The Role of Trauma CT in Suspected Intra-Abdominal Injury - A Case Report

*Corresponding Author(s):

Emma MullenDepartment Of Obstetrics And Gynecology, University Hospital Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

Tel:07772151404,

Email:e.e.mullen@icloud.com

Abstract

Despite Computerised Tomography (CT) becoming the standard primary investigation when managing severe trauma, most clinical guidelines do not recommend it in haemodynamically unstable patients. The inherent time delay and clinical setting associated with the investigation has warranted it the nickname of “tunnel of death”.

Although traditionally the risks have outweighed the benefits with performing a CT scan, as hospital infrastructure improves, this balance is changing. With an increasingly 24 hour service; including radiologists, surgeons of varying specialties and critical care, the support for the trauma patient is improving. In addition, the speed and quality of the scans allows for accurate diagnoses when guiding definitive management, instead of the standard explorative surgery.

The published research is minimal, with no risk stratification tool currently available when initially assessing the risks and benefits of a CT scan.

We report a case of a 47 year old female whose outcome was improved through detailed assessment of her injury and anatomy using a trauma CT series. This was in the clinical presentation of catastrophic haemorrhage and instability. By visualising her collateral blood supply, a transected common hepatic artery was able to be tied off with some confidence that retrograde flow would be suffcient to preserve liver function compatible with life.

Keywords

Blunt-traumatic injury; CT scan; Hypoxic liver injury

ABBREVIATIONS

GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale

ICD: Intercostal Drain

CT: Computerised Tomography

GICU: General Intensive Care Unit

NAC: N-acetylcholine

ALT: Alanine Transaminase

ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase

NICE: National Institute of Clinical Excellence

INTRODUCTION

Although many blunt trauma patients receive a CT series upon admission to hospital; for those who are haemodynamically unstable, it is not routinely advised. Of relevance within the NHS, it is not currently recommended by NICE or ATLS guidelines.

A trauma series may, however, be indicated to identify a source of haemorrhage and assess the surrounding anatomy. The situation is dealt with on a case-by-case basis and strongly reflects both the experience and preference of the managing clinician.

The CT scanner has been referred to as the “tunnel of death” for the unstable patient. This reflects the associated time and setting of the investigation. It has not been routinely advised, as the risk of delaying definitive treatment is too significant [1]. By transporting a patient to an area with reduced clinical support and monitoring, the potential benefit of accurate diagnosis is under question.

Currently, there is no consistent evidence about the effect on outcome of CT scans in unstable patients. One large-scale observational study showed that whole body CT scan was beneficial in this cohort [2]. However, a second study found CT had a negative impact in pre-operative abdominal trauma patients [3].

A large retrospective cohort study in Japan of nearly 6000 patients found no detrimental effect of undertaking a CT scan in unstable trauma patients. This held true even when adjusted for confounding factors. The conclusion of this paper was that current guidelines were not to be supported and supported the use of diagnostic CT in this patient cohort [1].

Other studies have found no significant association between mortality and imaging. The lack of consensus may reflect the difference in the set up of the study or that of the healthcare system being investigated [1,4].

Our case study exemplifies why guidelines need to be considered in relation to each specific case in question. Although it is acknowledged that their is a place for CT scanning in trauma, the recommendations are non-specific and become ever-outdated as our services advance.

NICE guidelines state that imaging for haemorrhage should be performed urgently and interpreted immediately by an appropriately qualified clinician. The next note places a limitation on imaging in those patients who are hypotensive and non-responsive to resuscitation [5].

Immediate CT is only to be “consider[ed]” in patients with suspected haemorrhage that respond to resuscitation or in those with a normal blood pressure. This mirrors the international guidelines that consider haemodynamic instability a relative contraindication to performing a CT scan.

NICE recommendations state that patients at risk of arrest from haemodynamic instability should be taken straight for damage control surgery, with a diagnostic laparotomy being favoured to identify and subsequently treat the site of haemorrhage.

With ever-improving imaging modalities and staff training, the relative contraindications to a trauma CT series become less significant. The time taken to perform these scans is continuing to reduce, therefore placing the patient at a reduced risk relating to the timescale and setting of the investigation. As hospitals within the NHS move towards a 24 hour service, it is also more likely for an appropriate reporting clinician to be present. Particularly in trauma centres, radiologists are often now available to attend the CT scan themselves and provide an immediate preliminary report.

CASE STUDY

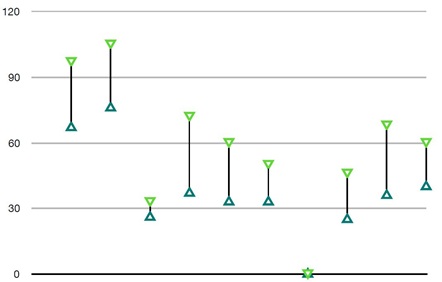

This case relates to a 47 year old female with a background of psychotic depression with a superimposed acute delirium. They suffered a witnessed fall from a 4th story window leading to a life-threatening poly-trauma. At the time of the arrival of the emergency services, the patient had a GCS of 6, was pale, cold and cyanosed. Their capillary refill was greater than 5 seconds with an undetectable radial pulse and a fluctuating blood pressure ranging from 105mmHg systolic down to 33mmHg (Graph 1). The patient was found to have a tension pneumothorax, for which they underwent a roadside thoracostomy, de-compression of the pneumothorax and insertion of an ICD. They were intubated with a rapid induction for poor respiratory effort.

The patient was transferred to hospital as a haemodynamically unstable polytrauma. At arrival to ED the patient’s GCS was now 4, with a blood pressure ranging from undetectable to 72/37mmHg that was unresponsive to fluid resuscitation (Graph 1). They had an acute lactic acidosis and anaemia suggesting a likely internal haemorrhage. Despite this clinical presentation, the decision was made to scan the patient in order to identify a presumed occult internal bleed.

Graph 1: Blood Pressure values during the ambulance transfer and initial assessment in Resus, prior to CT scan.

Graph 1: Blood Pressure values during the ambulance transfer and initial assessment in Resus, prior to CT scan.

An immediate consultant radiologist report listed: multiple traumatic injuries, including a flail chest with residual haemathorax, bilateral sacral, pubic rami and right lumbar transverse process fractures and further fractures to the left radius and right scapula. There was also found to be a large active haemorrhage relating to a partial or complete transection of the common hepatic artery.

The patient was immediately taken for an emergency laparotomy and the difficult decision was made to tie o? the common hepatic artery at the coeliac trunk. It was hoped that the collateral blood supply identified through the CT scan would be suffient to support liver function going forward. Large bore drains were left in-situ to monitor any continued bleeding and relieve the pressure of the existing haemoperitoneum.

The day following the initial surgery a CT angiogram study of the mesenteric artery showed “patchy” areas of hypo-perfusion throughout the right liver lobe. A pseudoaneurysm had formed around the common hepatic artery stump, approximately 1cm distal to the origin of the left gastric artery. The splenic artery was not continuous with the coeliac trunk, yet remained perfused proximally, likely due to retrograde filling via the pancreatica magna. Despite truncation of the common hepatic artery, its distal portion, the proper hepatic, the cystic and the left and right hepatic arteries maintained perfusion. This was put down again to retrograde flow, this time from the gasproduodenal artery via the superior mesenteric artery.

The pre-, intra- and post-operative blood tests shown reflect the resuscitative measures in the acute setting (Table 1). This included administration of multiple transfusions of packed red blood cells, platelets, cryoprecipitate and fresh frozen plasma. Alongside this, repeat transexamic acid doses were given to minimise active haemorrhage.

|

Day 0 (Pre-operative) |

Day 0 (Intra-operative) |

Day 0 (Post-operative) |

|

|

Hb |

112 |

120 |

125 |

|

Plt |

146 |

82 |

125 |

|

CRP |

1 |

2 |

|

|

WCC |

16.5 |

10.6 |

8.7 |

|

INR |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

|

Total Protein |

51 |

42 |

51 |

|

Albumin |

29 |

24 |

29 |

|

Bilirubin |

21 |

15 |

19 |

|

ALT |

570 |

401 |

804 |

|

ALP |

58 |

48 |

54 |

|

eGFR |

40 |

35 |

32 |

|

Creatine Kinase |

3760 |

||

|

Phosphate |

3.33 |

3.24 |

|

|

Lactate |

10.7 |

11.6 |

Table 1: Blood results from the day of the trauma. Pre-, Intra- and Post-operative values are provided. During this period the patient received 8 unit’s red blood cells, 4 units of platelets, 18 fresh frozen plasma units and 4 of cryoprecipitate. This was alongside multiple fluid resuscitation boluses.

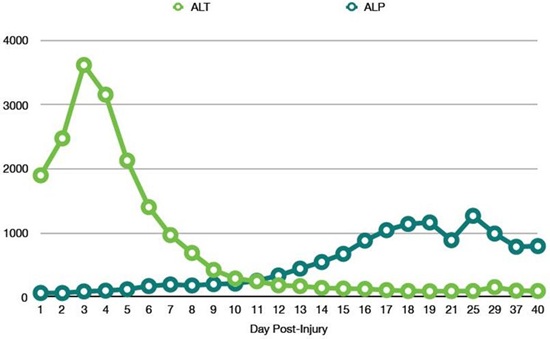

Initial hypoxic liver injury reflected by acute deterioration in liver function tests and the INR increase. At this time an IVC filter was placed in view of the contraindications for thromboprophylaxis. The ALP increase relates to both the hepatic trauma and the multiple fractures with on-going orthopaedic interventions.

Renal function was at its lowest with the trauma, indicating a likely hypovolaemic, pre-renal cause. Creatine kinase peaked following the traumatic injuries and improved with time and fluid resuscitation.

The full blood count results again reflect the acute injury and haemorrhage. The fluctuations are likely related to on-going transfusions within the first few days and subsequent operations.

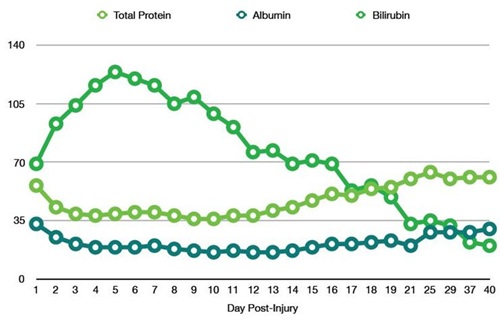

Of interest, inorganic phosphate is implicated in hepatic regeneration and is seen here to fall dramatically as the liver function tests improve. This was replaced IV, mirroring the changes seen.

Daily blood tests revealed an extensive developing liver injury in-keeping with the multiple areas of hypoperfusion seen on CT (Table 2, Graph 2,3). The patient required post-operative NAC infusions and was placed on the hepatic encephalopathy bowel protocol for hepatic protection.

|

Day |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

21 |

25 |

29 |

37 |

40 |

|

Hb |

112 |

91 |

83 |

78 |

74 |

78 |

75 |

76 |

91 |

82 |

81 |

78 |

89 |

91 |

94 |

101 |

93 |

99 |

104 |

109 |

121 |

133 |

133 |

135 |

|

Plt |

79 |

54 |

70 |

68 |

57 |

72 |

102 |

118 |

133 |

166 |

202 |

230 |

309 |

323 |

379 |

398 |

364 |

307 |

352 |

129 |

242 |

218 |

238 |

202 |

|

CRP |

15 |

94 |

134 |

129 |

93 |

48 |

25 |

22 |

51 |

92 |

76 |

48 |

35 |

21 |

18 |

18 |

12 |

12 |

8 |

6 |

4 |

8 |

|

5 |

|

WCC |

7.8 |

8.6 |

9.1 |

8.3 |

5.4 |

10.4 |

12.6 |

11.7 |

13.5 |

13 |

10.1 |

8.4 |

9.2 |

8.4 |

10 |

9.9 |

6.4 |

8.1 |

8 |

6.9 |

6.1 |

7.4 |

6.1 |

8 |

|

INR |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.4 |

|

1.3 |

|

|

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

1.2 |

1.1 |

|

|

|

1.1 |

1.1 |

1 |

1.1 |

|

TP |

56 |

43 |

39 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

40 |

38 |

36 |

36 |

38 |

38 |

41 |

43 |

47 |

51 |

50 |

54 |

55 |

|

64 |

60 |

61 |

61 |

|

Alb |

33 |

25 |

21 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

20 |

18 |

17 |

16 |

17 |

16 |

16 |

17 |

19 |

21 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

20 |

28 |

28 |

28 |

30 |

|

Bili |

69 |

93 |

104 |

116 |

124 |

120 |

116 |

105 |

109 |

99 |

91 |

76 |

77 |

69 |

71 |

69 |

53 |

56 |

49 |

33 |

35 |

32 |

22 |

20 |

|

ALT |

1899 |

2474 |

3616 |

3155 |

2129 |

1404 |

969 |

690 |

426 |

292 |

250 |

186 |

174 |

146 |

136 |

130 |

112 |

98 |

94 |

|

97 |

158 |

103 |

98 |

|

ALP |

67 |

66 |

91 |

103 |

124 |

174 |

199 |

184 |

204 |

213 |

257 |

339 |

446 |

549 |

676 |

882 |

1045 |

1141 |

1165 |

889 |

1268 |

992 |

786 |

797 |

|

eGFR |

|

39 |

|

|

|

68 |

|

|

|

|

|

79 |

|

>90 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CK |

10091 |

13209 |

|

|

2464 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PO4 |

1.75 |

|

0.77 |

0.68 |

0.59 |

0.41 |

0.85 |

|

|

0.74 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2: Blood results during admission.

Graph 2: Representation of the trend for Alkaline Phosphatase and Alanine Transferase. The ALT peaks relating to the acute hypoxic liver injury. The ALP results reflect the liver trauma and on-going fractures with orthopaedic interventions.

Graph 2: Representation of the trend for Alkaline Phosphatase and Alanine Transferase. The ALT peaks relating to the acute hypoxic liver injury. The ALP results reflect the liver trauma and on-going fractures with orthopaedic interventions.

Graph 3: Representation of the trend for Blood Protein and Bilirubin. The recovery of albumin reflects the resolving liver injury and recovery of synthetic function. The peak and fall of Bilirubin again mirrors the hepatic trauma.

Graph 3: Representation of the trend for Blood Protein and Bilirubin. The recovery of albumin reflects the resolving liver injury and recovery of synthetic function. The peak and fall of Bilirubin again mirrors the hepatic trauma.

Despite this, bloods worsened and the case was discussed with King’s College London Liver Transplant Team. They felt that the patient was for best supportive management and on-going monitoring, but would remain in contact if needed.

Follow-up CT liver triple phase showed a continuing, but stable, hypoxic liver injury and confirmed the initial assessment of retrograde flow supplying both the right and left hepatic arteries. With supportive management, blood tests showed improving liver function.

Subsequently, the patient underwent multiple orthopaedic procedures for her bony injuries, which are likely to reflect the continued rise in ALP (Table 2, Graph 2,3).

The patient remained at risk of complications including bile leak, liver necrosis and sepsis. Despite this, conservative management, with antibiotic and anti-fungal cover alongside multi-organ support, was su?cient for the patient to show significant improvement both clinically and biochemically.

Three weeks after the initial injury a further CT liver triple phase examination was performed. There was found to be improvement in the areas of hypoperfusion, with only a few linear areas of low attenuation in segments 5 and 6, and resolution of the pseudo-aneurysm.

This final view of the vasculature confirmed the coeliac trunk had been tied at its trifurcation, with continuous filling of the left gastric artery. The splenic artery was filling through retrograde flow and the hepatic arteries via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade and gastroduodenal artery.

Blood tests continued to improve, including those representative of the liver’s synthetic function. The patient remained of GICU for a total of 17 days, after which time she was transferred to an orthopaedic surgical ward.

After a further 23 days of surgical interventions for the multiple fractures, the patient had stabilised su?ciently to be transferred to a more local hospital.

CONCLUSION

This case represents a situation in which under standard protocols a CT scan would not have been performed initially. A CT trauma series is not recommended for patients who are haemodynamically unstable, with the scanner often being referred to as the “tunnel of death” for this patient cohort. A CT scan is contraindicated due to the risks of transporting the patients compromising their clinical condition, the di?culties with resuscitation while in the scanner and the potential delay in definitive treatment associated with acquiring images [1].

Previous studies have not only been few in number but have shown no general consensus regarding the effects of scanning patients on long term mortality [2,3].

Our patient under guidelines would have gone straight to theatre for explorative surgery, but the decision was made to scan them in order to identify the injury and direct surgical management. CT enabled the site of haemorrhage to be visualised and therefore a surgical plan to be made prior to opening the patient up. Imaging also allowed for the anatomy of the vasculature surrounding the injury to be seen. This further detail increased the confidence with which the transection injury could be tied off; leaving the patient reliant on a collateral supply that had already been interrogated radiologically.

This patient was extremely unstable with multiple reasons to not have any delay to definitive treatment. It would have been an easier decision to proceed straight to surgery given this is routine practice. The patient was able to be managed more appropriately and with an arguably more successful outcome due to deviation from guidelines.

This case exemplifies why recommendations should be questioned on an individual case basis. It also shows how more interrogation into these guidelines is needed.

The NICE guideline referred to in this case was published in 2016, which although relatively recently, is based on minimal up-to-date research or publications. Given the small number of studies with inconclusive and variable outcomes it is reasonable to suggest that further investigation is required.

Retrospective studies looking into the outcomes of trauma patients admitted relating their initial stability, imaging modality, management and overall outcomes would prove insightful to elaborate and reinforce current guidelines. This is particularly relevant as our services and skills improve changing the perceived risks of scanning vs operating.

In addition, case-based publications regarding the investigation and management of these trauma patients will provide clinicians with more confidence when deviating from guidelines.

Going forward, further retrospective studies with specific stratifications of patient cohort, for example the pre-morbid state of the patient or the mode of injury, will be useful to provide more detail to the guidelines.

REFERENCES

- Tsutsumi Y, Fukuma S, Tsuchiya A, Ikenoue T, Yamamoto Y, et al. (2017) Computed tomography during initial management and mortality among hemodynamically unstable blunt trauma patients: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 25: 74.

- Huber-Wagner S, Biberthaler P, Haeberle S, Wierer M, Dobritz M, et al. (2013) Whole-Body CT in haemodynamically unstable severely injured patients - a retrospective, multicentre study. Plos One 8: 10.

- Cook MR, Holcomb JB, Rahbar MH, Fox EE, Alarcon LH, et al. (2015) An abdominal computed tomography may be safe in selected hypotensive trauma patients with positive Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma examination. American Journal of Surgery 209: 834-840.

- Ordoñez CA, Herrera-Escobar JP, Parra MW, Rodriguez-Ossa PA, Mejia DA, et al. (2016) Computed tomography in hemodynamically unstable severely injured blunt and penetrating trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 80: 597-602.

- NICE Guidelines (2016) Major trauma: assessment and initial management [NG39]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London, UK.

Citation: Mullen E, Takhar A (2019) The Role of Trauma CT in Suspected Intra-Abdominal Injury - a Case Report. J Surg Curr Trend Innov 3: 020.

Copyright: © 2019 Emma Mullen, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.