Transhepatic Hemodialysis Catheter in a Patient with Access Failure: Case Report

*Corresponding Author(s):

Michelly Sampaio Bonates DuransDepartment Of Vascular And Endovascular Surgery, Presidente Dutra Hospital, Sao Luis, Brazil

Tel:+55 98984415841,

Email:michellybonates@gmail.com

Abstract

Although current guidelines advise against the use of Central Venous Catheters (CVC), the construction of Arterio-Venous (AV) fistulas and grafts is not always possible and many patients must chronically remain with tunnelled CVC. These patients who undergo catheter dependent Hemodialysis (HD) may exhaust traditional sites of catheter placement, which becomes a major problem. Steady exhaustion of central venous access options is an inevitable, potentially life-threatening outcome in patients who are dependent on long-term central venous catheters. Therefore, it is necessary to find another catheter access site with enough blood flow for dialysis. Transhepatic venous access for dialysis was described by Po et al., in a case report in 1994, is an acceptable but challenging vascular access technique. The aim of this study is to report the case of a successful hemodialysis transhepatic catheter implant in a patient with vascular access failure.

Keywords

Catheters; Hemodialysis; Transhepatic

INTRODUCTION

Although current guidelines advise against the use of Central Venous Catheters (CVC), the construction of Arterio-Venous (AV) fistulas and grafts is not always possible and many patients must chronically remain with tunnelled CVC. These patients who undergo catheter dependent Hemodialysis (HD) may exhaust traditional sites of catheter placement, which becomes a major problem [1,2].

Alternative access sites havebeen reported, including the femoral veins, collateral neck veins, translumbar Inferior Vena Cava (IVC), and renal veins. Transhepatic venous access for dialysis was described by Po et al., in a case report in 1994. Although considered a viable approach, the transhepatic dialysis catheter is believed to carry substantial risks [2]. Early complications include high rates or dislodgement and migration (37%), catheter-related sepsis (21.7%), and catheter thrombosis (17.4%). A case of acute Budd-Chiari syndrome in a pediatric patient has been reported [3].

When faced with a patient with exhausted access who needs placement of an unconventional dialysis catheter, a thorough history and physical examination is necessary. A detailed history of patient’s venous anatomy and prior access sites is crucial to understand potential options. Before performing unconventional (and therefore more risky) techniques, all efforts should be made to ensure any prior access sites cannot be salvaged [3].

Some researchers argue that the transhepatic route is superior to the translumbar route because of certain features: it can be used even in cases with occluded inferior venous cava; hemorrhage and migration are less frequent; there is a chance of transhepatic or endovascular embolization in case of hemorrhage; and vascular access in obese patients is easier. Furthermore, translumbar catheter revisions are more difficult because of a risk of retroperitoneal fibrosis [4].

The aim of this study was to report the case of a successful hemodialysis transhepatic catheter implant in a patient with vascular access failure.

CASE REPORT

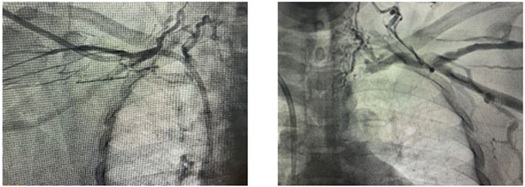

A 56-year-old female patient, black, hypertensive for 24 years, dialytic chronic kidney due to hypertensive nephropathy for 10 years, awaiting kidney transplantation. She was hospitalized for asthenia and difficulty walking. On admission, she presented hyperkalemia and severe metabolic acidosis (dialytic urgency), with non-functioning right femoral vein permcath. Prior history of multiple accesses for hemodialysis, including 6 arteriovenous fistulas, short and long-term catheters at various sites and peritoneal dialysis catheter implantation and removal due to infection. Other previous approaches included appendectomy 20 years ago, exploratory laparotomy and left lower extremity fasciotomy due to extensive psoas and thigh abscess, with primary focus on left femoral vein permcath. Phlebography performed subclavian and innominate vein occlusion on the right and left innominate vein occlusion with non-contrasted superior vena cava (Figure 1). They also showed inferior vena cava occlusion in the middle third and right iliac (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Phlebography performed subclavian and innominate vein occlusion on the right and left innominate vein occlusion with non-contrasted superior vena cava.

Figure 1: Phlebography performed subclavian and innominate vein occlusion on the right and left innominate vein occlusion with non-contrasted superior vena cava.

Figure 2: Inferior vena cava occlusion.

Figure 2: Inferior vena cava occlusion.

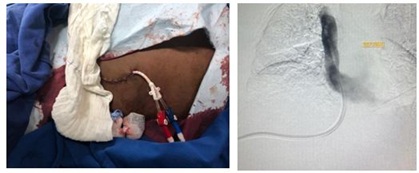

Central venous angioplasty was attempted for permcath implantation, but the catheter had low postoperative flow, making adequate dialysis impossible. A new catheter implantation for peritoneal dialysis was also attempted, but unsuccessfully due to the large amount of intra-abdominal adhesions. Short-stay catheter was implanted in the left femoral vein, but the catheter presented low flow. We then opted for transhepatic catheter implantation.Single dose of broad spectrum intra-venous antibiotic (Cefazolin 2g) was administrated 1h before the procedure. Patients lie in supine position, and the right side of the skin of abdomen and lower chest was sterilized. Under general anesthesia, transhepatic percutaneous puncture of the right hepatic vein tributary was performed by the Seldinger technique. We used intercostal approached with Chiba needle 18g and then 5F introducer under fluoroscopy. This was followed by injection of contrast medium showing drainage to the inferior vena cava at the atrio-caval junction and patency of the superior vena cava (Figure 3). Amplatz guide wire was introduced in hepatic vein, and secured up-wards in Superior Vena Cava (SVC) and right atrium, followed by dilatation of the right hepatic lobe parenchyma (Figure 4). Subcutaneous tunnel was formed anteroinferiorly and then the cateter (permcath 14Fx40cm) was inserted over the wire through the peel away sheath with distal end positioned in right atrium (Figure 5). Catheter showing good flow and reflux.

Figure 3: Drainage to the inferior vena cava at the atrio-caval junction.

Figure 3: Drainage to the inferior vena cava at the atrio-caval junction.

Figure 4: Amplatz guidewire passage to the right atrium and dilatation of the right hepatic lobe parenchyma.

Figure 4: Amplatz guidewire passage to the right atrium and dilatation of the right hepatic lobe parenchyma.

Figure 5: Transhepatic permcath with distal end positioned in right atrium.

Figure 5: Transhepatic permcath with distal end positioned in right atrium.

Patient had a good postoperative course with no complications. Follow-up of catheter for its patency and function was done via documentation by the nephrologists at dialysis center and communication with the interventional radiology specialist. Follow-up was performed by monitoring the catheter dialysis rate in each session. Also, inspection of catheter exit was done to exclude infection. Up to now, about 3 months later, it presents with satisfactory catheter dialysis.

DISCUSSION

There are three major types of vascular access: Arteriovenous Fistula (AVF), Arteriovenous Graft (AVG) and Tunneled Dialysis Catheters (TDCs). AVFs are the preferred vascular access type for dialysis, as they have the highest long-term patency rates and the lowest morbidity and mortality rates, but need at least 2 months to mature for optimal dialysis. The TDC serves as a bridge to AVF dialysis. Unfortunately, long-term use of TDCs often leads to infections, acute occlusions and chronic venous stenosis, depletion of the patient's conventional access routes and prevention of their recanalization. In such situations, the progressive loss of venous access sites prompts a systematic approach to alternative sites to maximize patient survival and minimize complications. Although several different veins can be chosen for the placement of a TDC, a vein can only be used for a limited amount of time before occlusions develop. Central venous stenosis remains common in dialysis patients. Steady exhaustion of central venous access options is an inevitable, potentially life-threatening outcome in patients who are dependent on long-term central venous catheters. Therefore, it is necessary to find another catheter access site with enough blood flow for dialysis [5].

Transhepatic catheter access is an acceptable but challenging vascular access technique that is often necessary in patients who have exhausted other endovascular options for central venous access. In patients with chronic total occlusion of internal jugular, subclavian, innominate and femoral veins with coexistent occlusion of the infrahepatic inferior vena cava, transhepatic catheter placement is the last acceptable option for central venous access [6].

It was first described by Po et al., in 1994 in one case [2,7] then was further scrutinized inthree retrospective studies comprising 12, 16, 22 and 38 adult patients in the following years. So there is only limited experience in using this method with small number of patients involved in different studies [7].

One of the largest study’s available, performed by Khallaf et al., analyses 296 patients for 750 days and obtained technical success in 100% [7], the same technical success was reported by Joaquim et al., [8]. In otter study, El Garib et al., [9] had a smaller population (23 patients) and short follow up period (365 days) and technical success of 88%. Mean cumulative duration of catheterin situ in the larger study was 577 days while in El Garib et al., study, maximum duration of catheter in situ was 300 days. In the Khallaf et al., study, the most common hepatic vein accesswas the right hepatic vein, the same that we used in our case. We also prefer the right hepatic vein as a first choice as it is peripheral (near thepuncture site) as well as it obtains a horizontal upperpart towards the inferior venous cava. Joaquim et al., [8] and El Garib et al., [9] also uses the righthepatic vein in all cases. In our case the tip of the hemodialysis catheter was in the right atrium. Coinciding with the most cases of Khallaf et al., [7] and El Garib et al., [9]. Joaquim et al., [8] put the catheter tip at the junction between SVC and right atrium in all six cases he performed. In our case the catheter is still in good function after 90 days, so we can’t tell yet how long it will last. The mean of functioning catheter was 280 days in Khallaf et al., [7] study. In 2003, Stavropoulos et al., studied 36 transhepatic catheters and reported a primary patency of just 24.3 days, the major reason being a high rate of late thrombosis [10]. Younes et al., in a study of 127 transhepatic catheters, reported a higher patency of 87.7 days [11]. Joaquim et al., [8] obtain a mean of 300.5 days functioning catheter in his small-sized study (only six patients). We also don’t have any complications yet. Exit site infection is the most common complication encountered in both studies Khallaf et al., [7] and El Garib et al., [9]. Sanal et al., [4]. Who aimed to investigate the safety and functionality of tunneled transhepatic hemodialysis catheters in chronic hemodialysis patients demonstrated that transhepatic venous route is safe and functional when used together with imaging modalities and by experienced hands. Some researchers argue that the transhepatic route is superior to the translumbar route because of certain features: it can be used even in cases with occluded IVC; hemorrhage and migration are less frequent; there is a chance of transhepatic or endovascular embolization in case of hemorrhage; and vascular access in obese patients is easier. Furthermore, translumbar catheter revisions are more difficult because of a risk of retroperitoneal fibrosis [4,9]. Data about the long-term effectiveness and safety of the procedure are still limited. In our hospital we count with interventional radiologistsand the procedure is technically relatively simple for them and can be successfully applied because of their experiences in biliary drainage and tunneled catheter placement through different peripheral veins. The experience of the surgeon must be considered in choosing the technique.

CONCLUSION

Steady exhaustion of central venous access options is an inevitable, potentially life-threatening outcome in patients who are dependent on long-term central venous catheters. Therefore, it is necessary to find another catheter access site with enough blood flow for dialysis. This case corroborated the literature in showing the safety and effectiveness of the transhepatic catheter for hemodialysis in a patient with vascular access failure. We still need more data about the long-term effectiveness and safety of the procedure.

REFERENCES

- Barros F, Carvalho B, Vaz R, Martins P, Neto R, et al. (2014) Acessos vasculares alternativos para hemodiálise - a experiência de um centro em cateteres trans-hepáticos e intracardíacos. Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension 28: 49-54.

- Smith TP, Ryan JM, Reddan DN (2004) Transhepatic catheter access for hemodialysis. Radiology 232: 246-251.

- Rahman S, Kuban JD (2017) Dialysis catheter placement in patients with exhausted access. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 20: 65-74.

- ?anal B, Nas ÖF, Do?an N, Korkmaz M, Hac?kurt K, et al. (2016) Safety and functionality of transhepatic hemodialysis catheters in chronic hemodialysis patients. Diagn Interv Radiol 22: 560-565.

- Pereira K, Osiason A, Salsamendi J (2015) Vascular access for placement of tunneled dialysis catheters for hemodialysis: a systematic approach and clinical practice algorithm. J Clin Imaging Sci 5: 31.

- Yevzlin AS, Asif A, Redfield RR, Beathard GA (2017) Dialysis Access Cases. In: Yevzlin AS, Asif A, Redfield III RR, Beathard G (eds). Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland.

- Khallaf OAN, El Tawab KAA, Korashi HI, Ibrahim GS, Mohamed RS (2019) Percutaneous transhepatic hemodialysis catheters in chronic hemodialysis patients: technique, functional outcome, and complications from a large population study. Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 50:

- Motta-Leal-Filho JMD, Carnevale FC, Nasser F, de Oliveira Sousa Junior W, Zurstrassen CE, et al. (2010) Percutaneous transhepatic venous access for hemodialysis: an alternative route for patients with end-stage renal failure. J Vasc Bras 9: 131-136.

- El Gharib M, Niazi G, Hetta W, Makkeyah Y (2014) Transhepatic venous catheters for hemodialysis. The Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 45: 431-438.

- Stavropoulos SW, Pan JJ, Clark TW, Soulen MC, Shlansky-Goldberg RD, et al. (2003) Percutaneous transhepatic venous access for hemodialysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 14: 1187-1190.

- Younes HK, Pettigrew CD, Anaya-Ayala JE, Soltes G, Saad WE, et al. (2011) Transhepatic hemodialysis catheters: functional outcome and comparison between early and late failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol 22: 183-191.

Citation: Durans MSB, Martins BB, de Araújo Junior RT, da Silva Frias Neto CA, de Brito Filho SB, et al. (2020) Transhepatic Hemodialysis Catheter in a Patient with Access Failure: Case Report. J Angiol Vasc Surg 5: 035.

Copyright: © 2020 Michelly Sampaio Bonates Durans, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.