Transcriptome of Homoeologous Genes Deduced from the Full-Length cDNA Clones of Common Wheat, Triticum aestivum L

*Corresponding Author(s):

Yasunari OgiharaKihara Institute For Biological Research, Yokohama City University, Yokohama, 244-0813, Japan

Tel:+81 458202435,

Fax:+81 458201901

Email:yogihara@yokohama-cu.ac.jp

Abstract

Allopolyploidization is an important event in plants, since it enhances heterosis and wide environmental adaptations. Common wheat, Triticum aestivum (AABBDD), arose through hybridization between T. turgidum (AABB) and Aegilops tauschii (DD) and subsequent whole genome duplication. To identify homoeologous genes expressed from the three distinct genomes of common wheat, we comprehensively surveyed available Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs), based on the proofed 26,241 full-length cDNA data. In total, 76,568 homoeologous genes were classified. These homoeologous genes were grouped into the 36,389 gene clusters, and assigned to each chromosome and/or chromosome arm of common wheat. Transcript specific homoeologous genes could be identified. In addition to protein coding genes, non-coding genes were located on chromosomes and/or chromosome arms. About half of the homoeologous genes acted as single copy genes, showing diploidization of these genes. Preferential gene expression from the B genome was found not only in single copy genes, but also in genes with multiple copies. Wheat specific genes were mostly in single copies, and expressed more from the B genome than the other genomes. GO classification showed that expressed genes have typical functions that characterize hexaploid wheat. This reference set of expressed genes in common wheat should be an indispensable genome resource.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Widespread occurrence of polyploidization (whole genome duplication) in plants provides evidence that it has advantages in development, adaptation and diversification [1-3]. Allopolyploidy resulting from interspecific or intergeneric hybridization and multiplication of more than two sets of genomes provides evolutionary advantages through speciation and environmental adaptation of higher plants, including many important crops [2,4-6]. At certain times, whole genome duplication has led to paleopolyploidy, showing structural genetic diploidization and subgenome fractionation (selective loss and retention of protein coding genes and non-coding RNA genes) leading to balance at the steady state of intergenomic orchestration [7-9]. These processes leading to allopolyploidization should bring about a broad range of genetic and epigenetic responses such as chromosome deletions, rearrangements, transpositions and epigenetic modifications [4,10- 20].

Common wheat, Triticum aestivum (2n = 6x = 42, genome formula AABBDD), formed through two additive allopolyploidizations. About 0.5 million years ago, the first allopolyploidization occurred by hybridization between the wild relatives Aegilops speltoides (2n = 2x = 14, SS?BB) and T. urartu (2n = 2x = 14, AA). Common wheat was spontaneously produced about 10,000 years ago from the second allopolyploidization between the early-cultivated allotetraploid T. turgidum ssp. dicoccum (2n = 4x = 28, AABB) and wild goat grass, Ae.tauschii ssp. strangulata (2n = 2x = 14, DD) followed by chromosome doubling of unreduced gametes [21-24]. Common wheat has been widely cultivated across the world, since it reveals more features of heterosis, such as growth vigor, environmental adaptability, and disease resistance than tetraploids [25]. Since there was a time lag between the two allopolyploidization events of common wheat, it should provide a model system to study genetic interactions among three genomes.

Orchestration of allopolyploid genomes after whole genome duplication leads to genome fractionation (unequal gene loss) as well as neo- and subfunctionalization of duplicated genes due to alternative nucleotide substitution rates. In addition to the biased fractionation of polyploid genomes, genes located on dominant genome regions have a tendency toward higher expression [26-28]. Actually, genomic asymmetry due to the non-random retention of controlling genes favoring one genome over others is manifested in allopolyploid wheat by the control of various genetic traits and syntenic genes [8,29]. Whole genome shotgun sequencing of Chinese Spring wheat showed that allohexaploid wheat lost 10,000 to 16,000 genes during the course of allohexaploidization [30]. Furthermore, reported accelerated alteration of homoeologous genes, such as nucleotide mutations and alternative splicing [31]. These structural changes of the common wheat genome are likely to occur during allotetraploidization, mainly because of the duration of the allopolyploid [32,33]. However, precise genome-wide data are required to show which homoeologous genes are expressed among the three genomes of common wheat for better understanding of gene regulation in allopolyploid. Hence, the present study is aimed to clarify transcriptome of homoeologous genes in common wheat, based on the full-length cDNA clones.

Here, we took advantage of the Full-Length (FL) cDNA sequence data of common wheat to complete reference set of its expressed homoeologous genes. We used all Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) of common wheat that had been cloned from cDNAs containing a poly(A)+ tail, and sequenced from both ends of the inserts. The full-length cDNAs which Cover The Coding Sequences (CDSs) or non-coding RNAs were proofed from these ESTs, including the CAP-trapped cDNAs, were classified into homoeologous genes expressed from the A, B and D genomes, and these homoeologous genes were grouped into gene clusters corresponding to those of the diploid [34]. Chromosome locations of these homoeologous genes were determined to show the subgenome fractionation of expressed genes [35].

RESULTS

Completion of Full-Length (FL) cDNA data of common wheat

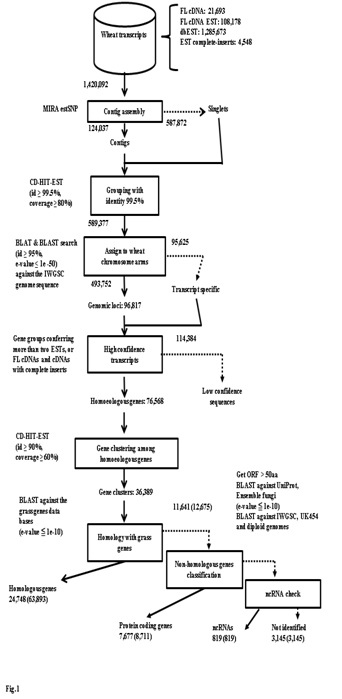

Furthermore, the cDNA clones of common wheat having certain gaps in the inserts and homology with cereal genes, rather than the 21,693 FL cDNA clones, were selected from the EST contigs. The nucleotide sequences of the resultant 4,548 cDNA clones harboring the complete CDS were determined. Finally, the 26,241 FL cDNA clones of common wheat were complete.

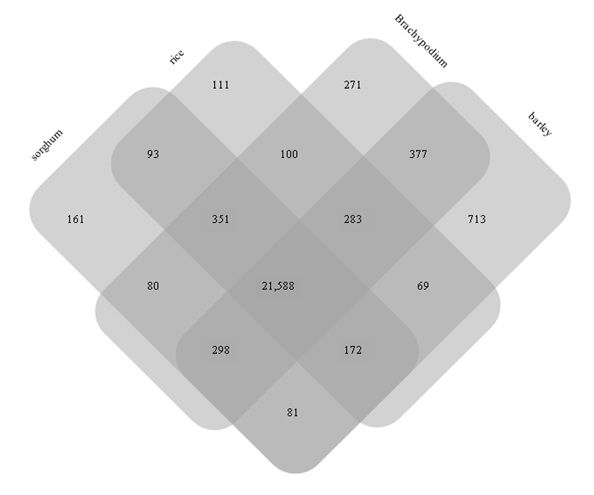

Figure 3: Number of wheat gene clusters homologous to grass genes.

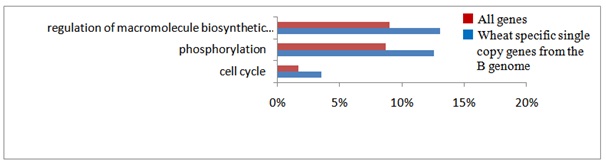

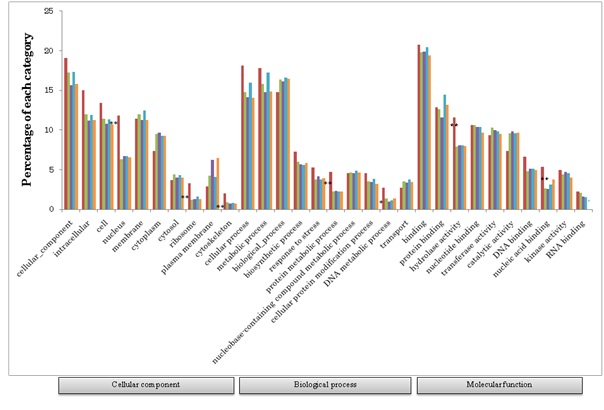

Figure 4: Gene ontology analysis of wheat specific genes.

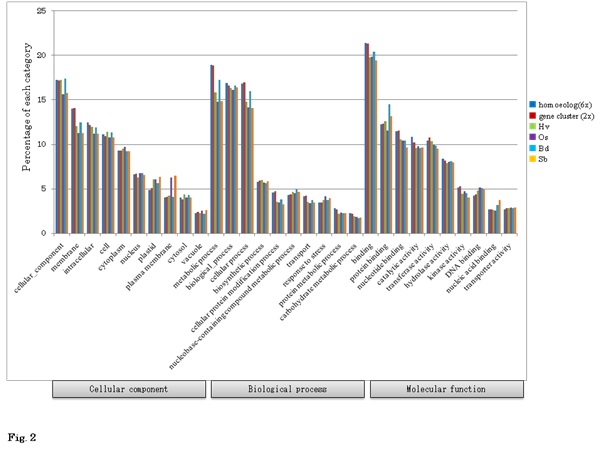

Gene ontology of gene clusters (? 2x_WhSp) was compared to that of barley (?Hv), rice (? Os), Brachypodium (? Bd), and Sorghum (? Sb). GO terms were categorized into three groups. Significant differences (χ2-test) are shown as * at the 5% level), and **at the 1% level). Subcategories are shown underneath the grouped GO terms.

|

|

Protein coding genes |

|

Non-coding genes |

|

|||

|

|

Homology with the grass genes |

Wheat specific gene |

Subtotal |

miRNA* |

ncRNA** |

Not identified |

Subtotal |

|

Assigned to the IWGSC genome sequence |

22,792 |

7,477 |

30,269 |

204 |

12 |

927 |

1,143 |

|

(61,452) |

(8,497) |

(69,949) |

|||||

|

Not assigned to the IWGSC genome sequence |

1,956 |

200 |

2,156 |

585 |

18 |

2,218 |

2,821 |

|

(2,441) |

(214) |

(2,655) |

|||||

|

Total |

24,748 |

7,677 |

32,425 |

789 |

30 |

3,145 |

3,964 |

|

(63,893) |

(8,711) |

(72,604) |

|||||

**: Non-coding RNAs were searched against NONCODE (http://www.noncode.org/download.php).

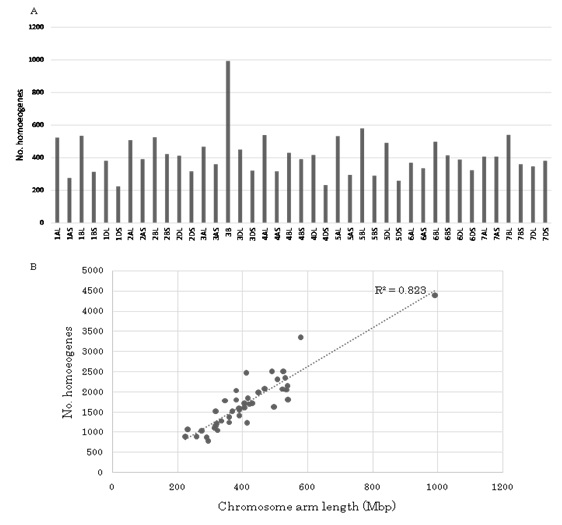

The chromosome assignments of 71,092 homoeologous genes are shown in figure 5A and B. Chromosome 3B harbored the most genes (4,399), while 6D contained the least (2,296). The average number of expressed genes per chromosome was 3,385. Although long arms of chromosomes tended to have more genes than short arms, 7AS (1,723) and 7DS (1,809) had more genes than 7AL (1,623) and 7DL (1,792). These chromosomes did not participate in the translocations observed in Chinese Spring wheat [36]. Since the DNA content of each chromosome arm and/or chromosome has been estimated, the number of expressed genes per Mbp on each chromosome and/or chromosome arm was calculated [37]. The average number of expressed genes per Mbp was 4.2. Although the overall expressed gene number was proportional to chromosome length for each chromosome (R2 = 0.8234: Figure 6B), two chromosome arms (2DL and 5BL) had a significantly higher than expected number at the 5% level (Figure 5), suggesting higher accumulation of expressed genes in those chromosome regions than others.

Figure 5: Chromosome assignment of wheat homoeogenes.

(A) Total of 71,092 homoeogenes was assigned to each chromosome and/or chromosome arm.

(B) The number of located homoeogenes correlated positively with the DNA content of chromosomes except for 2DL and 5BL.

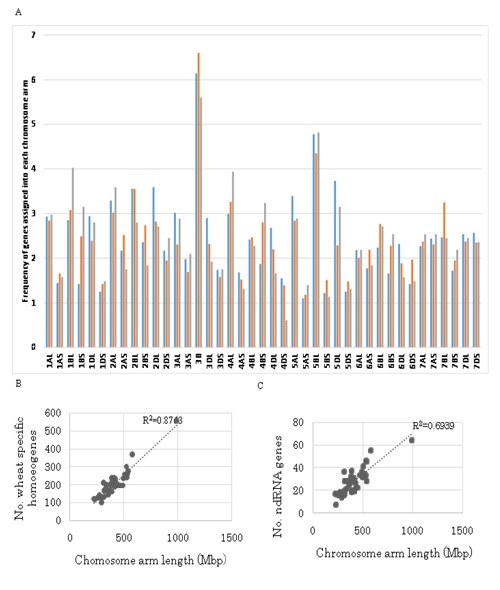

Figure 6: Chromosome assignment of characteristic genes.

Chromosome distribution of wheat specific (?) and non-coding RNA (?) homoeogenes were compared to the distribution of allhomoeogenes (?).

|

Expressed genomes |

No. expressed genes |

|||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4-6 |

7-12 |

>13 |

Total |

|

|

A |

4199 |

349 |

43 |

13 |

1 |

0 |

4605 |

|

|

B |

5236 |

410 |

85 |

35 |

2 |

0 |

5768 |

|

|

D |

4268 |

290 |

49 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

4613 |

|

|

Subtotal |

13703 |

1049 |

177 |

54 |

3 |

0 |

14986 |

|

|

(49.5) |

||||||||

|

A + B |

- |

1506 |

488 |

236 |

29 |

1 |

2260 |

|

|

A + D |

- |

1482 |

508 |

248 |

21 |

0 |

2259 |

|

|

B + D |

- |

1515 |

503 |

236 |

18 |

0 |

2272 |

|

|

Subtotal |

|

4503 |

1499 |

720 |

68 |

1 |

6791 |

|

|

(22.4) |

||||||||

|

A+B+D |

- |

- |

3951 |

3824 |

626 |

91 |

8492 |

|

|

(28.1) |

||||||||

|

Total |

13703 |

5552 |

5627 |

4598 |

697 |

92 |

30269 |

|

|

(45.3) |

(18.3) |

(18.6) |

(15.2) |

(2.3) |

(0.3) |

|||

Genes located in the B genome showed preferential expression over the other two genomes, A and D (P< 10-9, χ2 test). This preferential gene expression was found in single copy genes (P< 10-30, χ2 test) and multigenes having more than 7 copies (P< 10-5, χ2 test), but not in genes expressed from two genomes, i.e., when there was silencing of one genome (Table 2).

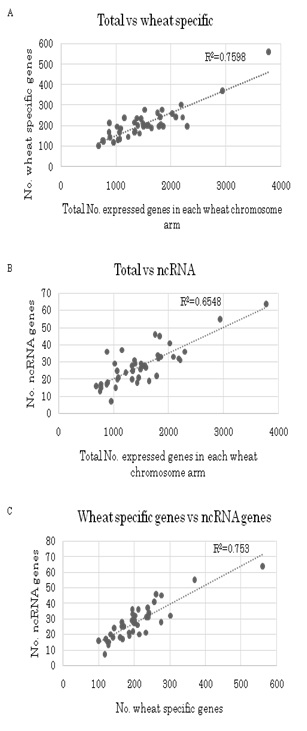

Expression of 7,477 wheat specific homoeologous genes from three distinct genomes was characterized. About 90% of these were transcribed as single genes from one of the three genomes (Table 1). However, 5% of homoeologous genes were not expressed in one of the three, and only 0.4% was expressed from all three genomes, suggesting a characteristic contribution of wheat specific genes. Preferential expression of the wheat specific genes by the B genome was found (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

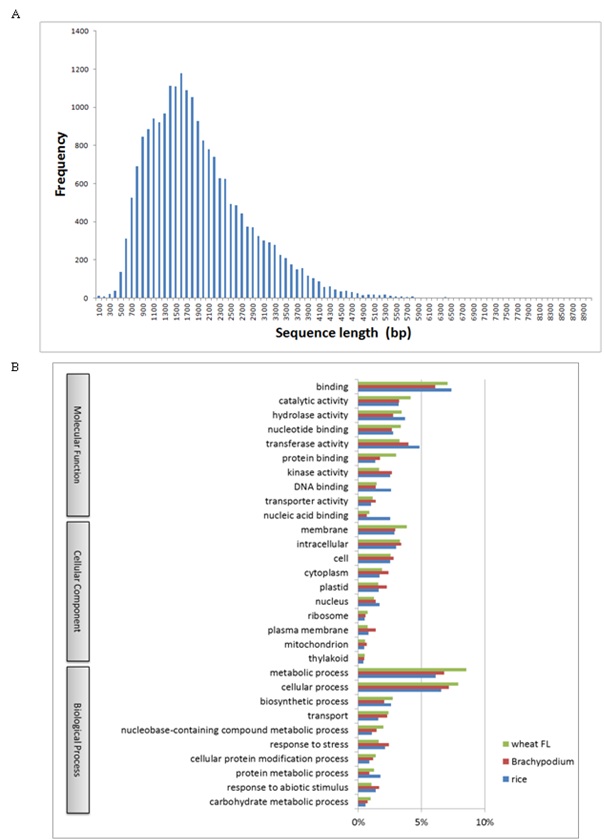

Reference set of transcripts is indispensable clues for gene prediction. Hence, we have completely surveyed expressed genes from various wheat tissues of common wheat grown under ordinary conditions and in biotic- and abiotic-stressed conditions, including CAP-trapped cDNAs (FL cDNAs;) [34]. Although collections of FL cDNAs are recognized as significant genetic resources, full-set surveys of FL cDNAs expressed from each genome of common wheat (allohexaploid: AABBDD) are not readily available. Therefore, we completed the sequencing of an additional 4,886 CAP-trapped FL cDNAs, so that 21,693 sequences for Chinese Spring wheat are now available. In addition to these CAP-trapped FL cDNAs, the inserts of 4,548 independent cDNA clones which cover the protein coding regions had been determined. Finally, the nucleotide sequences of the 26,241 FL-cDNA clones are available. This number is equivalent to those of Arabidopsis annotated from the genome (TAIR 10 https://www.arabidopsis.org/), suggesting that almost all expressed wheat genes containing poly-(A)+ tail can be captured with the cDNA clones (Figure S1) [40-43]. This is indispensable genome resource to predict the expressed genes in wheat.

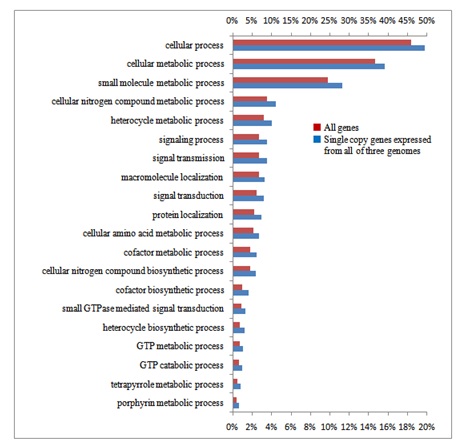

Based on these wheat FL cDNAs, all of the available wheat ESTs, including one-path sequences of CAP-trapped wheat cDNAs, were clustered. Finally, 76,568 homoeologously expressed genes (homoeologous genes) were identified (Figure 1). These classified expressed genes were clone-based and relatively abundant. The homoeologous genes were grouped to estimate the gene members of common wheat, designated as 36,389 gene clusters (Figure 1), of which 32,425 were protein coding genes (Table 1). This estimated gene number is equivalent to the gene number predicted from the genome sequences of diploid tetraploid, and hexaploid wheats [30,35,44-46]. Overall GO analysis of these homoeologous genes exhibited GO terms that were similar to grouped gene clusters of diploids and other cereal genes (Figure 2), suggesting that the list here of cDNA clones could survey almost all expressed genes in common wheat.

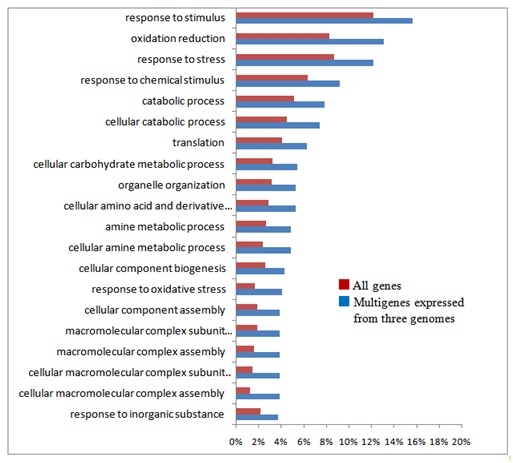

The A and B genomes of common wheat have a long history of co-existence, ca. 0.5 million years, before pollination with Ae. tauschii (DD) and genome-wide duplication about 10,000 years ago, giving rise to the allohexaploid [22,23,47]. Accumulation of genomics data in cereals enables characterization of the features of expression of the allohexaploid wheat genes located on the three distinct genomes [48-50]. Thus, orchestration of expressed homoeologous genes in natural hexaploid wheat at a steady level should be clarified. In this study, the number of expressed homoeologous genes in each gene cluster was estimated. About half of expressed genes in common wheat were expressed only from one of three genomes. While, a quarter of expressed genes used two genomes, and remaining a quarter were expressed from all three genomes (Table 2). On the other hand, almost all (ca. 95 %) wheat specific genes were transcribed from one genome (Research Data SF1A), suggesting characteristic feature of wheat specific genes. Preferential gene expression from the B genome was found for both single copy genes and multigene families (Table 2 and Research Data SF1B). This expression preference was also found in wheat specific genes (Table 1). Furthermore, significantly fewer wheat specific homoeologous genes were expressed as single copy genes by the D genome, while the number of wheat specific single copy genes assigned to the A and B genomes were not significantly different (Table 2 and Research Data SF1A and SF1B). These lines of evidence suggest both more negative regulation of the D genome for wheat specific genes and maternal effects on expression of homoeologous genes [33,51]. The observation that certain chromosome arms most of which were of the B genome, harbored more expressed homoeologous genes than expected (Figure 5 and Figure S2) suggests that gene regulation system (s) might operate on specific chromosome regions. Preferential transcription of genes from one progenitor genome has been reported in cotton, Arabidopsis and maize as well as in wheat [17,26,52-55].

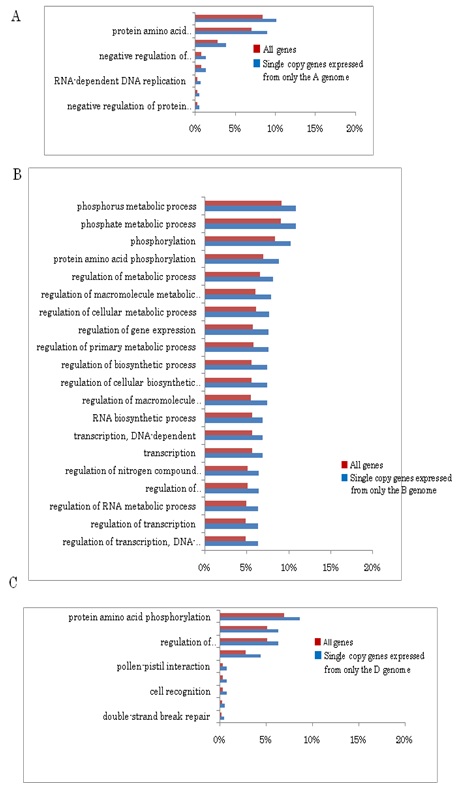

GO analysis revealed that single copy genes of common wheat play characteristic roles distinct from other categories of genes such as signal transduction and stress responses (Figure S3). In addition to the GO categories of single copy genes found in common among the three genomes, single copy genes of the B genome fell into further categories (Figure S3B). Categories of the genes expressed from two of the three genomes, and those expressed from each of the three genomes were concerned with basic metabolism (Figure S4). Moreover, multigenes expressed from all three genomes, among which genes of the B genome exhibited preferential expression, showed characteristic functional categories such as stress responses in addition to metabolic processes (Figure S5). These data suggest functional partitioning of respective homoeologous genes. Genetic alterations and epigenetic regulation are known to play roles in gene expression of polyploids [56]. Although substantial DNA loss especially from the A and B genomes, has been reported in common wheat, genetic alterations alone of allohexaploid wheat are unable to explain the observed expression profiles of homoeologous genes: the number of expressed homoeologous genes was similar for the A and D genomes, while more were found in homoeologous genes from the B genome (Tables 1 and 2) [8,12,30,57,58]. This suggests that the epigenetic regulation operating on the genes in each genome is substantial [59-62]. In fact, silencing of homoeologs through altered DNA methylation and repression of counterpart homoeologous genes with miRNAs and siRNAs plays important roles in control of expression of target genes [51,63,64].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Final collection of CAP-trapped cDNA sequences

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The work was supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Genomics for Agricultural Innovation, KGS1002). Most part of DNA sequencing had been carried out in RIKEN Center for Life Science Technologies, Division of Genomic Technologies and Genome Network Analysis Support Facility. Bioinformatic work was partly conducted on the supercomputer system, National Institute of Genetics (NIG), Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KM collected cDNA clones, designed images, carried out computational analyses and participated in manuscript writing. KK designed images and performed DNA sequencing of cDNA clones. YK performed computational analyses and developed DATA base. KM contributed to construct full-length cDNA libraries, sequence the full-length cDNA clones, and construct full-length cDNA data base of common wheat. HT, MT NS, JK developed new sequencing strategy of cDNA clones, carried out sequencing and computational analyses. YN and KN contributed in computational data analyses and construction of data base of wheat transcriptome. YO and JK designed the research, and wrote manuscript. All authors read and approve the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Leitch AR, Leitch IJ (2008) Genomic plasticity and the diversity of polyploid plants. Science 320: 481-483.

- Soltis PS, Soltis DE (2009) The role of hybridization in plant speciation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 561-588.

- Soltis DE, Visger CJ, Soltis PS (2014) The polyploidy revolution then…and now: Stebbins revisited. Am J Bot 101: 1057-1078.

- Wendel JF (2000) Genome evolution in polyploids. Plant Mol Biol 42: 225-249.

- Doyle JJ, Flagel LE, Paterson AH, Rapp RA, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, et al. (2008) Evolutionary genetics of genome merger and doubling in plants. Annu Rev Genet 42: 443-461.

- Renny-Byfield S, Wendel JF (2014) Doubling down on genomes: polyploidy and crop plants. Am J Bot 101: 1711-1725.

- Freeling M, Woodhouse MR, Subramaniam S, Turco G, Lisch D, et al. (2012) Fractionation mutagenesis and similar consequences of mechanisms removing dispensable or less-expressed DNA in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 131-139.

- Pont C, Murat F, Guizard S, Flores R, Foucrier S, Bidet Y, et al. (2013) Wheat syntenome unveils new evidences of contrasted evolutionary plasticity between paleo- and neoduplicated subgenomes. Plant J 76: 1030-1044.

- Roulin A, Auer PL, Libault M, Schlueter J, Farmer A (2013) The fate of duplicated genes in a polyploid plant genome. Plant J 73: 143-153.

- Pikaard CS (1999) Nucleolar dominance and silencing of transcription. Trends Plant Sci 4: 478-483.

- Comai L, Tyagi AP, Winter K, Holmes-Davis R, Reynolds SH, et al. (2000) Phenotypic instability and rapid gene silencing in newly formed arabidopsis allotetraploids. Plant Cell 12: 1551-1568.

- Ozkan H, Levy AA, Feldman M (2001) Allopolyploidy-induced rapid genome evolution in the wheat (Aegilops-Triticum) group. Plant Cell 13: 1735-1747.

- Kashkush K, Feldman M, Levy AA (2003) Transcriptional activation of retrotransposons alters the expression of adjacent genes in wheat. Nat Genet 33: 102-106.

- Adams KL, Cronn R, Percifield R, Wendel JF (2003) Genes duplicated by polyploidy show unequal contributions to the transcriptome and organ-specific reciprocal silencing. PNAS 100: 4649-4654.

- He P, Friebe BR, Gill BS, Zhou JM (2003) Allopolyploidy alters gene expression in the highly stable hexaploid wheat. Plant Mol Biol 52: 401-414.

- Osborn TC, Pires JC, Birchler JA, Auger DL, Chen ZJ, et al. (2003) Understanding mechanisms of novel gene expression in polyploids. Trends Genet 19: 141-147.

- Wang J, Tian L, Madlung A, Lee HS, Chen M, et al. (2004) Stochastic and epigenetic changes of gene expression in Arabidopsis polyploids. Genetics 167: 1961-1973.

- Buggs RJ, Zhang L, Miles N, Tate JA, Gao L, et al. (2011) Transcriptomic shock generates evolutionary novelty in a newly formed, natural allopolyploid plant. Curr Biol 21: 551-556.

- Ng DW, Lu J, Chen ZJ (2012) Big roles for small RNAs in polyploidy, hybrid vigor, and hybrid incompatibility. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 154-161.

- Shi X, Ng DW, Zhang C, Comai L, Ye W, et al. (2012) Cis- and trans-regulatory divergence between progenitor species determines gene-expression novelty in Arabidopsis Nat Commun 3: 950.

- Kihara H (1944) Discovery of the DD-analyser, one of the ancestors of Triticum vulgare. Agric Hortic 19: 13-14.

- Feuillet C, Langridge P, Waugh R (2008) Cereal breeding takes a walk on the wild side. Trends Genet 24: 24-32.

- Matsuoka Y (2011) Evolution of polyploid triticum wheats under cultivation: the role of domestication, natural hybridization and allopolyploid speciation in their diversification. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 750-764.

- Kihara H, Okamoto M, Ikegami M, Tabushi J, Suemoto H, et al. (1950) Morphology and fertility of five new synthesized hexaploid wheats. Seiken Ziho 4: 127-140.

- Dubcovsky J, Dvorak J (2007) Genome plasticity a key factor in the success of polyploid wheat under domestication. Science 316: 1862-1866.

- Schnable JC, Springer NM, Freeling M (2011) Differentiation of the maize subgenomes by genome dominance and both ancient and ongoing gene loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 4069-4074.

- Cheng F, Wu J, Fang L, Sun SL, Liu B, et al. (2012) Biased Gene Fractionation and Dominant Gene Expression among the Subgenomes of Brassica rapa. PLoS ONE 7: 36442.

- Garsmeur O, Schnable JC, Almeida A, Jourda C, D'Hont A, et al. (2014). Two evolutionarily distinct classes of paleopolyploidy. Mol Biol Evol 31: 448-454.

- Feldman M, Levy AA, Fahima T, Korol A (2012) Genomic asymmetry in allopolyploid plants: wheat as a model. J Exp Bot 63: 5045-5059.

- Brenchley R, Spannagl M, Pfeifer M, Barker GL, D’Amore R, et al. (2012) Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Nature 491: 705-710.

- Akhunov ED1, Sehgal S, Liang H, Wang S, Akhunova AR, et al. (2013) Comparative analysis of syntenic genes in grass genomes reveals accelerated rates of gene structure and coding sequence evolution in polyploid wheat. Plant Physiol 161: 252-265.

- Mestiri I, Chagué V, Tanguy AM, Huneau C, Huteau V, et al. (2010) Newly synthesized wheat allohexaploids display progenitor-dependent meiotic stability and aneuploidy but structural genomic additivity. New Phytol 186: 86-101.

- Zhang H, Zhu B, Qi B, Gou X, Dong Y, et al. (2014) Evolution of the BBAA component of bread wheat during its history at the allohexaploid level. Plant Cell 26: 2761-2766.

- Kawaura K, Mochida K, Enju A, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, et al. (2009) Assessment of adaptive evolution between wheat and rice as deduced from full-length common wheat cDNA sequence data and expression patterns. BMC Genomics 10: 271.

- International Wheat Genome Sequence Consortium (IWGSC) (2014) A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) genome. Science 345: 1251788.

- Devos KM, Dubcovsky J, Dvo?ák J, Chinoy CN, Gale MD (1995) Structural evolution of wheat chromosomes 4A, 5A, and 7B and its impact on recombination. Theor Appl Genet 91: 282-288.

- Safár J, Simková H, Kubaláková M, Cíhalíková J, Suchánková P, et al. (2010) Development of chromosome-specific BAC resources for genomics of bread wheat. Cytogenet Genome Res 129: 211-223.

- Mochida K, Yamazaki Y, Ogihara Y (2003) Discrimination of homoeologous gene expression in hexaploid wheat by SNP analysis of contigs grouped from a large number of expressed sequence tags. Mol Genet Genomics 270: 371-377.

- Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z (2010) agriGO: A GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 64-70.

- Rice Full-Length cDNA Consortium, National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences Rice Full-Length cDNA Project Team, Kikuchi S, Satoh K, Nagata T, et al. (2003) Collection, mapping, and annotation of over 28,000 cDNA clones from japonica rice. Science 301: 376-379.

- Soderlund C, Descour A, Kudrna D, Bomhoff M, Boyd L, et al. (2009) Sequencing, mapping, and analysis of 27,455 maize full-length cDNAs. PLOS Genet 5: 1000740.

- Matsumoto T, Tanaka T, Sakai H, Amano N, Kanamori H, et al. (2011) Comprehensive sequence analysis of 24,783 barley full-length cDNAs derived from 12 clone libraries. Plant Physiol 156: 20-28.

- Mochida K, Uehara-Yamaguchi Y, Takahashi F, Yoshida T, Sakurai T, et al. (2013) Large-scale collection and analysis of full-length cDNAs from Brachypodium distachyon and integration with Pooideae sequence resources. PLoS One 10: 75265.

- Ling HQ, Zhao S, Liu D, Wang J, Sun H, et al. (2013) Draft genome of the wheat A-genome progenitor Triticum urartu. Nature 496: 87-90.

- Jia J, Zhao S, Kong X, Li Y, Zhao G, et al. (2013) Aegilops tauschii draft genome sequence reveals a gene repertoire for wheat adaptation. Nature 496: 91-95.

- Krasileva KV, Buffalo V, Bailey P, Pearce S, Ayling S, et al. (2013) Separating homeologs by phasing in the tetraploid wheat transcriptome. Genome Biol 14: 66.

- Madlung A (2013) Polyploidy and its effect on evolutionary success: old questions revisited with new tools. Heredity 110: 99-104.

- Mayer KF, Taudien S, Martis M, Simková H, Suchánková P, et al. (2009) Gene content and virtual gene order of barley chromosome 1H. Plant Physiol 151: 496-505.

- Mochida K, Yoshida T, Sakurai T, Ogihara Y, Shinozaki K (2009) TriFLDB: A database of clustered full-length coding sequences from Triticeae with applications to comparative grass genomics. Plant Physiol 150: 1135-1146.

- Kihara H (1930) Genomanalyse bei Triticum und Aegilops. Cytologia 1: 263-284.

- Li A, Liu D, Wu J, Zhao X, Hao M, et al. (2014) mRNA and small RNA transcriptomes reveal insights into dynamic homoeolog regulation of allopolyploid heterosis in nascent hexaploid wheat. Plant Cell 26: 1878-1900.

- Chaundhary B, Flagel L, Stpar RM, Udall JA, Verma N, et al. (2009) Reciprocal silencing, transcriptional bias and functional divergence of homeologs in polyploid cotton (Gossypium). Genetics 182: 503-517.

- Rapp RA, Udall JA, Wendel JF (2009) Genomic expression dominance in allopolyploids. BMC Biol 7: 18.

- Pumphrey M, Bai J, Laudencia-Chingcuanco D, Anderson O, Gill BS (2009) Nonadditive expression of homoeologous genes is established upon polyploidization in hexaploid wheat. Genetics 181: 1147-1157.

- Chelaifa H, Chagué V, Chalabi S, Mestiri I, Arnaud D, et al. (2013) Prevalence of gene expression additivity in genetically stable wheat allohexaploids. New Phytol 197: 730-736.

- Madlung A, Wendel JF (2013) Genetic and epigenetic aspects of polyploid evolution in plants. Cytogenet Genome Res 140: 270-285.

- Feldman M, Liu B, Segal G, Abbo S, Levy AA, et al. (1997) Rapid elimination of low-copy DNA sequences in polyploid wheat: A possible mechanism for differentiation of homoeologous chromosomes. Genetics 147: 1381-1387.

- Li W, Huang L, Gill BS (2008) Recurrent deletions of puroindoline genes at the grain Hardness locus in four independent lineages of polyploid wheat. Plant Physiol 146: 200-212.

- Shaked H, Kashkush K, Ozkan H, Feldman M, Levy AA (2001) Sequence elimination and cytosine methylation are rapid and reproducible responses of the genome to wide hybridization and allopolyploidy in wheat. Plant Cell 13: 1749-1759.

- Chen ZJ (2010) Molecular mechanisms of polyploidy and hybrid vigor. Trends Plant Sci : 15: 57-71.

- Zhao N, Zhu B, Li M, Wang L, Xu L, et al. (2011) Extensive and heritable epigenetic remodeling and genetic stability accompany allohexaploidization of wheat. Genetics 188: 499-510.

- Shen H, He H, Li J, Chen W, Wang X, et al. (2012) Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression changes in two Arabidopsis ecotypes and their reciprocal hybrids. Plant Cell 24: 875-892.

- Shitsukawa N, Tahira C, Kassai K, Hirabayashi C, Shimizu T, et al. (2007) Genetic and epigenetic alteration among three homoeologous genes of a class E MADS box gene in hexaploid wheat. Plant Cell 19: 1723-1737.

- Hu Z, Han Z, Song N, Chai L, Yao Y, et al. (2013) Epigenetic modification contributes to the expression divergence of three TaEXPA1 homoeologs in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum). New Phytol 197: 1344-1352.

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, et al. (2011) Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-seq data. Nat Biotechnol 29: 644-652.

- Manickavelu A, Kawaura K, Oishi K, Shin-I T, Kohara Y, et al. (2012) Comprehensive functional analyses of expressed sequence tags in common wheat (Triticum aestivum). DNA Res 19: 165-177.

- Carver T, Bleasby A (2003) The design of Jemboss: a graphical user interface to EMBOSS. Bioinformatics 19: 1837-1843.

- Mitchell A, Chang HY, Daugherty L, Fraser M, Hunter S, et al. (2015) The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 213-221.

- McCarthy FM, Wang N, Magee GB, Nanduri B, Lawrence ML, et al. (2006) AgBase: a functional genomics resource for agriculture. BMC Genomics 7: 229.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES

(B) The number of located homoeogenes correlated positively with the DNA content of chromosomes except for 2DL and 5BL.

Citation: Mishina K, Kawaura K, Kamiya Y, Kajita Y, Mochida K, et al. (2018) Transcriptome of Homoeologous Genes Deduced from the Full-Length cDNA Clones of Common Wheat, Triticum aestivum L. J Genet Genomic Sci 3: 001.

Copyright: © 2018 Yasunari Ogihara, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.