Journal of Physical Medicine Rehabilitation & Disabilities Category: Medical

Type: Research Article

The Voluntary Practice of Eugenics: Risk-Taking and Religiosity as Determinants of Attitudes Toward Conceiving Children with Potential Genetic Disorders and Inheritable Diseases

*Corresponding Author(s):

Roy K ChenSchool Of Rehabilitation Services And Counseling, University Of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Texas, United States

Tel:+1 9566653590,

Email:roy.chen@utrgv.edu

Received Date: Apr 02, 2017

Accepted Date: May 12, 2017

Published Date: May 19, 2017

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine attitudes toward the voluntary practice of eugenics among people with high-risk inheritable diseases and genetic disorders. Participants consisted of 426 students attending two large public universities in the south and southwestern regions of the United States. The study used the modified scale of attitudes toward mental retardation and eugenics, the risk-taking questionnaire, and the dimensions of religious ideology importance scale. A general linear model was tested to answer the research question. The results showed that the model was significant (p < 0.001; adjusted r2 of 0.078). Significant main effects were found in race [F (4,378) = 2.538, p = 0.04, η² = 0.026], risk avoidance [F (1,378) = 12.536, p < 0.001, η² = 0.032] and importance of religion [F (1,378) = 5.530, p = 0.019, η² = 0.014]. Cultural, ethnic, and religious variables influenced people’s views toward disability. One’s perception of both disability and its impact on quality of life will influence his or her feelings about eugenics and babies with congenital conditions.

Keywords

Attitudes; Eugenics; Genetic disorders; Inheritable diseases; Religiosity, Risk-taking

INTRODUCTION

Globally, there are approximately 650 million people with disabilities [1]. The United States Census estimates that there are as many as 56.7 million Americans living with some form of disability [2]. Progress in social policy and legislative mandates have markedly improved the representation of people with disabilities in today’s diverse society; however, one major impediment to this progress remains the negative attitude and perception of non - disabled people toward their disabled counterparts [3]. In a study conducted in Australia, researchers found that age, educational attainment, and prior knowledge all impact attitudes and perceptions toward people with disabilities [4]. Specifically, people who are young, people who have higher educational attainment, and people who have had prior experience with intellectual disabilities are more likely to support the integration, inclusion, and acceptance of people with disabilities and less likely to endorse the ideology of eugenics. Society often conveys the message that impairment equals disability and that disability is abnormal and should be avoided [5]. However, degrading and labeling people with disabilities as worthless, damages not only these individuals, but also society as a whole [6]. Presently, disabilities, not individuals, are used to elicit sympathy or measurements of personal achievement, further illustrating that the acceptance of individuals with disabilities is never complete [7].

EUGENICS

The term eugenics, the study of human heredity, was first coined by Sir Francis Galton [8]. Eugenicists believe that genetics are the major contributors to the proclivity of such pathological traits as criminality, alcoholism, pauperism, mental health disorders and intellectual disabilities [8,9]. The concept of genetically predetermined conditions spreads rapidly through the educational and health professional fields and later dispersed into the general population. The pursuit of a perfect human race free of physically and intellectually sub-standard people began gaining traction in the early 20th century [9]. This newly popular belief, however, inadvertently led to the formulation of morally objectionable public policies that resulted in involuntary sterilizations, institutionalizations, and prohibitions of marriages among individuals with intellectual and psychological disabilities [8,10]. As newly passed eugenics laws took effect in 30 states, more than 60,000 Americans with psychological or intellectual disabilities or alternate sexual orientations suffered involuntary sterilizations and in some cases, were institutionalized [9]. Moreover, physicians were encouraged to euthanize infants with disabilities and terminate the gestation of defective fetuses [10]. On a macro level, the influence of eugenics on the national immigration policies and the drive to maintain a premium society was clearest in the imposition of far more rigorous requirements on Southern European immigrants, who were then generally thought to be intellectually inferior to their Anglo Saxon counterparts [5,9]. Today, rapid advancements in medical eugenics projects and genetic engineering have produced a business market in which prospective parents are able to select the sex, athletic ability, eye color and other preferred traits of their future offspring. The competing views on the philosophy of parental free choice and rights to a life absent of normality are certainly not to be taken lightly.

Religion and disability

Many Americans consider religion to be an essential part of their daily lives [11]. About 70.6% of Americans self - identified as Christians, 5.9% as members of non - christian faiths (e.g., Islam, Buddhism) and 3.1% as atheists [12,13]. The use of religion as a coping mechanism allows individuals to confront difficult situations by making sense of them and allocating emotional responses to aid in coping and adjustment [14]. Individuals living with disabilities or chronic illness face a variety of taxing and overwhelming challenges [6,14]. The ways in which these challenges are handled and overcome depend on the individuals involved. Coping mechanisms are the primary skills utilized to stand firm against disparaging incidents, such as discriminatory language and stereotyping. Religion has been deemed an important construct in assisting the coping process for many people facing infirmity and affliction [14]. As a result, professionals have become progressively interested in the religion, health, and the quality of life of diverse populations, especially individuals with chronic disabilities [15,16]. For example, Ellison [17] affirmed that a connection with God can produce a level of comfort and a pragmatic awareness of one’s purpose and quality of life.

Religion can help individuals with disabilities cope, find meaning in their newly constructed reality, achieve contentment and create new goals [15,16,18]. Pragament and Brant [19] showed that religion can produce either successful or unsuccessful mechanisms of coping, depending on the situation and the individual. For instance, one individual may use religion as a source of strength in order to cope with a situation, while another may have negative perceptions of religion as a result of unfavorable experiences relating to his or her process of adjusting to disability. These negative experiences can often be attributed to the perceptions of members of religious communities and historical religious ideas about disability.

In the past, certain religious tenets and principles (e.g., Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) argued that individuals with disabilities were burdens or punishments from god [10,20]. Judaism sees individuals with disabilities as negative mortifications of god. In essence, Judaism assumes that disabilities are celestial punishments and that individuals with disabilities are tainted. The contamination of these people is also believed to be capable of spreading and polluting society [20]. Israelites believed that men with disabilities were less than men and excluded them from the temple. In Christianity, persons with disabilities are believed to be the vessels through which God conveys mercy and power, born to illustrate God’s power [21]. Christian theologians believe that the presence of disabilities, specifically intellectual disabilities, indicates the possibility of inheritable immorality [22]. This belief was used to support the eugenics movements in the United States and Nazi Germany [20]. Of the Abrahamic traditions, Islamic beliefs are the most inclusive and supportive of civil protection for persons with disabilities [20]. Islam believes that excluding individuals with disabilities from the general and religious community is an act of indignity and disrespect toward Allah [21]. In Islam individuals with disabilities are not identified by their disabilities in a social or religious context [22]. Disabilities are also considered to be gatekeepers for opportunities of restitution [23]. In sum, the Islamic belief system affirms the normalization of individuals with disabilities and considers disability to fall within the vast range of characteristics of the human condition, as prescribed by Allah [22].

Religion can play a significant role in the overall quality of life of individuals with disabilities. Turner et al. [24] conducted a study examining the religious expression of 29 adults with intellectual disabilities, including Muslims, Hindus, Christians and Catholics. They found that the participants had strong, lucid, and positive understandings of religious identity. In addition, the participants were most likely to employ religious expression during incidences of indifference and hostility. The study identified two main benefits of religion [24]. The first was religious expression. The participants who had faith exhibited an ability to establish meaning and cope with many aspects of their lives. The second was religious connectedness, or the participants’ sense belonging to God and the community.

Religion can help individuals with disabilities cope, find meaning in their newly constructed reality, achieve contentment and create new goals [15,16,18]. Pragament and Brant [19] showed that religion can produce either successful or unsuccessful mechanisms of coping, depending on the situation and the individual. For instance, one individual may use religion as a source of strength in order to cope with a situation, while another may have negative perceptions of religion as a result of unfavorable experiences relating to his or her process of adjusting to disability. These negative experiences can often be attributed to the perceptions of members of religious communities and historical religious ideas about disability.

In the past, certain religious tenets and principles (e.g., Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) argued that individuals with disabilities were burdens or punishments from god [10,20]. Judaism sees individuals with disabilities as negative mortifications of god. In essence, Judaism assumes that disabilities are celestial punishments and that individuals with disabilities are tainted. The contamination of these people is also believed to be capable of spreading and polluting society [20]. Israelites believed that men with disabilities were less than men and excluded them from the temple. In Christianity, persons with disabilities are believed to be the vessels through which God conveys mercy and power, born to illustrate God’s power [21]. Christian theologians believe that the presence of disabilities, specifically intellectual disabilities, indicates the possibility of inheritable immorality [22]. This belief was used to support the eugenics movements in the United States and Nazi Germany [20]. Of the Abrahamic traditions, Islamic beliefs are the most inclusive and supportive of civil protection for persons with disabilities [20]. Islam believes that excluding individuals with disabilities from the general and religious community is an act of indignity and disrespect toward Allah [21]. In Islam individuals with disabilities are not identified by their disabilities in a social or religious context [22]. Disabilities are also considered to be gatekeepers for opportunities of restitution [23]. In sum, the Islamic belief system affirms the normalization of individuals with disabilities and considers disability to fall within the vast range of characteristics of the human condition, as prescribed by Allah [22].

Religion can play a significant role in the overall quality of life of individuals with disabilities. Turner et al. [24] conducted a study examining the religious expression of 29 adults with intellectual disabilities, including Muslims, Hindus, Christians and Catholics. They found that the participants had strong, lucid, and positive understandings of religious identity. In addition, the participants were most likely to employ religious expression during incidences of indifference and hostility. The study identified two main benefits of religion [24]. The first was religious expression. The participants who had faith exhibited an ability to establish meaning and cope with many aspects of their lives. The second was religious connectedness, or the participants’ sense belonging to God and the community.

The influence of religion on decision-making

Faver [25] attested that people of faith often depend on their religion to uphold ethical standards and implement social change. Similarly, Blanks and Smith [20] showed that faith is vital in shaping the attitudes of family members and their decisions regarding seeking appropriate services and interventions for children or other persons with disabilities. Schieman [11] conducted a study in which 1,882 individuals with various education levels, socioeconomic statuses, and religious affiliations were surveyed to determine the importance of religion in decision-making. The results revealed that participants with more education were less likely to recognize religion as a primary guide in their decision making process, but tended to supplement their problem-solving strategies with religious teachings and guidance from the Bible. Although education can supply people with the tools to address an array of problems and make decisions based on their own understanding and personal control [26], there is a gap in the literature examining the influence of religion on the decision - making processes of people with disabilities [27].

Risk-taking

Pregnancy always bears unknown risks since perinatal birth defects can occur at any point during the gestation phase. For this reason, researchers and bioethicists have debated the concept of the selection of existence [28-32]: Who in what form or shape is allowed to come into the world? Society cannot seem to arrive at a consensus regarding whether it is morally objectionable to forbid people with inheritable disabilities and genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome, syndactyly, Tay-Sachs disease, muscular dystrophy, congenital deafness, and sickle cell anemia, from taking the chance of having potentially disabled off spring. Furthermore, advanced maternal and paternal age is believed to significantly elevate the odds of conceiving an infant with a disability [31,33]. Understandably, society sometimes views and judges with preconceived negative connotations the risk two well-informed adults of middle - or non - traditionally childbearing age take when they choose to have a baby.

Reproduction decisions are partially influenced by the magnitude of perceived risk that two adults are willing to bear [30,33]. An action that involves accepting uncertainty and possible undesirable consequences is considered to represent risk-taking [34-36]. Risk-taking is natural for many individuals and can manifest in various behaviors [35]. Primary risk behaviors that are commonly discussed in the literature include gambling, reckless driving, promiscuity, sensation-seeking, impulsive tendencies, and participating in dangerous sports [34,37,38]. Most literature regarding risk-taking focuses on the actions a person takes that produce uncertainty; however, it is important to recognize that individuals may also acquire risk when refraining from action [34]. Three factors have been identified as contributing to such inaction are procrastination, avoidance, and regret avoidance [34]. Personal experience and individual attitudes can also foster a risk-taking mindset [39]. People with parents who are highly educated are more inclined to choose risky paths in life [40]. Moreover, women tend to be more risk averse than men [41]. It is, therefore, important to acknowledge individuals’ attitudes concerning the level of risk in every aspect of their lives. The outcome of taking risk or not taking risk can help predict an individual’s future. For couples in which at least one member has a disability, it is especially important to recognize the risk of bearing a child with a disability [42]. With a sound understanding of the risks associated with passing on an inheritable disease or disability to their offspring, such couples can wisely weigh the consequences and joys of being parents to children with disabilities.

The selective reproduction of desirable characteristics in the human race is a hotly contested issue that draws support from such eugenicists as Charles Darwin, Peter Singer and opposition from bioethicists and disability rights advocates. Sterilization, when used as preventative medicine, offers individuals who are carriers of defective genes the choice to prevent passing these genes on to their offspring. In the past, the United States, Australia, and Nazi Germany systematically practiced eugenics on citizens with disabilities [5]. Governments often used social costs, risk aversion theory, and the principle of utilitarianism to justify the implementation of such a policy to prevent people with genetic defects and inheritable diseases from producing babies likely to be burdens to society. Prior research has focused solely on the unethical practice of forcing the sterilization of people with mental retardation. The present study was the first to examine attitudes toward the voluntary practice of eugenics among people with high - risk inheritable diseases and genetic disorders. It aimed to determine what characteristics might affect individuals’ views on this topic. Specifically, the study examined the linear combination of such variables as personal religiosity, risk-taking, age, gender, a disabled family member, college major, and race. In so doing, it addressed the following research question: What are the relationships between personal characteristics (e.g., race, gender, having a family member with a disability), attitudes toward risk-taking and the importance of religion, and people’s views on potential offspring with genetic disorders?

Reproduction decisions are partially influenced by the magnitude of perceived risk that two adults are willing to bear [30,33]. An action that involves accepting uncertainty and possible undesirable consequences is considered to represent risk-taking [34-36]. Risk-taking is natural for many individuals and can manifest in various behaviors [35]. Primary risk behaviors that are commonly discussed in the literature include gambling, reckless driving, promiscuity, sensation-seeking, impulsive tendencies, and participating in dangerous sports [34,37,38]. Most literature regarding risk-taking focuses on the actions a person takes that produce uncertainty; however, it is important to recognize that individuals may also acquire risk when refraining from action [34]. Three factors have been identified as contributing to such inaction are procrastination, avoidance, and regret avoidance [34]. Personal experience and individual attitudes can also foster a risk-taking mindset [39]. People with parents who are highly educated are more inclined to choose risky paths in life [40]. Moreover, women tend to be more risk averse than men [41]. It is, therefore, important to acknowledge individuals’ attitudes concerning the level of risk in every aspect of their lives. The outcome of taking risk or not taking risk can help predict an individual’s future. For couples in which at least one member has a disability, it is especially important to recognize the risk of bearing a child with a disability [42]. With a sound understanding of the risks associated with passing on an inheritable disease or disability to their offspring, such couples can wisely weigh the consequences and joys of being parents to children with disabilities.

The selective reproduction of desirable characteristics in the human race is a hotly contested issue that draws support from such eugenicists as Charles Darwin, Peter Singer and opposition from bioethicists and disability rights advocates. Sterilization, when used as preventative medicine, offers individuals who are carriers of defective genes the choice to prevent passing these genes on to their offspring. In the past, the United States, Australia, and Nazi Germany systematically practiced eugenics on citizens with disabilities [5]. Governments often used social costs, risk aversion theory, and the principle of utilitarianism to justify the implementation of such a policy to prevent people with genetic defects and inheritable diseases from producing babies likely to be burdens to society. Prior research has focused solely on the unethical practice of forcing the sterilization of people with mental retardation. The present study was the first to examine attitudes toward the voluntary practice of eugenics among people with high - risk inheritable diseases and genetic disorders. It aimed to determine what characteristics might affect individuals’ views on this topic. Specifically, the study examined the linear combination of such variables as personal religiosity, risk-taking, age, gender, a disabled family member, college major, and race. In so doing, it addressed the following research question: What are the relationships between personal characteristics (e.g., race, gender, having a family member with a disability), attitudes toward risk-taking and the importance of religion, and people’s views on potential offspring with genetic disorders?

METHOD

Participant recruitment and data collection

Participants were recruited on a volunteer basis from classes that were required for each major. The business students were recruited from a large public university in a southern state. The physician assistant and engineering students were recruited from a large public university in a southwestern state. An email was sent by a person on the research team to the instructor of each selected course following Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Once the instructor’s agreement was obtained, a member of the research team visited the class to explain the study and ask for volunteers. Among the business students, 198 surveys were distributed, and 193 were collected for a response rate of 97%. For the physician assistant and engineering students, 280 surveys were distributed and 258 were collected for a response rate of 92%. The overall response rate for this study was 93.9%.

Data preparation and analysis

The survey data were entered into a shared file by the research team members who collected the data at the two campuses. The data were examined for accuracy and outliers prior to conducting the analyses. Several multivariate outliers (n = 23) were identified in the sample and removed. Of these outliers, 10 came from the engineering student group, 2 came from the business student group and 11 came from the physician assistant group. The rest of the participants were retained for the final sample. A General Linear Model (GLM) was tested to answer the research question.

Participant characteristics

Participants included students (N = 426) from two large public universities across three distinct academic majors: engineering (n = 113), physician assistant (n = 124), and business (n = 189). Of the sample, 47.1% were female (n = 201), 71.0% were undergraduate (n = 303), and 23.7% reported having a family member with a disability (n = 101). Race and ethnicity were reported as follows: 42.4% (n = 181) was White, 42.2% (n = 180) was Hispanic, 10.1% (n = 43) were Asian, 2.6% (n = 11) were Black or African American, and 1.9% (n = 8) were multicultural. Four participants elected not to report a racial or ethnic identity. Religious affiliations were reported as follows: 37.2% (n = 159) was Christian, 35.8% (n = 153) was Catholic, 6.3% (n = 27) were Atheist and 18.0% (n = 77) was another religion. Eleven participants elected not to indicate a religious affiliation. The average age of the participants was 22.85 (sd = 3.75) years old.

MEASURES

Attitudes

The construct of attitudes toward eugenics is a latent variable. For the purpose of the study, the authors modified the Scale of Attitudes toward Mental Retardation and Eugenics (AMRE) developed by Antonak, Fielder, and Mulick [43]. AMRE comprises 32 five-point Likert-type statements measuring attitudes toward the application of eugenics to treat people with intellectual disability. The scale had an internal consistency coefficient alpha of 0.93. For the present study, 13 items were selected according to relevance. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement according to a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) with such statements as, “prospective parents with genetic disorders should be made aware of the likelihood of passing debilitating conditions on to their offspring” and “due to debilitating medical conditions, children with genetic disorders may find it hard to lead a full life when they grow up compared with their peers without disabilities”. A higher score on this scale indicates more negative attitudes toward individuals with genetic disorders. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was 0.785.

Risk avoidance

The construct of risk avoidance was measured using the risk - taking questionnaire. This scale contains 11 items with such statements as “I’m the kind of the person who avoids risks.” Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement according to a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = agree very much to 5 = disagree very much). A higher score on this scale indicates a greater likelihood of being open to risk-taking. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was 0.810.

Religiosity

The construct of the importance of religion was measured using the dimensions of religious ideology importance scale [44]. This instrument contains six items and asks participants to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with different statements about their personal feelings concerning about the importance of religion. A sample item is “My ideas about religion are one of the most important parts of my philosophy of life.” Respondents answer each statement according to a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). There is an option for “no response” in the middle of the scale (4). A higher score on this scale indicates stronger feelings concerning the importance for religion. The scale is non-denominational, meaning that it includes no references to a particular type of religion. Therefore, participants’ religious affiliations do not impact responses. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was 0.886.

RESULTS

The research question was addressed by testing a General Linear Model (GLM) including select variables related to the outcome variable (attitude scale score).We tested several main effects as fixed factors, including gender, race, college major, and whether or not the respondent had a family member with a disability (yes/no). We tested two covariates, risk avoidance and importance of religion. We also tested the interaction between gender and having a family member with a disability. The model was significant (p < 0.001, adjusted r2 of 0.078). Significant main effects were found for race [F (4,378) = 2.538, p = 0.04, η² = 0.026], risk avoidance [F (1,378) = 12.536, p < 0.001, η² = 0.032], and importance of religion [F (1,378) = 5.530, p = 0.019, η² = 0.014]. A significant interaction was observed between gender and having a family member with a disability [F (1,378) = 7.288, p = 0.007, η² = 01.019]. See table1 for a correlation matrix, means and standard deviations of all model variables and table 2 for model results.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Gendera | 0.53 | 0.5 | – | ||||||

| 2. Raceb | 1.8 | 0.95 | -0.075 | – | |||||

| 3. Majorc | 1.98 | 0.75 | 0.173** | -0.134** | – | ||||

| 4. Family member with a disabilityd | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.012 | -0.072 | 0.027 | – | |||

| 5. Risk avoidance scale | 26.5 | 7.08 | 0.271** | 0.026 | 0.189** | -0.001 | – | ||

| 6. Religiosity importance scale | 24.42 | 7.9 | -0.143** | -0.057 | -0.091 | -0.007 | -0.151** | – | |

| 7. Attitude scale | 38.75 | 7.14 | 0.038 | 0.034 | -0.127 | -0.078 | -0.146** | -0.100* | – |

Note: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, two - tailed.

a: Female = 0, Male = 1;

b: Hispanic or Latino = 1, White = 2, Asian American = 3, Black or African American = 4, Native American = 5, Multicultural = 6;

c: Physician Assistant = 1, Business = 2, Engineering = 3;

d: No = 0, Yes = 1.

a: Female = 0, Male = 1;

b: Hispanic or Latino = 1, White = 2, Asian American = 3, Black or African American = 4, Native American = 5, Multicultural = 6;

c: Physician Assistant = 1, Business = 2, Engineering = 3;

d: No = 0, Yes = 1.

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η² |

| Model | 1064.66 | 11 | 187.7 | 4 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Intercept | 23545.7 | 1 | 23545.7 | 501.4 | 0 | 0.57 |

| Gender | 8.4 | 1 | 8.4 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 0 |

| Race | 476.78 | 4 | 119.2 | 2.54 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Major | 164.77 | 2 | 82.39 | 1.76 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| Family member | 93.18 | 1 | 93.18 | 1.98 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Risk avoidance | 588.65 | 1 | 588.65 | 12.54 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Religiosity | 259.67 | 1 | 259.67 | 5.53 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Gender x family member | 342.24 | 1 | 342.24 | 7.29 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Error | 17749.6 | 378 | 46.96 | |||

| Total | 604920 | 390 | ||||

| Corrected total | 19814.3 | 389 |

Note: r2 = 0.104, adjusted r2 = 0.078.

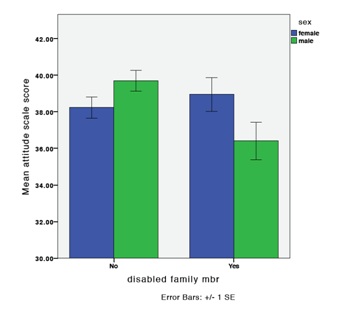

A pre - planned contrast in marginal means between racial groups showed that students of Asian descent had significantly more negative attitudes toward potential offspring with genetic disorders (p = 0.039). Figure 1 shows a graph of the contrast. A further analysis was conducted to explore the interaction between gender and having a family member with a disability. The results showed that for females, there were no group differences between those who had family members with disabilities and those who did not; however, for males, those who had family members with disabilities reported significantly more positive attitudes toward offspring with genetic disorders. Figure 2 shows a bar graph of this interaction effect.

A pre - planned contrast in marginal means between racial groups showed that students of Asian descent had significantly more negative attitudes toward potential offspring with genetic disorders (p = 0.039). Figure 1 shows a graph of the contrast. A further analysis was conducted to explore the interaction between gender and having a family member with a disability. The results showed that for females, there were no group differences between those who had family members with disabilities and those who did not; however, for males, those who had family members with disabilities reported significantly more positive attitudes toward offspring with genetic disorders. Figure 2 shows a bar graph of this interaction effect.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the attitudes of college students toward the voluntary practice of eugenics among people with high-risk genetic disorders. We were particularly interested in identifying any differences across college majors (i.e., physician assistant, business, and engineering). We also considered religiosity and risk-taking, as well as demographic factors and experiences of family members with disabilities. While the prediction power was modest (r2 = 0.078), these findings have interesting implications for understanding what factors influence attitudes toward eugenics. Considered alone, the physician assistant students had more negative attitudes toward offspring with congenital disabilities than students in business or engineering, but these differences were no longer visible in the model after risk-taking was included. Patterns of risk-taking were also observed to differ across college majors, likely influencing the results. Race and the importance of religion also emerged as significant predictors, suggesting, consistent with other study findings [45-47], that culture influences the formation of attitudes toward disabilities. Specifically, students identifying as Asian expressed more negative attitudes toward potential offspring with congenital disorders. A negative relationship was also found between religiosity and the outcome measure of attitudes, meaning that a greater expressed importance of religion was associated with more positive attitudes toward offspring with congenital disabilities [46]. With respect to risk - taking, a higher score on the risk - taking scale (e.g., more open to risk) was associated with a lower score on the attitude scale (indicating more positive attitudes toward offspring with congenital disabilities). Another interesting finding was an interaction between experience with family disabilities and gender: for men, having a family member with a disability was associated with more positive attitudes toward potential offspring with congenital conditions; however, this was not the case for females. Nevertheless, females had more positive attitudes toward such offspring on average, regardless of family experience with disability.

These results, while important, must be considered within the context of several limitations. Our volunteer sample was recruited from selected courses offered to students of particular majors. While our response rate was high, we cannot be certain that the responses were representative. Social desirability bias may have influenced how participants answered the questions. Additional research is needed to identify and clarify the factors that influence attitudes toward disability, particularly with respect to eugenics. Because the study participants were recruited from two institutions of higher education located in a southern state and a southwestern state, the generalizability of the findings may not be applicable to individuals who live in other parts of the United States. The study sample was drawn from two universities located in two different states. We acknowledge that we used a convenience sample because the first two authors were affiliated with these universities.

Attitudes regarding eugenics are closely tied to attitudes toward disabilities and disabling conditions. A common assumption is that quality of life is dependent on good health; therefore, any medical condition or disability will negatively impact quality of life [48]. This differs significantly from the perceptions of many people who have disabilities or are involved in rehabilitation and disability studies, in which the philosophy is disabilities are a natural part of human existence and that quality of life is dependent on such factors as personal perceptions of well - being, choice, control, self - concept, and social environment [5,48]. These two views delineate distinct models of disability: the medical model and the sociopolitical model. The medical model is diagnosis - driven, purporting that disability is a pathology or deformity [5]. The sociopolitical model suggests that the greatest disability - related barrier is the discrimination, prejudice, and lack of opportunity experienced by people with disabilities both in the United States and worldwide [5]. Disability in and of itself is not a disadvantage, and advocacy and social change may address the kinds of barriers that people with disabilities experience. It follows naturally that an individual’s perceptions of disabilities and their impact on quality of life will influence the individual’s feelings about eugenics and babies with genetic disorders and congenital conditions.

With the expansion of prenatal testing, greater importance has been assigned to understanding attitudes toward children (born or unborn) with congenital conditions. Prenatal testing can be a hotly debated issue, especially in terms of who decides and defines what traits are desirable in babies. What would parents who dream of their child becoming the next great athlete or mathematician do if their unborn child had a disability? The results of studies with parents at risk of carrying children with congenital disorders (e.g., down syndrome, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida) have shown that access to information about resources available to families and the quality of life of children with disabilities can impact couples’ decision [49]. Prior research suggests that major barriers in obtaining health care services, as described by people with disabilities, are the negative attitudes and behaviors of health personnel [50]. Particularly among individuals trained from a solely medical-model perspective, attitudes toward disability may affect the treatment of individuals and families, and the provision of care and advice. This is especially true among medical professionals who consider the severity of disability impairment to be directly related to quality of life [5,48].

The results also suggest that cultural factors, such as those related to race/ethnicity or religious values, also impact disability attitudes. Consistent with the results from our sample, previous studies have found that some Asian cultures perceive disability as a family burden; this may lead individuals to express more negative attitudes toward disability [49,51]. In some cultures, disability is perceived to be a punishment from God and, therefore, a source of shame [46,52]. Studies suggest that exposure to information about and experience with persons with disabilities, including those with congenital conditions, may improve knowledge and comfort addressing disability issues. However, we have little evidence that information alone influences attitudes and beliefs about disability and eugenics [53]. Other methods, such as social influence, ongoing contact with individuals with disabilities, and impression management approaches may be more useful in changing attitudes [54-56]. These findings are preliminary and need to be expanded and replicated before strong conclusions can be drawn. However, the findings that experience with disability may have a positive influence on values, particularly among men, and that risk avoidance and culture may also influence these values may be useful in counseling, health and rehabilitation settings.

In conclusion, people come in different shapes and sizes. The selection of existence is arbitrary and implies that only healthy individuals, and not those with disabilities, are desirable for society. The present study sheds light on the public’s attitudes toward the voluntary practice of eugenics. Race, gender, college major, religiosity, a disabled family member and possession of a risk - taking trait are found to be important determinants. The direction of future research is suggested to focus on individuals with existing genetic disorders and inheritable diseases. Similar studies may also be replicated in countries where abortion procedures are either strictly prohibited or easily available.

These results, while important, must be considered within the context of several limitations. Our volunteer sample was recruited from selected courses offered to students of particular majors. While our response rate was high, we cannot be certain that the responses were representative. Social desirability bias may have influenced how participants answered the questions. Additional research is needed to identify and clarify the factors that influence attitudes toward disability, particularly with respect to eugenics. Because the study participants were recruited from two institutions of higher education located in a southern state and a southwestern state, the generalizability of the findings may not be applicable to individuals who live in other parts of the United States. The study sample was drawn from two universities located in two different states. We acknowledge that we used a convenience sample because the first two authors were affiliated with these universities.

Attitudes regarding eugenics are closely tied to attitudes toward disabilities and disabling conditions. A common assumption is that quality of life is dependent on good health; therefore, any medical condition or disability will negatively impact quality of life [48]. This differs significantly from the perceptions of many people who have disabilities or are involved in rehabilitation and disability studies, in which the philosophy is disabilities are a natural part of human existence and that quality of life is dependent on such factors as personal perceptions of well - being, choice, control, self - concept, and social environment [5,48]. These two views delineate distinct models of disability: the medical model and the sociopolitical model. The medical model is diagnosis - driven, purporting that disability is a pathology or deformity [5]. The sociopolitical model suggests that the greatest disability - related barrier is the discrimination, prejudice, and lack of opportunity experienced by people with disabilities both in the United States and worldwide [5]. Disability in and of itself is not a disadvantage, and advocacy and social change may address the kinds of barriers that people with disabilities experience. It follows naturally that an individual’s perceptions of disabilities and their impact on quality of life will influence the individual’s feelings about eugenics and babies with genetic disorders and congenital conditions.

With the expansion of prenatal testing, greater importance has been assigned to understanding attitudes toward children (born or unborn) with congenital conditions. Prenatal testing can be a hotly debated issue, especially in terms of who decides and defines what traits are desirable in babies. What would parents who dream of their child becoming the next great athlete or mathematician do if their unborn child had a disability? The results of studies with parents at risk of carrying children with congenital disorders (e.g., down syndrome, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida) have shown that access to information about resources available to families and the quality of life of children with disabilities can impact couples’ decision [49]. Prior research suggests that major barriers in obtaining health care services, as described by people with disabilities, are the negative attitudes and behaviors of health personnel [50]. Particularly among individuals trained from a solely medical-model perspective, attitudes toward disability may affect the treatment of individuals and families, and the provision of care and advice. This is especially true among medical professionals who consider the severity of disability impairment to be directly related to quality of life [5,48].

The results also suggest that cultural factors, such as those related to race/ethnicity or religious values, also impact disability attitudes. Consistent with the results from our sample, previous studies have found that some Asian cultures perceive disability as a family burden; this may lead individuals to express more negative attitudes toward disability [49,51]. In some cultures, disability is perceived to be a punishment from God and, therefore, a source of shame [46,52]. Studies suggest that exposure to information about and experience with persons with disabilities, including those with congenital conditions, may improve knowledge and comfort addressing disability issues. However, we have little evidence that information alone influences attitudes and beliefs about disability and eugenics [53]. Other methods, such as social influence, ongoing contact with individuals with disabilities, and impression management approaches may be more useful in changing attitudes [54-56]. These findings are preliminary and need to be expanded and replicated before strong conclusions can be drawn. However, the findings that experience with disability may have a positive influence on values, particularly among men, and that risk avoidance and culture may also influence these values may be useful in counseling, health and rehabilitation settings.

In conclusion, people come in different shapes and sizes. The selection of existence is arbitrary and implies that only healthy individuals, and not those with disabilities, are desirable for society. The present study sheds light on the public’s attitudes toward the voluntary practice of eugenics. Race, gender, college major, religiosity, a disabled family member and possession of a risk - taking trait are found to be important determinants. The direction of future research is suggested to focus on individuals with existing genetic disorders and inheritable diseases. Similar studies may also be replicated in countries where abortion procedures are either strictly prohibited or easily available.

REFERENCES

- Langtree L, Langtree I (2008) World facts and statistics on disabilities and disability issues. Disabled World, New York, USA.

- Brault MW (2012) Americans with disabilities: 2010. Disability, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Gilmore L, Campbell J, Cuskelly M (2003) Developmental Expectations, Personality Stereotypes, and Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: Community and teacher views of Down syndrome. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 50: 65-76.

- Yazbeck M, McVilly K, Parmenter TR (2004) Attitudes Toward People with Intellectual Disabilities An Australian Perspective. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 15: 97-111.

- Smart J (2016) Disability, Society, and the Individual (3rd edn), Pro-Ed, Texas, USA.

- Terrell V (2012) Celebrating Just Living with Disability in the Body of Christ. The Ecumenical Review 64: 562-574.

- Barr GW (2000) Out of Sight, Out of Mind: There is a kinder, gentler, subtler discrimination these days. America, New York, USA.

- Allen GE (2011) Eugenics and modern biology: critiques of eugenics, 1910-1945. Ann Hum Genet 75: 314-325.

- Stubblefield A (2007) “Beyond the Pale”: Tainted Whiteness, Cognitive Disability, and Eugenic Sterilization. Hypatia 22: 162-181.

- Baynton DC (2011) ‘These pushful days’: time and disability in the age of eugenics. Health History 13: 43-64.

- Schieman S (2011) Education and the Importance of Religion in Decision Making: Do Other Dimensions of Religiousness Matter? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 570-587.

- Pew Research Center (2015) America’s Changing Religious Landscape. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Pew Research Center (2016) Religion in Everyday Life. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Alvani SR, Parvin-Hosseini SM, Alvani S (2012) Living with chronic illness and disability. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology 2: 102-110.

- Glicksman S (2011) Supporting religion and spirituality to enhance quality of life of people with intellectual disability: A Jewish perspective. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 49: 397-402.

- Johnstone B, Glass BA, Oliver RE (2007) Religion and disability: clinical, research and training considerations for rehabilitation professionals. Disabil Rehabil 29: 1153- 1163.

- Ellison CW (1983) Spiritual well being: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Psychology and Theology 11: 330-340.

- Ferriss AL (2002) Religion and the Quality of Life. Journal of Happiness Studies 3: 199-215.

- Pargament KI, Brant CR (1998) Religion and coping. In: Koenig HG (eds.). Handbook of Religion and Mental Health, Elsevier, Waltham, USA.

- Blanks AB, Smith JD (2009) Multiculturalism, Religion, and Disability: Implications for Special Education Practitioners. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities 44: 295-303.

- Miles M (2002) Some Influences of Religions on Attitudes Towards Disabilities and People with Disabilities. Journal of Religion, Disability & Health 6: 117-129.

- Miles M (2001) Martin Luther and Childhood Disability in 16th Century Germany: What Did He Write? What Did He Say? Journal of Religion, Disability, & Health 5: 5-36.

- Rispler-Chaim V (2007) Disability in Islamic Law. Springer 32: 93-171.

- Turner S, Hatton C, Shah R, Stansfield J, Rahim N (2004) Religious Expression amongst Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 17: 161-171.

- Faver CA (2004) Relational Spirituality and Social Caregiving. Social Work 49: 241-249.

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE (2003) Education, social status, and health. Aldine Transaction, New York, USA.

- Kingston PW, Hubbard R, Lapp B, Schroeder P, Wilson J (2003) Why education matters. Sociology of Education 76: 53-70.

- Coleman CH (2002) Conceiving harm: disability discrimination in assisted reproductive technologies. UCLA Law Rev 50: 17-68.

- Jurkovic D, Jauniaux E, Campbell S, Mitchell M, Lees C, et al. (1995) Diagnosing and preventing inherited disease: Detection of sickle gene by coelocentesis in early pregnancy: a new approach to prenatal diagnosis of single gene disorders. Human Reproduction 10: 1287-1289.

- McMahan J (2005) Causing Disabled People to Exist and Causing People to Be Disabled. Ethics 116: 77-99.

- Schover LR, Thomas AJ, Falcone T, Attaran M, Goldberg J (1998) Attitudes about genetic risk of couples undergoing in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod 13: 862-866.

- Shakespeare T (1998) Choices and Rights: Eugenics, genetics and disability equality. Disability & Society 13: 665-681.

- Urhoj SK, Jespersen LN, Nissen M, Mortensen LH, Nybo Andersen AM (2014) Advanced paternal age and mortality of offspring under 5 years of age: a register-based cohort study. Hum Reprod 29: 343-350.

- Keinan R, Bereby-Meyer Y (2012) Leaving It to Chance”-Passive Risk Taking in Everyday Life Judgment and Decision Making 7: 705-715.

- Roberston JP, Collinson C (2011) Positive risk taking: Whose risk is it? An exploration in community outreach teams in adult mental health and learning disability services. Health, Risk & Society 13: 147-164.

- Rosenbloom T (2003) Risk evaluation and risky behavior of high and low sensation seekers. Social Behavior and Personality 31: 375-386.

- Carlin BI, Robinson DT (2009) Fear and loathing in Las Vegas: Evidence from the black jack tables. Judgment and Decision Making 4: 385-396.

- Moreno CL, Baer JC (2012) Barriers to Prevention: Ethnic and Gender Differences in Latino Adolescent Motivations for Engaging in Risky Behaviors. Child Adolescent Social Work Journal 29: 137-149.

- Paola MD, Gioia F (2012) Risk aversion and field of study choice: The role of individual ability. Bulletin of Economic Research 64: 193-209.

- Dohemen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Sunde U (2012) The Intergenerational Transmission of Risk and Trust Attitudes. The Review of Economic Studies 79: 645- 677.

- Eckel CC, Grossman PJ (2008) Differences in the Economic Decisions of Men and Women: Experimental Evidence. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results 1: 509-519.

- Pojer B (2016) Is it objectionable to create a child as a carer for a disabled parent? Journal of Medical Ethics 42: 788-791.

- Antonak RF, Fielder CR, Mulick JA (1993) A scale of attitudes toward the application of eugenics to the treatment of people with mental retardation. J Intellect Disabil Res 37: 75-83.

- Putney S, Middleton R (1961) Dimensions and Correlates of Religious Ideologies. Social Forces 39: 285-290.

- Brown T, Mu K, Peyton CG, Rodger S, Stagnitti K, et al. (2009) Occupational therapy students’ attitudes towards individuals with disabilities: a comparison between Australia, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Res Dev Disabil 30: 1541-1555.

- Chen RK, Kotbungkair W, Brown AD (2015) A Comparison of Self-Acceptance of Disability between Thai Buddhist and American Christians. Journal of Rehabilitation 81: 52-62.

- Wolbring G (2003) Disability Rights Approach Toward Bioethics? Journal of Disability Policy Studies 14: 174-180.

- Ormond KE, Gill CJ, Semik P, Kirschner KL (2003) Attitudes of health care trainees about genetics and disability: issues of access, health care communication, and decision making. J Genet Couns 12: 333-349.

- Zanskas S, Coduti W (2006) Eugenics, euthanasia, and physician assisted suicide: An overview for rehabilitation professionals. Journal of Rehabilitation 72: 27-34.

- Tervo RC, Palmer G, Redinius P (2004) Health professional student attitudes towards people with disability. Clin Rehabil 18: 908-915.

- Stone JH (2005) Culture and disability providing culturally competent services. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, Canada.

- Sue DW, Sue D (2012) Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice, (6th edn). John Wiley, Sons Hoboken, New Jersey, USA.

- Kobe F, Mulick J (1995) Attitudes toward mental retardation and eugenics: The role of formal education and experience. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 7: 1-9.

- Chan F, Cardoso E, Chronister J (2009) Understanding psychosocial adjustment to chronic illness and disability. Springer, New York, USA.

- Chubon RA (1992) Attitudes toward disability: Addressing fundamentals of attitude theory and research in rehabilitation education. Rehabilitation Education 6: 301-312.

- Yuker HE (1994) Variables that influence attitudes toward people with disabilities: Conclusions from the data. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 9: 3-22.

Citation: Chen RK, Fleming AR, Kuhn L, Foster AL (2017) The Voluntary Practice of Eugenics: Risk-Taking and Religiosity as Determinants of Attitudes Toward Conceiving Children with Potential Genetic Disorders and Inheritable Diseases. J Phys Med Rehabil Disabil 3: 018.

Copyright: © 2017 Roy K Chen, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!