Teaching Population Health in the Digital Age: Community-Oriented Primary Care 2.0

*Corresponding Author(s):

Winston R LiawFairfax Family Medicine Residency Program, Virginia Commonwealth University, Virginia, United States

Tel:7037867997,

Email:winstonrliaw@gmail.com

Abstract

Providers and educators lack the tools and models necessary to address community problems. We describe an online curriculum intended to teach learners how to adapt established Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC) principles for an age of ready access to clinical and population data and geospatial technology. Via our approach, users gain practical knowledge that allows them to operationalize the fundamental steps of COPC: community definition, identification of health needs, intervention development, and program monitoring. These skills are essential in a new era of population health management and in encouraging primary care providers to partner with their communities.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In 2001, a nurse named Jeanie Schmidt discovered that children in her Virginia community were not registering for school because their families could not afford a visit needed to complete the state-required entrance physical exam and that the safety net clinics had waiting lists. Concerned about this gap, she reached out to community partners, and together, they created a free clinic. Today, that clinic serves as an educational home for family medicine residents, nursing students, and nurse practitioner students. However, like many teaching sites, it struggles to pass along Jeanie’s ability to rally communities to the next generation of primary care providers.

Given rising health care costs and care fragmentation, policy makers have renewed their focus on population health [1]. New models of care such as patient centered medical homes and accountable care organizations reward organizations that implement systemic changes within practices and communities. Unfortunately, the scope and adoption of these payment modalities are too limited to trigger widespread primary care delivery transformation.

Recent calls by the US Institute of Medicine (IOM) to better integrate public health and primary care suggest that the time may have arrived to finally realize the ambitions of the Folsom Report [2,3]. Jointly organized by the National Health Council and the American Public Health Association, the Folsom Report was released in 1967 and aimed to address the accessibility and availability of community health services [4]. Its authors introduced the concept of a community of solution to address community-level problem sheds, which, like watersheds, ignore political and jurisdictional boundaries and require the coordination of relevant stakeholders.

Providing examples of communities of solution and discussing the importance of addressing social determinants of health may stimulate the interest of trainees. But getting the next generation of primary care providers and public health officials to embrace population health and team based care, will require experience and a roadmap. Another concept well ahead of its time - Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC) - offers a practical approach by which primary care providers can realize Folsom’s charge to serve as agents of community health improvement.

Building on fifty years of multinational experiences, including success stories in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Europe and Central America, (Table 1) [5] COPC is defined as a “continuous process by which primary health care is provided to a defined community on the basis of its assessed health needs by the planned integration of public health and primary care” [6].

| Folsom Report Recommendations [3] | COPC Principles | COPC 2.0 |

| “Organization and delivery of community health services community of solution by relevant administrative area, not by political jurisdictions”. | Engagement of community organizations and partners that can assist with addressing identified health needs, regardless of political jurisdictions. | Use of search engines such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Innovations Exchange to determine what others are doing to address similar health needs [8]. |

| “Provision of high-quality comprehensive personal health services to all people in each community”. | Focus on caring for all persons living within a defined community rather than only the patients coming to the clinic. | Use of online Census data to determine the number of people within a community and online Geographic Information System (GIS) tools in conjunction with electronic health information to determine the number and location of people the practice already sees. |

| “Every individual should have a personal physician who is the central point for integration and community of all medical and related services to the patient”. | ||

| “Prospective planning and management of comprehensive environmental health services, includes water, air, food, hygienic housing, activity, and recreation”. | Encouragement of practices to develop interventions directed at social determinants of health. | Use of online GIS databases such as the United States Department of Agriculture Food Atlas to assess the state of social determinants of health in the community [9]. |

| “Education for health: The community has a responsibility for developing an organized and continuing education concerning health resources for its residents; each individual has a personal responsibility for making full use of available health resources”. | Encouragement of community engagement in planning, implementing, and monitoring interventions. | Identification of existing community resources using the AHRQ Innovations Exchange and nearby health center program grantees using the Uniform Data System Mapper in an effort to identify a broader coalition of potential partners [10]. |

| “Voluntary citizen participation: A central factor in the growth and development of personal and community health has been the participation of individuals and voluntary associations through dedicated leadership, financial support, and personal service”. |

Table 1: How Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC) can address the Folsom report recommendations.

There are four process steps embedded within COPC (Figure 1),

1) Defining the community of interest

2) Identifying the health need

3) Developing and implementing interventions

4) Conducting an ongoing evaluation [7]. Figure 1: Community-oriented primary care process steps.

Figure 1: Community-oriented primary care process steps.

Several principles guide COPC projects. First, COPC interventions focus on all patients within a defined community rather than just the patients coming to the clinic. Second, COPC interventions target communities rather than individual patients. For instance, a COPC project may focus on increasing the walkability of a community rather than identifying clinic patients with uncontrolled diabetes. Finally, COPC is rooted in the belief that the community should be involved at every step [5].

Once the subject of books and IOM reports, COPC is rarely employed in modern US primary care due to a lack of financial incentives for practices to focus on population health or the tools for its implementation [11]. However, given the US’s commitment to the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving population health, and reducing health care costs, the principles of COPC may resonate today even more, just as they resonated with the forefathers/mothers of primary care. Sidney and Emily Kark, who coined the phrase COPC, vigorously studied the area surrounding the Pholela Health Center in South Africa and developed interventions, in conjunction with community members that addressed social determinants [12]. Having trained with the Karks, H Jack Geiger helped birth the community health center movement in the US, using COPC as his guiding framework [13].

While some changes in the health care landscape have increased the urgency of disseminating COPC, another movement in health care has made COPC easier to implement. The adoption of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) has expanded the amount of available health information, while the growth of online mapping resources has allowed primary care providers to make those data more customizable and actionable [14]. Online tools such as Health Land scape’s Health Center Mapping Tool, were constructed to integrate clinical and population data and to allow users to better understand their practice service area and the social determinants that influence their patient’s health. On a macro level, the Uniform Data System (UDS) Mapper allows federal planners and health center program grantees to visualize the communities served by the nation’s primary care safety net clinics. Providers seeking more community data that might shape their practice of COPC also now have access to online resources, including the County Health Rankings which ranks counties using a variety of health measurements and American Fact Finder which publishes census tract level demography data from the US Census [7,15-17] In short, processes such as mapping the location of patients that once took the Karks and Geiger months to complete can now be performed in a matter of hours [18,19].

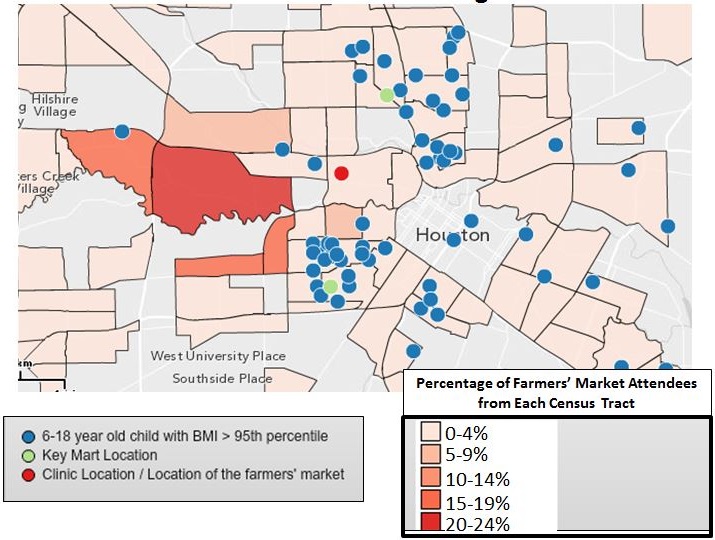

The push to integrate primary care and public health has led to initiatives to integrate primary care and public health data. The IOM released a report in 2014 listing data elements recommended for inclusion into EHRs because they capture social determinants of health [20]. The manifestation of this ideal is a world where clinicians have access to not only biometric vital signs but also community vital signs, providing a measure of the resources available in the patient’s community. But even with this wealth of tools, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledges that we lack a playbook for achieving integration [21]. To take this playbook to learners, the National Association of Community Health Centers, the Robert Graham Center, and Virginia Commonwealth University have created a curriculum that reintroduces COPC principles. We developed four modules and a case study that demonstrate how to harness the potential of COPC while offering concrete ways of accessing community data [22]. In this curriculum, educators can reference diverse resources, including instructions on how to geocode data and a bibliography of seminal articles. The case study allows learners to follow one community health center’s fictional experience implementing COPC (Figure 2). In completing this exercise, learners upload practice data, generate and interpret maps, and discuss the implications of the project from the lens of community members. Figure 2: Except from the community-oriented primary care case study - percentage of farmer's market attendees from each census tract and locations of overweight children.

Figure 2: Except from the community-oriented primary care case study - percentage of farmer's market attendees from each census tract and locations of overweight children.

This curriculum is being piloted at US family medicine residencies, but more resources are needed to document the impact of the curriculum and to disseminate these principles nationwide. Going through the steps of the COPC process forces providers to become aware of the problem sheds facing their patients and communities and opens the door to community engagement, partnership, and the pursuit of communities of solution. Returning these principles to a central role in family medicine education will galvanize learners to move outside of the clinic, increase their likelihood of integrating primary care and public health, and foster the development of future Jeanie Schmidts.

REFERENCES

- Landon BE, Grumbach K, Wallace PJ (2012) Integrating public health and primary care systems: potential strategies from an IOM report. JAMA 308: 461-462.

- Institute of Medicine (2012) Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health, Institute of Medicine, USA.

- Folsom Group (2012) Communities of solution: the Folsom Report revisited. Ann Fam Med 10: 250-260.

- Roberts DW (1966) Health is a community affair. Preview of the final report of the National Commission on Community Health Services. JAMA 196: 332-333.

- Gofin J, Gofin R (2011) Essentials of global community health. Jones and Bartlett Learning, MA, USA.

- Mullan F, Epstein L (2002) Community-oriented primary care: new relevance in a changing world. Am J Public Health 92: 1748-1755.

- Institute of Medicine (1984) Community oriented primary care: A practical assessment. Institute of Medicine (US) Division of Health Care Services, National Academies Press, Washington (DC), USA.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014) AHRQ Innovations Exchange, USA.

- United States Department of Agriculture (2014) USDA Food Atlas, USA.

- http://www.udsmapper.org/index.cfm

- Connor E, Mullan F (1983) Community oriented primary care: New directions for health services delivery. Institute of Medicine (US) Division of Health Care Services, National Academies Press, Washington (DC), USA.

- Longlett SK, Kruse JE, Wesley RM (2001) Community-oriented primary care: historical perspective. J Am Board Fam Pract 14: 54-63.

- Geiger HJ (1993) Community-oriented primary care: the legacy of Sidney Kark. Am J Public Health 83: 946-947.

- Hsiao CJ, Hing E, Socey TC, Cai B (2011) Electronic health record systems and intent to apply for meaningful use incentives among office-based physician practices: United States, 2001-2011. NCHS Data Brief 79: 1-8.

- http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/

- http://www.healthlandscape.org/

- http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

- Bazemore A, Phillips RL, Miyoshi T (2010) Harnessing Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to enable community-oriented primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 23: 22-31.

- Mullan F, Phillips RL Jr, Kinman EL (2004) Geographic retrofitting: a method of community definition in community-oriented primary care practices. Fam Med 36: 440-446.

- Institute of Medicine (2014) Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains in Electronic Health Records: Phase 1. National Academies Press, Washington (DC), USA.

- https://practicalplaybook.org/

- USA (2014) COPC curriculum for educational health centers, Robert Graham Center, USA.

Citation: Liaw WR, Bazemore AW, Rankin J (2015) Teaching Population Health in the Digital Age: Community-Oriented Primary Care 2.0. J Community Med Public Health Care 2: 003.

Copyright: © 2015 Winston R Liaw, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.