Tolerance and Acceptability of a New Paediatric Enteral Tube Feeding Formula Containing Ingredients Derived From Food: A Multicentre Trial in the United Kingdom

*Corresponding Author(s):

Clare Thornton-WoodPaediatric Dietitian, NHS And Freelance, United Kingdom

Tel:+44 7895096365,

Email:claretwdiet@gmail.com

Abstract

Recently, as reported by dietetic departments in the United Kingdom, we have seen an increase in Homemade Blended Diets (HBD) being given to children requiring tube feeding. HBD practice may increase the risk of tube occlusion and nutritional inadequacies. In 2015 the British Dietetic Association (BDA) developed their first ‘Practice toolkit liquidised food via gastrostomy tube’, which did not recommend administration of liquidised food via an enteral feeding tube. The BDA has recently updated its position statement, facilitating a more open discussion with patients and carers on blenderised diets and empowering dietitians to feel professionally supported.

A tube feed formula has been developed to address safety and nutritional inadequacies. Study design followed UK Advisory Committee on Borderline Substances (ACBS) criteria to support submission for prescription usage in the National Health Service (NHS). All participants (n=19) were tube fed, recruited from NHS settings and under the care of a dietitian/doctor. All were given the new formula for 7 days, Isosource Junior Mix, Nestlé Health Science. Demographic and medical data was obtained and gastrointestinal (GI) tolerance recorded; stool type was measured using the Bristol Stool Chart.

Participants (1-14 years) had a range of medical conditions. A number of participants reported positive changes in stools; including becoming firmer and decreasing in frequency. One child saw improved mood, eye contact and concentration. Resolution of reflux and a gradual decrease in retching were observed in 2 participants. One child experienced bloating and flatulence; they were previously on a tube feed without fibre which may have caused symptoms. There were no changes in weight during the study.

The new tube feed was well tolerated by the majority of participants; with a decrease in GI symptoms and beneficial changes in stool type.

INTRODUCTION

Homemade blended diets are becoming popular amongst caregivers and parents of children with long-term tube feeding [1]. Regular use of Homemade Blended Food (HBF) has been reported in the United States of America (USA) and parts of Europe for many years [2].

Two surveys conducted in 2015 and 2016 amongst paediatric registered dietitians revealed that Blenderised Tube Feeding (BTF) was used by 58 to 90 percent of their paediatric patients [3,4]. A cross-sectional study in adult patients indicated that 55% of patients had used BTF at some point during nutritional support [5].

More recently we have seen an increase in HBF practice by parents, as reported by dietetic departments in the United Kingdom [6]. In May 2015 the British Dietetic Association (BDA) developed their first ‘Practice toolkit on liquidised food via gastrostomy tube’, which did not recommend administration of liquidised food via an enteral feeding tube. If a parent, caregiver or patient decided to administer a liquidised diet via their feeding tube, a risk assessment was recommended [7]. The BDA has recently updated its position statement, facilitating a more open discussion with patients and carers on blenderised diets and empowering dietitians to feel professionally supported in the use of blended diets [6].

A number of studies and case reports have suggested positive changes when blended diets are introduced. A study in adult patients receiving home Enteral Nutrition (EN), BTF resulted in improved tolerance compared with commercial formulas with fewer patients reporting diarrhoea (6% vs 21%), constipation (3% vs 16%) and bloating (20% vs 37%) [5].

In a retrospective study, children who underwent fundoplication surgery and had symptoms of gagging and retching were given pureed food via a gastrostomy. The study found symptoms of gagging and retching were reduced by 76?100% in 52% of children, with 73% of children experiencing >50% decrease in symptoms. Case studies also revealed that patients experienced less reflux, constipation and better volume tolerance with BTF over commercial formulas (e.g. standard formulas or formulas containing fibre 100ml) [8,9].

However, a number of studies on the use of homemade tube feeds have been published and found:

- • A homemade BTF can lead to higher viscosity and may increase the risk of gastrostomy tube occlusion [1, 10].

- • Nutritional inadequacy in BTF has been observed and may lead to patients not meeting their nutritional needs [1,10-12].

- • A higher microbial load in commercial tube feed formula was identified in one study; although any effects on the patient group was not tested [12-13].

A study in the Philippines compared the viscosity of BTF prepared by four hospitals vs commercial powdered formulas; the mean viscosity (2,617 cps; range: 2.3? 45,060 cps) for all samples analysed (n=21) was more than 43 times higher than a typical commercial formula (60 cps) [1]. The same study assessed the nutrient content of the BTF; there was variability in macro`and micronutrients among samples (n=8) with the measured values tending to be lower than expected for all nutrients, with statistically significant differences for calories (p=0.023) [1].

Researchers in a Saudi Arabian study analysed the viscosity and osmolality of a BTF from three hospitals and found, compared with commercial formulas containing fibre and fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), all BTF samples were on average 200 times more viscous (mean viscosity: 2,276±4,292 vs 10.84±0.87) and had a higher mean osmolality (606.6 mOsm/kg H2O vs 277.9 mOsm/kg H2O) [10].

Two recent studies [14,15], tested a commercially available product with ingredients derived from real food [14,15]. Samela et al, noted improvements in stool consistency, from “large” and or “hard” to “soft” and or “formed” and stool frequency decreasing from 1-3 times a day to once a day. Ninety percent of intestinal failure children tolerated the feed at the prescribed volume when moving from an elemental formula to a commercial tube feed with ingredients derived from real food [14].

Schmidt et al, also found significant reduction in the number of watery stools (p<0.001) amongst critically ill neurological patients [15]. An observational study of 34 children who were transitioned to a BTF, reported reductions in gagging, retching vomiting and although a small number needed a gradual transition, the majority reported an immediate improvement in symptoms. Additionally, it was helpful in the transition to tube weaning [15].

Based on the literature discussed above, a study was devised to assess the tolerance and acceptability of a new tube feed formula in children over the age of 12 months; with the aim of providing a safer solution and to meet the emotional needs of parents who want their enterally-fed child to receive food ingredients and not compromising on the nutritional profile highlighted by Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) with homemade tube feeds.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This study was a multicentre tolerance and acceptability trial. Recruitment took place across five National Health Services (NHS) in the UK; Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London; Evelina Children’s Hospital, London; Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham; Sheffield Children’s Hospital, Sheffield; Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford. Study design followed the UK Advisory Committee on Borderline Substances (ACBS) criteria to support submission for prescription usage in the NHS.

All participants (n=19) were tube fed and recruited from NHS settings and were under the care of a dietitian doctor. Participants were given the new formula for 7 days, Isosource® Junior Mix 1.2kcal/ml (Nestlé Health Science) with 3.6g protein, 70g carbohydrate, 5g fibre, osmolarity 280mOsm/l, osmolality 340mOsm/kg and with 14% of food derived ingredients*. The dietitian completed baseline forms for each child and collected demographics, weight at start and end of study, diagnosis of allergies, current gastrointolerance (GI) symptoms, stool type, consistency and frequency (stool type was measured using the Bristol Stool Chart). Parents and caregivers were asked to record GI symptoms and amount of formula consumed for the 7-day trial period.

Inclusion criteria

Children aged 1-16 years of age who required a tube feed formula and taking >75% of energy needs from a feeding tube as part of their dietary management. Children aged >12months of age well established and stable on a standard feed or required to step down from a peptide enteral formula. Willingly given, written, informed consent and assent from patient or parent guardian was obtained.

Exclusion criteria

Children who had an inability to comply with the study protocol, in the opinion of the investigator, with known food allergies to any ingredient in the formula to with renal or hepatic impairment were excluded from the study. Children were excluded if involved in another interventional study within 2 weeks of this trial. Change in current medication or use of additional macro and micronutrient supplements during the study period, unless clinically indicated and prescribed by the investigator.

*Information from Nestle Health Science Isosource Junior Mix data card January 2020

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the London Hampstead Research Ethics Committee 18/LO/0546 and HRA approval by HRA and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW).

Primary outcome measures

- • Diarrhoea, constipation, bloating, nausea, vomiting, burping, flatulence, regurgitation, abdominal pain or discomfort.

- • Measure of participant compliance, volume prescribed each day versus how much volume of feed taken.

Secondary outcome measures

- • Recording of body weight (kg) at start and end of study and investigation of any trend in weight changes during the intervention period.

RESULTS

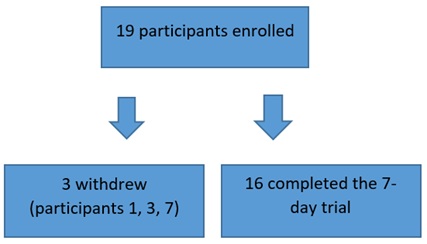

Participants (1-14 years) had a range of medical conditions, including global developmental delay, epilepsy, cerebral palsy and Down’s syndrome; 16/19 completed the 7-day trial (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of participants recruited, completed and withdrew.

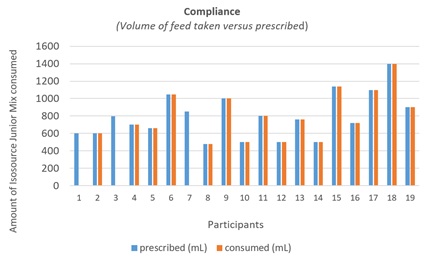

The average daily formula intake was 730mL (480-1400mL) for those completing the study (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Compliance-volume of feed (mL) taken versus prescribed (mL).

A number of participants reported positive changes in stool consistency; becoming firmer and decreasing in frequency. One child saw improved mood, eye contact and concentration. Resolution of reflux and gradual decrease in retching were observed in 2 participants. One child experienced bloating and flatulence; they were previously on a tube feed without fibre which may have caused symptoms. There were no weight changes during the study.

GI symptoms reported by caregivers in those completing the study were positive, except one case of constipation with flatulence. Two participants (4 and 6) experienced improvements in stool consistency such as decreased frequency and firmer consistency; in one this helped with the initiation of potty training.

Participant 8 usually experienced reflux after every feed; once the new formula was started the reflux resolved. There was also a change in stool frequency and consistency; with number of stools decreasing from 3 times a day to once a day and a change in consistency towards firmer stools (from type 6/7 to type 4). Participant 9 usually retched throughout the day; when the new formula was started there was a gradual decrease in retching through days 1 to 5.

Participant 2 experienced flatulence and constipation; the child received 20% of intake from food which is a confounding factor that may have caused symptoms. All remaining participants completed the 7-day trial in full and had no undesirable affects.

The reasons for withdrawal (n=3) were:

- • Participant 1 -Feed was not stored in the correct conditions, caused feed to thicken and carer stopped the trial.

- • Participant 3 -Stools began to move towards constipation.

- • Participant 7 -Became unwell, no further details as not specificed by healthcare professional or caregiver.

DISCUSSION

Clinical evidences on BTF are still limited, but according to the review by Weeks et al, 2019 [16], the emerging trends suggests that there are high levels of patient satisfaction with BTF, alleviation of gastrointestinal-related symptoms, and improved feeding tolerance, allowing for adequate growth and weight gain in medically complex patients.

However, in current practice BTF are highly variable and with inconsistent nutrient composition. It is therefore difficult to draw strong conclusions on the effect of blended diets. The nutritional value depends on recipes and the type of food used in the blended diet. Thus, providing a complete, well designed formula containing ingredients derived from food and with an adapted packaging set could be envisaged as a convenient and safe option for caregivers and parents.

In the present study, the Isosource® Junior Mix formula was well tolerated by the majority of those taking part and additionally there was resolution of a number of symptoms previously experienced by the participants such as decreased stool frequency, retching and in one, an observation of increased levels of alertness by carers. The symptom resolution was similar to that found in a number of other studies [2,14-15].

This was a small cohort study conducted over a short period of time and it is important to consider if the benefits could be sustained over a longer period of time. However, favourable results in the majority of the participants were seen in a short period of time. The study relied on parental recording of symptoms, however this was corroborated by additional information from carers; for instance, when greater eye contact and alertness was reported in one patient.

The child who presented with constipation was previously on a non-fibre containing feed and may have benefitted from a gradual changeover to the new feed.

There is emerging evidence that delivery of diverse whole foods may promote a healthy microbiome [17]. These observations require confirmation in dedicated studies for both BTF and commercial food-based formula.

CONCLUSION

The new tube feed containing ingredients derived from food was well tolerated by the majority of participants; it supported improved GI symptoms and beneficial changes in stool type in a number of participants. Based on the outcome of this study, we would recommend a change in the current policy documents and guidelines to allow the use of this new tube feed formula within the acute and community setting. Moreover, additional research is warranted to further document the health impact on GI symptoms, nutritional status, quality of life and to better understand the mechanisms underlying the benefits of food-based tube feed formula.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The study was funded by Nestlé Health Science UK.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Thornton-Wood received a consultancy payment from Nestlé Health Science UK

Saduera is a Medical and Scientific Affairs Dietitian for Nestlé Health Science UK

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Mohamed Mutalib at Evelina Children’s Hospital, Tara Kelly and Tamara Farrell at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation and Lisa Sheridan at Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust for help with recruitment for the study. We are grateful to the co-authors for their continued support and determination on completing the acceptability and tolerance study; Jackie Falconer at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation, Rita Shergill-Bonner at Evelina Children’s Hospital London, Haidee Norton at Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, Marie Watson at Sheffield Children’s Hospital Trust, Sheffield, Jayne Lewis, at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

REFERENCES

- Sullivan MM, Sorreda-Esguerra P, Platon MB, Castro CG, Chou NR, et al. (2004) Nutritional analysis of blenderized enteral diets in the Philippines. Asia Pac J Clin Nutrv13: 385-391.

- Thomas S (2017) Multi-agency practice for developing a blended diet for children fed via gastrostomy. Nurs Child Young People 29: 22-25.

- Epp L, Lammert L, Vallumsetla N, Hurt RT, Mundi MS (2017) Use of blenderized tube feeding in adult and pediatric home enteral nutrition patients. Nutr Clin Pract 32: 201-205.

- Johnson TW, Spurlock A, Pierce L (2015) Survey study assessing attitudes and experiences of pediatric registered dietitians regarding blended food by gastrostomy tube feeding. Nutr Clin Pract 30: 402-405.

- Hurt RT, Varayil JE, Epp LM, Pattinson AK, Lammert LM, et al. (2015) Blenderized tube feeding use in adulthome enteral nutrition patients: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Clin Pract 30: 824-829.

- The British Dietetic Association (2019) Policy Statement. The Use of Blended Diet with Enteral Feeding Tubes.

- The British Dietetic Association (2015) Practice Toolkit Liquidised Food via Gastrostomy Tube.

- Mortensen MJ (2006) Blenderized tube feeding clinical perspectives on homemade tube feeding. PNPG Post 17: 1-4.

- Novak P, Wilson KE, Ausderau K, Cullinane D (2009) The use of blenderized tube feedings. ICAN 1: 21-23.

- Mokhalalati JK, Druyan ME, Shott SB, Comer GM (2004) Microbial, nutritional and physical quality of commercial and hospital prepared tube feedings in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 25: 331-341.

- Vieira MMC, Santos VFN, Bottoni A, Morais TB (2018) Nutritional and microbiological quality of commercial and homemade blenderized whole food enteral diets for home-based enteral nutritional therapy in adults. Clinical Nutrition 37: 177-181.

- Santos VF, Morais TB (2010) Nutritional quality and osmolality of home-made enteral diets, and follow-up of growth of severely disabled children receiving home enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 56: 127-128.

- Pentiuk S, O’Flaherty T, Santoro K, Willging P, Kaul A (2011) Pureed by gastrostomy tube diet improves gagging and retching in children with fundoplication. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 35: 375-379.

- Samela K, Mokha J, Emerick K, Davidovics ZH (2017) Transition to a tube feeding formula with real food ingredients in pediatric patients with intestinal failure. Nutr Clin Pract 32: 277-281

- Schmidt SB, et al. (2018) The effect of a natural food based tube feeding in minimizing diarrhea in critically ill neurological patients. Clin Nutr 38: 332-340.

- Weeks C (2019) Home blenderized tube feeding: A practical guide for clinical practice. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 10:

- Gallagher K, Flint A, Mouzaki M, Carpenter A, Haliburton B, et al. (2018) Blenderized enteral nutrition diet study: Feasibility, clinical, and microbiome outcomes of providing blenderized feeds through a gastric tube in a medically complex pediatric population. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 42: 1046-1060.

Citation: Thornton-Wood C, Saduera S (2020) Tolerance and Acceptability of a New Paediatric Enteral Tube Feeding Formula Containing Ingredients Derived From Food: A Multicentre Trial (In The United Kingdom). J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 7: 050.

Copyright: © 2020 Clare Thornton-Wood, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.