Tetradic Model of the Human Psyche Incorporating Active versus Passive Mindfulness with Psychotherapeutic Applications

*Corresponding Author(s):

Andrew J HedeHede Research Consulting, Sydney, Australia

Tel:+61 416168281,

Email:ajjhede@gmail.com

Abstract

A new conceptual model of the human psyche is proposed comprizing four structural components and two operational forms of mindfulness. The first component of the psyche is the ‘Sub-selves’ theorized to be the source of one’s constant ‘mindchatter’ and the cause of much of the mental disturbance encountered in psychotherapy especially in depression. The second component is the ‘Managing-ego’ which is responsible for everyday interaction with other people and with the outside world. The third component is the ‘Inner-observer’ which is posited as one’s ‘true self’ able to passively observe one’s mental processes without any active intervention. The final component is the ‘Unconscious’ which is acknowledged but is not further explored. This tetradic model also integrates mindfulness into the dynamics of the psyche. Specifically, it postulates that ‘active mindfulness’ operates in conjunction with the Managing-ego whereas ‘passive mindfulness’ engages only when the Inner-observer is neutrally involved as a watcher ‘above mind’. Two recognized therapeutic mechanisms are integrated into the model. One is ‘decentering’ whereby the Managing-ego uses active mindfulness to separate oneself from the content of one’s own thoughts. The other is ‘disidentification’ which can result from the passive mindfulness of one’s Inner-observer enhanced by stillness meditation practice. The psychotherapeutic technique of Voice Dialogue is reviewed as an effective tool for applying the model. Three diverse composite case examples are presented which demonstrate how the proposed tetradic model can be applied in psychotherapeutic practice and can also be tested in future empirical research.

Keywords

Active versus passive mindfulness; Practical applications; Tetradic model of the psyche; Therapeutic mechanisms; Voice Dialogue

Introduction

One of the earliest recorded insights about the human psyche originated more than two millennia ago with the Buddhist concept of ‘monkey mind’ [1,2]. This metaphor-as-theory asserts that the human mind is forever busy, constantly darting from topic to topic sometimes generating confusion if not chaos within one’s psyche [3,4]. A related concept is that of ‘mindchatter’, the universal phenomenon of the human mind barraged by non-stop inner babble which is experienced as multiple internal voices [4,5]. These two ancient concepts are highly relevant for understanding the nature of the psyche today, that is, as it is encountered by each of us personally every day and as presented by troubled individuals in psychotherapy and in other therapeutic disciplines. An example of the therapeutic application of ‘monkey mind’ is the work of Eliuk and Chorney [6] with tertiary students experiencing stress because they were unable to calm their mind or control their thoughts. This research concluded that the ‘monkey mind’ can be controlled via mindfulness training as is explored in this article.

Arguably, the ancient psychological theory and practice that has gained most acceptance in contemporary Western psychotherapy is ‘mindfulness’ [7-12]. Confirmation of the spread of mindfulness research is provided by a website which has collated every relevant scholarly article published since 1980, totalling 9,545 by end of 2022 (see American Mindfulness Research Association Library [goamra.org]). Further confirmation comes from a recent bibliometric analysis that reported identifying more than 16,000 publications mentioning ‘mindfulness’ between 1966 and 2021 [13]. Importantly, however, Phang and Oei [14] pointed out that mindfulness is only one of eight Buddhist contemplative practices covered by the term ‘meta-mindfulness’.

It is widely acknowledged that the concept and practice of mindfulness was introduced to the Western world by Jon Kabat-Zinn who in 1979 established the Mindfulness Centre at the University of Massachusetts, USA. The initial focus of this centre was chronic pain [8] and also stress reduction [15-17]. Later, Kabat-Zinn’s 8-week training program in mindfulness spread to other countries including those implementing cognitive behavior therapy [18-23]. These two major applications of mindfulness (viz., MBSR and MBCT) were thoroughly reviewed in Baer’s [24] guide for clinicians. A meta-analysis by Goldberg et al., [25] of 142 separate study samples comprizing 12,005 participants found that mindfulness-based treatments of psychiatric disorders were more effective than nil or minimal treatments. Further, a comprehensive meta-analysis concluded that mindfulness-based interventions can be effective in treating serious mental disorders such as primary psychosis [26]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of meditation and mindfulness-based interventions in prisons and in Covid-19 lockdowns, confirmed their efficacy as remedies for maladaptive psychological behaviors [27]. However, a recent empirical study of the efficacy of brief induction into mindfulness meditation suggested that more extensive training may be needed to ensure beneficial results re psychological health [28]. The importance of mindfulness as a contemporary psychological theory raises the question of how it can be explained in terms of existing models of the human psyche.

Models Of The Human Psyche

Conceptual models have long been integral to theory development in psychology and related disciplines including psychotherapy and counselling [29]. The most widely accepted model of the psyche is Freud’s tripartite model of personality comprizing the Id, Ego and Superego [30,31]. Another historically relevant model is that by Jung addressing the ‘structure and dynamics of the psyche’ [32]. Other models have been proposed over the years [33,34], but Freud’s and Jung’s traditional models of the psyche still predominate. While these previous models of the psyche are clearly different, they all employ underlying constructs that are analogous to real-life human characteristics and abilities such as thinking, feeling, values and behavior patterns that can be inferred from observable behavior. However, these models do not feature prominently in the current mindfulness literature which is so influential in guiding contemporary clinical psychology and psychotherapeutic practice. The new model proposed here aims to explain the psyche in terms of its four structural components as well as its two operational forms of mindfulness.

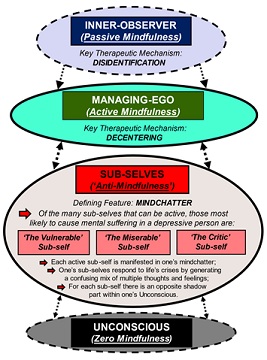

Let’s now consider the four structural components of the proposed model which draws on the models previously advanced by Miller et al. [35], Deikman [36] and Hede [37-39] (see later discussion). Figure 1 depicts a new tetradic model of the human psyche comprizing four structural components: 1) the Sub-selves, 2) the Unconscious, 3) the Managing-ego, and 4) the Inner-observer

Figure 1: Tetradic model of the human psyche depicting how the four structural components interact with the active versus passive forms of mindfulness (each of which has a specified therapeutic mechanism). (NB. Depression is used as an example).

Figure 1: Tetradic model of the human psyche depicting how the four structural components interact with the active versus passive forms of mindfulness (each of which has a specified therapeutic mechanism). (NB. Depression is used as an example).

- Sub-selves

The most active level of the human psyche consists of the ‘Sub-selves’ (Figure 1). This group of self-components is responsible for one’s ever-present mindchatter experienced as myriad thoughts/voices inside one’s head [4]. It’s rather like having several radio stations tuned in simultaneously – you can’t focus on a single thought (as voiced internally) without other thoughts breaking into your consciousness. This internal behavior is typical for every mentally healthy individual but it can be problematic for those who are mentally troubled. It is important here to distinguish the psychologically normal voices of mindchatter from the distressing voices or ‘auditory verbal hallucinations’ that can cause serious mental disturbance [40]. Amid the babble of one’s ‘monkey mind’ [1,4] a depressed individual will typically experience repeated conflicting commands by their currently active Sub-selves (e.g., ‘The Vulnerable’, ‘The Miserable’ and ‘The Critic’ – see Figure 1). The mental voices making up a depressive individual’s mindchatter might include thoughts/assertions such as: ‘Life’s so unfair’, ‘It’s all hopeless’, ‘You’re a total loser!’, ‘Just give up!’, etc. Such relentless negative inner commentary about one’s thoughts and feelings can drown out any support that might be provided by a troubled person’s positive Sub-selves (e.g., ‘The Resilient’ and ‘The Striving’) [41,42].

Of the many Sub-selves comprizing this level of the psyche, only four or five of them will be active (i.e., internally vocalized) at any one time [43]. As well as giving rise to such mental mindchatter, our Sub-selves react emotionally to life’s inevitable stresses and crises. It is this mix of conflicting thoughts and feelings that can cause considerable distress for an already disturbed individual (Figure 1) [41,43-45]. A major challenge in psychotherapeutic interventions, however, is that many clients may not be able to access mindfulness as a technique to calm the chaos of their mind because of ‘anti-mindfulness’ (see later). The final feature of this level of the psyche is that the Sub-selves are each mirrored by a Jungian-type shadow [46,47] which is opposite to them in nature and operation but is unconscious. Consequently, the shadow is unknown to the individual thereby rendering it beyond the scope of the present model and its psychotherapeutic applications (Figure 1).

- Unconscious

In the proposed tetradic model of the psyche, the base level of the four structural components is the Unconscious (Figure 1). This construct can be traced back to the early years of Buddhist psychology more than 2,000 years ago [12,48]. Over many centuries it has evolved into the modern Western construct largely due to the theorizing of Freud [31] and later Jung [32] [49]. For example, Freud’s 1915 revolutionary book argued that all humans have both a conscious and an unconscious mind [31]. With his medical colleague, Janet, Freud later challenged the early 20th Century view that the serious ailments that then eluded medical understanding were not evidence of demons but rather were derived from human processes within the patient’s own psyche [50]. Freud’s construct of the Unconscious was central to psychoanalysis, his primary therapeutic technique [51]. However, for modern psychotherapeutic applications, a therapist does not need to delve into the Unconscious beyond being aware that it is present within the tetradic human psyche (Figure 1). A psychotherapist can use the technique of Voice Dialogue [43-45,52,53] to facilitate their clients in expressing (vocally) their Sub-selves and thereby unravelling the mindchatter that underlies much of their mental disturbance.

- Managing-ego

The next structural component in the tetradic model of the human psyche is the ‘Managing-ego’ which is comparable with but not identical to several published models including Freud’s [31] concept of the Ego as well as Stone and Stone’s [43,45] construct of the Aware Ego (Figure 1). This core component of the Managing-ego is postulated to operate as a regulator charged with overseeing and controlling our interactions with others and also with the outside world while simultaneously striving to keep our Sub-selves in check [39]. Thus, our Managing-ego defines who we are as perceived by our other Sub-selves and also by those around us. Its key function is to monitor and manage one’s currently active Sub-selves. An individual is thereby able to objectify their own Sub-selves and so detach from their constant mindchatter as being mere background babble which can be ignored. With the guidance of a psychotherapist, an individual can learn to treat their mindchatter as mental static rather than as authoritative commands that must be obeyed [39]. A psychotherapist can also help the individual to experience and thus understand their active Sub-selves first-hand by vocalizing each in turn while relying on their Managing-ego to monitor with detachment [45,52,53].

- Inner-observer

The most important but also the most overlooked component of the human psyche is here termed the ‘Inner-observer’ (Figure 1). This construct denotes one’s higher self (sometimes labelled ‘true self’) which is generally ignored in the scholarly literature but is acknowledged in several published models [36,37]. It is somewhat comparable to the construct of ‘self as context’ or observing self in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in that both allude to the Eastern notion of a transcendent self [54]. The proposed Inner-observer entity functions only by detachedly watching the mental activity within one’s other selves (viz., one’s Managing-ego and Sub-selves; Figure 1). However, it can do so only when it is in a state of mental ‘stillness’ and neutrality (i.e., passive mindfulness – see next section) which operates above the busyness of one’s mind especially one’s mindchatter [4,5]. Most people are unable to experience their own Inner-observer as being separate from the endless mindchatter of their dominant Sub-selves which they erroneously identify as being their only self which they must obey [39].

Forms of Mindfulness in the Tetradic Psyche

In addition to the four structural components outlined above, the proposed tetradic model of the psyche identifies two forms of mindfulness as the operating modes of one’s various selves (Figure 1). Although the scholarly literature generally regards mindfulness as a unitary construct which is equivalent to the present concept of active mindfulness, a binary model of mindfulness has been proposed distinguishing between an active and a passive form of mindfulness [39]. The primary form, ‘active mindfulness’, can be defined [55] as: ‘non-judgemental and non-reactive awareness that arises through paying attention on purpose and openheartedly in the present moment’. This form of mindfulness has been promoted widely in Western medicine and psychotherapy over recent decades by Kabat-Zinn [9] and his colleagues (specifically, in stress reduction and also cognitive behavior therapy as outlined above). However, this psychotherapeutic approach is primarily based on the active mental process of focused attention and open monitoring which is different from the neutral observation during stillness meditation where the individual achieves an ‘above mind’ state of being fully aware but completely detached and passive [39]. Thus, the present proposed model incorporates both active versus passive mindfulness in order to fully account for the complexities of human behavior (Figure 1). It is important to acknowledge that there is an extensive research literature on the underlying behavioral factors which determine the efficacy of mindfulness [56,57]. However, these conceptual models as verified in empirical questionnaires, all deal with what Hede [39] would consider to be the active rather than the passive form of mindfulness.

Examining the four components of the tetradic model, it is here postulated that the Unconscious is incapable of any form of mindfulness (i.e., ‘zero mindfulness’ – Figure 1). By definition, the Unconscious operates outside one’s conscious mind where it is able to wreak psychological havoc [49]. Nor does the Sub-selves level of the human psyche allow any mindfulness but rather involves what can be labelled as ‘anti-mindfulness’ (Figure 1). Although not strictly a theoretical construct (as compared with active and passive mindfulness), anti-mindfulness is proffered as a mental activity of the Sub-selves which creates a total block to any form of mindfulness at this level due to their unceasing and all-consuming mindchatter (see above). This contrasts with active mindfulness which is theorized to entail the Managing-ego actively focussing attention on whatever one is experiencing here and now without any mental commentary (Figure 1) [39]. In contrast to this active surveying by the Managing-ego, passive mindfulness is here defined as a state whereby one’s Inner-observer engages in totally neutral watching of one’s own mental activity (Figure 1) [37]. This completely impartial state, sometimes called ‘no mind’ or ‘emptiness’ [58], can be achieved only via the inner stillness that is accessible using thought-free meditation.

Comparison of Proposed Tetradic Model with Relevant Previous Models

The proposed model draws on some constructs in previous models [35,36] and further develops those proposed previously by the author [37,39]. Table 1 presents a comparison of the currently proposed three main structural components and the two operating forms of mindfulness with related but non-identical constructs in relevant previous models. First, Miller et al. [35] distinguish between the observation and experiencing functions in Freud’s construct of the Ego. While this Freudian model does not include mindfulness, the observation and experiencing functions are performed by the Managing-ego and the Sub-selves in the proposed model, respectively (Table 1). The second comparison model is that of Deikman [36] which includes three constructs which are similar to the three structural components proposed here (Table 1). Importantly, Deikman’s construct of the ‘observing self’ as the ‘subject of consciousness’ is comparable to the present Inner-observer though the latter construct differs operationally in its use of passive mindfulness (see previous section). Hede’s [37] model attempts to explain the dynamics of mindfulness as it operates when individuals experience emotional reactions and stress. It distinguishes between the executive function of the ‘Meta-Self’ and the observation function of the ‘Supra-Self’. These two constructs have been further developed in the proposed model of the psyche (Table 1).

|

Miller et al. [35] |

Deikman [36] |

Hede [37] |

Proposed Tetradic Model |

|

|

Observing-Self [Subject of Consciousness] |

Supra-Self [Inner-Observer] |

Inner-Observer [Passive Mindfulness] |

|

Observing Ego [Integrative self-observation function] |

Functional Self [Part of Object Self] |

Meta-Self [Managing Ego] |

Managing-Ego [Active Mindfulness] |

|

Experiencing Ego [Cognition, affect & perception] |

Emotional Self & Thinking Self [Parts of object self ] |

Sub-Selves [Thoughts, feelings & sensations] |

Sub-Selves [Thoughts, feelings & sensations] |

Table 1: Comparison of the proposed tetradic model with constructs in relevant previous models.

Therapeutic Mechanisms in Tetradic Model

There has been considerable published theory and research on the mechanisms that underly the therapeutic effects of mindfulness in treating mental health conditions such as stress, anxiety and depression [42,59,60]. The proposed tetradic model identifies the specific mechanisms that determine the therapeutic efficacy of the two forms of mindfulness distinguished here (viz., active versus passive mindfulness; Figure 1). In the case of the Managing-ego, the main therapeutic mechanism is ‘decentering’, the process by which an individual uses active mindfulness to detach from the content of their own thoughts [39,61,62]. This construct is linked to that of ‘metacognition’ which has been found to be relevant in clinical practice [63]. In particular, the Managing-ego can objectify one’s Sub-selves thereby neutralizing the negative effects of their mindchatter [37].

The other key therapeutic mechanism specified in the present model is ‘disidentification’ (Aronson et al., see the Inner-observer self-component in Figure 1) [64]. Whereas active mindfulness can intervene directly in one’s mental processes, we have seen above that passive mindfulness plays a strictly observational role that is completely neutral. The rationale for disidentification is that if an individual can neutrally observe the activity of their own mind, then their mind must be an object composed of their mind’s thoughts (i.e., an ‘other-than-true-self’). By logic, one’s Inner-observer must exist ‘above mind’. Descartes might well have elaborated on his famous aphorism ‘I think, therefore I am’ by adding: ‘…therefore, I am not my thoughts, and thus my true being must exist separately from my thoughts’ [39]. Consequently, the daily practice of stillness meditation can help people grasp this insight by which they can begin to identify their own existence with their true self rather than with their dominant Sub-selves [39,64]. Importantly, the thoughts that pop-up in our mind, including self-destructive thoughts, are not ours unless we specifically allow them to become our own.

Dynamics within the Psyche

As well as positing four structural components and two forms of mindfulness, the present tetradic model attempts to account for the clinically important interactions within the psyche as depicted by the arrows between the various elements in Figure 1. The most frequent intra-psychic interaction is that between the Sub-selves and the Managing-ego which is the focus of the psychotherapeutic technique of Voice Dialogue. This technique was originally developed by clinical psychologists, Stone and Stone, as a method of face-to-face therapy based on their theory ‘Psychology of Selves’ [43,45] and has been adapted here for the main practical application of the proposed tetradic model.

In essence, Voice Dialogue is a clinical intervention in which a psychotherapist invites a client to experience their own complex mental processes by allowing their currently dominant Sub-selves (such as, for example: The Vulnerable, The Miserable, The Critic – Figure 1) to express themselves sequentially by vocalizing aloud [45,52,53]. It is important to emphasize that the ‘voices’ a person accesses via Voice Dialogue are not the physical/sonic voices of psychosis [40,65,66], but rather the everyday experience of thoughts within the normal human mind, especially, one’s ‘mindchatter’ [4].

This role-play process is further facilitated by the client’s guided use of the identificatory assertion: “I am [client inserts agreed label for their specific sub-self] and I am experiencing the following thoughts here and now….” Surprisingly, only simple instructions and a little practice of Voice Dialogue is needed by most clients for them to experientially ‘become’ the Sub-self they are voicing [53]. Most importantly, in the tetradic model the client is instructed to monitor their own ‘voices’ using active mindfulness via their Managing-ego [39,45]. After each role-play of a Sub-self, the client moves physically back to the ‘Managing-ego’ position/chair and is then invited to debrief by sharing the insights they have gained by detachedly witnessing their own role-play [43,45,53].

Unlike psychotherapeutic interventions involving deep probing of the unconscious, Voice Dialogue has proven to be a powerful but safe technique that enables a client to experience their own mental processes and, thereby, to separate from and clarify the confusion and chaos caused by their multiple inner voices expressing the mindchatter of their Sub-selves. Coupled with the key therapeutic mindfulness mechanisms outlined above (viz., decentering and disidentification), clients can learn to use the simple but effective intervention of Voice Dialogue to understand the essential dynamics of their own psyche. It is this combination of understanding their psyche while practising the skills of both active and passive mindfulness that clients can shift the locus of control of their psyche from their Sub-selves to their Managing-ego under the watchful eye of their Inner-observer [39].

Composite Case Examples of Psychotherapeutic Applications Using the Proposed Model

The following three composite case examples which demonstrate applications of the model, were sourced from multiple psychotherapeutic interventions undertaken during the 18 years while the author was a Registered Psychologist in Australia. The relevant confidential and anonymous counselling sessions were conducted in accordance with established professional standards. Identifying personal details are altered here in order to ensure subject anonymity.

- Case 1: Sun Li (aged 29)

Applying the proposed tetradic model of the human psyche in psychotherapeutic intervention, an illustrative composite example is that of Sun Li, a system installer for a high-tech communications company. Sun Li had long aspired to being promoted as a technical supervisor with responsibility over eight installers, but felt he was being treated unfairly by not receiving the same level of technical support as his co-workers. In his five years with the company, Sun Li had often been praised for his technical competence and work ethic, but he had increasingly become embroiled in interpersonal conflict with other staff and even customers. Sun Li presented for psychotherapy having been referred compulsorily by his supervisor for his perceived anger problem.

Sun Li told his psychotherapist that he felt compelled to defend himself assertively, otherwise “everyone will keep treating me as a weakling”. His therapist outlined the basics of cognitive therapy and the dynamics of one’s mindful psyche (Figure 1). Sun Li expressed surprise that the voices in his head were not his own ‘must-obey’ commands. When someone offended him, his therapist explained, his anger reaction arose from one or more ‘Sub-selves’ in his psyche (most likely, ‘The Vulnerable’ sub-self). Sun Li was relieved to learn about ‘decentering’ whereby his Managing-ego is able to use active mindfulness to monitor his responses to any ill-treatment by others and then to detach himself from the content of the reactive thoughts his Sub-selves might generate [61].

- Case 2: Natasha (aged 52)

A more complex composite example is that of Natasha, an executive in a large accounting firm. Natasha had been highly successful in her ten years employment progressing to client relations director, but over the previous year she had experienced increasing difficulty coping with the challenges of her job. Her bright personality had become flat – people had started to notice and gossip. The year before, her long-widowed mother had died of cancer and Natasha was sure that she had “put in enough grieving to move on”. However, she found she could get through the day only if she took a lengthy ‘desk-nap’ every lunchtime. But these secret sleeps made Natasha’s cyclic exhaustion even worse. Colleagues and family members eventually persuaded her to seek professional psychotherapy.

At her first therapy session, Natasha recounted that she often felt like being: “in a void within the blackness beyond the abyss. It’s frightening but strangely comforting – I sometimes wish I could escape into it!” After full assessment, Natasha’s psychotherapist diagnosed depression and tried a number of interventions including MBCT (Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy) [67,68]. Natasha related a recent incident: “I decided to lift my stressed and darkened soul by watching the supermoon rising at dusk. I arranged to visit a remote ocean headland I knew. I arrived all excited but within an hour, dark clouds swept in and blacked out my sky – I felt bitterly disappointed. By the time I trudged home, the black sky was pelting down with rain and I felt devastated – I really wanted to disappear into the comfort of my own abyss”. Natasha’s therapist explained that her experience was most likely the result of her thoughts escalating a minor let-down in daily life into a major personal catastrophe. Her therapist elucidated: “Some experts such as Waltman and Palermo [69] call it ‘catastrophizing’ which arises from your Sub-selves flooding your psyche with irrational thoughts about every disappointment becoming a disaster. Remember that mindchatter doesn’t become your thoughts unless you allow them so.” Over time, Natasha learnt to understand her predominant Sub-selves by using Voice Dialogue under her psychotherapist’s guidance to role-play each in turn, with her Managing-ego monitoring her ‘inner voices’ [39].

With repeated practice, Natasha mastered the central psychotherapeutic technique of passive mindfulness (via stillness meditation). Essentially, this entailed her sitting still for up to 25 minutes twice a day and focussing her attention exclusively on her breath while maintaining a completely open-minded attitude without any inner commentary. Natasha found it helpful to repeatedly recite an unvoiced mantra (‘To-tal – Calm’) to the rhythm of her breathing in order to occupy her monkey mind’s desperation for content during stillness meditation [4,70]. She also opened herself to inner stillness by allowing her Inner-observer to detachedly and non-reactively observe the inevitable distractions of her mindchattering Sub-selves without engaging them [39]. Over many weeks of such stillness meditation (i.e., passive mindfulness), Natasha was rewarded with the ‘disidentification insight’. This is the realisation that her Inner-observer (‘true self’) is separate from her depressive voices (thoughts and feelings) and, therefore, that they can be disregarded as though they were just ‘storm clouds passing’ [37]. Despite frequent back-steps, Natasha continually improved in her ability to manage her psyche and its depressive tendencies by using both the active and passive forms of mindfulness.

- Case 3: Simone (aged 18)

Simone had recently left home to study drama at an elite city college having graduated from high school with outstanding grades. Within weeks, she was referred to a psychotherapist for her high anxiety and her suicidal threats. After her fifth weekly session, Simone turned up at her therapist’s clinic at lunchtime without an appointment. She stormed past the receptionist and barged into the therapist’s office declaring: “Do I have to kill myself before you take any notice of me?” Her therapist replied calmly: “Simone, I’ll cancel everything right now and give you my total attention. Please tell me what’s happening for you”. Simone then yelled out her jumbled inner issues as her multi-voiced mindchatter spattered them across her psyche addressing: her ‘effing’ parents and siblings, her ‘disloyal’ friends, her ‘shitty’ teachers, her ‘nobody’ therapist, God herself, and the whole ‘effing’ world! Simone had previously been instructed about the tetradic model of the psyche and the concept of mindfulness, but she was unable at this point to realise that several of her Sub-selves had taken control of her psyche and that ‘anti-mindfulness’ was preventing her from gaining any detachment from her current mental chaos (Figure 1).

Simone’s psychotherapist reminded her that her Managing-ego had the capacity to detach from the mindchatter of her Sub-selves which had been numbing her ability to decide whether she really wanted to take her own life [64]. Rather than listening to her dominant Sub-selves (especially, ‘The Vulnerable’), Simone’s psychotherapist suggested that she focus on the fundamental choice she faced, namely, her currently active ‘Want-to-Live Sub-self’ versus her ‘Want-to-Die Sub-self.’ This deliberate over-simplification was adopted by her therapist to help this suicidal client clarify the confusion and chaos of their overwhelming mindchatter. A trained psychotherapist can guide a client in their binary choice about their ultimate life-versus-death decision. By applying the basic principles of Voice Dialogue [43-45,53], the psychotherapist can invite the client to role-play in turn, the part of them that wants to die versus the part that wants to live. Thus, the existential choice for the client becomes clear: ‘Yes’ versus ‘No’ in their own impending life-or-death decision. By guiding the client to separately voice out-loud these two life-competing parts of their psyche while self-monitoring via their Managing-ego (also ideally supported by the detached watchfulness of their Inner-observer), the therapist can help them make a rational and definitive choice about suicide [39]. In this case, Simone chose to live.

Note that the author used this adaptation of Voice Dialogue in three diverse cases of ‘suicide-in-progress’ (e.g., deliberate overdose) while serving part-time for six years as a trained volunteer telephone counsellor with the national crisis helpline in Australia. After extensive counselling in all three instances (as per this case example), the caller chose to live and gave their permission to be rescued by paramedics. The author acknowledges that more applied research is needed before this approach can be implemented further in suicide prevention.

Discussion

The tetradic model presented here is designed to provide therapists across multiple disciplines with relevant constructs and a framework for understanding and applying the complex dynamics of the human psyche. Others may take up its conceptual and empirical evaluation towards possible psychotherapeutic adoption [71]. The tetradic model’s four key structural constructs can be integrated with established frameworks so that psychotherapists can tailor their professional interventions to their clients’ specific needs as well as their own self-care [72,73]. The four structural self-components here proposed are: the Sub-selves which generate our endless ‘mindchatter’, the Managing-ego which oversees and controls our interactions with the external world including others, the Inner-observer which monitors our mental activity from the totally detached and neutral perspective of the ‘true self’, and the Unconscious which is acknowledged but is considered beyond the scope of the present model and its therapeutic applications (Figure 1). This tetradic model draws on other established frameworks including those of Freud [31], Miller et al. [35], Jung [32], Deikman [36], Hede [37,39], and also Stone and Stone [43,45].

The tetradic model also incorporates mindfulness, an ancient technique which has been found to be effective in treating many psychological and medical conditions [20,27,55,68]. The current approach distinguishes between two forms of mindfulness (viz., active versus passive). The first form, active mindfulness, is defined as the domain of one’s main operational self (Managing-ego) which is able to monitor and co-ordinate one’s Sub-selves that are responsible for causing major disturbances in one’s psyche including life’s ultimate crisis, that of a suicide decision. The other form (viz., passive mindfulness) is the primary function of one’s Inner-observer (or ‘true self’) which is able to keep a totally neutral watch over one’s own psyche even when it’s experiencing chaos. Without intervening directly in the daily life of one’s psyche, the Inner-observer is able to watch the often-chaotic mental activity of a disturbed individual. Unfortunately, without training or therapeutic guidance, most people are unable to harness the capacities of their Inner-observer – indeed, they have no awareness of the existence of this component of their psyche, their ‘true self.’

Further, the proposed tetradic model identifies the key mechanisms by which the two proposed forms of mindfulness can be applied in psychotherapy (Figure 1). The first mechanism is ‘decentering’ by which one’s Managing-ego can adopt active mindfulness in order to disconnect or separate from the content of their own thoughts. The second therapeutic mechanism in the proposed model is ‘disidentification’ which involves the development of awareness that one’s existential identity is not based on their most active Sub-selves with their accompanying destructive thoughts and feelings. Rather, when they achieve the insight that arises from repeated passive mindfulness (by means of stillness meditation), an individual can come to realise that their existential being centres on their true self (i.e., Inner-observer) not their troubled and over-active ‘monkey mind’.

Conclusion

The most therapeutically relevant application of the proposed tetradic model is that of Voice Dialogue which can be adapted for implementation across various disciplines including psychiatry, clinical psychology, psychotherapy, counselling and social work. The present application was derived from that originally developed by Stone and Stone [43] in the context of their Psychology of Selves [45,53]. According to the tetradic model, it is the Sub-selves that are the primary source of one’s endless thoughts or mindchatter which cause much of an individual’s mental disturbance [4,5]. This is particularly so if an individual existentially identifies with their currently dominant Sub-selves rather than with their higher self (or ‘true self’), namely, their Inner-observer. The therapeutic technique of Voice Dialogue is here described as ‘role-play’ in order to explain it clearly to patients/clients. The aim for the psychotherapist is to guide clients towards a first-hand experiential understanding of their dominant Sub-selves by inviting them to act out (role-play) their Sub-selves. They do this by vocalizing their inner ‘voices’ in turn and then using their Managing-ego to monitor and subsequently debrief with their therapist thereby gaining personal insight about their own psyche.

Finally, the three composite therapeutic case examples presented here are intended to show how the various theoretical constructs in the proposed tetradic model can be applied by enabling psychotherapists to incorporate them with other established interventions so as to effectively treat their clients across a range of personal circumstances and mental health conditions [71]. For future research it is hoped that this model may stimulate specific empirical testing of possible applications in counselling and psychotherapy. The proposed distinction between two forms of mindfulness, active versus passive, needs to be evaluated in terms of its conceptual as well as its experiential validity.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

None.

Funding

The author received no financial support for this research.

Ethics statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability

No data were collected for the research used in this article.

References

- Bhikkhu AS, Popp E (2000) Meeting the monkey halfway. York Beach ME: Samuel Weiser.

- Chodron T (2004) Taming the mind. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications.

- Mikulas WL (2014) Taming the drunken monkey: The path to mindfulness, meditation, and increased concentration. Woodbury MN: Llewellyn Publications.

- Smith D (2012) Monkey mind: A memoir of anxiety. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Ferguson L (2013) Three keys to unlocking inner peace. Interbeing 6: 15-17.

- Eliuk K, Chorney D (2017) Calming the monkey mind. International Journal of Higher Education 6: 1-7.

- Analayo B (2021). The dangers of mindfulness: Another myth? Mindfulness 12: 2890-2895.

- Kabat-Zinn J (1982) An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 4: 33-47.

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990) Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Bantam Dell.

- Karunamuni N, Weerasekera R (2019) Theoretical foundations to guide mindfulness meditation: A path to wisdom. Current Psychology 38: 627-646.

- Nhat Hanh T (1975) The miracle of mindfulness: An introduction to the practice of meditation. Boston MA: Beacon Press.

- Stanley S (2012) Intimate distances: William James’ introspection, Buddhist mindfulness and experiential inquiry. New Ideas in Psychology 30: 201-211.

- Baminiwatta A, Solangaarachchi I (2021) Trends and developments in mindfulness research over 55 years: A bibliometric analysis of publications indexed in Web of Science. Mindfulness 12: 2099-2116.

- Phang CK, Oei TPS (2012) From mindfulness to meta-mindfulness: Further integration of meta-mindfulness concept and strategies into cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mindfulness 3: 104-116.

- Chiesa A, Serretti A (2009) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 15: 593-600.

- Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, Benson H, Fricchione GL, et al. (2015) Standardized mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One 10: 1-17.

- Kabat-Zinn J (2011) Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. Contemporary Buddhism 12: 281-306.

- Elices M, Pérez-Sola V, Pérez-Aranda A, Colom F, Polo M, et al. (2022) The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Primary Care and the Role of Depression Severity and Treatment Attendance. Mindfulness 13: 362-372.

- Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, Whalley B, Crane C, et al (2016) Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: An individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry 73: 565-574.

- Segal ZV, Williams JM, Teasdale JD (2002) Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JM, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, et al. (2000) Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 68: 615-623.

- Williams K, Hartley S, Taylor P (2021. A Delphi study investigating clinicians’ views on access to, delivery of, and adaptations of MBCT in the UK clinical settings. Mindfulness 12: 2311-2324.

- Yela JR, Crego A, Buz J, Sánchez-Zaballos E, Gómez-Martínez MÁ (2022) Reductions in experiential avoidance explain changes in anxiety, depression and well-being after a mindfulness and self-compassion (MSC) training. Psychol Psychother 95: 402-422.

- Baer RA (2006) Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: Clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications. Burlington MA: Academic Press.

- Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, Davidson RJ, Wampold BE, et al. (2018) Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 59: 52-60.

- Yip ALK, Karatzias T, Chien WT (2022) Mindfulness-based interventions for non-affective psychosis: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 54: 2340-2353.

- Bursky M, Kosuri M, Walsh Carson K, Babad S, Iskhakova A, et al. (2023) The utility of meditation and mindfulness-based interventions in the time of COVID-19: A theoretical proposition and systematic review of the relevant prison, quarantine and lockdown literature. Psychol Rep 126: 557-600.

- Somaraju LH, Temple EC, Bizo LA, Cocks B (2021) Brief mindfulness meditation: Can it make a difference? Current Psychology 42: 5530-5542.

- Morris SJ (2003) A metamodel of theories of psychotherapy: A guide to their analysis, comparison, integration and use. Clin Psychol Psychother 10: 1-18.

- Cherry K (2022) Id, Ego, and Superego: Freud's Elements of Personality.

- Freud S (1960) The Ego and the Id. WW Norton & Company, USA.

- Jung CG (1970) Structure and dynamics of the psyche. In Adler G, Hull RFC (Eds.). Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Princeton University Press, USA.

- Miller JP (2007) A unified model of the human psyche. LuLu Enterprises Inc, USA.

- Pinheiro IMR (2014) A new model for the human psyche. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science 2: 61-65.

- Miller AA, Isaacs KS, Haggard EA (1965) On the nature of the observing function of the ego. British Journal of Medical Psychology 38: 161-169.

- Deikman AJ (1982) The observing self: Mysticism and psychotherapy. Beacon Press, USA.

- Hede AJ (2010) The dynamics of mindfulness in managing emotions and stress. Journal of Management Development 29: 94-110.

- Hede AJ (2017) Using mindfulness to reduce the health effects of community reaction to aircraft noise. Noise & Health 19: 165-173.

- Hede AJ (2018) Binary model of the dynamics of active versus passive mindfulness in managing depression. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine 3: 1-28.

- Brand RM, Badcock JC, Paulik G (2022) Changes in positive and negative voice content in cognitive-behavioral therapy for distressing voices. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 95: 807-819.

- Amaro A (2021) Mindfulness of emotions and thoughts, and the non-location of mind. Mindfulness 12: 2832-2838.

- Ford CG, Kiken LG, Haliwa I, Shook NJ (2021) Negatively biased cognition as a mechanism of mindfulness: A review of the literature. Current Psychology 42: 8946-8962.

- Stone H, Stone S (1989) Embracing our selves: The voice dialogue manual. New World Library, USA.

- Hoffman D (2012) The voice dialogue anthology: Explorations of the Psychology of Selves and the aware ego process. Delos Inc, USA.

- Stone H, Stone S (2012) The basic elements of voice dialogue, relationship, and the Psychology of selves: Their origins and development. In: Hoffman D (Ed.). The voice dialogue anthology: Explorations of the Psychology of selves and the aware ego process. Delos Inc, USA.

- Casement A (2006) The shadow. In: Popadopoulos KR (Ed.). The handbook of Jungian Psychology: Theory, practice and applications. Taylor & Francis, UK.

- Jung CG (1968) AION: Researches into the phenomenology of the self. In: Read H, Fordham M, Adler G, McGuire W (Eds.). The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Routledge & Kegan Paul, USA.

- Waldron WS (2006) The Buddhist unconscious. Taylor and Francis, UK.

- Ekstrom SR (2004) The mind beyond our immediate awareness: Freudian, Jungian, and cognitive models of the unconscious. The Journal of Analytical Psychology 49: 657-682.

- Bargh JA (2019) The modern unconscious. World Psychiatry 18: 225-226.

- Freud S (2005) The Unconscious. Penguin Classics, USA.

- Berchik Z, Rock A, Friedman H (2012) Allow me to introduce my selves: An introduction to and phenomenological study of Voice Dialogue Therapy. In: Hoffman D (Ed.). The voice dialogue anthology: Explorations of the Psychology of selves and the aware ego process. Delos Inc, USA.

- Dyak M (1999) The voice dialogue facilitator’s handbook. Energy Press, USA.

- Fletcher L, Hayes SC (2005) Relational frame theory, acceptance and commitment therapy, and a functional analytical definition of mindfulness. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 23: 315-336.

- Kabat-Zinn J (1994) Wherever you go, There you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion, USA.

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L (2006) Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 13: 27-45.

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, et al. (2004) Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr 11: 230-241.

- Deshmukh VD (2006) Neuroscience of meditation. The Scientific World Journal 6: 2239-2253.

- D’Errico L, Call M, Blanck P, Vonderlin E, Bents H, et al. (2019) Associations between mindfulness and general change mechanisms in individual therapy: Secondary results of a randomised controlled trial. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 19: 419-430.

- Maddock A, Blair C (2021) How do mindfulness-based programmes improve anxiety, depression and psychological distress? A systematic review. Current Psychology 42: 10200-10222.

- Bernstein A, Hadash Y, Lichtash Y, Tanay G, Shepherd K, et al. (2015) Decentering and related constructs: A critical review and metacognitive processes model. Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 599-617.

- Salem MB, Karlin NJ (2023) Dispositional mindfulness and positive mindset in emerging adult college students: The mediating role of decentering. Psychological Reports 126: 601-609.

- Martin S (2023) Why using ‘consciousness’ in psychotherapy? Insight, metacognition and self-consciousness. New Ideas in Psychology 70: 1-9.

- Aronson J, Blanton H, Cooper J (1995) From dissonance to disidentification: Selectivity in the self-affirmation process. Journal of Personality Social Psychology 68: 986-996.

- Corstens D, Longden E, May R (2012) Talking with voices: Exploring what is expressed by the voices people hear. Psychosis: Psychological, Social and Integrative Approaches 4: 95-104.

- Strachan LP, Paulik G, McEvoy PM (2022) A narrative review of psychological theories of post-traumatic stress disorder, voice hearing, and other psychotic symptoms. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 29: 1791-1811.

- Britton WB, Davis JH, Loucks EB, Peterson B, Cullen BH, et al. (2018). Dismantling mindfulness-based-cognitive therapy: Creation and validation of 8-week focused attention and open monitoring interventions within a 3-armed randomized controlled trial. Behavior Research and Therapy 101: 92-107.

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT (2006) The empirical status of cognitive behavior therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review 26: 17-31.

- Waltman SH, Palermo A (2019) Theoretical overlap and distinction between rational emotive behavior therapy’s awfulizing and cognitive therapy’s catastrophizing. Mental Health Review Journal 24: 44-50.

- Main J (2012) Twelve talks for meditators - Meditatio Talks Series. WCCM Medio Media Publishing, UK.

- Loewenthal D (2020) Critical existential-analytic, rather than ‘evidence based,’ psychotherapies: Some implications for practices, theories and research (Editorial). European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling 22: 1-8.

- Chopko BA, Papazoglou K, Schwartz RC (2018) Mindfulness-based psychotherapy approaches for first responders: From research to clinical practice. American Journal of Psychotherapy 71: 55-64.

- Christopher JC, Maris JA (2010) Integrating mindfulness as self-care into counselling and psychotherapy training. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 10: 114-125.

- McCabe R, Day E (2020) Counsellors’ experiences of the use of mindfulness in the treatment of depression and anxiety: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 22: 166-174.

Citation: Hede AJ (2024) Tetradic Model of the Human Psyche Incorporating Active versus Passive Mindfulness with Psychotherapeutic Applications. J Altern Complement Integr Med 10: 445.

Copyright: © 2024 Andrew J Hede, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.