Three Trends Shaping the Politics of Aging in America: An Update

*Corresponding Author(s):

Nora SuperCenter For The Future Of Aging, Milken Institute, 730 15th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20005, United States

Tel:+1 2023366408,

Email:nsuper@milkeninstitute.org

Abstract

Gerontologists have long studied the social, economic, and health implications of populations, but they often do not consider the political implications. This current opinion commentary updates an article written in early 2020 that identified three converging trends that would shape U.S. politics for the next decade. In this article, I reflect on how the election of Joe Biden as the U.S. president and the COVID-19 pandemic have altered these trends.

Keywords

Aging; Caregiving; Long-term care; Medicare; Migration; Social Security

Introduction

In early 2020, the Gerontological Society of America published my article that outlined three converging trends that I predicted would shape U.S. politics for decades to come [1]. Since that time, much has happened to change the political landscape. The global pandemic and the election of President Joe Biden have fundamentally altered my predicted course. This commentary updates the trends and considers the political implications for policies impacting older adults in light of these major events.

Material And Methods

This commentary is based on an analysis of new U.S. federal legislation, policies, budget documents, and published research that tracks changes in life expectancy, employment, housing, living and spending patterns.

Trend 1: Two-thirds of the U.S. federal budget will be consumed by social security and medicare

In my original article, I cited Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections showing that Social Security and Medicare will account for about two-thirds of mandatory, non-defense federal spending by 2029 in the U.S. [2]. This rise in spending relates mainly to the fact that the U.S. population age 65 and older has more than doubled over the past 50 years and will reach nearly 20 percent by 2029. Escalating health care costs (in both the public and private sectors) also push Medicare spending higher, and the pandemic and related illnesses have exacerbated this trend.

Social Security reform stalls: In the past, the U.S. Congress and President have put forward comprehensive proposals to improve the solvency of the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds. The most recent Social Security Trustees report projected that the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund will be depleted in 2034 [3]. But Social Security reform has not been taken on as a major national issue since President George W. Bush put forward an initiative in 2005 that would have reduced spending by partially privatizing the system. This initiative was fiercely opposed by AARP and other influential lobbying organizations and caused the presidents following Bush to trod lightly on Social Security.

President Donald Trump reversed the course of past Republican administrations by essentially declaring Social Security and Medicare off-limits for benefit and spending reductions. President Biden campaigned on reforming Social Security, including benefit increases and payroll taxes for those earning $400,000 and up. As I noted in my earlier article, proposals to increase the wage cap to $400,000 (currently at $142,800) and increase taxes on the wealthy are politically popular among congressional Democrats.

In his 2022 budget proposal, Biden failed to include any major changes to Social Security. However, he did propose a 9.7 percent increase, or $1.3 billion, in funding to the Social Security Administration (SSA) to improve services. SSA’s operating budget fell by 13 percent in inflation-adjusted terms between 2010 and 2021, while the number of Social Security beneficiaries rose by 22 percent [4]. Republican lawmakers put forward an alternative budget in May 2021 that would, among other provisions, raise the age at which one receives full Social Security benefits to age 69 by 2030. Currently, the age is scheduled to rise to 67 by 2022 [5]. If enacted, these increases would likely keep many older Americans working for more years than they expect. These types of changes (e.g., increases in age of eligibility and benefit reductions) are unpopular with voters from both parties, hence it is unlikely they will be enacted any time soon.

Medicare expansion and cost growth continue: The Medicare Trustees projected last year that the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund will become insolvent in 2024-just three years from now. CBO forecasts a 2026 insolvency date, and it’s unclear what the economic outlook will be due to increasing rates of COVID-19 infections as of this writing. Medicare was the largest single purchaser of personal health care in 2018, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary [6]. This trend in upward spending is likely to continue as the number of beneficiaries and costs of services and treatments continue to grow.

Biden’s budget plan would add a new dental, vision, and hearing benefit to Medicare. He plans to pay for these expansions by reducing prescription drug costs. It remains to be seen whether any of his budget priorities related to Social Security and Medicare will be passed by Congress, where Democrats hold a narrow majority in the House and a 50-50 split in the Senate. To pay for his overall budget, which is estimated to cost $6 trillion, Biden plans to increase taxes on corporations and high-income individuals [7]. The Democrats have vowed to enact these changes under reconciliation rules, which do not require a majority vote.

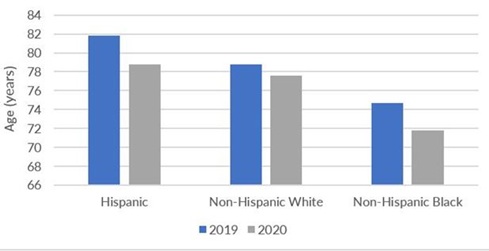

COVID-19 also revealed deep racial and ethnic inequities in access to health care. Sadly, overall life expectancy from 2019 to 2020 saw the steepest decline in the U.S. since World War II, according to the National Center for Health Statistics [8] (Figure 1). Overall, life expectancy fell by a year and a half. Hispanic Americans experienced the most significant decline in life expectancy-three years-and Black Americans experienced a decrease of 2.9 years. White Americans lost 1.2 years in life expectancy. The pandemic largely caused this precipitous drop in 2020, and researchers predict it will likely not be permanent [9]. However, they expect the effects of the pandemic on life expectancy, especially for Black and Latino populations, could last for years. The death of George Floyd brought protests across the nation and reignited interest and awareness of the Black Lives Matter movement. On top of this, the higher death rates from COVID among Black and Latino populations brought new attention to the historical inequities that these populations have endured in both health and financial wellness. Because Medicare and Social Security provide a vital safety net to low-income population of all races, I believe that we won’t see major reductions in spending on either of these programs for many years to come. The question is how this increased spending might crowd out spending for other national priorities such as education, defense and the environment.

Figure 1: Life expectancy at birth, by race: United States, 2019 and 2020.

Figure 1: Life expectancy at birth, by race: United States, 2019 and 2020.

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2020

Trend 2: The number of caregivers is shrinking as the need for care explodes

In my original article, I highlighted the long-term trend of the demand for caregivers outstripping supply. Again, the pandemic exacerbated this problem, devastatingly impacting both unpaid family caregivers and paid Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) workers. One silver lining of the pandemic may be the long-overdue recognition of the importance of both unpaid and paid caregivers for older adults with functional and cognitive limitations.

Paid leave for family caregiver’s gains momentum: As noted in my earlier article, changes in family size, composition and location have put increased strains on family caregivers. Because those over the age of 65 were deemed at high risk for becoming infected by COVID-19, thousands of older adults were forced to remain isolated within their homes and unable to get their groceries or have assistance with activities of daily living. As a result, family members were often called to care for these older adults by providing food, housekeeping and other assistance. On top of this, most children were not permitted to go to school during the height of the pandemic, forcing many workers to stay home to care for their children as they also juggled caregiving duties for aging relatives.

According to AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving, an estimated 29.2 million Americans are employed while caring for an aging family member [10]. On average, they work 35.7 hours per week in paid employment while providing about 24 hours of unpaid care each week [11]. Caregiving responsibilities-for both children and other family members-substantially impacted the workforce during the pandemic. A Bipartisan Policy Center survey found that caregiving was a factor for over 10 million adults who stopped working during COVID 19, and over three million who left the labor force entirely. Black adults were three times as likely (22 percent) as white adults (7 percent) to cite caregiving for other family members or relatives as a reason they stopped working [12].

More employers have begun to provide support for their employees who have caregiving responsibilities. For example, 39 percent of caregivers now have workplace benefits such as paid family leave, up from 32 percent in 2015 [10]. But the U.S. Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) only guarantees unpaid leave to 60 percent of the current American workforce. As a result, many employed caregivers do not take time off to care for family members because they cannot afford it. The lack of universal paid family leave especially impacts Black and Latina women, who disproportionately work in some of the hardest-hit sectors of the pandemic and are less likely to have access to flexible hours, paid leave, and the ability to work from home [13]. In a report released earlier this year by the Milken Institute Alliance to Improve Dementia Care, we recommended the passage of bipartisan federal and state efforts to expand paid family leave for elder care [14]. We believe this is a vital step toward health and economic equity, and without it, women and people of color may be forced out of the workforce to care for their families.

Biden’s American Families Plan proposes to phase in, over 10 years, 12 weeks of federal paid leave for most workers, including those caring for their own or a loved one’s serious illness [15]. The program would provide most workers-including the self-employed, part-time, and contract workers-a minimum of two-thirds of weekly wages or salary, up to $4,000 a month. The benefit would be government-funded and coordinated with existing state and employer-provided paid leave. So far, Republicans have not supported efforts to provide tax credits for child care and expand family paid leave, primarily because of the tax increases that would be necessary to pay for them.

New support for the LTSS workforce and a trend toward care at home: In my earlier article, I noted the considerable shortage of direct care workers available to provide LTSS to the growing aging population. A study in 2018 projected that by 2030, the U.S. will need an estimated 3.4 million direct care workers, a 1.1 million increase from 2015 [16]. These jobs have long lacked good pay, advancement, and training opportunities, and the COVID-19 virus has made it substantially more dangerous for these workers, with many long-term care workers dying or becoming ill.

The Global Council on Aging, in collaboration with Home Instead, released a study in 2021 examining the current state of the global caregiving workforce [17]. The report recommends several actions to build workforce capacity, including:

- Changing the perception of the caregiving profession

- Bolstering training and education standards

- Supporting and rewarding professional caregivers commensurate with the demands of the job and the value they provide

- Fully integrating the home care workforce into the health and social care ecosystem

People living (and working) in LTC facilities, nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living facilities accounted for 34 percent of COVID-19 deaths across the country by year-end 2020 [18]. And the industry already experienced extreme turnover, with one recent study showing the average annual turnover rate was 128 percent, with some facilities experiencing turnover that exceeded 300 percent [19]. Recognizing the growing importance of the caring economy on employers and employees, at the end of March 2021, President Biden announced the American Jobs Plan, which includes $400 billion to expand access to Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) for eligible seniors and people with disabilities and strengthen caregiving jobs [20]. The Better Care Better Jobs Act introduced by Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA) and Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-MI) would build on the $12.7 billion in HCBS funding that passed as part of the American Rescue Plan Act and carry forward President Biden’s infrastructure proposal to expand HCBS and strengthen the HCBS workforce [21].

However, these provisions were taken out of the bipartisan infrastructure bill as many Republicans argued that the caregiving workforce does not qualify as infrastructure and the price tag is too high. Democrats have vowed to include it in a fast-track process known as budget reconciliation, which will require all 50 votes from 48 Democrats and 2 Independents to pass. It remains to be seen if Senate leaders can keep their majority on board as the legislation evolves. Similarly, provisions from the American Families Plan could be part of one massive reconciliation bill either this year or next. In any case, the rapid expansion of telehealth and data supporting home-based and alternative care delivery models have increased demand for virtual care. I expect efforts to move health care and LTSS out of facilities and into the home to continue gaining momentum over the next several years as the aging population and the costs of care increase.

Trend 3: Migration trends may change as a result of covid-19

In my earlier article, I noted the geographic concentration of Americans age 65 and over in 10 states. California, Florida, and Texas lead the pack with one-quarter of all people age 65 living in one of these states [22]. I also noted that older adults tend to live in the rural Midwest and New England [23]. While it’s too soon to tell, this trend could change as the pandemic caused both young and older populations to migrate out of cities. As the risk of infection caused many employers to allow employees to work remotely, and it’s unclear if these new policies will remain in place post-pandemic. According to a recent Gallup poll, between October 2020 and April 2021, 52 percent of all workers have performed their job all or part of the time from home [24]. As a result, many people have decided to live in less expensive areas and/or away from heavily populated cities. A July 2020 Pew research study found that roughly one in five Americans either relocated due to the pandemic or know someone who has. Some of this migration includes young adults seeking a safe haven by living with other family members [25].

It is yet to be determined how permanent any of these pandemic-related migration patterns might turn out to be. In the long run, the widespread adoption of a vaccine could stall migration rates. Additionally, increased telecommuting may reduce employment-related migration.

Younger adults were more likely to move during the pandemic: In March 2020, software company Qualtrics surveyed 4,000 employed individuals across the United States, the U.K., Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand over two weeks in March 2021 [26]. Younger workers were much more likely to say they’ve moved away from their physical office locations than older workers, which the authors claim is due to fewer responsibilities and less job security:

- 25 percent of Gen-Zers reported moving away during the pandemic

- 16 percent of millennials reported changing locations

- 9 percent of Gen X (born between 1965 and 1980) workers reported moving away

- 6 percent of baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) reported moving

The growing aging population and changing housing preferences of younger generations do not bode well for older adults. Researchers predict seniors will end up selling their houses for much less than they hope [27], largely because aging baby boomers exiting the housing market will greatly outnumber younger purchasers. For example, the number of older homeowners who exit homeownership between 2026 and 2036 is projected to be between 13.1 million and 14.6 million, an increase of at least 42 percent over the previous decade [28].

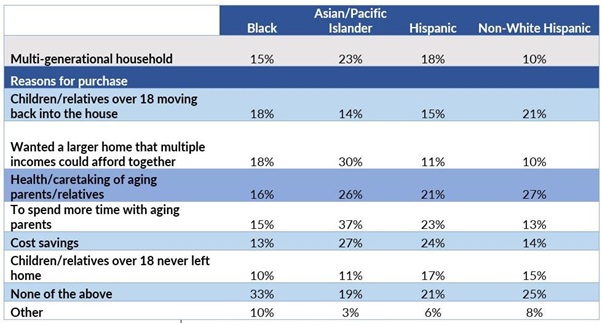

Multigenerational living increasing: COVID has accelerated interest in multigenerational living-with varying drivers across socioeconomic and cultural lines. The high cost of housing, student debt, and tighter credit rules nearly doubled the percentage of non married young adults living with their parents from 2000 to 2017, increasing from 12 percent to 22 percent [29]. More recently, buyers have focused on moving their aging parents to live with them. A recent analysis by the National Association of Realtors (NAR) (Figure 2) found that buyers purchasing multigenerational homes during the pandemic rose to a high of 15 percent. Before the pandemic, buyers of multigenerational homes cited both adult children coming back home and aging parents as reasons for the purchase. Now the number one reason is caretaking of aging parents/relatives [30].

Figure 2: Purchased Multigenerational Home By Race, 2020.

Figure 2: Purchased Multigenerational Home By Race, 2020.

Source: National Association of Realtors, 2021

Multigenerational living is more common among some minority populations than Whites. According to NAR, its latest survey found that nearly one-quarter of Asian buyers purchased a multi-generational home in 2020, compared to 18 percent of Latinx, 15 percent of Black Americans and 10 percent of Whites. Multigenerational living has many advantages for both older and younger generations. Grandparents may provide child care, for example, or younger generations can assist their older relatives with activities of daily living (e.g., housekeeping, meal preparation). In the face of shrinking availability and rising costs, alternative housing models for unrelated adults are also emerging [31]. These models include co-housing, student matching (which matches older homeowners with students who want to rent spare rooms), and Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) or so-called granny units. To move forward with more multifamily options, urban areas will need to curtail the setback rules on these ADUs.

Conclusion

In summary, the trends noted in my original article seem likely to continue. However, lawmakers seemed less focused on the impact of increased spending on the federal deficit, at least for the time being. The caregiver shortage has been exacerbated during the pandemic and doesn’t seem likely to abate unless workers receive higher pay and more job security for the difficult jobs expected of them. Finally, the pandemic may have impacted migration trends, with an increase in multigenerational housing and a decrease in job-related migration. Meanwhile, the U.S. birthrates fell for the sixth year in a row in 2020, dispelling any predictions that the pandemic could ignite a second baby boom. Fertility rates also reached a record low in 2020, putting the U.S. even further below replacement levels [32]. The trends make it clear that population aging will be a dominant political theme for years to come.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Cara Levy and Caroline Servat of the Milken Institute for tremendous research assistance in preparation of this article. She also thanks Mac McDermott of the Milken Institute for his assistance in citing references.

References

- Super N (2020) Three trends shaping the politics of aging in America. Public Policy Aging Rep 30: 39-45.

- Congressional Budget Office (2019) The budget and economic outlook: 2019 to 2029. Congressional Budget Office, Washington, D.C., USA.

- S. Social Security Administration (2020) Summary: Actuarial status of the Social Security Trust Funds. SSA, Woodlawn, Maryland, USA.

- Reich D, Kogan R, Windham K (2021) Biden Budget Provides Good Starting Point for Fiscal Year 2022 Appropriations Bills. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Olsen H (2021) Opinion: The latest Republican budget is a revival of Paul Ryan-ism. The GOP will have to do better. The Washington Post, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (2020) A data book: Health care spending and the Medicare program. MedPAC, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Tankersley J (2021) Biden to Propose $6 Trillion Budget to Make U.S. More Competitive. New York Times, New York, USA.

- Arias E, Tejada-Vera B, Ahmadb F, Kochanek KD (2021) Provisional life expectancy estimates for 2020. National Vital Statistics System, USA.

- Bosman J, Kasakove S, Victor D (2021) U.S. life expectancy plunged in 2020, especially for Black and Hispanic Americans. New York Times, New York, USA.

- AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving (2020) Caregiving in the U.S. AARP and NAC, Washington, DC, USA.

- https://research.wou.edu/c.php?g=551307&p=3785494

- Gitis B (2021) Morning consult poll: Caregiving led adults out of the workforce during COVID-19 and paid family leave can help bring them back. Bipartisan Policy Center, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Bartel AP, Kim S, Nam J, Rossin-Slater M, Ruhm C, et al. (2019) Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: Evidence from four nationally representative datasets. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Ahuja R, Levy C (2021) Better brain health through equity: Addressing health and economic disparities in dementia for African Americans and Latinos. Milken Institute, California, USA.

- The White House (2021) Fact Sheet: The American Families Plan. The White House, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Health Resources and Services Administration (2018) Long-term services and supports: Direct care worker demand projections 2015-2030. HRSA, Maryland, USA.

- Global Coalition on Aging & Home Instead (2021) Building the caregiving workforce our aging world needs. Global Coalition on Aging & Home Instead, Nebraska, USA.

- Curiskis A, Kelly C, Kissane E, Oehler K (2021) What we know-and what we don’t know-about the impact of the pandemic on our most vulnerable community. The COVID Tracking Project, USA.

- Gandhi A, Yu H, Grabowski DC (2021) High nursing home staff turnover in nursing homes offers important quality information. Health Affairs, USA.

- The White House (2021) Fact sheet: The American jobs plan. Washington, D.C., USA.

- Senate Aging Committee (2021) Better care better jobs act: A historic investment in the care economy. Senate Aging Committee, USA.

- Himes CL, Kilduff L (2019) Which U.S. states have the oldest populations? Population Reference Bureau. Washington, D.C., USA.

- S. Census Bureau (2018) 2018 national and state population estimates. U.S. Census Bureau, Maryland, USA.

- Gallup (2021) Seven in 10 U.S. white-collar workers still working remotely. Gallup, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Cohn D (2020) About a fifth of U.S. adults moved due to COVID-19 or know someone who did. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Qualtrics (2021) The future of work in 2021: Perspectives on the next normal. Qualtrics, Utah, USA.

- Nelson AC (2020) The great senior short-sale or why policy inertia will short change millions of America's seniors. Journal of Comparative Urban Law and Policy 4: 1-57.

- Dowell M, Simmons P (2018) The coming exodus of older homeowners. Fannie Mae, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Choi JH, Zhu J, Goodman L (2019) Young adults living in parents’ basements. Urban Institute, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Lautz J (2021) Full house: the rise of multi-generational homes during COVID-19. National Association of Realtors, Illinois, USA.

- Servat C, Super N (2019) Age-forward cities for 2030. Milken Institute, California, USA.

- Hart A (2021) American Birth And Fertility Rates Plunge To All Time Lows During Covid Pandemic, CDC Says. Forbes, New Jersey, USA.

Citation: Super N (2021) Three Trends Shaping the Politics of Aging in America: An Update. J Gerontol Geriatr Med 7: 107.

Copyright: © 2021 Nora Super, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.