Success of Medically Necessary Bilateral Salpingo - Oophorectomy without Uterine Manipulator or Urinary Catheter

*Corresponding Author(s):

Anton TutoveanuUniversity Of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, Australia

Email:anton.tutoveanu@student.uts.edu.au

Abstract

A report of a young adult, transgender male patient who under- went removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes, medically known as bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The procedure was effectively performed without the use of a uterine manipulator or urinary catheter using laparoscopic surgical techniques. These invasive and often humiliating instruments were easily avoided without impacting the risk of complication. Both the skill of the surgeon and intent preparation of the patient made this a successful procedure.

Keywords

Case report; Gynaecology; Key-hole; Laparoscopic; Minimally invasive surgery; Oophorectomy

Introduction

Urinary catheters [1-4] and uterine manipulators [5-9] have been documented to be “essential” instruments in performing pelvic sur- gical procedures. Laparoscopic surgeons are routinely balancing out the risks of these surgeries and their patients’ preferences [10]. Al- though the absence of uterine manipulators and urinary catheters are not entirely novel [4,11-13], the currently available material either lacks details on the exact necessity of these instruments or the infor- mation is unknown, divided, obscure, or utterly false. Patients with gender dysphoria [14], young girls [15,16] sexual assault victims [17- 19] or psychologically sensitive individuals [20] have the right to be treated in the least traumatic and most dignified way possible. This paper documents one of many successful clinical cases where a pelvic operation was performed without any insertion of a urinary catheter or uterine manipulator in the genital region.

Patient Background

Overview & Symptoms 24 year old transgender male suffering from painful periods from a young age (since 12 years old). Has been taking testosterone Hormone Replacement Therapy since 17 years of age where periods ceased. HRT was paused for 6 months in Jan-Jul 2018 (20 years old). Menstruation returned as expected. HRT was recommenced and patient has since been on continuous testosterone treatment for 4 years. Periods however never ceased and have been heavy, painful but regular. Having no future desire for pregnancy, pa- tient has been seeking a surgical solution since 20 years of age.

Diet & Lifestyle Vegan, gluten-free, exercises regularly.

Physical Health BMI in healthy range (20.3). Has had no previous surgeries or other known co-existing physical health problems. His- tory of low iron (either due to heavy periods or diet - undetermined).

Mental Health Diagnosed high-functioning autism[1], psychologically sensitive but generally mentally healthy.

Previous Treatments First-line ineffective treatments from past spe- cialists included tranexamic acid, ibuprofen and progestin (Visanne®) [21]. Intrauterine Devices (IUD) were also suggested. Estrogen based birth control were also deemed unsuitable due to impacting on the patient’s HRT. A surgical intervention was concluded to be the most pertinent option resulting in a permanent solution.

Diagnostics Previous pelvic ultrasound from 10th December 2020 had shown no abnormalities (Figure 1).

Prognosis Endometriosis was likely to be expected.

Figure 1: Ultrasound of the Pelvis from December 2020.

Figure 1: Ultrasound of the Pelvis from December 2020.

[1] Autistic individuals are known to be psychologically sensitive.

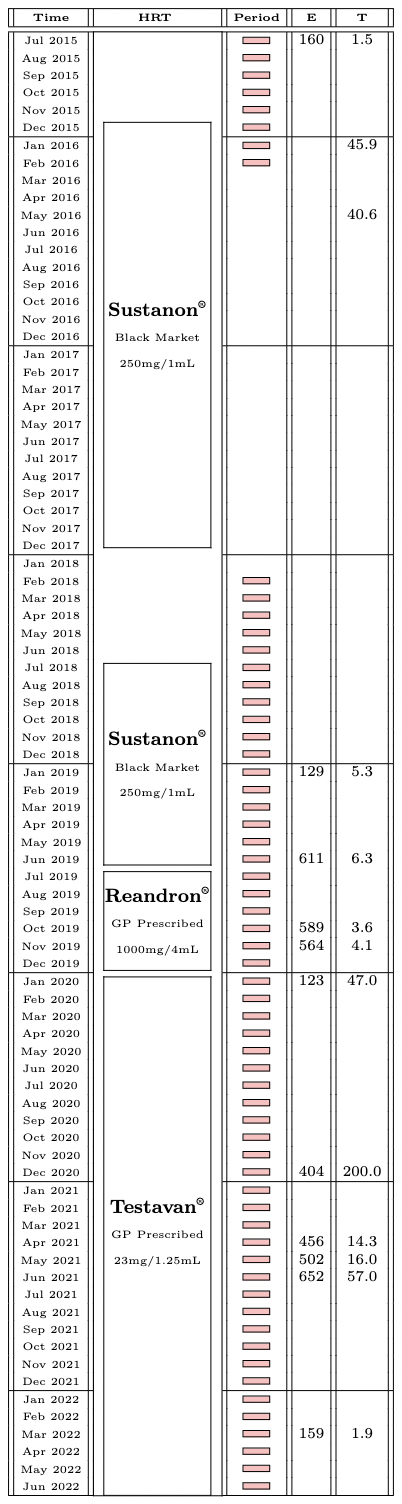

Historical Blood Results

Compiled is a table with all previous blood test results regarding hormone levels, in chronological comparison with HRT used and whether periods were occurring at the time (Table 1).

Table1: Hormone Levels & Periods

Table1: Hormone Levels & Periods

Reproductive hormone levels were tested on the Siemens diagnostic immunoassay from various Australian pathology providers [22- 24]. Reference intervals supplied by these laboratories for an adult male are listed (Table 2).

|

Hormone |

Min. |

Max. |

Unit |

|

Oestradiol |

0 |

190 |

pmol/L |

|

Testosterone |

11.5 |

32.0 |

nmol/L |

Table 2: Estrogen & Testosterone Male Ranges

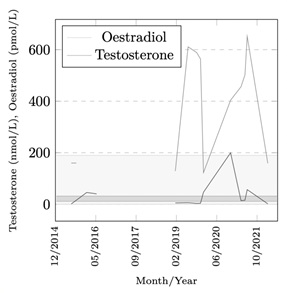

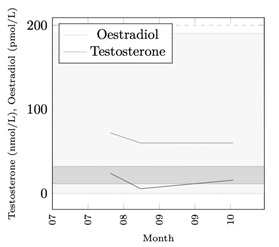

The patient's values with hormone ranges are visualised (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Estrogen & Testosterone Graph

Figure 2: Estrogen & Testosterone Graph

The recorded values between Jan 2019 to Mar 2022 show unstable and extreme spikes in both reproductive hormones. This was likely due to a conversion of excess testosterone and a competing production of estrogen from the ovaries. Transgender patients are known to have difficulty finding the optimal amount of HRT for their bodies [25].

Procedure

The removal of at least estrogen producing organs – both ovaries, was expected to solve the cessation of periods and prevent production of estrogen which the testosterone was not suppressing. Also advised was removing the fallopian tubes to reduce future risk of cancer development [26].

Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy

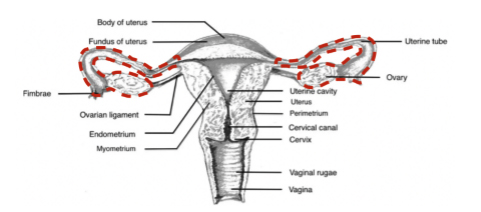

Figure 3: The removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes.

Figure 3: The removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes.

A full hysterectomy was suggested but would mean a longer healing time and a slightly more complex surgery. Both the surgeon and patient agreed that laparoscopic removal of ovaries along with the fallopian tubes would be the most minimally invasive treatment option – a procedure medically known as bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Preferences No urinary catheter, no uterine manipulator, no overnight hospital stay [27].

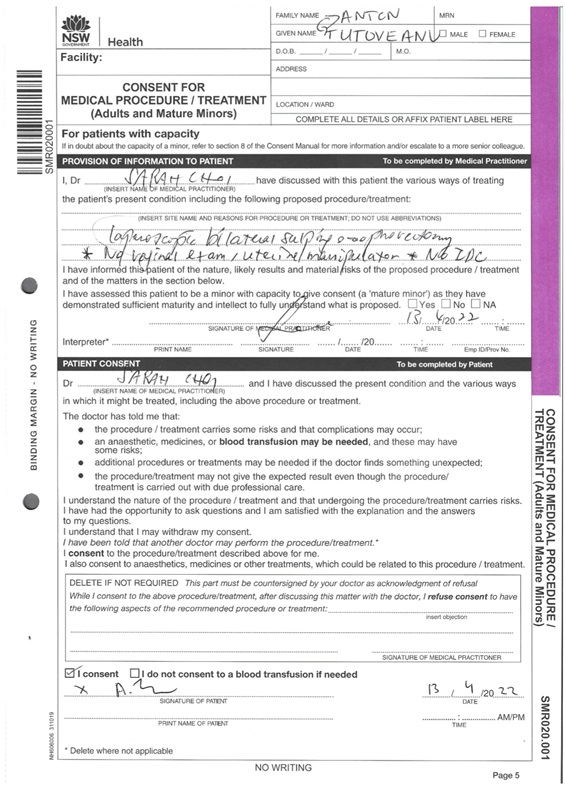

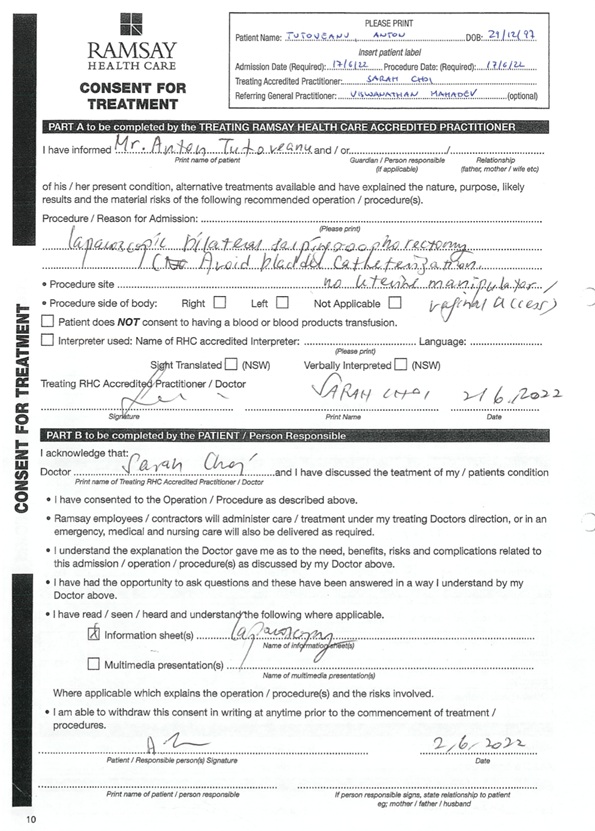

Risks Modern day pelvic surgical operations carry low risk of complications [28]. For this patient’s age, health, condition and the surgeon’s experience, the risks involved in performing such procedure were basically zero. Two studies cited earlier each report back on a large number of pelvic operations that were successfully performed without a uterine manipulator. A. Kavallaris, et. al. reported on 67 total laparoscopic hysterectomies between 2008-2009 without any uterine manipulation having zero complications [12]. While D. Zygouris, et. al. reported on 1023 cases between 2011-2020 of the exact same procedure having zero conversions of laparoscopy to laparotomy [13]. After two appointments with the surgeon, the patient felt confident in the procedure and went ahead with scheduling an operation date on Friday 17th June 2022. The consent form was concisely filled out as attached in the appendices.

Cost Estimate

Residing in New South Wales, Australia the patient had the option to select to undertake the procedure in a public or private hospital [29]. Public route meant being on a waitlist for one year and having the costs covered by the Australian government Medicare system. While private route meant a shorter wait period (about 1-2 months) and fees were the responsibility of the patient or a private health insurer. The patient weighed out the benefits of both routes and selected the private hospital as a self-funded patient. Entire costs of appointments, procedure fees, anaesthesia, hospital facilities and pharmaceuticals including all Medicare rebates in 2022 [30] are listed (Table 3).

|

Date |

# |

Item |

Cost |

|

2022 Apr 13 2022 Apr 13 2022 Apr 26 2022 Apr 26 2022 May 16 2022 Jun 02 2022 Jun 02 2022 Jun 03 2022 Jun 03 2022 Jun 03 2022 Jun 17 2022 Jun 17 2022 Jun 23 2022 Jun 27 2022 Jun 27 2022 Jul 18 2022 Jul 18 2022 Jul 18 2022 Jul 19 2022 Jul 28 2022 Jul 28 2022 Aug 26 |

00104 00104 35631 51303 - 00105 00105 - - - - - 35631 72824 73924 17610 20806 23075 - 00105 55065 - |

Initial Appointment Medicare Rebate Operative Laparoscopy Assistance at Operation Anaesthesia Subsequent Appointment Medicare Rebate Hospital Procedure Fee Hospital Day Accommodation Hospital Pharmacy Hospital Rapid Antigen Test Hospital Painkillers Medicare Rebate Tissue Pathology Pathology Collection/Handling Medicare Rebate Medicare Rebate Medicare Rebate Anaesthesia Refund Subsequent Appointment Pelvic Ultrasound Hospital Balance Refund |

-$300 +$76.80 -$2351.25 -$426.75 -$1820 -$180 +$38.60 -$2909 -$778 -$50 -$14.30 -$11 +$555.30 -$390 -$36 +$34.05 +$108.15 +$108.15 +$364 $0 $0 +$136 |

|

Total (AUD) |

-$7845.25 |

||

Table 3: Total Cost of Pelvic Operation in 2022

Preparation

A pre-operative appointment on Thursday 2nd June 2022 finalised and confirmed all details of the surgical procedure. Starting Tuesday 14th June 2022, the patient began clearing his bowels by fasting 3 days prior along with taking PicoPrep® laxative solution the night before operation.

Tuesday 14 June 2022

9:00am Started fasting from solid food. Low calorie consumption, clear liquids such as electrolytes, water and tea.

Wednesday 15 June 2022

9:00am Continued fasting with liquid consumption only.

Thursday 16 June 2022

9:00am Continued fasting with liquid consumption only.

6:00pm PicoPrep® laxative solution.

8:00pm Stopped all liquid consumption.

Friday 17 June 2022

5:00am Shower, comfortable clothes.

5:30am Paused medication (Testavan® gel).

6:00am Arrived at hospital. Checked-in.

6:30am COVID-19 Rapid Antigen Test (negative).

6:40am Admitted. Changed into surgical gown.

6:50am Vitals checked. Emptied bladder.

7:00am Pregnancy test (negative).

7:15am Pre-anaesthesia consultation.

7:25am Ultrasound of bladder to confirm emptiness.

7:30am Patient placed on operating table.

7:32am Anaesthesia administered.

7:35am Operation commenced.

Operation

A lead surgeon, assistant surgeon and anaesthetist were present along with nurses/technicians.

7:35am Patient placed in supine position. Lower abdomen draped and prepared for surgical incisions.

Figure 4: Supine vs. Trendelenburg

Figure 4: Supine vs. Trendelenburg

7:45am Hasson entry made by inserting a 10/12mm port at the umbilicus then three 5mm ports at the LLQ, RLQ and suprapubic abdominal regions.

Figure 5: Laparoscopic Port Incisions

Figure 5: Laparoscopic Port Incisions

Pneumoperitoneum is achieved at an intra-abdominal pressure of 12 to 15 mm Hg.

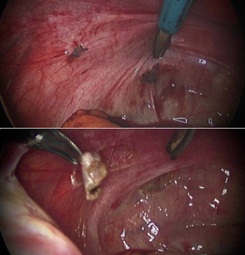

8:00am Systematic inspection of pelvis conducted. Uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes appeared normal. Appendix, liver and sub-diaphragmatic surfaces also normal. Uterus was propped up by the assistant with forceps through the suprapubic port (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Before Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy

Figure 6: Before Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy

8:10am Two gunpowder patches consistent with endometriosis identified on left pelvic side wall and in Pouch of Douglas (Figure 7). Both excised and sent for histopathology.

Figure 7: Endometriosis

Figure 7: Endometriosis

8:15am Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy commenced. Ovarian ligaments and infundibulo-pelvic ligaments cauterised and transected. Base of fallopian tubes with ovaries attached were separated from uterus.

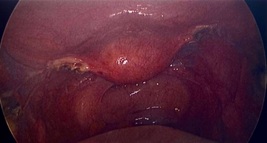

8:35am Tissue delivered with EndoCatchTM via umbilicus port. Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy complete (Figure 8).

Figure 8: After Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy

Figure 8: After Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy

8:40am Peritoneal lavaged and haemostasis secured.

8:45am Trocars removed. Incisions closed with polydioxanone and Vicryl RapideTM absorbable sutures. Marcaine with 1% adrenaline infiltrated into skin wounds. Lastly bandaged with waterproof Comfeel® dressings.

8:55am Anaesthesia stopped. Tissue sent to pathology.

Recovery

9:20am Patient went into shock upon waking up. Fentanyl was administered. Monitored in recovery unit.

10:30am Patient stabilised then moved to ward/room.

10:40am Rested further.

11:20am Awake and conscious. Reported pain from pressure in abdomen from insufflation. Wounds were normal.

1:00pm Lunch. Eating food as usual. Struggled sitting upright with abdominal pain and internal pressure. Nurse applied hot pack to ease internal pressure and assist in dissolving excess CO2. Effective after further resting.

2:30pm Up and walking. Changed clothes. Bathroom use normal. No significant pain, mild abdominal pressure.

3:00pm Post-operative surgeon visit. Debrief on findings and checked on wellbeing. All-clear to be discharged with after-care instructions and pain medication.

3:50pm Discharged home.

4:00pm Tapentadol IR 50mg (Palexia® IR) 4 day course dispensed from hospital pharmacy.

Post-Operative Instructions No heavy lifting or straining for 3-6 weeks. Leave waterproof wound dressings on for 7-10 days. Sutures will dissolve on their own. Shower as usual. Normal diet as tolerated starting with light meals and slowly building up. Natural laxatives such as psyllium husk to be used for assisting gentle bowel movements. Stay hydrated and empty bladder regularly to avoid over-distension. Time off physical work is 4 weeks while studies can be returned to within few days. Monitor for any abnormal bleeding. Continue Hormone Replacement Therapy as usual (Testavan® gel). Request GP blood tests to confirm healthy hormone levels and adjust if necessary. Follow up appointment with surgeon at 4-6 week mark.

Surgical Dressings Figure 9: Post-Operative Bandages

Figure 9: Post-Operative Bandages

Saturday 18 June 2022 Bed rest and sleeping at home.

Sunday 19 June 2022 Eating, drinking, resting at home.

Monday 20 June 2022 Mild walking, resting at home.

Tuesday 21 June 2022 Driving, walking, resting.

Pathology Results

Histopathology was reported on 21st June 2022. Macroscopic examination noted multiple small benign cysts having a maximum diameter of 6-8mm present on both ovaries and fallopian tubes. Microscopic examination of the ovaries and fallopian tubes appeared normal with no endometriosis being identified. A small benign paratubal serous cyst was identified on the right ovarian specimen. Both peritoneal biopsies had endometriosis, minor adhesions and chronic inflammation. No further concerns.

Initial Scars

Figure 10: Scars on 11 July 2022

Figure 10: Scars on 11 July 2022

Despite the blood soaked bandages after operation, the scars revealed to be very minimal in comparison (Figure 10).

Follow Up

A follow up appointment with the surgeon on Thursday 28th 2022 checked on the general condition and healing of the operative procedure. The removal of ovaries had succeeded in stopping the menstrual cycle. A quick pelvic ultrasound was conducted showing no abnormalities. Both surgeon and patient were satisfied with the outcome of the procedure. Hormone levels were to be monitored over the next few months.

New Blood Results

New hormone levels from 5th August 2022 are graphed (Figure 11).

Figure 11: New Estrogen & Testosterone Graph

Figure 11: New Estrogen & Testosterone Graph

Estrogen levels are consistently within range, while testosterone on 22nd August 2022 fell slightly below recommended laboratory minimum. The general practitioner advised patient to increase his daily Testavan® gel dosage to 69mg (3 actuations) to increase the levels. Hormone values from 13th October 2022 are since within range.

Conclusion

A successful bilteral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed without a uterine manipulator or urinary catherisation. The intended outcome was to cease the menstrual cycle and stablise reproductive hormonal levels typical for an adult male. The surgery was deemed medically necessary due to the patient’s prior heavy and painful menses which during the operation was found to be a cause of endometriosis. The treatment also resulted in gender affirming aspects for the transgender patient but was a secondary feature. Some improvements to the process are suggested such as fasting few days prior to surgery with- out the PicoPrep® laxative solution. Another suggestion is replacing the post-operative opioid painkillers to a medicinal cannabis oil such as AltheaTM CBD10:THC5 [31]. The patient reports medicinal cannabis to be a more effective pain relief with a milder comedown period [32]. Overall the experience has been a great success due to the patient's preparation and an experienced surgeon.

References

- Sandberg, A. Twijnstra, C. van Meir, H. Kok, N. van Geloven, K. Gludovacz, W. Kolkman, H. Nagel, L. Haans, K. Kapiteijn, and F. Jansen. “Immediate versus delayed removal of urinary catheter after laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomised controlled trial”. In: BJOG 126.6 (2018), pp. 804–813. doi: https://doi.org/10. 1111/1471- 0528.15580.

- Hilton. “Bladder drainage: a survey of practices among gynaecologists in the British Isles”. In: BJOG 95.11 (1988), pp. 1178–1189. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1471- 0528.1988.tb06797.x.

- Zmora, K. Madbouly, H. Tulchinsky, A. Hussein, and M. Khaikin. “Urinary Bladder Catheter Drainage Following Pelvic Surgery—Is It Necessary for That Long?” In: Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 53.3 (2010), pp. 321–326. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR. 06013e3181c7525c.

- S. Barnes. “Is It Better To Avoid Urethral Catheteriza- tion at Hysterectomy and Caesarean Section?” In: Aust & NZ J Obstet Gynae. 38.3 (2008), pp. 315–316. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479- 828X.1998. tb03074.x.

- Kenyon, J. Shields, T. Walsh, and K. Kho. “The Ba- sics of Uterine Manipulators: A Beginner’s Guide to this Essential Gynecologic Tool”. In: JMIG 26.7 (2019). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.506.

- Akdemir and T. Cirpan. “Iatrogenic uterine perfora- tion and bowel penetration using a Hohlmanipulator: A case report”. In: International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 5.5 (2014), pp. 271–273. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.10.005.

- Ketz and C. H. Nezhat. “Robot-Assisted Laparo- scopic Hysterectomy”. In: Springer Robotic Surgery (2021), pp. 1249–1257. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-3-030-53594-0_116.

- Tamburro, E. Nouhz, F. Calonaci, A. Wattiez, M. Ca- nis, and G. Mage. “Uterine manipulation in operative laparoscopy by suction disposable uterine device”. In: Gynaecology Surgery 8 (2011), pp. 343–346. doi: https: //doi.org/10.1007/s10397-010-0644-6.

- Freeman. “1256 Total Laparoscopic Hyterectomy Made Easier and Safer with Alan Utero-Vaginal Manip- ulator II-H”. In: JMIG 26.7 (2019). doi: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.279.

- U. Gisladottir, R. J. Drashko Nakikj, J. Panton, G. Brat, and N. Gehlenborg. “Effective Communication of Per- sonalized Risks and Patient Preferences During Surgi- cal Informed Consent Using Data Visualization: Qual- itative Semistructured Interview Study With Patients After Surgery”. In: JMIR Hum Factors 9.2 (2022). doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/29118.

- Tinelli, E. Cicinelli, A. Tinelli, S. Bettocchi, S. An- gioni, and P. Litta. “Laparoscopic treatment of early- stage endometrial cancer with and without uterine ma- nipulator: Our experience and review of literature”. In: Surgical Oncology 25.2 (2016), pp. 98–103. doi: https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2016.03.005.

- Kavallaris, N. Chalvatzas, K. Kelling, M. K. Bohlmann, K. Diedrich, and A. Hornemann. “Total laparoscopic hysterectomy without uterine manipula- tor: description of a new technique and its outcome”. In: Archives of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 283 (2011), pp. 1053–1057. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00404-010-1494-1.

- Zygouris, N. Chalvatzas, A. Gkoutzioulis, G. Anas- tasiou, and A. Kavallaris. “Total laparoscopic hys- terectomy without uterine manipulator. A retrospective study of 1023 cases”. In: European Journal of Obstet- rics & Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology 253 (2020), pp. 254–258. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ejogrb.2020.08.035.

- Mitsopoulou, A. Papadopoulos, E. Papadopoulou- Skordou, A.-A. Papathanasiou, C. Papapetrou, and N. Vlahos. “Gender dysphoria in the field of obstetrics and gynecology”. In: Med 2.5 (2021), pp. 475–481. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.04.024.

- Kershaw and S. Jha. “Adolescent gynaecology”. In: Obstet Gynae & Reprod Med 31.9 (2021), pp. 261–267. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogrm.2021.06.009.

- Pandis, L. Michala, S. Creighton, and A. Cutner. “Minimal access surgery in adolescent gynaecology”. In: BJOG 116.2 (2009), pp. 214–219. doi: http://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01995.x.

- Leithner, E. Assem-Hilger, A. Naderer, W. Umek, and M. Springer-Kremser. “Physical, sexual, and psycho- logical violence in a gynaecological-psychosomatic out- patient sample: prevalence and implications for mental health”. In: Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 144.2 (2009), pp. 168–172. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.ejogrb.2009.03.003.

- Mason and Z. Lodrick. “Psychological consequences of sexual assault”. In: Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gy- naecol. 27.1 (2013), pp. 27–37. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.015.

- B. Wijma, B. Schei, K. Swahnberg, M. Hilden, K. Of- ferdal, U. Pikarinen, K. Sidenius, T. Steingrimsdottir, H. Stoum, and E. Halmesmaki. “Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in patients visiting gynaecology clin- ics: a Nordic cross-sectional study”. In: Lancet. 361.9375 (2003), pp. 2107–2113. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(03)13719-1.

- Oates and D. Gath. “Psychological aspects of gynae- cological surgery”. In: Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 3.4 (1989), pp. 729–749. doi: https://doi.org/10. 1016/s0950-3552(89)80062-8.

- Cho, J.-W. Roh, J. Park, K. Jeong, T.-H. Kim, Y. S. Kim, Y.-S. Kwon, C.-H. Cho, S. H. Park, and S. H. Kim. “Safety and Effectiveness of Dienogest (Visanne®) for Treatment of Endometriosis: A Large Prospective Co- hort Study”. In: Reprod Sci. 27.3 (2020), pp. 905–915. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-019-00094-5.

- Australian Clinical Labs. 2022. url: https://www.clinicallabs.com.au/

- Southern IML Pathology. 2022. url: https://www.southernpath.com.au/

- Laverty Pathology. 2022. url: https://www.laverty.com.au/

- Moore, A. Wisniewski, and A. Dobs. “Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual People: A Review of Treat- ment Regimens, Outcomes, and Adverse Effects”. In: The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 88.8 (2003), pp. 3467–3473. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1210/jc.2002- 021967.

- P. Crum. “Intercepting pelvic cancer in the distal fal- lopian tube: Theories and realities”. In: Molecular On- cology 3.2 (2009), pp. 165–170. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.01.004.

- R. Fountain and L. J. Havrilesky. “Promoting Same-Day Discharge for Gynecologic Oncology Patients in Minimally Invasive Hysterectomy”. In: JMIG 24.6 (2017), pp. 932–939. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jmig.2017.05.005.

- Li, H. Saravelos, M. Richmond, and I. Cooke. “Com- plications of laparoscopic pelvic surgery: recognition, management and prevention”. In: Human Reproduction Update 3.5 (1997), pp. 505–515. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/humupd/3.5.505.

- Willis, L. Reynolds, and T. Rudge. Understanding the Australian Health Care System. Elsevier Australia & Sons, 4th Edition, 2020, pp. 17–52. isbn: 978-0-7295- 4328-6.

- Australian Medicare Benefit Schedule. 2022. url: http: //www.mbsonline.gov.au/.

- Althea - Medicinal Cannabis. 2022. url: https://althea.life/medicinal-cannabis-the-basics/.

- Stewart and Y. Fong. “Perioperative Cannabis as a Potential Solution for Reducing Opioid and Benzo- diazepine Dependence”. In: JAMA Surg. 156.2 (2021), pp. 181–190. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/ jamasurg.2020.5545.

Appendix A - Consent Form (Public Hospital)

Appendix B - Consent Form (Private Hospital)

Citation: Tutoveanu A, Choi S (2023) Success of Medically Necessary Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy without Uterine Manipulator or Urinary Catheter. J Reprod Med Gynecol Obstet 8: 126.

Copyright: © 2023 Anton Tutoveanu, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.