Subtotal Colectomy with Ileostomy, Surgical Management of Ischemic Colitis: A Case Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Fahim SoukhakDepartment Of Surgery, Ross University School Of Medicine, Los Angeles, United States

Email:FahimSoukhak@mail.rossmed.edu

Abstract

Ischemic colitis (IC) occurs when blood flow to part of the colon is temporarily reduced. Most patients with IC usually have some associated comorbidities that affect mucosal perfusion. A long history of diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, atrial fibrillation, hypotension, and chronic kidney disease are comorbidities that need to be carefully considered in the diagnosis and management of the patient with IC. IC commonly manifests with a clinical trio of symptoms including abdominal pain, hematochezia, and diarrhea. Most cases are mild and self-limiting with a good prognosis, responding well to medical management including antibiotics and bowel rest; however, some dire situations may require surgical intervention. This case report will discuss clinical presentations, risk factors, diagnosis, and surgical treatment (subtotal colectomy with ileostomy) in a 50-year-old female patient with IC.

Introduction

Ischemic colitis (IC), the most common type of gastrointestinal ischemia, results from either severely decreased colonic perfusion or subsequent reperfusion damage [1]. The most typical location for IC is the splenic flexure, but any part of the colon might be impacted. Because of its robust collateral circulation, the rectum is comparatively unaffected [2]. Research states an incidence of 7.3 to 18 cases per 100,000 of the population [3,4]. The length and severity of hypo perfusion determine whether the colonic injury is predominantly ischemic or due to reperfusion. Unspecific warning symptoms or signs, such as lower abdomen pain and bleeding, particularly rectal bleeding, ileus, fever, widespread peritonitis, or shock, are typically present when it first manifests [5]. In less severe ischemia, patients may experience bloody diarrhea that is not accompanied by abdominal pain while in more severe cases abrupt extreme abdominal pain and tenderness (often out of proportion), fever, and leukocytosis are characteristic. Systemic toxicity or peritonitis are indications of full-thickness necrosis and perforation. Ischemic colitis manifests in two main ways: gangrenous (transmural colonic necrosis), which typically requires surgery and has poor prognoses, and transient (reversible lesions of hypo perfusion to mucosa or submucosa), which has fewer problems and typically responds well to medical treatment. Risk factors include vascular disease, atherosclerosis, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, vasculitis, hypotension, constipation-inducing drugs, immunomodulatory, illicit drugs, and tobacco use [6]. The risk is higher for those who require renal replacement therapy, particularly because hemodialysis can cause microvascular damage and periods of hypotension [7,8]. The mainstays of therapy are bowel rest and broad-spectrum antibiotics, approximately 80% of patients usually recover with this regimen. Optimizing hemodynamic parameters is important, particularly if hypotension is the underlying cause. Stricture (10%-15%) and chronic segmental ischemia (15%-20%) are examples of long-term consequences. Failure to improve after two to three days of medical management, progression of symptoms, or deterioration in clinical condition are indications for surgical exploration [9-10].

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old female patient presented to the ED with altered mental status and hypotension five minutes into her dialysis session. She did not recall anything and felt confused. The patient complained of moderate abdominal pain and denied any fever, nausea, vomiting, numbness or weakness, or rashes. On GI exam abdomen was non-distended, soft with diffuse low-grade abdominal tenderness, normoactive bowel sounds, and no sign of rebound tenderness or guarding. CT of the abdomen showed areas of mild transverse colon wall thickening with gas present within the adjacent mesenteric venous structures which are suggestive of ischemic colitis. No evidence of bowel obstruction, perforation, or bowel wall pneumatosis is seen at this time. On surgical consultation, the patient stated a history of hypertension, long-standing diabetes, and end-stage renal disease with hemodialysis, cesarean, and cholecystectomy. She endorsed normal bowel movement, passing flatus, and denied having bloody stool with a good appetite. On physical examination, the abdomen was distended with an incisional hernia and tympanic with normal bowel sounds.

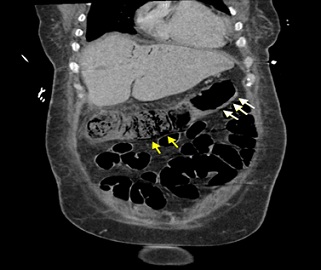

The patient had tenderness to deep palpation to the right lower quadrant without any sign of acute abdomen or peritonitis. Surgical consultation concluded abdominal pain secondary most likely to colitis with no evidence of ischemia based on clinical exam. Medical management was recommended. Shortly after, symptoms deteriorated to a tender abdomen at which point surgical consultation was requested again. CT demonstrated ascending through mid-transverse colon pneumatosis, mesenteric venous, and intrahepatic portal venous air consistent with ischemia and worrisome for associated infarction (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Coronal Abdominal CT Scan depicting worsening pneumatosis (yellow arrows) including the ascending through the transverse colon and circumferential wall thickening (white arrows) from splenic flexure through the rectum.

Figure 1: Coronal Abdominal CT Scan depicting worsening pneumatosis (yellow arrows) including the ascending through the transverse colon and circumferential wall thickening (white arrows) from splenic flexure through the rectum.

The decision was made to take the patient to surgery for exploratory laparotomy. During exploratory laparotomy, obvious ischemia of the transverse colon, as well as the ascending and descending colon, were observed (Figure 2). Subtotal colectomy with diverting ileostomy was performed due to the extent of large bowel necrosis. Hartmann pouch was installed to bring the distal ileum through the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. Post-operative recovery continued to progress without complication with diet advancing on day three.

Figure 2: The gross image of the resected colon with ischemic colitis and focal pseudomembranous colitis on the transverse colon and distal resection margin.

Figure 2: The gross image of the resected colon with ischemic colitis and focal pseudomembranous colitis on the transverse colon and distal resection margin.

Discussion

The primary cause of IC is assumed to be local hypo perfusion and reperfusion damage; however, IC can also originate from changes in the systemic circulation or from anatomical or functional abnormalities in the mesenteric vasculature. The majority of the time, no particular cause of ischemia is found which is explained as localized no occlusive ischemia, likely brought on by the small-vessel disease. Type I disease is conferred to this group. In contrast, the cause of Type II disease is known and typically occurs after a period of systemic hypotension, decreased cardiac output, or aortic surgery. The control of chronic renal impairment was the most significant risk factor for ischemic colitis in our patient. A number of risk factors for ischemic colitis have been linked to chronic kidney disease, including peripheral vascular disease and transitory hypotension (hemodialysis patients. CT with contrast is the preferred choice of imaging study to determine the location and stage of colitis. The presence of transmural colonic infarction can be identified by the CT or MRI findings of colonic pneumatosis, thickening of the intestine wall, edema, thumb printing, and Porto-mesenteric venous gas. Traditional splanchnic angiography should be considered in a patient with signs of acute mesenteric ischemia and negative CT for vascular occlusive disease [11-12].

Patients should receive collaborative gastroenterology and surgical advice because the management of IC includes both medical and surgical components. The focus is on medical management in mild cases without factors that indicate surgical intervention, such as male gender, pre-existing renal dysfunction, history of atrial fibrillation, peritoneal signs, absence of rectal bleeding, and free intraperitoneal fluid. However, in equivocal cases or when a surgical intervention seems necessary, periodic surgical evaluations are required to decide the best timing for operation. The rates of morbidity and mortality following surgery for ischemic colitis are still notably high. Although it is a challenging decision, early diagnosis and prompt surgical intervention for patients with transmural ischemic colitis may improve outcomes. Variables that exhibited significance for mortality on logistic regression analysis include advanced age, impaired functional status, coexisting medical conditions, septic shock, blood transfusion, acute renal failure, and the length of time between hospital admissions to surgery [13].

Conclusion

IC commonly manifests with a clinical trio of symptoms including abdominal pain, hematochezia, and diarrhea. Most cases are mild and self-limiting with a good prognosis. Our patient however presented with atypical symptoms in which she only complained of abdominal pain all through the admission without any other sign of bleeding, or diarrhea while tolerating oral intake just before acute exacerbation of the abdominal pain. Our decision to implement the procedure was further confirmed by the second CTAP study after the episode of acute abdomen. The importance of putting all the indications including patient signs and symptoms, significant past medical history, precise physical exam, and imaging studies couldn’t be emphasized more in the diagnosis of severe IC and a surgical indication of the condition to reduce patient morbidity and mortality.

References

- Uchida T, Matsushima M, Orihashi Y, Dekiden-Monma M, Mizukami H, et al. (2018) A case-control study on the risk factors for ischemic colitis. The Tokai Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine. 43: 111-116.

- Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Kao LS, et al. (1976) Schwartz's Principles of Surgery, 11e. McGraw Hill Education, USA.

- Yngvadottir Y, Karlsdottir BR, Hreinsson JP, Ragnarsson G, Mitev RUM, et al. (2017) The incidence and outcome of ischemic colitis in a population-based setting. Scand J Gastroenterol. 52: 704-710.

- Demetriou G, Nassar A, Subramonia S (2020) The pathophysiology, presentation and management of ischaemic colitis: a systematic review. World J Surg. 44: 927-938.

- Feuerstadt P, Brandt LJ (2010) Colon ischemia: recent insights and advances. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 12: 383-390.

- Brandt LJ, Feuerstadt P, Longstreth GF, Boley SJ (2015) American College of Gastroenterology: ACG clinical guideline: epidemiology, risk factors, patterns of presentation, diagnosis, and management of colon ischemia (CI). Am J Gastroenterol. 110: 18-44.

- Kalman RS, Pedrosa MC (2015) Evidence-based review of gastrointestinal bleeding in the chronic kidney disease patient. Semin Dial. 28: 68-74.

- Fernández JC, Calvo NL, Vázquez EG, García MJG, Pérez MTA, et al. (2010) Risk factors associated with the development of ischemic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 16: 4564-4569.

- Ryoo SB, Oh HK, Ha HK, Moon SH, Choe EK, et al. (2014) The outcomes and prognostic factors of surgical treatment for ischemic colitis: what can we do for a better outcome?. Hepatogastroenterology. 61: 336-342.

- Tseng J, Loper B, Jain M, Lewis AV, Margulies DR, et al. (2017) Predictive factors of mortality after colectomy in ischemic colitis: an ACS-NSQIP database study. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2: e000126.

- Milone M, Di Minno MND, Musella M, Maietta P, Iaccarino V, et al. (2013) Computed tomography findings of pneumatosis and portomesenteric venous gas in acute bowel ischemia. World J Gastroenterol. 21: 6579-6584.

- Schieda N, Fasih N, Shabana W (2013) Triphasic CT in the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischaemia. Eur Radiol. 23: 1891-1900.

- Hung A, Calderbank T, Samaan MA, Plumb AA, Webster G (2019) Ischaemic colitis: practical challenges and evidence-based recommendations for management. Frontline Gastroenterol. 12: 44-52.

Citation: Soukhak F, Urayeneza O, Grasso SA (2023) Subtotal Colectomy with Ileostomy, Surgical Management of Ischemic Colitis: A Case Study. J Clin Stud Med Case Rep 10:187.

Copyright: © 2023 Fahim Soukhak, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.