Therapeutic, Clinical and Prognostic Aspects of Uterine Rupture in the Point G Teaching Hospital, Bamako, Mali

*Corresponding Author(s):

Mamadou SimaDepartment Of Gynecology Obstetrics, Faculty Of Medicine And Odontostomatology, University Hospital Center Point G, Bamako, Mali

Tel:+223 72238485,

Email:drmsima@gmail.com

Abstract

In Mali, uterine rupture remains one of the main causes of maternal morbidity and mortality. This study aimed to describe clinical, therapeutic and prognostic aspects of the uterine rupture in the Gynecology ward of the Point G Teaching Hospital. The data were collected from patients diagnosed with uterine rupture before, during labor or in the postpartum period. Data analysis was performed using the Software SPSS version 12.0. Pearson’s Chi2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare proportions. We recorded 138 cases of uterine rupture over 16101 deliveries between January 2008 and December 2017. Uterine rupture was more frequent in women with non-scarred uterus 62.3% than in those with a scarred uterus 37.7%. The main factors associated were multiparity, oxytocin misuse and non-scarred uterine. These data show that uterine rupture remains common in Mali and is one of the leading causes of maternal and perinatal mortality.

Keywords

Clinical; Mali; Maternal mortality; Prognostic; Uterine rupture

INTRODUCTION

Uterine rupture is tearing of the uterine wall either partially or completely during pregnancy or delivery. It is a serious obstetrical condition with a poor maternal-fetal prognosis in terms of morbidity and mortality [1]. Guillemeau is the first to write on this pathology at the beginning of the 17th century. In his book in French entitled “About women pregnancy and deliveries”, he shows the seriousness of the uterine rupture in pregnant women [2]. Its curative treatment sometimes requires a mutilating surgical technique for the patient, thus definitively stopping her childbearing [3]. Uterine rupture can easily occur due to the fragility of the uterus from the existing scar that is not well vascularized. The rupture, complete or partial, is caused in most cases by uterine contractions, which is responsible for bleeding. Many studies have shown that the scarred uterus is the main risk factor for uterine rupture [4,5]. Different studies around the world have also incriminated many other risk factors for rupture like uterine expressions, oxytocin misuse, maternal age, age of pregnancy, inter-reproductive interval, uterine height and type of presentation [6,7]. On the other hand, uterine rupture can occur spontaneously on the healthy uterus during pregnancy due to pathological and/or malformative condition. The pseudo-unicorn uterus, where the egg nests in a rudimentary horn that is not very extensible, generally ruptures around the 5th month. The placenta accreta which creates a zone of fragility in the myometrium according to its invasion is also a main cause. The invasive mole and the choriocarcinoma which proliferate can lead to local destruction of the myometrium. Adenomyosis also evoked by some people [8,9].

Nowadays, uterine rupture occurs exceptionally in developed countries. In France, some studies reported 1 uterine rupture case per 1,299 births [10] while in the United States it is 1 case per 22,000 births [11]. Studies in Africa showed that uterine rupture and its related bleeding are accountable for about 33% of maternal deaths, making it one of the leading causes in developing countries [12]. In Mali, uterine rupture remains one of the main causes of maternal morbidity and mortality. In Bamako, a study reported that 20% of maternal deaths in hospitals are due to uterine rupture making it the second incriminated cause [13]. Uterine rupture is also one of the main obstetric emergencies in Mali [14]. Despite the Malian Government’s efforts and political orientations in reproductive health over the past ten years, particularly with the restructuration of referral/evacuation and the free cesarean section, uterine rupture remains a major public health problem in the country. In addition to the regional disparity in its distribution throughout the country, uterine rupture is still one of the leading causes of obstetric emergencies in tertiary hospitals in Mali. The objective of this study was to describe the epidemiological, clinical, therapeutic and prognostic aspects of uterine rupture in the Point G Teaching Hospital’s Gynecology ward.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at the Gynecology ward of the Point G Teaching Hospital in Bamako, Mali. The study covered the period between January 1st, 2008 and December 31st, 2017 and involved all the deliveries in the ward. Data were collected using a questionnaire established on the patients’ record. All uterine rupture cases diagnosed before and during labor or in the postpartum in the ward were enrolled. Upon admission, patients underwent a complete clinical examination and benefited from emergency care. Uterine rupture diagnosis was essentially clinical for most of the cases. The management began with taking at least one large-caliber venous route for infusion of fluids (macromolecules), rhesus grouping, hemoglobin level dosage and delivery of a blood voucher (availability of a compatible blood bag). Patients were then urgently transferred into the surgery ward for emergency surgery. Details related to surgical techniques used such as hysterorrhaphy and subtotal or total hysterectomy were recorded as well as obstetrical history and age of the patient. A blood transfusion was performed in all patients with hemoglobin levels less than 7 g/dl or anemia clinical signs. In addition to analgesic treatment, antibiotic therapy was systematically initiated and lasted 7 to 10 days depending on the infectious score. Patients were followed up until discharge and reexamined a month later during the postnatal care visit.

Data entry and analysis were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Software (SPSS for Windows version 12.0; SPSS Inc., IL, USA). Pearson’s Chi2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare proportions. The significance level was set at 5%. The variables studied were age, occupation, marital status, admission mode, personal history (medical and surgical), family history, mode of delivery, maternal-fetal complications history, Apgar score, newborn development over the first 7 days of his life, surgical procedure performed and blood transfusion status.

RESULTS

During the 10 years of data collection, 138 cases of uterine rupture were observed for 16101 births, representing a frequency of 0.86% (one case of uterine rupture for 117 births). In total, 52 cases of rupture (37.7%) occurred in the scarred uterus while 86 others occurred in the non-scarred uterus.

Characteristics of the study population

During the study period, parturient women aged 26 to 35 years 60.1% (83/138) were the most frequently observed. Of the 138 patients affected by uterine rupture, 83.3% (115/138) were uneducated and 92% (127/138) of them were housewives. In term of residence, 34.8% (48/138) came from municipalities outside Bamako (Table 1).

|

|

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Maternal Age (Year) |

||

|

15 - 25 |

35 |

25.4 |

|

26 - 35 |

83 |

60.1 |

|

36 - 45 |

19 |

13.8 |

|

46 - 55 |

1 |

0.7 |

|

Education |

||

|

None |

115 |

83.3 |

|

Primary |

18 |

13 |

|

Secondary |

5 |

3.6 |

|

Occupation |

||

|

Housekeepers |

127 |

92.0 |

|

Student |

1 |

0.7 |

|

Shopkeeper |

4 |

2.9 |

|

Manager |

1 |

0.7 |

|

Nurse |

1 |

0.7 |

|

Animator |

1 |

0.7 |

|

Seamstress |

2 |

1.4 |

|

Secretary |

1 |

0.7 |

|

Residency |

||

|

Commune I of Bamako |

35 |

25.4 |

|

Commune II of Bamako |

4 |

2.9 |

|

Commune III of Bamako |

12 |

8.7 |

|

Commune IV of Bamako |

11 |

8.0 |

|

Commune V of Bamako |

16 |

11.6 |

|

Commune VI of Bamako |

12 |

8.7 |

|

Outside Bamako |

48 |

34.8 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population.

Etiological factors

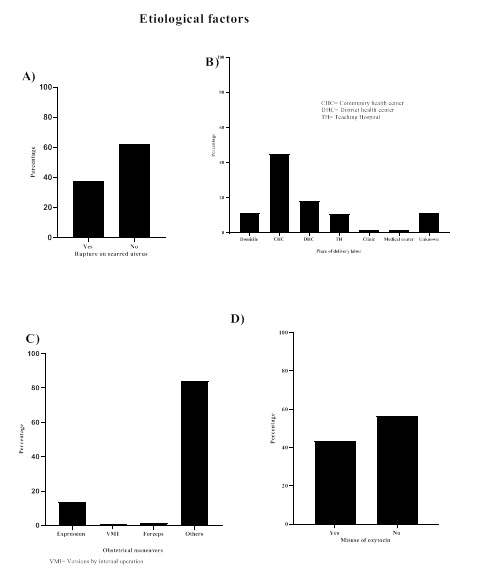

Among the cases of uterine rupture, 62.3% (86/138) of the cases had a non-scarred uterus while 37.7% (52/138) had a scarred uterus [Figure 1A]. Most cases of rupture 44.9% (62/138) were reported in women who had been admitted to Community Health Center (CHC) for labor during childbirth [Figure 1B]. Uterine expression was the most commonly used obstetric maneuver with 13.7% (19/138) [Figure 1C]. Oxytocic were misused in 43.4% (60/138) of the patients in the current study [Figure 1D].

Figure 1: Frequency of etiological factors in women with uterine rupture, Point G Teaching Hospital.

Figure 1: Frequency of etiological factors in women with uterine rupture, Point G Teaching Hospital.

Misuse of oxytocin was observed in 19.2% of the uterine rupture on the scarred uteri and 58.1% of cases of uterine rupture on the unscarred uteri. This difference was statically significant (Fisher exact test, p<0.001) [Table 2].

|

Misuse of oxytocin |

Non-scarred uterus |

Scarred uterus |

P-value* |

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

|

|

Yes |

50 (58.1) |

10 (19.2) |

1 |

|

No |

36 (41.9) |

42(80.8) |

0.001 |

|

Total |

86 (100) |

52 (100) |

|

|

Place of delivery labor |

Non-scarred uterus |

Scarred uterus |

p-value* |

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

|

|

CHC |

46 (53.5) |

16 (30.8) |

1 |

|

DHC |

14 (16.3) |

11 (21.1) |

0.12 |

|

Domicile |

7 (8.1) |

9 (17.3) |

0.03 |

|

TH |

7 (8.1) |

8 (15.4) |

0.06 |

|

Clinique |

1 (1.2) |

1 (1.9) |

0.46 |

|

Medical Center |

2 (2.3) |

0 (0) |

1 |

|

Unknown |

9 (10.5) |

7 (13.5) |

0.21 |

|

Total |

86 (100) |

52 (100) |

|

Table 2: Distribution of uterine rupture cases according to the uterine status (scarred or not), the place of delivery labor and the misuse of oxytocin.

*Fisher exact Tests; CHC= Community Health Center; DHC= District Health Center; TH=Teaching Hospital

Hysterorrhaphy with tubal ligation was the most commonly used surgical technique for the management of patients, accounting for 46.4% (64/138) of cases, while 10.8% (15/138) underwent total hysterectomy [Table 3]. Prognostic factors

The majority of deliveries took place in CHC, 53.5%, followed by DHC with 16.3% and clinics and home with 8.1 each. The difference with other places of labor delivery was not statistically significant except for home (p=0.03) [Table 2].

|

Treatment |

Frequency |

Percentage |

95% Confidence interval |

|

Hysterorrhaphy with tubal ligation |

64 |

46.4 |

38.17 - 54.73 |

|

Hysterorrhaphy without tubal ligation |

38 |

27.5 |

20.28 - 35.78 |

|

Subtotal hysterectomy |

21 |

15.2 |

9.67 - 22.32 |

|

Total hysterectomy |

15 |

10.9 |

6.21 - 17.29 |

|

Total |

138 |

100 |

Table 3: Distribution of patients by type of surgery.

The cases of death were more frequently observed in non-scarred uteri 66.7% (12/18) than in scarred uteri 33.3% (6/18). The same observation was made for anemia 63.6% (21/33) and endometritis 83.3% (5/6). On the other hand, scarring of the uterus has progressed more frequently to parietal infection 66.7% (12/18). The absence of complications in the postoperative period was more frequently observed in non-scarred uteri 60.6% (43/71). These observations of different frequencies according to the scarring status of the uterus were not statistically significant (all p-values were higher than 0.05 with a Fisher’s exact test) [Table 4].

|

|

Scarred uterus |

Non-scarred uterus |

Total |

p |

|

Complications |

n (%) |

n |

n |

|

|

Anemia |

12 (36.4) |

21 (63.6) |

33 |

1 |

|

Death |

6 (33.3) |

12 (66.7) |

18 |

1 |

|

Endometritis |

1 (16.7) |

5 (83.3) |

6 |

0.64 |

|

Parietal infection |

4 (66.7) |

2 (33.3) |

6 |

0.2 |

|

Peritonitis |

1 (50) |

1 (50) |

2 |

1 |

|

Sepsis |

0 (0) |

1 (100) |

1 |

1 |

|

Phlebitis |

0 (0) |

1 (100) |

1 |

1 |

|

None |

28 (39.4) |

43 (60.6) |

71 |

0.83 |

|

Total |

52 (37.7) |

86 (62.3) |

138 |

Table 4: Distribution of patients by post-operative complications and scarring status of the uterus.

Women with fetal weight greater than 4000g were 3 times more likely to experience uterine rupture compared to those with fetal weight between 2500g - 4000g (p=0.04). Women who did not receive anti-anemic prophylaxis were more likely to die from uterine rupture as compared to those who received it, adjusted OR prophylaxis=20.08 (1.97 - 204.86); p=0.002. Similarly, women who did not receive an antibiotic therapy were 24 times more likely to die from uterine rupture (p=0.01), [Table 5].

|

Factors |

OR (95% CI) |

ORa (95 % CI) |

LR-test |

|

General signs/symptoms |

|||

|

Blood pressure |

|||

|

≥ 80/50 mm Hg (reference) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

< 80/50 mm Hg |

22.75 (6.65 - 77.8) |

44.1 (4.55 - 427.1) |

< 0.001 |

|

Obstetrical signs |

|||

|

Type of rupture |

|||

|

Complete (reference) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Under serosa |

0.31 (0.09 - 1.13) |

5.14 (0.5 - 52.66) |

0.15 |

|

Fetal weight |

|

|

|

|

2500 g - 4000 g (reference) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

< 2500 g |

0.54 (0.11 - 2.59) |

0.05 (0 - 1.22) |

0.06 |

|

> 4000 g |

3.15 (0.84 - 11.83) |

12.96 (1.12 - 149.83) |

0.04 |

|

Management factors |

|||

|

Anti-anemic prophylaxis |

|||

|

Yes (reference) |

1 |

|

|

|

No |

1.94 (0.71 - 5.27) |

20.08 (1.97 - 20486) |

0.002 |

|

Antibiotic therapy |

|||

|

Yes |

1 |

|

|

|

No |

24.82 (5.61 -109.8) |

25.88 (1.66 - 402.88) |

0.01 |

|

Subtotal hysterectomy |

|||

|

No |

1 |

|

|

|

Yes |

3.5 (1.14 -10.72) |

44.35 (4.17 - 472.14) |

< 0.001 |

|

Low-track delivery |

|||

|

No |

1 |

|

|

|

Yes |

5.8 (1.18 - 28.46) |

4.11 (0.37 -45.87) |

0.25 |

|

Laparotomy |

|||

|

No |

1 |

|

|

|

Yes |

0.03 (0 - 0.28) |

0.00 (0 - 51.67) |

0.06 |

Table 5: Prognostic factors predicting mortality.

LR-test= Likelihood Ratio test; OR= Odds Ratio; ORa = Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

DISCUSSION

From 2008 to 2017, out of 16,101 deliveries, the department recorded 138 uterine ruptures (about 1 uterine rupture per 117 deliveries). This high frequency could be due to late referrals towards the department, a poor prenatal care and a lack of labor monitoring due to an insufficiency of qualified personnel. Unlike developed countries where uterine rupture happens 2 to 3 times per 10,000 deliveries [15], it still frequently occurs in developing countries like Mali and other West African countries making the condition a major public health concern [14,16,17].

In general, uterine ruptures occur in relatively young patients aged 26 to 35 years [Table 1]. However, more uterine ruptures (61.3%) [Table 3] were recorded in patients with healthy uteri than in the literature where it occurs mainly on scarred uteri [4,18,19]. This could be explained by an inappropriate practice of obstetrical maneuvers by health professionals [16], a misuse of oxytocic [20], and a delay or mechanical dystocia mismanagement [21]. This fact points out the need for health authorities to ensure a good basic training and a continuous refresher training of health professionals. Strategies aiming to improve access to qualified health services to address obstetric emergencies should be initiated [22].

Among the cases of uterine rupture, 62.3% had an unscarred uterus while 37.7% had a scarred one. In the current study, having a unscarred uterus seems to be a potential risk factor for uterine rupture. This may be due to the fact that patients who experienced uterus surgery are well aware of the dangers related to delivery. Most of these patients’ pregnancies are also cautiously followed-up by health workers. Other studies showed that ruptures are most often of traumatic or iatrogenic origin [20]. Patients with scarred uterus are cautiously managed in such a way to avoid complications like uterine rupture [23]. Therefore, health care providers have a significant role to avoid maternal death due to uterine rupture especially with women without scarred uterus [22].

Current study suggests that patients with severe anemia were more likely to die from uterine rupture than the non-anemic ones (Adjusted OR =20.08, 95% CI= [1.97 - 204.86], p=0.002). A similar observation was made by other authors in hospital setting in Ethiopia [24]. Indeed, anemia is a public health concern in developing countries and its consequences on maternal mortality have been well studied [25]. Anemia was the second leading cause of maternal mortality in a study in Niger [26]. Another study conducted in the three main hospitals in Dakar, Senegal, showed that bleeding was the second leading cause of maternal death, accountable for 32 out of the 152 maternal deaths recorded over a one-year period [27]. In Ethiopia, a study conducted by Ahmed et al., in 2018 made the same observations with 80.3% having anemia as the commonest complication [24]. This high mortality rate is due not only to a delay in providing care to patients, but also to the unavailability of blood in hospitals when needed [28-31].

CONCLUSION

These data show that uterine rupture remains common in our daily practice and is one of the main causes of maternal and perinatal mortality. It is a medico-surgical emergency. Associated risk factors were multiparity, oxytocin misuse and non-scarred uterine. A better screening of at-risk populations through quality ANCs (refocused ANCs), increased capacity of intensive care wards, early diagnosis and rapid referral if needed and adequate patient management will improve maternal-fetal prognosis.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research which is part of the routine activities was done without any financial assistance.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The authors did not seek approval from a research ethics committee and the patients. All the data come from routine data, thus ethical approval was not required in this situation. However, patient confidentiality has been guaranteed and the data will only be used for academic purposes.

REFERENCES

- Hofmeyr GJ, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM (2005) WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: The prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG 112: 1221-1228.

- Guillemeau J (1620) De la grossesse et accouchement des femmes. Abraham Pacard, Paris,

- Eze JN, Anozie OB, Lawani OL, Ndukwe EO, Agwu UM, et al. (2007) Evaluation of obstetricians’ surgical decision making in the management of uterine rupture. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17: 179.

- Turgut A, Ozler A, Siddik Evsen M, Ender Soydinc H, Yaman Goruk N, et al. (2013) Uterine rupture revisited: Predisposing factors, clinical features, management and outcomes from a tertiary care center in Turkey. Pak J Med Sci 29: 753-757.

- You SH, Chang YL, Yen CF (2018) Rupture of the scarred and unscarred gravid uterus: Outcomes and risk factors analysis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 57: 248-254.

- Kaczmarczyk M, Sparén P, Terry P, Cnattingius S (2007) Risk factors for uterine rupture and neonatal consequences of uterine rupture: A population-based study of successive pregnancies in Sweden. BJOG 114: 1208-1214.

- Al-Zirqi I, Stray-Pedersen B, Forsén L, Daltveit AK, Vangen S (2016) Uterine rupture: Trends over 40 years. BJOG 123: 780-787.

- Guèye M, Mbaye M, Ndiaye-Guèye MD, Kane-Guèye SM, Diouf AA, et al. (2012) Spontaneous Uterine Rupture of an Unscarred Uterus before Labour. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology 598356: 1-3.

- Suner S, Jagminas L, Peipert JF, Linakis J (1996) Fatal spontaneous rupture of a gravid uterus: Case report and literature review of uterine rupture. J Emerg Med 14: 181-185.

- Body G, Boog G, Collet M, Fournié A, Grall JY, et al. (2005) Les urgences en gynécologie obstétriq Les 6 CHRU de la Région Ouest.

- Gibbins KJ, Weber T, Holmgren CM, Porter TF, Varner MW, et al. (2015) Maternal and fetal morbidity associated with uterine rupture of the unscarred uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213: 382.

- Ould El Joud D, Prual A, Vangeenderhuysen C, Bouvier-Colle MH (2002) Epidemiological features of uterine rupture in West Africa (MOMA Study). Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 16: 108-114.

- Dolo A, Keita B, Diabate FS, Maiga B (1990) [Uterine rupture during labor. Apropos of 21 cases observed at the gynecology-obstetric department of the National Hospital of Point-G]. Dakar Med 35: 61-64.

- Delafield R, Pirkle CM, Dumont A (2018) Predictors of uterine rupture in a large sample of women in Senegal and Mali: Cross-sectional analysis of QUARITE trial data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18: 432.

- Vandenberghe G, Bloemenkamp K, Berlage S, Colmorn L, Deneux-Tharaux C, et al. (2019) The International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems study of uterine rupture: A descriptive multi-country population-based study. BJOG 126: 370-381.

- Witter S, Boukhalfa C, Cresswell JA, Daou Z, Filippi V, et al. (2016) Cost and impact of policies to remove and reduce fees for obstetric care in Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali and Morocco. Int J Equity Health 15: 123.

- Prual A, Bouvier-Colle M-H, de Bernis L, Bréart G (2000) Severe maternal morbidity from direct obstetric causes in West Africa: Incidence and case fatality rates. Bull World Health Organ 78: 593-602.

- Ofir K, Sheiner E, Levy A, Katz M, Mazor M (2004) Uterine rupture: Differences between a scarred and an unscarred uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191: 425-429.

- Rameez MFM, Goonewardene M (2012) Uterine rupture. Obstet Intrapartum Emergencies: A Practical Guide to Management. Pg no: 52-588.

- Vernekar M, Rajib R (2016) Unscarred Uterine Rupture: A Retrospective Analysis. J Obstet Gynecol India 66: 51-54.

- Turner MJ (2002) Uterine rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 16: 69-79.

- Igwegbe AO, Eleje GU, Udegbunam OI (2013) Risk factors and perinatal outcome of uterine rupture in a low-resource setting. Niger Med J 54: 415-459.

- Smith JG, Mertz HL, Merrill DC (2008) Identifying risk factors for uterine rupture. Clin Perinatol 35: 85-99.

- Ahmed DM, Mengistu TS, Endalamaw AG (2018) Incidence and factors associated with outcomes of uterine rupture among women delivered at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: Cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18: 447.

- Motomura K, Ganchimeg T, Nagata C, Ota E, Vogel JP, et al. (2017) Incidence and outcomes of uterine rupture among women with prior caesarean section: WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. Sci Rep 7: 44093.

- Alkassoum I, Djibo I, Hama Y, Abdoulwahabou AM, Amadou O (2018) Risk factors for in-hospital maternal mortality in the region of Maradi, Niger (2008-2010: A retrospective study of 7 regional maternity units. Med Sante Trop 28: 86-91.

- Garenne M, Mbaye K, Bah MD, Correa P (1997) Risk factors for maternal mortality: A case-control study in Dakar hospitals (Senegal). Afr J Reprod Health 1: 14-24.

- Getahun WT, Solomon AA, Kassie FY, Kasaye HK, Denekew HT (2018) Uterine rupture among mothers admitted for obstetrics care and associated factors in referral hospitals of Amhara regional state, institution-based cross-sectional study, Northern Ethiopia, 2013-2017. PLoS One 13: 0208470.

- Orji EO, Fasubaa OB, Onwudiegwu U, Dare FO, Ogunniyi SO (2002) Decision-intervention interval in ruptured uteri in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. East Afr Med J 79: 496-498.

- Arsenault C, Fournier P, Philibert A, Sissoko K, Coulibaly A, et al. (2013) Atención obstétrica de urgencia en Malí: Gastos catastróficos y sus efectos empobrecedores en los hogares. Boletín de la Organización Mundial de la Salud 91: 157-236.

- Ndour C, Gbété DS, Bru N, Abrahamowicz M, Fauconnier A, et al. (2013) Predicting In-Hospital Maternal Mortality in Senegal and Mali. PLoS One 8: 64157.

Citation: Sima M, Traoré MS, Kanté I, Coulibaly A, Koné K, et al. (2020) Therapeutic, Clinical and Prognostic Aspects of Uterine Rupture in the Point G Teaching Hospital, Bamako, Mali. J Reprod Med Gynecol Obstet 5: 037.

Copyright: © 2020 Mamadou Sima, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.