Tolerance and Acceptability of a Low-Calorie Paediatric Peptide Enteral Tube Formula: A Multicentre Trial in the United Kingdom

*Corresponding Author(s):

Clare Thornton-WoodPaediatric Dietitian, NHS And Freelance, United Kingdom

Tel:+44 7895096365,

Email:claretwdiet@gmail.com

Abstract

The prevalence of Cerebral Palsy (CP) children who require a low-calorie feed is between 8-15%. ESPGHAN working group recommend using a low-fat, low-calorie, high fibre, micronutrient replete formula for immobile Neurological Impaired children.

Children aged 1-11 years with neurological issues were recruited from UK National Health Service (NHS). Participants were given the new low-calorie enteral tube feed formula with fibre (Peptamen Junior 0.6 kcal/ml, Nestlé Health Science) over a 7-day period. Formula intake and gastro-intestinal tolerance was recorded.

Seven out of 9 completed the 7-day trial. One child withdrew from the study due to slight increase in flatulence (the child was previously on a non-fibre containing feed). One child suspended the feed on day 3 due to user error. The average daily formula intake was 1032mls (600-1300ml) for those completing the trial and tolerated 100% of the low-calorie formula. One child saw increase in stool frequency (usually type 6) from 2 to 4 times per day and a slight increase in flatulence and bloating; it was noted this child was also previously on a non-fibre containing feed and suggest a slow introduction of fibre containing formula in children who are sensitive could be beneficial.

The new low-calorie formula was well tolerated by the majority of participants. This formula could be useful to ensure full nutritional goals are met for those children with low energy needs.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of children with Cerebral Palsy (CP) in the UK is estimated to be 2.4 per 1000 children aged 3- 10 years [1]. As per the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines (ESPGHAN); The Evaluation and Treatment of Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children with Neurological Impairment suggested neurological impaired children using a wheelchair require 60- 70% of energy intake when compared to healthy children [2,3].

According to the NASPGHAN (North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition) medical position publication, the prevalence of CP children who are overweight is 8%-14% [3].

Overfeeding with enteral nutrition risks a shift from a negative to positive energy balance, resulting in fat accumulation [2]. An observational cross-sectional study (n=15) of Neurologically Impaired (NI) children receiving enteral nutrition found that when guided by growth charts for healthy children, nutrition needs may be overestimated, leading to accumulation of excess body fat instead of normal growth and weight gain [4].

Reducing the volume of a formula administered to children with NI requiring enteral nutrition who have reduced energy needs, to reduce the risk of overfeeding or excessive weight gain, puts the child at risk of macro-and micronutrient deficiencies [5].

The ESPGHAN (European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition) working group recommends using a low-fat, low-calorie, high fibre, micronutrient replete formula for maintenance of enteral tube feeding after nutritional rehabilitation in immobile NI children; it recommends trial of a whey-based formula in cases of gastroesophageal reflux, gagging and retching in children with NI [2].

Polymeric formulas such as casein-based formulas may be poorly tolerated by some NI children requiring enteral nutrition, mainly due to underlying gastrointestinal problems such as Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux (GOR) and vomiting [2]. Whey peptide-based formulas may be beneficial in children with poor feed tolerance because of delayed gastric emptying. In children with severe NI, whey peptide-based enteral formula has also been shown to significantly reduce acid GOR episodes, retching and gagging [2].

To address the nutritional needs of CP children with decreased energy needs, a nutritionally complete, low calorie tube feed formula was developed and trialled in exclusively tube-fed children.

METHOD

Study design and participants

This study was a multicentre tolerance and acceptability trial. Recruitment took place across three National Health Services (NHS) in the UK; Brighton and Sussex University Hospital NHS Trust, Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust. Study design followed the UK Advisory Committee on Borderline Substances (ACBS) criteria to support submission for prescription usage within the National Health Service (NHS).

All participants (n=9) were tube fed and recruited from NHS settings and under the care of a dietitian/doctor. Participants were given the new formula for 7 days, Peptamen® Junior 0.6kcal/ml (Nestlé Health Science) containing 2.3g protein per 100ml, 6.8g carbohydrate per 100ml, 0.8g fibre per 100ml and osmolarity 206mOsm/l*. The dietitian completed baseline forms for each child and collected demographics, weight at start and end of study, diagnosis of allergies, current Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, stool type, consistency and frequency (stool type was measured using the Bristol Stool Chart). Parents and caregivers were asked to record GI symptoms and amount of formula consumed for the 7-day trial period.

*Information based on Nestle Health Science Peptamen Junior 0.6 data card dated February 2020.

Inclusion criteria

Children aged >12months of age well established and stable on a peptide enteral formula with a medical history of NI were recruited. Written and informed consent and assent from parent or guardian was obtained.

Exclusion criteria

Children who had an inability to comply with the study protocol in the opinion of the investigator were excluded from the study. These included children with known food allergies to any ingredient in the formula or those with renal or hepatic impairment. Children were also excluded if they were involved in another interventional study within 2 weeks of this trial, had a change in current medication, or use of additional macro micronutrient supplements during the study period, unless clinically indicated and approved by the investigator.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Manchester-North West-Haydock Research Ethics Committee 18/NW/0412 and HRA approval by HRA and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The following primary and secondary outcomes were measured:

Primary outcomes:

• Diarrhoea, constipation, bloating, nausea, vomiting, burping, flatulence, regurgitation, abdominal pain or discomfort.

• Measure of participant compliance, volume prescribed each day vs how much volume taken

Secondary outcome:

• Recording of body weight (kg) at start and end of study and investigation of any trend in weight changes during the intervention period.

RESULTS

All participants (n=9; aged 1-11 years) had a neurological issue; majority had CP with a gross motor function IV, one child had Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome, another had hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy.

Children with CP have a complex medical history and recruitment can be challenging (Table 1). The recruitment numbers for this study are similar to other clinical trials including children with severe developmental delay [6,7].

|

Participant |

Gender (Male or Female) |

Medical Condition |

|

A |

M |

Undiagnosed neurological condition, GMFCS IV |

|

B |

F |

Four limb cerebral palsy, GMFCS IV, history of seizures |

|

C |

F |

Cerebral palsy, GMFCS IV |

|

D |

F |

Grade III Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy |

|

E |

F |

Aicardi -Goutières Syndrome, GMFCS IV |

|

F |

F |

Four limb motor disorder (GMFCS IV) |

|

G |

M |

Cerebral palsy, GMFCS IV |

|

H |

M |

Cerebral palsy, GMFCS IV |

|

I |

M |

Ex prem, Grade 3 intraventricular Haemorrhage, Cerebral palsy |

Table 1: Participants medical condition.

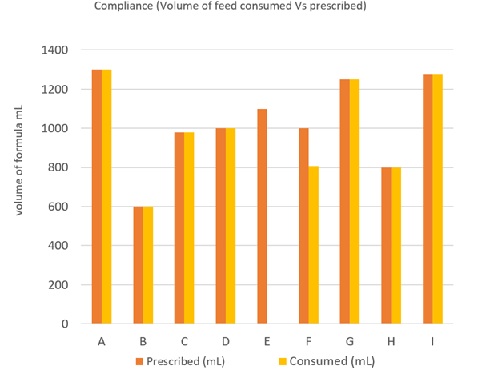

The average daily formula intake was 1032mL (600-1300mL) for those completing the trial (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Compliance-volume of feed taken versus prescribed.

Figure 1: Compliance-volume of feed taken versus prescribed.

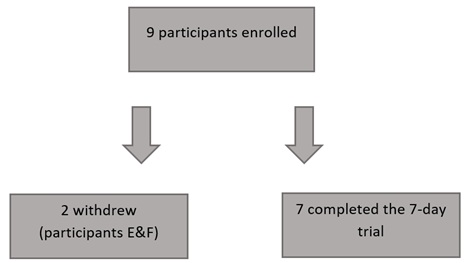

Nine children were recruited, seven completed the 7-day trial (Figure 2). One child did not complete the study; the child was withdrawn from the study as the caregiver noticed a slight increase in flatulence, this child was previously on a non-fibre containing feed. The other child suspended the feed on day 3 due to user error. All those who completed the trial tolerated 100% of the low-calorie formula. One child saw an increase in stool frequency (usually type 6) from 2 to 4 times per day and a slight increase in flatulence and bloating; it was noted this child was also previously on a non-fibre containing feed a slow introduction of fibre containing feed in children who are sensitive to fibre might be beneficial.

Figure 2: Participant completion summary.

Figure 2: Participant completion summary.

DISCUSSION

Children who are overweight and who are Neurologically Impaired are at the same risk of obesity as typically developing children with obesity and other co-morbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular, orthopaedic, neurological, hepatic, pulmonary, and renal disorders [8]. The study recruited nine children, who required a low-calorie formula to measure tolerance and acceptability. Of the nine children, seven completed the 7-day trial. Similar recruitment numbers have been observed in two clinical trials by Khoshoo et al, 1996 and Fried et al, 1992 [6,7]; as with these studies due to limited numbers of children requiring a low calorie peptide feed recruitment was challenging.

Khoshoo et al, 1996 recruited ten neurologically impaired children who were aged 4.5- 14.5 years and who were randomly crossed over to either a casein-based formula or a whey-based formula. The study found a significant reduction in the duration and episodes of gastroesophageal reflux with whey-based formulas (p < 0.05) [6]. Fried et al, 1992, recruited nine children aged 3- 18 years who experienced episodes of vomiting on a casein-based formula. This double-blind randomised controlled trial compared the effects of a casein and whey-based formula on gastric emptying times and episodes of vomiting. The study found reduction in episodes of vomiting in all children fed a whey-based formula (p< 0.05) [7].

Children with severe NI are a challenging group to study due to their ongoing changes in clinical condition and GI intolerances. In this study, we also found parents were very reluctant to change formula. Anecdotal feedback suggested some of the children were on complex feeding regimens and felt a short-term change may be seen as “disruptive”, despite the low-calorie formula providing sufficient amounts of vitamins and minerals and would therefore not require the use of top up feeds or extra vitamin and mineral supplementation.

There is no published data on the cost of obesity in children with NI, however the lifetime incremental medical costs of obesity in childhood has been estimated at US $19,000 or £14,520 (for an average child with obesity compared with a child of normal weight) [9].

The formula tested is a convenient ready to use complete formula that would prevent reduction of volumes or dilution of higher energy regular formula for patients with low energy needs.

A low-calorie formula may be a cost-effective solution for children with NI long-term. Future studies could focus on the long-term benefits of reducing the cost burden of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and comorbidities, as well as other patient-related outcome measures.

CONCLUSION

The new low-calorie formula was well tolerated by the majority of study participants. This formula could be useful to ensure full macro- and micronutrient goals are met for those children with low energy needs, as well as reducing the risks of overfeeding and developing other comorbidities.

Due to the small number of children requiring a low calorie peptide feed, recruitment was challenging; further studies with a higher sample size collected over a longer time frame could reinforce the evidence.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The study was funded by Nestlé Health Science UK.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Saduera is a Medical and Scientific Affairs Dietitian for Nestlé Health Science UK

C. Thornton-Wood received a consultancy payment from Nestlé Health Science

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the co-authors for their continued support and determination on completing the acceptability and tolerance study; Hayley Kuter at Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Liesl Silbernagl at Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust, Michelle Burke at Brighton & Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust.

REFERENCES

- Boyle CA, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Doernberg NS, Holmgreen P, Murphy CC, et al. (1996) Prevalence of Selected Developmental Disabilities in Children 3-10 Years of Age: The Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program, 1991. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 45: 1-14.

- Romano C, van Wynckel M, Hulst J, Broekaert I, Bronsky J, et al. (2017) European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children with Neurological Impairment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 65: 242-264.

- Marchand V, Motil KJ, NASPGHAN Committee on Nutrition (2006) Nutrition Support for Neurologically Impaired Children: A Clinical Report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 43: 123-135.

- Riley A, Vadeboncoeur C (2012) Nutritional differences in neurologically impaired children. Paediatr Child Health 17: 98-101.

- Vernon-Roberts A, Wells J, Grant H, Alder N, Vadamalayan B, et al. (2010) Gastrostomy feeding in cerebral palsy: enough and no more. Development & Child Neurology 52: 1099-1104.

- Khoshoo V, Zembo M, King A, Dhar M, Reifen R, et al. (1996) Incidence of gastroesophageal reflux with whey- and casein-based formulas in infants and in children with severe neurological impairment. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 22: 48-55.

- Fried MD, Khoshoo V, Secker DJ, Gilday DL, Ash JM, et al. (1992) Decrease in gastric emptying time and episodes of regurgitation in children with spastic quadriplegia fed a whey-based formula. J Pediatr 12: 569-572.

- Krebs NF, Jacobson MS, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition (2003) Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics 112: 424-430.

- Finkelstein EA, Graham WC, Malhotra R (2014) Lifetime direct medical costs of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 133: 854-862.

Citation: Thornton-Wood C, Saduera S (2020) Tolerance and Acceptability of a Low-Calorie Paediatric Peptide Enteral Tube Formula: A Multicentre Trial in the United Kingdom. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 7: 049.

Copyright: © 2020 Clare Thornton-Wood, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.