigatran [3].

Renal dose adjustment is very important with New Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) as these medications are cleared by the kidneys to variable extent (about 30% for apixaban and rivaroxaban and up to 85% for dabigatran) [2]. The product inserts for these drugs recommends avoiding use in the patients with creatinine clearance of less than 15 ml/min.

Dabigatran is a reversible inhibitor of Factor IIa (thrombin) with a half life of 12 to 17 hours [4]. Inhibition of factor IIa prevents conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin and cross-linking of fibrin clot [4]. It is a substrate of the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp) which affects absorption of the prodrug [4]. There is a potential of increased drug exposure and bleeding risk with concomitant exposure to P-gp inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporine, carvedilol, amiodarone etc.) [4]. About 80% of the drug elimination is via kidneys [4].

Dabigatran has shown non-inferiority to warfarin for the treatment of VTE, along with reduction of major bleeding [5]. However, there is very limited information on special subgroups such as patients with renal impairment, cancer or fragile patients, who may be at higher risk of bleeding [5].

Dabigatran showed non-inferiority in reduction of recurrent VTE when compared with warfarin in RE-COVER trial [2.4% vs 2.2% Hazard Ratio (HR) 1.1, 95% CI = 0.65 -1.84; P < 0.001] [2]. A similar trend was observed in RE-COVER 2 trial [2.3 vs 2.2%; HR = 1.08; 95% CI 0.45 -1.48] [2,5].

In both of these studies, dabigatran had similar rates of bleeding when compared with warfarin [RE-COVER trial (1.6% vs 1.9%; HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.45 -1.48); RE-COVER 2 trial (1.2% vs 1.7%; HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.36 - 1.32)] [2,5].

A pooled analysis of these studies consisting of about 5100 patients showed results consistent with the individual studies with similar benefit risk profile, irrespective of renal insufficiency and cancer; however, there is no data on clinical risks in kidney transplant recipients [5]. Also, these studies excluded patients with severe renal insufficiency. The drug should be used cautiously in patients with fluctuating renal function and advanced kidney disease [4]. Both the clinical efficacy and risk of bleeding increases with age [5]. Data from RE-LY trial shows a higher bleeding risk in patients aged 75 and above [4].

Our patient was on cyclosporine (P-gp inhibitor) which may have increased the bleeding risk with dabigatran. Initial CT angiogram was negative for ruptured arterial aneurysm or pseudo-aneurysm. Also, there was no evidence of renal/adrenal mass on repeat CT scan.

Direct Thrombin Inhibitors (DTIs), dabigatran, and the direct Factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban are newer oral anticoagulants that were approved for the treatment of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in October 2010 and Venous Thromboembolism (VTE), specifically Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE), in April 2014.

When compared to traditional therapy with warfarin, these agents have the advantage of not requiring regular blood draws for monitoring along with minimal food and drug interactions [2]. The major drawback of these agents is absence of a reversal agent in cases of clinically significant bleeding, although the FDA has recently approved a reversal agent, idarucizumab (Praxbind), for emergent or life-threatening bleeding associated with dabigatran [3].

Renal dose adjustment is very important with New Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) as these medications are cleared by the kidneys to variable extent (about 30% for apixaban and rivaroxaban and up to 85% for dabigatran) [2]. The product inserts for these drugs recommends avoiding use in the patients with creatinine clearance of less than 15 ml/min.

Dabigatran is a reversible inhibitor of Factor IIa (thrombin) with a half life of 12 to 17 hours [4]. Inhibition of factor IIa prevents conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin and cross-linking of fibrin clot [4]. It is a substrate of the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp) which affects absorption of the prodrug [4]. There is a potential of increased drug exposure and bleeding risk with concomitant exposure to P-gp inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporine, carvedilol, amiodarone etc.) [4]. About 80% of the drug elimination is via kidneys [4].

Dabigatran has shown non-inferiority to warfarin for the treatment of VTE, along with reduction of major bleeding [5]. However, there is very limited information on special subgroups such as patients with renal impairment, cancer or fragile patients, who may be at higher risk of bleeding [5].

Dabigatran showed non-inferiority in reduction of recurrent VTE when compared with warfarin in RE-COVER trial [2.4% vs 2.2% Hazard Ratio (HR) 1.1, 95% CI = 0.65 -1.84; P < 0.001] [2]. A similar trend was observed in RE-COVER 2 trial [2.3 vs 2.2%; HR = 1.08; 95% CI 0.45 -1.48] [2,5].

In both of these studies, dabigatran had similar rates of bleeding when compared with warfarin [RE-COVER trial (1.6% vs 1.9%; HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.45 -1.48); RE-COVER 2 trial (1.2% vs 1.7%; HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.36 - 1.32)] [2,5].

A pooled analysis of these studies consisting of about 5100 patients showed results consistent with the individual studies with similar benefit risk profile, irrespective of renal insufficiency and cancer; however, there is no data on clinical risks in kidney transplant recipients [5]. Also, these studies excluded patients with severe renal insufficiency. The drug should be used cautiously in patients with fluctuating renal function and advanced kidney disease [4]. Both the clinical efficacy and risk of bleeding increases with age [5]. Data from RE-LY trial shows a higher bleeding risk in patients aged 75 and above [4].

Our patient was on cyclosporine (P-gp inhibitor) which may have increased the bleeding risk with dabigatran. Initial CT angiogram was negative for ruptured arterial aneurysm or pseudo-aneurysm. Also, there was no evidence of renal/adrenal mass on repeat CT scan.

CONCLUSION

There are very limited data on effect of newer oral anticoagulants in kidney transplant recipients on immunosuppression. Also, there is limited information on risk of spontaneous intra-abdominal hematoma with NOACs in this group of patients. Kidney transplant recipients represent a special subset of patients who are on immunosuppressive medications, susceptible to fluctuations in renal function and may be at higher risk of bleeding due to associated co-morbid conditions such as cardiac disease on antiplatelet treatment or uncontrolled hypertension, higher age due to prolonged survival and allograft dysfunction with increased risk of uremic bleeding. We presented the unusual case of spontaneous intra-abdominal hematoma in a renal transplant recipient which is likely due to the newer oral anticoagulation medication.

More studies are needed to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of non-VKA anticoagulants in this subgroup of patients, as use of NOACs is rising.

More studies are needed to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of non-VKA anticoagulants in this subgroup of patients, as use of NOACs is rising.

REFERENCES

- Zaleski M, Dabage N, Paixao R, Muniz J (2013) Dabigatran-induced hyperkalemia in a renal transplant recipient: a clinical observation. J Clin Pharmacol 53: 456-458.

- Schulman S, Kakkar AK, Goldhaber SZ, Schellong S, Eriksson H, et al. (2014) Treatment of acute venous thromboembolism with dabigatran or warfarin and pooled analysis. Circulation 129: 764-772.

- Burness CB (2015) Idarucizumab: First Global Approval. Drugs 75: 2155-2161.

- Iyer V, Singh HS, Reiffel JA (2012) Dabigatran: comparison to warfarin, pathway to approval, and practical guidelines for use. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 17: 237-247.

- Prandoni P (2014) Treatment of patients with acute deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism: efficacy and safety of non-VKA oral anticoagulants in selected populations. Thromb Res 134: 227-233.

Citation: Saxena N, Parajuli S (2016) Spontaneous Perinephric Hematoma with Newer Oral Anticoagulation in Kidney Transplant Recipient. J Nephrol Renal Ther 2: 002.

Copyright: © 2016 Sandesh Parajuli, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!