The Effectiveness of Responsible Beverage Service Training Programs: A Literature Review and Synthesis

*Corresponding Author(s):

James C FellNORC At The University Of Chicago, 4350 East-West Highway, 8th Floor, Bethesda, Maryland 20814, United States

Tel:+ 301-634-9576,

Email:fell-jim@norc.org

Abstract

- Background

Studies have revealed that approximately half of driving while intoxicated (DWI) offenders had their last alcoholic drink at a licensed bar or restaurant. Sales and service of alcohol to underage youth and those already intoxicated contributes to many causes of injuries. The objective of this study was to conduct a comprehensive literature review and synthesis of responsible beverage service (RBS) training effectiveness and to document the various measures of effectiveness.

- Methods

This review was conducted to understand the effects of RBS training on various alcohol measures of harm and in particular reducing alcohol-impaired driving. The review included both peer-reviewed and grey literature resources. Professional association websites were also searched in an effort to seek information on the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of RBS training as a strategy to reduce alcohol-related harms.

- Results

Twenty-four articles found RBS training to be effective in reducing some measure of alcohol harm. Six articles could not find an effect for RBS training and eleven articles only described the implementation process of RBS training programs. Successful RBS training programs had effects on at least ten measures of alcohol harm (e.g., sales to pseudo-intoxicated patrons (decreased); DWI arrests coming from bars (decreased); and assault injuries treated at the emergency department (decreased) as examples). Reasons for RBS training being ineffective included (a) lack of buy-in by managers and owners, (b) no incentive for servers to deny service, (c) no enforcement of illegally serving underage or visibly intoxicated patrons and (d) poor implementation of the training program.

- Conclusion

There are strong indications that RBS training, when implemented correctly, when sustained, when owners and managers buy into the strategy and when implemented in coordination with other interventions, can substantially reduce a number of harms due to risky alcohol consumption.

Keywords

Aggression; Alcohol harms; Assaults; Driving while intoxicated; Effectiveness; Pseudo-intoxicated patrons; Responsible beverage Service training; Single vehicle nighttime crashes

Background

- Global Alcohol-Related Harm

The World Health Organization [1] in 2016 reported that harmful alcohol use resulted in 3 million deaths which was 5.3% of all global deaths. Of the 3 million deaths attributable to alcohol, 28.7% were due to injuries, 21.3% due to digestive diseases, 19% due to cardiovascular diseases, 12.9% due to infectious diseases, 12.6% due to cancers and the remaining 5.5% due to other causes. Worldwide, alcohol was responsible for 7.2% of all premature (69 years and younger) mortality in 2016. Alcohol disproportionately affected younger persons with 13.5% of all deaths among those aged 20–39 years being attributed to alcohol. Globally in 2016, an estimated 900,000 injury deaths were attributable to alcohol, including 370,000 deaths due to motor vehicle crashes, 150,000 due to self-harm and an estimated 90,000 due to interpersonal violence. Of the deaths due to motor vehicle crash injuries, 187,000 of the alcohol-attributable deaths were among people other than the alcohol-involved drivers. In comparison to other regions, the alcohol-attributable disease burden was highest in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. [2] reviewed evaluation studies concerning the effectiveness of interventions in and around licensed premises that aimed to reduce severe intoxication and disorder. Fifteen studies were identified, three randomized controlled trials and 12 non-randomized quasi-experimental evaluations. Outcome measures were intoxication (n = 6), disorder (n = 6) and intoxication and disorder (n = 3). Interventions included responsible beverage service (RBS) training (n = 5), server violence prevention training (n = 1), enhanced enforcement of licensing regulations (n = 1), multi-level interventions (n = 5), licensee agreements (n = 2) and a risk-focused consultation (n = 1). The effects of the interventions varied considerably, even across evaluations using similar interventions. The authors concluded that server training courses that are designed to reduce alcohol disorder have some potential. However, there was a lack of evidence to support their use to reduce intoxication and the evidence base was weak. It has been 13 years since the [2] study. This current literature review and synthesis will provide an update on the studies that used RBS training with an emphasis on preventing impaired driving.

- Global Drink-Driving

Globally, road traffic crashes kill about 1.35 million people yearly. Road crashes also result in substantial socioeconomic losses and emotional consequences for the victims and their families. As a result, road safety has received greater attention in the international community and has become a global development agenda issue. In 2010, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly proclaimed 2011 to 2020 as the Decade of Action for Road Safety. WHO, in the 2018 report on the global status of road safety, recommended four policies to reduce impaired driving:

- adoption of a national drink-driving law;

- setting alcohol concentration limits for adult drivers at .05%;

- setting zero alcohol limits for young novice drivers; and

- conducting random breath testing similar to that as originated in Australia, as the key enforcement strategy [3].

A Minimum Legal Drinking Age (MLDA) in countries reduces impaired driving crash fatalities among the youth; especially an MLDA of 21 [4-6]. In most countries, the MLDA is 18, however, United States (USA), Indonesia, Micronesia and Palau have established theirs at 21. Most RBS training programs include strategies to prevent serving alcohol to underage patrons. Alcohol-impaired driving and speeding commonly occur in combination. Typically, 30%-50% of impaired driving fatal crashes involve speeding and about 20%-40% of speeding fatal crashes involve alcohol [7]. One study in India identified “drunken driving and over-speeding” as the two major causes of traffic fatalities in India and recommended banning advertisements glamorizing alcohol and encouraging excessive drinking [8].

- Impaired Driving in the United States

Impaired driving is a substantial public health and public safety problem especially in the USA, Canada and Europe. In 2019, there were 36,096 traffic fatalities in the USA with 10,142 of those fatalities (28%) involving a legally intoxicated driver with a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) greater than or equal to 0.08 grams per deciliter.The costs to society of alcohol-related crashes exceeded $125 billion in 2010 [9]. Impaired driving traffic fatalities have increased in the USA in 2020 to 11,654 and again in 2021 to 13,384 [10]. Most impaired driving countermeasures are implemented at the state and local community levels in the USA [11,12]. Many factors account for the increased risk of drinking-driver fatalities among young adults, particularly consumption of larger amounts of alcohol on a single occasion. As BAC levels increase, the chances of crash involvement rise. [13] showed that males aged 21 to 34 with BACs of .08 to .09 were 13 times more likely to be killed in a single-vehicle crash than sober (BAC=.00) male drivers of the same age. At BACs of .15 or greater, 21- to 34-year-old males were 573 times more likely to be killed in a single-vehicle crash compared to their same-aged counterparts with no alcohol. In a review of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), alcohol-impaired driving was most frequent among males aged 21 to 34 (1,739 episodes per 1,000 adults) compared to the average of 655 episodes per 1,000 adults for all ages [14].

- Heavy Episodic Drinking

Studies have revealed that approximately half of the intoxicated drivers had their last drink at a licensed bar or restaurant [15-19]. Except in a few jurisdictions in the USA, the service of alcohol to intoxicated patrons is prohibited by state or local law as well as liquor control regulation. Additionally, “dram shop” laws in most states in the USA allow injured third parties to recover damages from licensed establishments in crashes resulting from the service of alcohol to intoxicated patrons. Several other states have dram shop laws that apply only to underage drinkers [20]. Given the high proportion of alcohol-impaired drivers who come from licensed establishments, it is evident that these legal measures have not prevented intoxicated patrons from being served or from leaving licensed establishments in an intoxicated condition. Since the 1980s, restricting alcohol at the point of sale has increased as a strategy to reduce impaired-driving-related traffic crashes and other consequences of alcohol misuse [21] provided the conceptual framework for designing one such strategy: a server intervention training program. Server intervention refers to those actions taken by servers of alcoholic beverages, designed to reduce the likelihood that those being served will harm themselves or others. Server programs can be divided conceptually into three components:

(1) Training (educational programs directed at servers);

(2) Legal (Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC) laws and regulations including dram shop liability and criminal laws): and

(3) Environmental (design of the alcohol outlet, outlet location, outlet density, food service and transportation availability).

[21] Analyzed these three components and reviewed six existing or completed programs throughout the USA. He concluded by summarizing the practical barriers, potential benefits and theoretical implications of a server intervention approach to the prevention of alcohol-impaired driving. [22] Summarized the alcohol policy issues in the USA and concluded that drinking by underage youth and those already substantially impaired or intoxicated continue as major contributors to alcohol-related car crashes. To prevent alcohol-related problems, states have made it illegal for licensed alcohol establishments to sell alcohol to underage youth (all states) or to customers who show obvious signs of intoxication (most states). However, despite existing laws, many alcohol establishments, both off-premise (i.e., liquor and grocery stores) and on premise (i.e., bars and restaurants), have serving practices that foster high-risk drinking behavior. Extant literature indicates that servers at alcohol establishments rarely intervene to prevent intoxication or refuse service to intoxicated patrons. This lack of intervention is reflected in studies noting that pseudo-intoxicated patrons can purchase alcohol in 62% to 90% of purchase attempts [22]. Additionally, evidence suggests that approximately a third of patrons leaving bars have BACs above the legal limit for driving and between one-third and three-quarters of intoxicated drivers consumed their last alcoholic beverage at a bar. Sales and service of alcohol to youth and those already impaired or intoxicated (also referred to as over service) contributes to many health problems, both those related to driving and other incidents. For example, alcohol is involved in approximately 30% of fatal traffic crashes, 76% of fatal traffic crashes between midnight and 3 a.m., 76% of rapes, 66% of violent incidents between intimate partners, 30% to 70% of drownings, 50% of homicides, 50% of assaults and 38% of suicides [22]. Not serving alcohol to those already substantially impaired by alcohol is a clear avenue to reduce traffic crashes and other health and social problems resulting from heavy episodic drinking.

- Responsible Beverage Service

One countermeasure program that began in the 1980s in the USA, Australia, Canada and Scandinavian countries is RBS training. The theory behind RBS is that if alcohol servers can be trained to refuse service to underage youth and obviously intoxicated patrons, the harms due to alcohol can be reduced, including impaired driving [23]. Examined the effectiveness of interventions implemented in drinking environments to reduce alcohol use and associated harms. The findings of the review were limited by the methodological shortcomings of most of the included studies. However, three studies indicated that multicomponent programs combining community mobilization, RBS training, restrictive house policies and stricter enforcement of licensing laws could be effective in reducing alcohol-fueled assaults, alcohol-related traffic crashes and underage customer sales depending on the focus of the intervention. The authors concluded that the effectiveness of many interventions was limited and that future studies should focus on the use of appropriate and robust study designs. RBS programs are usually supported by legislation or local alcohol policies and are designed to train servers in licensed establishments. The training program typically involves requiring an Identification (ID) of age check on young patrons, recognizing fake IDs, detecting obviously intoxicated and/or excessive drinking patrons and refusing alcohol service to them and practicing interventions that are safe and acceptable to customers who might have too much to drink. Theoretically, RBS training programs have the potential to not only reduce alcohol-impaired driving and alcohol-related crashes, but can be effective in reducing drunkenness, violence, assaults and injuries. The objective of this study was to conduct a comprehensive literature review and synthesis of the studies of RBS training effectiveness and to determine the various measures of effectiveness. While the main goal was to determine if there is evidence on whether RBS can reduce alcohol-impaired driving, studies involving the impact of RBS on other measures were also accepted for review. These measures include, but are not limited to, RBS effects on underage drinking, on patron intoxication, on violence (including fights and assaults), on domestic violence, on calls for service, on driving-while-intoxicated (DWI) arrests, on public drunkenness, on alcohol consumption and on alcohol sales.

Methods

To better understand the effects of RBS on various alcohol measures and in particular reducing impaired driving, a review of the existing literature was conducted including both peer-reviewed and grey literature resources such as government reports, unpublished manuscripts and working papers. Professional association websites were also searched. The review was guided by pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria that identified the scope and key terms that were used when searching the literature. Specifics of the process included identifying relevant databases to be searched; using multiple search engines to find relevant materials; and drawing upon colleagues and experts in the field to identify additional resources such as manuscripts under review.

Databases and Search Engines

Full and free access to the University of Chicago Library’s extraordinary collection facilitated the literature search. The University of Chicago Library is the 10th largest research library in North America with 11.3 million volumes in print and electronic form, as well as its numerous subscription-based bibliographic and full text electronic databases in the biological, medical, social and behavioral sciences. Among these are Articles Plus, Cochrane Library (Wiley) Medline, ISI Web of Science, ProQuest, PsycINFO, Social Services Abstracts and WorldCat. Available subscription databases include Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Scopus and others. Additional electronic resources were identified through the University of Chicago Library’s Database Finder. This database served as the main source of the literature review. Additionally, some sources were identified through the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA’s) Behavioral Safety Research Reports Library and the Transportation Research International Documentation Database (TRID) encompassing the Transportation Research Information Services (TRIS) and International Transport Research Documentation (ITRD) databases.

Conference papers, congressional papers or briefs and grey literature were identified by investigating professional organization websites, such as the Transportation Research Board (TRB), International Council on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety (ICADTS), Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (HFES), Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine (AAAM), International Traffic Medicine Association (ITMA), International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and the Governor’s Highway Safety Association (GHSA). Additionally, research published by other credible institutions, e.g., Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety (AAAFTS), Society of Forensic Toxicologists (SOFT), American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS), The International Association of Forensic Toxicologists (TIAFT) and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) were scanned. Google Scholar served as an additional resource to locate articles that were not easily accessible in the previously listed databases. In some instances, Google Scholar was also used to conduct “backward” literature searches to determine if a source was used in another relevant article or report.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

References identified in the literature search were exported to an Excel document. Each abstract was reviewed to determine the relevancy of the documents. Copies of the documents that were deemed relevant by the title and abstract review were retained. The next level of screening and reviewing of the documents was applied to determine which should be included. Criteria included:

- Whether the research results appear invalid or questionable because of insufficient sample size, confounding variables, inappropriate data analyses, or other problems, in which case the document was excluded.

- Articles primarily discussing opinions were excluded, with few exceptions. Articles presenting evidence based on scientific data and new data on the efficacy of RBS training were included.

- Articles published between 1980 and 2020 and were written in English, were included.

Synthesis and Analysis of Findings

Critical analysis and synthesis involved consideration of the conceptual and methodological strengths and weaknesses of the studies under review, relating the sources to each other and to the purpose of the research, identifying areas of convergence and divergence as well as knowledge gaps that the review addresses. Synthesis required critical evaluation and interpretation of studies to draw conclusions about the findings in the literature. Information was analyzed and summarized in an objective manner, using illustrations (e.g., examples that represent key findings that emerged across the documents) as appropriate. All resources identified by the search process and review were relevant to responsible beverage service.

Key Words Used

The following key words were used in the search, most in combination with other key words:

- Responsible Beverage Service (RBS) Training;

- Effectiveness of RBS;

- Enforcement of Alcohol Service Policies;

- Obviously Intoxicated;

- Drunkenness; Selling or Providing Alcohol to an Underage Patron; Refusal of Alcohol Service;

- On-line RBS Training;

- e-TIPS;

- Place of Last Drink (POLD);

- Problem Bars;

- Calls for Service;

- Driving While Intoxicated (DWI) Offenders;

- Driving Under The Influence (DUI) Arrests;

- DUI offenders;

- Alcohol-impaired driving;

- Alcohol-related Crashes/Injuries/Fatalities;

- Alcohol-Impaired Drivers/Offenders;

- Over-Service of Alcohol;

- Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) of Bar Patrons;

- Disorderly Conduct;

- Alcohol Sales;

- Homicides;

- Shootings;

- Fights; Age

- Identification (ID)

- Scanners;

- Pseudo-Bar-Patrons;

- Signs of Intoxication;

- Alcohol Service Practices;

- Intervention;

- Customer Interaction;

- Bartenders;

- Waiters;

- Waitresses;

- Managers;

- Owners;

- Server Intervention Programs;

- Skills Training;

- Slow-Down The Service of Alcohol;

- Recognizing Signs of Intoxication;

- Slurred Speech;

- Fumbling With Wallet;

- Tracking Number of Drinks Served;

- Offering Food and Nonalcoholic Beverages;

- Arranging A Safe Ride Home;

- Reduction In Drinking;

- Alcohol Abstinence.

Relevant Literature

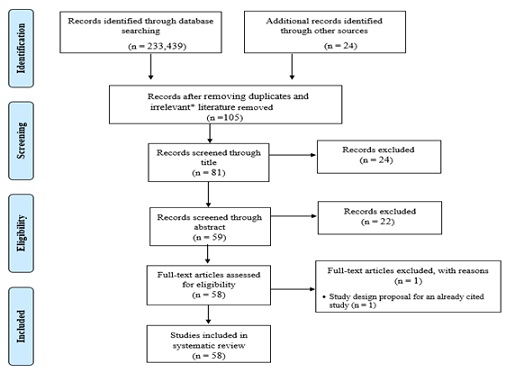

Initially, using all the key words, 233,439 articles emerged. However, following the procedures and methods provided above, the number of articles were reduced to 105. After applying the exclusion criteria discussed above and eliminating further articles or sources during the thorough review, a total of 58 articles, reports, conference papers and other gray literature (e.g., policy statements or professional association articles) were included. The bibliography contains a citation of the report, article, or document using the APA 6th Edition Style Manual.

Table 1 shows the number of articles discovered by topic. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Methodology Flow Diagram.

|

Literature Topics |

Counts |

|

Multi-component interventions (e.g., RBS plus enforcement and media campaigns) |

22 |

|

Reduce drink driving (e.g., main focus) |

21 |

|

International programs (e.g., conducted outside the USA) |

21 |

|

Education/Training (e.g., sample programs, recommendations for implementation) |

20 |

|

Reduce overserving |

12 |

|

Reduce assaults/aggression |

12 |

|

Perceptions or beliefs (e.g., manager or server perceptions of RBS, service behaviors) |

12 |

|

Service to underage youth |

9 |

|

Effectiveness of laws and regulations (e.g., RBS, over-service, etc.) |

7 |

|

Systematic Reviews |

6 |

|

Events and festivals (e.g., main focus) |

5 |

|

College student behaviors (e.g., reduce over consumption on college campuses) |

3 |

Table 1: Articles Identified by Topic.

Figure 1: PRISMA Methodology Flow Diagram. *University of Chicago’s database yielded over 200,000 results based on our search terms. However, a majority of those records found through this initial search were not relevant to the actual study and only addressed a portion of the Boolean string search. For instance, some literature that came up in University of Chicago database for “responsible beverage service AND over-service” may have only included the term “responsible” or “beverage” or “service” but in fact was not about responsible beverage service or over-service of alcohol.

Figure 1: PRISMA Methodology Flow Diagram. *University of Chicago’s database yielded over 200,000 results based on our search terms. However, a majority of those records found through this initial search were not relevant to the actual study and only addressed a portion of the Boolean string search. For instance, some literature that came up in University of Chicago database for “responsible beverage service AND over-service” may have only included the term “responsible” or “beverage” or “service” but in fact was not about responsible beverage service or over-service of alcohol.

Results

RBS Effective

Twenty-four studies conducted over the past 30 years were assessed as using acceptable evaluation methods and showed at least some positive effects of RBS training. Some examples of the better studies follow:

[24] assessed the effects of enforcing laws prohibiting the service of alcohol to already intoxicated patrons of bars and restaurants. Following introduction of an education and enforcement effort in Washtenaw County, Michigan, observed refusals of service to pseudo-intoxicated- patrons feigning intoxication increased significantly from 17.5% to 54.3%, but then eventually declined to 41.0%. The percentage of drivers arrested for Driving While Intoxicated (DWI) coming from bars and restaurants declined from 31.7% to 23.3%. In a comparison county, refusals of service to pseudo-intoxicated-patrons did increase, but to a significantly smaller extent, from 11.5% to 32.7%, while the percentage of DWIs coming from bars and restaurants showed no significant differences. The analyses also revealed that service refusals were related to the volume of business and numbers of intoxicated patrons in an establishment at the time of observation, while numbers of arrested DWI offenders were related to the nature of the establishment's clientele, their policies and normal practices.

Evaluated the effect of community-based environmental interventions in reducing the rate of high-risk drinking and alcohol-related motor vehicle injuries and assaults [11]. Using a longitudinal multiple time series of three matched intervention communities, the researchers evaluated the following interventions:

- Mobilize the community;

- Encourage responsible beverage service in the bars and restaurants;

- Reduce underage drinking by limiting access to alcohol;

- Increase local enforcement of drinking and driving laws; and

- Limit access to alcohol by using zoning restrictions.

Population surveys revealed that the (a) self-reported amount of alcohol consumed per drinking occasion declined 6% from 1.37 to 1.29 drinks, (b) self-reported rate of having had too much to drink declined 49% from 0.43 to 0.22 times per six-month period and (c) self-reported driving when over the legal limit was 51% lower (0.77 vs 0.38 times) per six-month period in the intervention communities relative to the comparison communities. Traffic data revealed that, in the intervention vs comparison communities, nighttime injury crashes declined by 10% and crashes in which the police reported that the driver had been drinking declined by 6%. Assault injuries observed in emergency departments declined by 43% in the intervention communities vs the comparison communities and all hospitalized assault injuries declined by 2%. The researchers concluded that a coordinated, comprehensive, community-based intervention can reduce high-risk alcohol consumption and alcohol-related injuries resulting from motor vehicle crashes and assaults.

In a study conducted in two communities, found that RBS training plus enforcement reduced the incidence of bar patron intoxication (and potential impaired driving). In both communities [25], 10 popular bars received RBS training followed up with enforcement while 10 similar popular bars received no training, but outcome data on patrons were collected. The intervention bars performed significantly better than the control bars in terms of changes in average BACs of exiting bar patrons and the proportion of patrons exiting the bars who were intoxicated. The intervention had a similar effect on reducing the proportion of drivers who reported driving “after drinking too much” and an increase in the proportion of bar staff who refused service to pseudo-intoxicated-patrons in intervention bars. The RBS training included instructions on the following signs of intoxication:

- Loss of dexterity, e.g. fumbling with billfold, change, or drinking glasses;

- Lack of balance, e.g. stumbling, having to prop oneself up, slipping from bar stools

- Poor distance perception, e.g. over- or under-reaching, missing chair or barstool;

- Slurring of speech, e.g. very poor articulation, stretching out syllables, particularly “s”;

- Hostility, e.g. showing unwarranted or extreme anger, threatening fights;

- Extreme profanity, e.g. highly profane language, particularly in sedate company; and

- Lack of inhibitions, e.g. intruding on strangers, revealing confidences, other very inappropriate activity.

The training also included the following reasonable efforts to prevent customer intoxication:

- Offering food;

- Providing alternative transportation;

- Cutting off a patron;

- Enlisting help from the patron’s friends;

- Serving water or soda on the house;

- Measuring alcoholic drinks;

- Checking IDs; and

- Calling the police (last resort).

The study indicated that when bar managers and owners were aware of the program and the enforcement of it and servers were properly trained in RBS, fewer patrons become highly intoxicated (i.e., over-served) and an effort was made to deny service to obviously intoxicated patrons. The authors concluded that, given that about half of drivers arrested for DWI are coming from licensed establishments in any given community, if implementation of this strategy is widespread, it could have an effect on reducing alcohol attributable harm table 2.

[26] conducted a systematic review to determine the effectiveness and economic efficiency of multicomponent programs with community mobilization for reducing alcohol-impaired driving. The multicomponent programs generally included a combination of efforts to limit access to alcohol (particularly among youth), responsible beverage service training, sobriety checkpoints or other well-defined impaired driving enforcement efforts, public education and media advocacy designed to gain the support of both policymakers and the general public for reducing alcohol-impaired driving. Six studies of programs qualified for the review. Two studies examined fatal crashes and reported declines of 9% and 42%; one study examined injury crashes and reported a decline of 10%; other study-examined crashes among young drivers aged 16–20 years and reported a decline of 45%; and one study examined single-vehicle late night and weekend crashes among young male drivers and reported no change. The sixth study examined injury crashes among underage drivers and reported small net reductions. The authors concluded that the six studies reviewed provided strong evidence that carefully planned, well-executed multicomponent programs, when implemented in conjunction with community mobilization efforts and RBS training, were effective in reducing alcohol-related crashes. Three studies reported economic evidence that suggests that such programs produce cost savings Table 2.

|

Setting |

Focus |

Study Design |

Measures |

Findings |

|

|

[27] |

Six coalitions in South Carolina, USA |

Getting To Outcomes-Underage Drinking (GTO-UD) ability to improve two common EAP strategies, RBS training and compliance checks |

RCT |

Interview of prevention quality (knowledge of training); pre- and post- merchant survey (attitudes and behaviors) |

Modest findings showed that GTO-UD coalitions improved with regard to compliance checks and refusing sales to minors. However, there were no significant differences in attitudes and behaviors between the treatment and control coalitions. |

|

[25] |

Two communities (Cleveland, OH and Monroe County, NY) USA |

RBS training plus enforcement’s effect on reducing bar patron intoxication and potential impaired driving |

RCT |

Place of last drink (POLD) data from alcohol violators, calls-for-service, pseudo-patron observations, BACs of patrons, DWI arrests of 21-34 year olds and police reported alcohol-involved crashes |

RBS training plus enforcement resulted in reduced over-service in Cleveland within 6 months of the intervention (for some measures) and took a year in Monroe County. |

|

[28] |

Redlands, CA USA |

Responsible Redlands program effect on reducing DUI, underage drinking and driving, public intoxication and alcohol-related calls for service |

Process and time-series analysis |

DUI arrests, underage drinking violations, public intoxication violations, alcohol calls for service and place of last drink (POLD) data from alcohol violators |

There was a statistically significant decrease in DUI arrests for drivers 21 and older from preintervention to postintervention (p < .001). There were also decreases in underage drinking violations and in DUIs for under age 21 drivers, but the numbers were too small for chi-squared statistical tests. |

|

[29] |

Lexington County, South Carolina USA |

Effectiveness of a prevention intervention in Lexington County intended to reduce alcohol over-service and drinking and driving crashes |

Longitudinal, QED |

Media exposure, place of last drink (POLD) from drivers arrested for DUI, monthly DUI/drinking and driving crashes |

Total number of DUI crashes decreased following the last month of the intervention training. |

|

[30] |

Toronto, Ontario Canada |

Evaluate the effectiveness of the Safer Bars intervention, developed to reduce aggression in bars. |

RCT |

Pre- and post-intervention observations at bars and clubs, rates of severe aggression, moderate physical aggression |

Program bars experienced an average decrease in physical aggression by patrons, but not all were statistically significant (significant at less than .05 for definite intent and severe aggression). However, similar findings were not found in staff due to turnover and lower numbers. |

|

[60] |

South Carolina, Northern California and Southern California USA |

Evaluation of the Underage Access Component of the Community Trials Project (RBS, enforcement of underage sales laws and media) to prevent underage drinking |

Matched comparison |

Pre- and post-purchase survey data |

Results showed that increased enforcement combined with media advocacy was effective in reducing sales to minors. While it appeared that RBS training had no effect, the author noted this could be due to the small number of trained outlets in the communities studied. |

|

[31] |

“Mystery shopper” intervention in 16 communities in four USA states (California, Massachusetts, Texas and Wisconsin) |

Underage drinking |

Cluster randomized cross-over trial |

Mystery shopper inspections to observe age-verification and behavior |

Combined ID checking rates (on- and off-premise sales) increased significantly. However, On-premise outlets were more likely to check IDs than off-premise outlets. |

|

[32] |

Oregon USA |

Effects of state mandated server-training policy on traffic crashes |

Interrupted time-series |

Frequency of traffic crashes, number of traffic crashes each month where the driver had BACs>.00, single-vehicle nighttime injury-producing crashes |

Statistically significant reduction in single-vehicle nighttime traffic crashes (reduced by 11% the first year, 18% the second year and 23% by the third year). |

|

[11] |

South Carolina, Northern California and Southern California USA |

Effects of community-based environmental interventions (including RBS) on reducing the rate of high-risk drinking and alcohol-related crashes and assaults |

Longitudinal, multiple time-series, matched comparison |

Phone surveys |

Self-reported data showed that fewer survey participants engaged in risky alcohol behavior from pre- to post-. Traffic data and assault injury data showed that there were fewer crashes and fewer assault injuries in the ER (for the program areas). |

|

[33] |

Park City, UT USA |

Effectiveness of state-certified RBS training program on drinking behaviors |

RCT |

Observations of ID-checking practices, survey to assess knowledge and behavior, implementing practices to discourage over-service (e.g., signs and posters) |

Staff exhibited increased knowledge in practices and improved their behaviors and program sites were more successful in promoting safe drinking behaviors than control sites. However, observations indicated that there was not much difference in overservice between the two groups. |

|

[34] |

Bars on 12 university campuses Sweden |

Decrease in BAC and rowdy social behaviors on university campuses |

RCT |

BAC, social atmosphere (rowdy, cozy, social) |

RBS training led to decreases in the first month post-training, but was not observed five months later. |

|

[35] |

15 communities in a large metropolitan area USA |

Training program for managers of bars/restaurants designed to establish and promote RBS policies and practices |

RCT |

Pre-post survey |

Statistically significant increases in certain RBS practices were observed in both the treatment and control groups 6-months post-intervention. |

|

[41] |

Stockholm, Sweden |

Assess cost-effectiveness of the program (e.g., cost-savings in reduced assaults) |

Cost-savings analysis |

Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYS), surveys, costs |

The restaurant intervention aimed at reducing alcohol and drug problems resulted in societal cost-savings and led to health gains due to fewer assaults. |

|

[36] |

Education program administered in 8 states (Lafayette, LA; Washtenaw County, MI; York, PA; Houston, TX; Springfield, MA; Newark/Newcastle, DE; Clinton/ Muscatine/Bettendoff, IA; Everett/ Lynwood/Marysville, WA) USA |

Assess the effect of server-intervention education and the effect of various situational variables upon program effectiveness |

Pre-post design with comparison group |

Self-reported measures on knowledge, attitude and behavior (pre- to post-) |

While there were significant improvements in self-reported measures and observed interventions at program sites, there were state effects (e.g., positive changes occurred in five states). Additionally, cessation of alcohol service after the intervention was low. |

|

[24] |

Washtenaw County, MI, USA |

Assess the effectiveness of enforcing laws on overservice of alcohol to intoxicated patrons |

Pre-post design with comparison group |

Refusal of service to pseudo-patrons, drunk driving arrests |

Program sites were more likely to decline service to intoxicated patrons and there were fewer DWI arrests. |

|

[37] |

Enlistment club at a Naval base USA |

Effect of server intervention on consumption |

QED |

Observations of customer behavior, administrative data and interviews |

The number of intoxicated patrons decreased by nearly half. |

|

[38] |

States with dram shop, RBS training and state control alcohol laws USA |

Effects of MLDA-21 laws on reducing underage drinking and driving fatal crashes |

Structural equation modeling |

Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) |

RBS laws led to statistically significant reductions in beer consumption and fatal crash rates of underage. |

|

[26] |

Six studies evaluating multicomponent programs in the United States (California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas and Wisconsin) USA |

Effectiveness and economic efficiency of multicomponent programs (including RBS) with community mobilization for reducing alcohol-impaired driving |

Systematic review |

Alcohol related crashes (and proxies) |

With the exception of one program, all programs exhibited a decrease in alcohol-related crashes. |

|

[39] |

Five bars in a major metropolitan area USA |

Effectiveness of Project ARM |

Pre- and post-test |

Pseudo-intoxicated patrons, purchase attempts |

Sales to under-age consumers decreased by 11.5% and sales to pseudo-intoxicated patrons decreased by 46%. |

|

[40] |

Stockholm, Sweden (five papers) |

Effects of the community action program on alcohol consumption at licensed premises |

Systematic review |

Observations of alcohol sales to pseudo-intoxicated individuals, questionnaire, violent crime, public opinion |

Pre- and post-data from two studies showed a statistically significant reduction in alcohol sales to those observed to be intoxicated. Additionally, one time-series study showed a 29% reduction in violence. Another study showed that the public supported RBS training. |

|

[42] |

Stockholm, Sweden |

Public opinion on strategies to reduce alcohol service issues |

Public opinion |

Questionnaire (public opinion on RBS) |

Overall, there is support for RBS as a means to reduce intoxication. However, there was lower support from frequent alcohol consumers, men and people younger than 30. |

|

[41] |

Stockholm, Sweden |

Effects a community alcohol prevention program on alcohol service (includes RBS) |

Pre- and post-test |

Pseudo-intoxicated patrons |

In the post-test, 47% (statistically significant) of licensed premises denied service to pseudo-patrons. |

|

[43] |

Jyväskylä, Finland |

Effects of an alcohol prevention program (law enforcement, RBS, campaigns and policy initiatives) to reduce the serving of alcoholic beverages to intoxicated clients on licensed premises |

Controlled pre-post study |

Observations of pseudo-intoxicated individuals |

Statistically significant increase (19%) in alcohol sale refusals at treatment sites. |

|

[44] |

300 on-site alcohol-serving establishments in New Mexico, USA |

Effectiveness of the Way-To-Serve (WTS) RBS training |

RCT |

Pseudo-intoxicated patrons |

Sites that participated in the online WTS had higher rates of refusals in immediate follow-up, six-months and one-year, but only statistically significant immediately after and one-year after intervention. WTS sites were also more likely to refuse service to younger looking pseudo-intoxicated patrons. |

Table 2: Provides a summary of the 24 studies showing RBS to be effective.

RBS Not Effective

The following six studies could not find RBS training as effective in reducing the outcomes they analyzed. Table 3 summarizes the studies showing RBS not to be effective.

|

Authors/ Year |

Setting |

Focus |

Study Design |

Measures |

Findings |

|

[45] |

Licensed premises inside and outside football arenas in Stockholm (treatment) and Gothernurg (control) Sweden |

Alcohol intoxication and over-service at sporting events |

QED |

Mean BAC, proportion of spectators with high intoxication levels, overserving at licensed premises inside arenas, refused arena entry of obviously intoxicated spectators |

While improvements were observed with regards to refusal rates (sales and entry) and BAC levels, the improvements differed by site and were equivocal over time. |

|

[46] |

20 shebeens (10 licensed and 10 unlicensed) in Gugulethu, Cape Town South Africa |

Reduce alcohol-impaired road use |

Implementation |

Questionnaire, breathalyzer, observations of service to pseudo-intoxicated patrons |

Server practices improved, but BAC levels of patrons were not different from pre-post. |

|

[47] |

50 sporting clubs from two metropolitan and two regional areas in Victoria, Australia |

Determine the effectiveness of a sales monitoring intervention to reduce sales to youth and community awareness |

QED |

Pre-post purchase observations |

While both the treatment and comparison sites improved pre-post, there were no statistically significant increases in compliance or improvements in age verification. |

|

[48] |

Effectiveness of RBS in Norway based on three studies (Trondheim, Bergen and five communities that implemented RBS as part of a community action project) |

Reduce sales of alcohol to youth and to intoxicated individuals; Reduce alcohol-related violence |

Outcome (Trondheim and Bergen); QED (the community action project) |

Observations of service to pseudo-intoxicated and pseudo-underaged patrons in bars (Trondheim and Bergen); Observations of server responses in bars (Trondheim and Bergen); Surveys of youth (Trondheim and community action project); Police records of reported violence (Trondheim); Participating observations in projects groups etc. (Trondheim); Participating observations in training sessions etc. (Bergen); Document review (community action project) |

In Trondheim, there was an increase in overservice to pseudo-intoxicated patrons and pseudo-underaged patrons between 2004 and 2006. Additionally, there was no change in reported violent assaults. None of these results were statistically significant. In Bergen, there was an increase in overservice to pseudo-intoxicated patrons; statistically significant (p<.05). In the five communities, there was a small increase in violence in both the program and control communities, but it was greater in the control (i.e., 3% versus a 6% increase). |

|

[49] |

Licensed premises in New South Wales Australia |

Reduce overservice to intoxicated patrons |

Longitudinal (assessing whether there were changes between findings in 2002 and 2006) |

Telephone survey to determine if appropriate RBS initiatives were administered |

Findings showed that there was an increase in RBS initiatives from 2002 to 2006, those who reported to have been more intoxicated were still served alcohol (65% in 2002 and 54% in 2006). Although, this was not statistically significant. |

|

[50] |

SALUTT (replication of STAD program) in Oslo, Norway |

Reduce alcohol-related violence |

Outcome |

Pre-post analysis of geo-coded data on violence |

Oslo saw less success in this replication of STAD. There was no statistically significant effect on reducing violence. |

Table 3: Findings that RBS is Not Effective.

Discussion

According to the literature that was reviewed, the number of studies showing positive effects of RBS training and enforcement outweighed the studies that found no effect. More importantly, several of the studies showing positive effects had strong designs, methods and appropriate data analyses. However, the stronger studies also tended to include a multi-component approach involving alcohol harm reduction strategies in addition to RBS training. Examples include community mobilization, increased impaired driving enforcement (e.g., sobriety checkpoints) and zoning policies that limit alcohol availability [11].

The studies finding no RBS training effects discussed numerous barriers to implementation: e.g.,

- Lack of incentives for the servers;

- Lack of buy-in by the owners and managers;

- Turnover of serving staff;

- Lack of enforcement of alcohol laws (i.e., serving to obviously intoxicated patrons);

- The heavy episodic drinking culture of bar patrons;

- The implementation methods of the RBS training was weak, among other factors.

There are publications that provide guidance to practitioners who are interested in implementing an RBS program in their community. See Table 4 for a summary of these studies.

|

Authors/ Year |

Setting |

Focus |

Intervention |

Program Components |

Successes |

Challenges |

|

[41] |

92 Licensed premises in Stockholm, Sweden |

Reducing the over-service of intoxicated patrons |

STAD Project (Stockholm Prevents Alcohol and Drug Problems) |

RBS |

Some premises (five) refused further service to pseudo-intoxicated individuals. |

Bartenders and servers at 95% of observed licensed premises continued to serve actors acting as intoxicated patrons. |

|

[27] |

Alcohol outlets in 6 South Carolina counties USA |

Underage drinking prevention |

Underage drinking prevention |

RBS, enforcement of alcohol sales |

Merchants that have stronger beliefs in RBS training (i.e., state-approved trainings) and preventing sales to minors were more likely to check IDs. |

Data were self-reported and the study is not generalizable given that the sample was selected within one state. |

|

[35] |

Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area USA |

Service industry attitudes towards RBS and practices |

Enhanced Alcohol Risk Management (eARMTM) |

RBS |

2014 participants were more concerned with over-service, were more aware of written policies about RBS and had positive relationships with law enforcement and feared repercussions of underage sales. |

The 1999 and 2014 participants actually reported benefits to overserving patrons. |

|

[44] |

Licensed premises inside and outside football arenas in Stockholm (treatment) and Gothernurg (control) Sweden |

Alcohol intoxication and over-service at sporting events |

RBS |

Service denial |

Serving staff both inside and outside of the arenas paid more attention to signs of intoxication. |

Serving staff at licensed premises outside the arena were more likely to deny alcohol service than staff within the arena (66.9% compared to 24.9%). This suggests greater need to train serving staff in arenas, as well as staff that are at the arena entry, on identifying intoxicated individuals. |

|

[12] |

Three USA communities (located in Northern California, Southern California and South Carolina) |

Reduce alcohol-related injuries and death |

Preventing Alcohol Trauma: A Community Trial |

Community mobilization, RBS, law enforcement, underage drinking and zoning and municipal controls on alcohol access |

-- |

Reductions in alcohol-involved crashes and underage sales, as well as increases in RBS policies and regulations to reduce concentration of alcohol outlets were observed. |

|

[37] |

Review of various RBS studies |

Identify components for an RBS |

Multi-component RBS |

Trainings to address server behaviors, pseudo-intoxicated patrons |

There is support from businesses and servers for RBS training. |

There are various ways to measure RBS effectiveness, but changing behaviors and maintaining those changes is the most important component. |

|

[50] |

Australia |

Integrate and institutionalize RBS training |

Alcohol Accords |

Law enforcement |

RBS training could help reduce alcohol-related issues. |

Moving in this direction would require creating an environment that is receptive to RBS training. This includes obtaining support from the research community, police, businesses and local communities. |

|

[51] |

235 Swedish municipalities |

Implementation and promotion of RBS |

Multi-component RBS |

RBS training, development of a community-coalition steering group and supervision visits. |

The more promotion there is of a program, the higher the level of implementation. |

While all municipalities said they implemented to fidelity, only 13% implemented all three components of the RBS program |

|

[52] |

Bars and rum shops in St. Vincent and the Grenadines in the Caribbean |

Reduce heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related harms |

RBS (not standardized) |

Not discussed |

Shopkeepers and bartenders expressed concern with problem drinking and some reported making efforts to intervene. |

Attitudes towards problem drinking make it complicated for an intervention to be effective. However, there is no standard training, so mandated training may be more effective if promoted appropriately. |

|

[33] |

Seven Major League Baseball Facilities USA |

Reduce alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problem behavior |

Techniques for Effective Alcohol Management (TEAM) |

Assessment of current policies, development of new policies and procedures to prevent alcohol abuse, policy implementation and evaluation of implementation. |

Findings showed that stadium management and staff supported TEAM, it was easy to implement and staff felt that they had the tools needed to address issues. Data showed fewer alcohol sales during the study and spectators indicated that they drank less. |

Given that the evaluation was more exploratory, it is difficult to assess true effectiveness without an experimental or quasi-experimental study. |

Table 4: Studies Describing the Implementation of RBS Programs.

[53] published a guide that presents detailed descriptions of potentially effective approaches to preventing impaired driving by college students who abuse alcohol. Chapter 1 of the guide provides an overview of alcohol-impaired driving and discusses changes in public attitudes, the scope of the problem, involvement of teens and young adults and the challenge of reaching college students. Chapter 2, on increasing awareness, discusses typical awareness messages, national awareness programs ("Students Against Driving Drunk" and "Boost Alcohol Consciousness Concerning the Health of University Students" (BACCHUS)) and designing awareness messages for young adults. A chapter on alternative transportation programs reviews the designated driver program and safe ride programs. Next, a review of responsible beverage service programs includes the "Training for Intervention Procedures by Servers of Alcohol" (TIPS) program and the "Stanford Community Responsible Hospitality Project". Deterrence strategies to prevent alcohol-impaired driving are discussed in the fifth chapter and include use of sobriety checkpoints, controlling student access to alcohol and school-imposed penalties. The final chapter is a call for public action. Described RBS training programs evaluated by the NHTSA. The objectives of the RBS programs included raising awareness of alcohol-related driving problems, increasing willingness to prevent alcohol-impaired driving among alcohol outlet customers and friends [54], increasing the ability to prevent drunk driving and determining each program's effectiveness in preventing alcohol-impaired driving crashes. The RBS program consisted of six, one-hour instruction modules, with an optional seventh module designed for managers who need to instruct their employees in safe alcohol service. Servers were taught alcohol service strategies, which, if used properly, should not make termination of service to customers necessary. The modules discuss (a) the concept of server liability and its implications in a commercial establishment, (b) the moral and legal responsibility to prevent drunk driving, (c) methods to control consumption and reduce the levels of impairment and (d) ways of intervening with intoxicated customers. The training includes managers participating in roleplay exercises to test their intervention skills and refine their strategies. Managers are also encouraged to work out policies to use in their facilities.

Discusses how off-premises outlets (e.g., liquor and convenience stores) and on-premises outlets (e.g., bars and restaurants) are alike and different [55]. The authors conducted a survey of managerial or supervisory staff and/or owners of 336 off- and on-premises alcohol outlets in six counties in South Carolina, comparing these two outlet types on their preferences regarding certain alcohol sales practices, beliefs toward underage drinking, alcohol sales practices and outcomes. Multilevel logistic regression showed that while off- and on-premises outlets did have many similarities, off-premises outlets appear to engage in more practices designed to prevent sales of alcohol to minors than on-premises outlets. The relationship between certain RBS practices and outcomes varied by outlet type [56-59]. This study furthers the understanding of the differences between off- and on-premises alcohol sales outlets and offers options for increasing and tailoring environmental prevention efforts to specific settings.

Conclusion

In summary, there are strong indications that RBS training, when implemented correctly, when sustained and when owners and managers buy into the strategy, can substantially reduce harms due to risky alcohol consumption. Numerous barriers must be overcome, but there are strategies that can deal with the obstacles. Buy-in by the bar managers and owners, incentives for the servers to practice RBS, refresher training, enforcement of the alcohol policies and a multi-component approach to reduce alcohol harm appear to be staples for a successful RBS training program.

Despite the limitation of this review covering literature from other languages other than English, the evidence presented in this review is instructive to different stakeholders involved in the design and implementation of RBS as a strategy to tackle alcohol related harms in communities around the world. The review also provides a basis for further research into the topic, particularly on how to improve the effectiveness of RBS training programs and hence avoid the trap of deployment of wasteful and ineffective programs.

Acknowledgement

This review was funded by the AB InBev Foundation (ABIF), New York, NY, USA. The results and conclusions are those of the authors with no ABIF influence to change, add or delete any finding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

References

- Poznyak V and Dekve D (2018a) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018.(WHO) ISBN: 978-92-4-156563-9, Geneva.

- Brennan I, Moore SC, Byrne E, Murphy S (2011) Interventions for disorder and severe intoxication in and around licensed premises, 1989-2009. Addiction 106: 706-713.

- WHO (2018b) Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018. ISBN: 978-92-4-156568. Geneva.

- Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA, Nichols JL, Alao MO, et al. (2001) Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol impaired driving. Am J Prev Med 2: 66-88.

- Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL (2002) Effects of minimum drinking age laws: Review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000. J Stud Alcohol: 206-225.

- Fell JC, Scherer M, Thomas S, Voas RB (2016) Assessing the impact of twenty underage drinking laws. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 77: 249-260.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (2023) Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- Bhullar D (2012) Drunken driving: Indian perspective in world scenario and the solution. J of Punjab Academy of Forensic Med Toxicol 12: 5-9.

- Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Blincoe L (2013) Costs of alcohol-involved crashes, United States, 2010. Ann Adv Automot Med 57: 3-12.

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis (2021) Alcohol impaired driving: 2019 data (Traffic Safety Facts. Report No. DOT HS 813 120). NHTSA.

- Holder HD, Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, Treno AJ, Grube JW, et al. (2000) Effect of community-based interventions on high-risk drinking and alcohol-related injuries. JAMA 284: 2341-2347.

- Holder HD, Saltz RF, Grube JW, Voas RB, Gruenewald PJ, et al. (1997) A community prevention trial to reduce alcohol-involved accidental injury and death: overview. Addiction 92: S155–S171.

- Zador PL, Krawchuk SA, Voas RB (2000) Alcohol-related relative risk of driver fatalities and driver involvement in fatal crashes in relation to driver age and gender: An update using 1996 data. J Stud Alcohol 61: 387-395.

- Liu S, Siegel PZ, Brewer RD, Mokdad AH, Sleet DA, et al. (1997) Prevalence of alcohol-impaired driving. Results from a national self-reported survey of health behaviors JAMA 277: 122-125.

- Foss RD, Perrine MW, Meyers AM, Musty RE, Voas RB (1990) A roadside survey in the computer age. In M.W. Perrine (Ed.), Proceedings of the 11thinternational conference on alcohol, drugs and traffic safety, October 24-27, 1989, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Chicago: N Safety Council 920-929.

- Eby DW (1995) The convicted drunk driver in Michigan: a profile of offenders. UMTRI Res Rev 25: 5.

- Anglin L, Caverson R, Fennel R, Giesbrecht N, Mann RE (1997) A study of impaired drivers stopped by police in Sudbury, Ontario. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation.

- Lacey JH, Kelley-Baker T, Furr-Holden D, Voas RB, Moore C, et al. (2009) 2007 National roadside survey of alcohol and drug use by drivers: Methodology. (Report No. DOT HS 811 237). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- Fell JC, Tippetts S, Voas R (2010) Drinking characteristics of drivers arrested for driving while intoxicated in two police jurisdictions. Traffic Inj Prev 11: 443-452.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (2016) Digest of impaired driving and selected beverage control laws, 29th edition. (Report No. DOT HS 812 267). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- Mosher JF (1983) Server intervention: A new approach for preventing drinking-driving. Accid Anal Prev, 15: 483-497.

- Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL (2006) Alcohol Sales and Service to Underage Youth and Intoxicated Patrons: Effects of Responsible Beverage Service Training and Enforcement. Traffic Safety and Alcohol Regulation A Symposium June 5–6, 2006 Irvine, California.

- Jones L, Hughes K, Atkinson AM, Bellis MA (2011) Reducing harm in drinking environments: A systematic review of effective approaches. Health Place 17: 508- 518.

- McKnight AJ, Streff FM (1994) The effect of enforcement upon service of alcohol to intoxicated patrons of bars and restaurants. Accid Anal Prev 26: 79-88.

- Fell JC, Fisher DA, Yao J, McKnight AS, Blackman KO, et al. (2017) Evaluation of responsible beverage service to reduce impaired driving by 21- to 34-year-old drivers (Report No. DOT HS 812 398). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- Shults R, Elder R, Nichols J, Sleet D, Compton R, et al. (2009) Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Effectiveness of multicomponent programs with community mobilization for reducing alcohol-impaired driving. Am J Prev Med 37: 360-371.

- Chinman M, Ebener P, Burkhart Q, Osilla KC, Imm P, et al. (2014) Evaluating the Impact of Getting to Outcomes-Underage Drinking on Prevention Capacity and Alcohol Merchant Attitudes and Selling Behaviors. Prev Sci 15: 485-496.

- Fell JC, Tanenbaum E, Chelluri D (2018) Evaluation of a combination of community initiatives to reduce driving while intoxicated and other alcohol-related harms. Traffic Inj Prev 19: S176–S179.

- George MD, Bodiford A, Humphries C, Stoneburner KA, Holder HD (2018) Media and Education Effect on Impaired Driving Associated With Alcohol Service. J Drug Educ 48: 86-102.

- Graham K, Osgood DW, Zibrowski E, Purcell J, Gilksman L, et al. (2004) The effect of the Safer Bars programme on physical aggression in bars: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Rev 23: 31-41.

- Grube JW, De Jong W, De Jong M, Lipperman-Kreda S, Krevor BS (2018) Effects of a responsible retailing mystery shop intervention on age verification by servers and clerks in alcohol outlets: A cluster andomized cross-over trial. Drug Alcohol Rev 37: 774–781.

- Holder HD, Wagenaar AC (1994) Mandated server training and reduced alcohol- involved traffic crashes: A time series analysis of the Oregon experience. Accid Anal Prev 26: 89-98.

- Howard-Pitney B, Johnson MD, Altman DG, Hopkins R, Hammond N (1991) Responsible alcohol service: A study of server, manager and environmental impact. Am J Public Health 81: 197-198.

- Johnsson KO, Berglund M (2003) Education of key personnel in student pubs leads to a decrease in alcohol consumption among the patrons: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction 98: 627-633.

- Lenk KM, Erickson DJ, Nelson TF, Horvath KJ, Nederhoff DM, et al. (2018) Changes in alcohol policies and practices in bars and restaurants after completion of manager-focused responsible service training. Drug Alcohol Rev 37: 356-364.

- McKnight AJ (1991) Factors influencing the effectiveness of server-intervention education. J Stud Alcohol 52: 389-397.

- Saltz RF (1987) The roles of bars and restaurants in preventing alcohol-impaired driving: An evaluation of server intervention. Evaluation and the Health Professions 10: 5-27.

- Scherer M, Fell JC, Thomas S, Voas RB (2015) Effects of Dram Shop, Responsible Beverage Service Training and State Alcohol Control Laws on Underage Drinking Driver Fatal Crash Ratios. Traffic Inj Prev 16: S59-S65.

- Toomey TL, Wagenaar AC, Gehan JP, Kilian G, Murray DB, et al. (2001) Project Arm: Alcohol risk management to prevent sales to underage and intoxicated patrons. Health Educ Behav 28: 186-199.

- Wallin E (2004) Responsible beverage service?: Effects of a community action project Department of Public Health Sciences.

- Wallin E, Gripenberg J, Andreasson S (2002) Too drunk for a beer? A study of overserving in Stockholm. Addiction 97: 901-907.

- Wallin E, Gripenberg J, Andréasson S (2005) Overserving at licensed premises in Stockholm: effects of a community action program. J Stud Alcohol 66: 806-814.

- Warpenius K, Holmila M, Mustonen H (2010) Effects of a community intervention to reduce the serving of alcohol to intoxicated patrons. Addiction 105: 1032-1040.

- Woodall WG, Starling R, Saltz RF, Buller DB, Stanghetta P (2018) Results of a randomized trial of web-based retail onsite responsible beverage service training: WayToServe. J Stud Alcohol Drug 79: 672–679.

- Elgán TH, Durbeej N, Holder HD, Gripenberg J (2021) Effects of a multi-component alcohol prevention intervention at sporting events: a quasi-experimental control group study. Addiction 116: 2663-2672.

- Peltzer K, Ramlagan S, Gliksman L (2006) Responsible Alcoholic Beverages Sales and Services Training Intervention in Cape Town: A Pilot Study. J Psychol Africa 16: 45-52.

- Kremer P, Crooks N, Rowland B, Hall J, Toumbourou JW (2021) Increasing compliance with alcohol service laws in community sporting clubs in Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev 41: 188-196.

- Rossow I, Baklien B (2010) Effectiveness of Responsible Beverage Service: The Norwegian Experiences. Contemporary Drug Problems 37: 91-108.

- Scott L, Donnelly N, Poynton S, Weatherburn D (2007) Young adults’ experience of responsible service practice in NSW: an update. Alcohol Studies Bulletin 9: 1-8.

- Skardhamar T, Fekjær SB, Pedersen W (2016) If it works there, will it work here?.The effect of a multi-component responsible beverage service (RBS) programme on violence in Oslo. Drug Alcohol Depend 169: 128-133.

- Stockwell T (2001) Responsible alcohol service: lessons from evaluations of server training and policing initiatives. Drug Alcohol Rev 20: 257–265.

- Trolldal B, Haggård U, Guldbrandsson K (2013) Factors associated with implementation of a multicomponent responsible beverage service program – Results from two surveys in 290 Swedish municipalities. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 8: 1-10.

- Zafer M, Liu S, Katz CL (2018) Bartenders’ and Rum Shopkeepers’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward “Problem Drinking” in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Psychiatric Quarterly, 89: 801-815.

- DeJong W (1996) Preventing Alcohol-Related Problems on Campus: Impaired Driving. A Guide for Program Coordinators.

- Vegega ME (1986) NHTSA Responsible Beverage Service Research and Evaluation Project. Alcohol Health Research World 10: 20-23.

- Chinman M, Burkhart Q, Ebener P, Fan CC, Imm P, et al. (2011) The premises is the premise: understanding off- and on-premises alcohol sales outlets to improve environmental alcohol prevention strategies. Prev Sci 12: 181-191.

- Kennedy BP, Isaac NE, Nelson TF, Graham JD (1997) Young male drinkers and impaired driving intervention: Results of a U.S. telephone survey. Accid Anal Prev 29: 707-713.

- Nelson TF, Kennedy BP, Isaac NE, Graham JD (1998) Correlates of drinking-driving in men at risk for impaired driving crashes. American Journal of Health Behavior 22: 151-158.

- Stockwell T, Lang E, Rydon P (1993) High risk drinking settings: The association of serving and promotional practices with harmful drinking. Addiction 88: 1519-1526.

- Grube JW (1997) Preventing sales of alcohol to minors: results from a community trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 92: 251-260.

Citation: Fell JC, Scolese J, Achoki T (2024) The Effectiveness of Responsible Beverage Service Training Programs: A Literature Review and Synthesis. J Alcohol Drug Depend Subst Abus 10: 036.

Copyright: © 2024 James C Fell, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.