Utilization and Clinical Outcome Following 5-Aminosalicylate Therapy for Crohn's Disease in Children

*Corresponding Author(s):

Bella ZeislerConnecticut Childrens Medical Center, Hartford, United States

Tel:+1 8605459560,

Fax:+1 860545956

Email:bzeisler@connecticutchildrens.org

Abstract

Study design: Data were obtained from a large observational inception cohort from 2002-2014. First, we analyzed initial treatments received immediately following diagnosis. Then, clinical outcome and disease activity were measured using the "Physician Global Assessment" (PGA) scale. The primary outcome was a PGA of "inactive", without corticosteroids (CS), immunomodulators, biologics or surgery one year following diagnosis in patients receiving 5-ASA ± CS only as initial therapy following diagnosis.

Results: 440/1297 subjects with CD (34%) received 5-ASA ± CS only as initial therapy, and were the focus of this study. No baseline differences were observed between the 5-ASA + CS (n=263) vs. 5-ASA - CS (n=177) treatment groups for age, gender, disease distribution or disease behavior. Baseline moderate/severe PGA was more common in the 5-ASA + CS group compared with the 5-ASA alone group (70% vs. 38%, p<0.001). The primary outcome was achieved by 34% of those treated with 5-ASA alone vs. 18% of those treated with 5-ASA + CS (p<0.001). In multivariate models, achieving the primary outcome was significantly associated with initially mild disease severity and no initial CS use.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

While efficacy supporting 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) use for the induction and maintenance of remission for Ulcerative Colitis (UC) has been well established in adult as well as several pediatric studies [1-6], evidence regarding 5-ASA use in Crohn's Disease (CD) for induction or maintenance of remission, or to prevent relapse after surgically induced remission, is conflicting and weak [7-12]. Despite the absence of strong supporting data, 5-ASA compounds are commonly prescribed for CD in general clinical practice. A 2014 Swiss Cohort study including adults and children found that among 1420 patients with CD 59% of patients had been treated with 5-ASA at some time [13].

From our large prospective, inception cohort of children newly diagnosed with CD which included patients from 30 pediatric centers in North America managed by independently practicing pediatric gastroenterologists we aimed to:

(1) Describe the prevalence of 5-ASA utilization

(2) Describe clinical outcomes at 1-3 years following therapy with 5-ASA ± corticosteroids (CS)

(3) Identify clinical and demographic factors associated with clinical remission

METHODS AND STUDY POPULATION

Per our first aim, we collected data on initial treatment prescribed following diagnosis. For this we analyzed treatments listed at 30 days following diagnosis which was the first data collection point following diagnosis. We looked at the utilization of 5-ASA alone as well as in combination with other treatments. We also collected information on the utilization of other treatments regimens that did not include 5-ASA.

Next, we focused on the group of patients who received 5-ASA as the only maintenance therapy given initially following diagnosis in order to study outcomes among these patients. For this analysis we included patients also given corticosteroids (CS) initially for induction of remission. In addition, we did not exclude the small number of patients who also received rectal therapies. However, we excluded all patients receiving any other CD-specific oral or parenteral maintenance treatment at 30 days following diagnosis. Approximately 97% of patients receiving 5-ASA received mesalamine and only 3% received sulfasalazine. In order to simplify our statistical analysis, we combined results and refer to both compounds collectively as 5-ASA. Dose was recorded when available and expressed in mg/kg/day.

Disease activity and outcome measures for 5-ASA use

The primary clinical outcome for our analysis was remission at 1 year or "inactive disease" by PGA designation, off CS, and without escalation of therapy to immunomodulators (IM), anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) therapy, or resectional surgery. A secondary outcome measure was "response" or "mild disease" by PGA designation with similar constraints. Additional secondary outcomes included disease activity by PGA at two years and three years following diagnosis, as well as by Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) when data for calculation were available [16].

Statistical analysis

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

RESULTS

Deriving the study population and utilization of 5-ASA

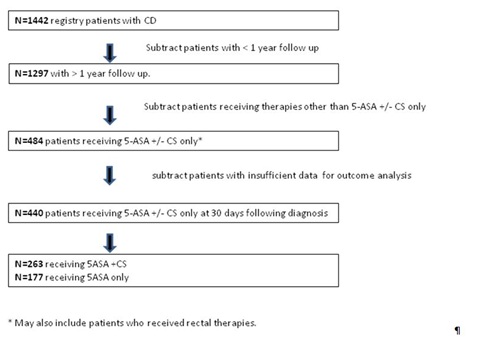

Figure 1: Study patient derivation and initial treatments received at 30 days following diagnosis.

Figure 1: Study patient derivation and initial treatments received at 30 days following diagnosis.| N= 1297* | % | |

| 5-ASA | 682 | 53% |

| IM | 517 | 40% |

| Anti-TNF | 90 | 7% |

| Enteral | 67 | 5% |

| Rectal therapies | 45 | 3% |

| Surgery | 10 | < 1% |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | 2 | < 1% |

Table 1A: Use frequency alone or in combination at 30 days following diagnosis.

| N= 1297 | % | |

| 5-ASA + CS | 280 | 22% |

| CS + IM | 252 | 19% |

| 5-ASA alone | 204 | 16% |

| 5-ASA + CS + IM | 148 | 11% |

| CS alone | 147 | 11% |

| Enteral therapy aloneSurgery | 38 | 3% |

| IM alone | 28 | 2% |

| CS + anti-TNF | 26 | 2% |

| CS + IM + anti-TNF | 20 | 2% |

| Total ** | 88% (n=1143) |

Table 1B: Most frequent treatment combinations at 30 days***.

*Total > 1297 due to patients receiving multiple treatments

***combinations also included patients receiving rectal therapies

**The above 9 most frequent treatment combinations represent the regimens for 88% (1143) of the 1297 patients. There were 22 additional combinations which account for the remaining 12% of patients (154).

In order to analyze 1 year outcomes data following 5-ASA use, we identified the subset of individuals for whom 5-ASA ± CS was prescribed as the only therapy by 30 days followed diagnosis (n=484). Forty-four of these patients were excluded from further analysis because of incomplete data, leaving 440 subjects (34% of all patients with CD in this study with >1 year of follow up) who form our study group. Of these patients, 177 received 5-ASA without CS and 263 received 5-ASA with CS at 30 days following diagnosis Figure 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at diagnosis of study population

| Characteristic |

CD patients who received 5-ASA only in first 30 days from diagnosis (N=177) |

CD patients who received 5-ASA + CS only in first 30 days from diagnosis (N=263) |

| Gender (Male) | 92 (52%) | 147 (56%) |

| Age (years) | 11.4 ± 3.2 | 11.9 ± 2.9 |

|

Disease distribution |

25 (14%) |

30 (11%) |

|

PGA *** |

110 (62%) |

78 (30%) |

| PCDAI *** (# available) | 23 ± 13 (101) | 30 ± 15 (129) |

| Perianal disease present | 18 (11%) | 13 (5%) |

|

Behavior (Paris classification) |

166 (96%) |

235 (95%) |

| Hemoglobin | 11.6 ± 1.6 | 11.5 ± 2.0 |

| ESR *** | 27 ± 16 | 34 ± 20 |

| Albumin *** | 3.62 ± 0.57 | 3.32 ± 0.65 |

| Platelet count * | 438 ± 150 | 474 ± 154 |

|

Growth failure Height Z-score <-1.65 Height Z-score ≥-1.65 |

23 (13%) 154 (87%) |

26 (10%) 231 (90%) |

|

5-ASA dose |

54 ± 20 |

51 ± 20 |

Table 2: Distribution of characteristics at diagnosis for all Crohn's Disease patients with at least one year of follow-up and for the subsets of study patients who received 5-ASA ± corticosteroids in the first 30 days from diagnosis.

CD-Crohn's Disease; CS-Corticosteroids; PGA-Physician's Global Assessment of disease severity;

PCDAI-Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index; ESR-Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate.

Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation or frequency (percent).

* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 comparing patients receiving 5-ASA alone vs. 5ASA + CS.

Clinical outcomes at 1 year

| 1 year outcomes | N | Remission at 1 year | Response only at 1 year | Response only at 1 year |

| All Patients combined | 440 | 108 (25%) | 37 (8%) | 295 (67%) |

| By therapy at 30 days following diagnosis*** | ||||

| 5-ASA Only | 177 | 60 (34%) | 28 (16%) | 89 (50%) |

| 5-ASA + CS | 263 | 48 (18%) | 9 (3%) | 206 (78%) |

| By PGA at 30 days following diagnosis*** | ||||

| Mild | 188 | 62 (33%) | 26 (14%) | 100 (53%) |

| Moderate/Severe | 252 | 46 (18%) | 11 (4%) | 195 (77%) |

| By therapy and PGA at 30 days following diagnosis*** | ||||

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Mild | 110 | 43 (39%) | 21 (19%) | 46 (42%) |

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Moderate/Severe | 67 | 17 (25%) | 7 (10%) | 43 (64%) |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Mild | 78 | 19 (24%) | 5 (6%) | 54 (69%) |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Moderate/Severe | 185 | 29 (16%) | 4 (2%) | 152 (82%) |

Clinical outcomes at 2 - 3 years

|

2 year outcomes |

N | Remission at 2 years | Response only at 2 years | Not in remission or response at 2 years |

| All Patients combined | 365 | 64 (18%) | 16 (4%) | 285 (78%) |

| By therapy at 30 days following diagnosis*** | ||||

| 5-ASA Only | 148 | 40 (27%) | 13 (9%) | 95 (64%) |

| 5-ASA + CS | 217 | 24 (11%) | 3 (1%) | 190 (88%) |

| By PGA at 30 days following diagnosis * | ||||

| Mild | 153 | 36 (24%) | 14 (9%) | 103 (67%) |

| Moderate/Severe | 212 | 28 (13%) | 2 (1%) | 182 (86%) |

| By therapy and PGA at 30 days following diagnosis *** | ||||

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Mild | 90 | 29 (32%) | 12 (13%) | 49 (54%) |

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Moderate/Severe | 58 | 11 (19%) | 1 (2%) | 46 (79%) |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Mild | 63 | 7 (11%) | 2 (3%) | 54 (86%) |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Moderate/Severe | 154 | 17 (11%) | 1 (1%) | 136 (88%) |

|

3 year outcomes |

N | Remission at 3 years | Response only at 3 years | Not in remission or response at 3 years |

| All Patients combined | 289 | 38 (13%) | 8 (3%) | 243 (84%) |

| By therapy at 30 days following diagnosis*** | ||||

| 5-ASA Only | 107 | 25 (23%) | 5 (5%) | 77 (72%) |

| 5-ASA + CS | 182 | 13 (7%) | 3 (2%) | 166 (91%) |

| By PGA at 30 days following diagnosis * | ||||

| Mild | 115 | 21 (18%) | 6 (5%) | 88 (77%) |

| Moderate/Severe | 174 | 17 (10%) | 2 (1%) | 155 (89%) |

| By therapy and PGA at 30 days following diagnosis *** | ||||

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Mild | 62 | 17 (27%) | 4 (7%) | 41 (66%) |

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Moderate/Severe | 45 | 8 (18%) | 1 (2%) | 36 (80%) |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Mild | 53 | 4 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 47 (89%) |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Moderate/Severe | 129 | 9 (7%) | 1 (1%) | 119 (92%) |

| 1 year | 2 year | 3 year | |

| By therapy group *** | |||

| 5-ASA Only | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

| 5-ASA + CS | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 |

| By PGA *** | |||

| Mild | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.03 |

| Moderate/Severe | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| By therapy group and PGA *** | |||

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Mild | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.05 |

| 5-ASA Only and PGA Moderate/Severe | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.05 |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Mild | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.04 |

| 5-ASA + CS and PGA Moderate/Severe | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 |

PCDAI

Laboratory studies

Growth

Predictors of response

| Characteristic | Reference Group | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | Adjusted OR (95% CI)2 | Adjusted OR (95% CI)3 |

| Therapy in first 30 days (5-ASA ± CS) | 5-ASA + CS | 2.30 (1.48-3.57)*** | 2.19 (1.32-3.63)** | 2.21 (1.36-3.59)*** | 1.91 (1.20-3.05)** |

| Gender | Male | 0.85 (0.55-1.31) | |||

| Age (<10 vs. 10+) | <10 | 0.79 (0.44-1.05) | |||

| Age (<12 vs. 12+) | <12 | 0.68 (0.48-1.06) | |||

| Disease extent (small/large bowel only vs. both) | Both small & large | 1.24 (0.80-1.93) | |||

| Physician Global Assessment (PGA) | Moderate/severe | 2.20 (1.42-3.43)*** | 2.13 (1.29-3.53)** | 1.78 (1.10-2.89)* | 1.81 (1.13-2.88)* |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | Abnormal (>20) | 1.70 (1.05-2.74)* | |||

|

Hemoglobin (HGB) Albumin (ALB) |

Abnormal (<11) Abnormal (<3.5) |

1.25 (0.77-2.00) 1.67 (1.04-2.67)* |

|||

| Any of above lab tests abnormal (ANYLAB) | Yes | 2.00 (1.18-3.40)* |

Table 4: Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of remission at one year4 following diagnosis of Crohn's Disease for study groups (N=440): results show Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for potential risk factors at diagnosis and therapy in first 30 days.

1. Forward selection model including therapy, PGA, ESR and ALB (N=365)

2. Forward selection model including therapy, PGA and ANYLAB (N=404)

3. Full model including therapy and PGA (N=440)

4. Remission at one year following diagnosis=PGA inactive, not receiving Corticosteroids (CS), and no rescue with immunomodulators, biologics or surgery during first year; N=108 in remission, N=332 not in remission

* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

For most children with CD who present with moderate to severe symptoms, and often with growth delay, current therapy frequently includes the early use of immunomodulators and biologics [19,20] which indeed, has been associated with improved clinical outcomes at one year following diagnosis of very ill children [21]. More difficult, however, is choosing initial therapy in those children who present with mild disease for whom there is parental and sometimes clinician reluctance to use therapies associated with potentially more significant side effects. 5-ASA therapy, which is perceived to have a more favorable side effect profile, is often used per anecdotal evidence as well as sparse published data [13] for patients with milder disease despite minimal data in the pediatric (or adult) Crohn's disease literature to support this practice.

In this prospective multicenter observational registry study, we aimed to provide data on 5-ASA utilization among children newly diagnosed with CD. We also aimed to describe clinical outcomes in patients following 5-ASA treatment. At 30 days following a CD diagnosis which is the first data collection point in our study design, 5-ASA appears to be the most frequent initial treatment prescribed with over half (53%) of all patients receiving 5-ASA either alone or in combination. Furthermore, over one-third (37%) of patients received only 5-ASA ± CS in the first 30 days following diagnosis. Outcomes data show that 25% of all study subjects who started on only 5-ASA +/- CS had clinically inactive disease without the need for CS or step up therapy at 1 year following diagnosis. When stratified by PGA at diagnosis and/or need for CS at 30 days, 1 year outcomes varied considerably. CS-free remission or response at 1 year without step up therapy was as high as 58% for the subgroup of patients with mild PGA at diagnosis whom were not given CS initially. Among patients with moderate/severe PGA at diagnosis who were given initial CS (undoubtedly reflecting a sicker population), only 18% achieved primary or secondary outcome. We did not find that disease location, age, or gender influenced outcomes.

When looking at outcomes data after 2-3 years, favorable outcomes diminished considerably. Patients started on only 5-ASA +/- CS at diagnosis whom had clinically inactive disease without the need for CS or step up therapy at 2 and 3 years, were 22% and 16%, respectively. The subset who were most likely to have a favorable outcome at 2 and 3 years were those receiving 5-ASA only without CS and who had mild PGA at diagnosis. For this subset, remission or response was noted to be 46% and 34% at 2 and 3 years, respectively.

As this was not a controlled study with a single preparation of 5-ASA we are only able to give dosing data in aggregate. The mean 5-ASA dose was about 50 mg/kg/day. Given that efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis may be improved with higher dosing schedules [22] as well as some adult CD studies that provide data on dose [12]. It is possible that dosing greater than 50 mg/kg/day might be more effective.

The main strengths of our study are the size of the population studied and the breadth of an experience from multiple institutions reflecting true real world experience. However, our study is not a randomized, case-control clinical trial. All treatment choices were dictated by physician discretion and were not protocol based including doses and specific formulations of 5-ASA compounds, use of rectal therapies, and decision to start or move to alternative therapies. Therefore, placebo effect and/or selection bias should be considered. While placebo effect has been demonstrated in adult clinical trials of inflammatory bowel disease [23,24], similar studies have not been conducted in pediatrics and therefore, we have no data on the potential size of this effect in our population. We did note, however, that standard laboratory measures of disease activity normalized in many patients who achieved an inactive PGA suggesting improvement of inflammation.

In addition, adherence was not systematically monitored and can be a significant confounder. And other markers that may potentially correlate with clinical outcomes that have gained more uniform use were not systematically collected throughout the study period and were not included in our analysis. Such markers include C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, X-ray computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance enterography and repeat endoscopic examinations to document mucosal healing. The use of PGA as an outcome variable is not ideal though reasonable correlation with PCDAI has been demonstrated [16]. Since PGA was all that was available for many of the study subjects, it was therefore utilized for our study analysis. We presented PCDAI data when available.

Given that over half of children newly diagnosed with CD are receiving 5-ASA medications as part of their initial therapy, it is important to develop evidence on efficacy or futility. It is highly unlikely that future placebo controlled trials of 5-ASA will be conducted in children and therefore observational registry data may be all that is available. pediatric literature and clinical experience, most pediatric practitioners would agree that use of 5-ASA monotherapy is not appropriate for pediatric patients with CD who demonstrate moderate to severe phenotypical features including extensive small bowel disease, stricturing or penetrating disease, or disease that impacts on growth or pubertal development [19-21]. Our data suggest the possibility of clinical utility in select patients with initially mild disease, though further exploration of specific compounds as well as dosing schedules would be helpful. For patients with more significant disease activity, however, our outcomes data (1-3 years following diagnosis) suggests that the use of 5-ASA as primary therapy does not appear to be efficacious. The development of newer risk stratification tools including serology, genetics and microbiome analysis may help identify patients at lower risk for progressive disease [25].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS/SOURCES OF FUNDING AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Early support for the present study came from an unrestricted grant provided by Janssen Ortho-Biotech. There was no external funding from 2012 to the close of the Registry.

We would like to acknowledge participants of the "Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborative Research Group Registry" for enrolling patients, collecting and submitting data to the centralized data management center.

Bella Zeisler, Trudy Lerer, report no conflicts of interest. Jeffrey Hyams reports the following disclosures: Janssen Ortho Biotech-research support, advisory board. Consultant Abbvie, Celgene, Takeda, Lilly, Boerhinger Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca. Shire- research support.

ROLES IN THE SUBMITTED WORK

Bella Zeisler - Design of work, interpretation of data, drafting and revising work, final approval and accountability.

Jeffrey Hyams - Acquisition of data, design of work, interpretation of data, drafting and revising work, final approval and accountability.

Trudy Lerer - Design of work, interpretation of data, statistical analysis drafting and revising work, final approval and accountability.

REFERENCES

- Sutherland L, Macdonald JK (2006) Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 543.

- Sutherland L, Macdonald JK (2006) Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Re 544.

- Ford AC, Achkar JP, Khan KJ, kane SV, Talley NJ, et al. (2011) Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 106: 601-616.

- Ferry GD, Kirschner BS, Grand RJ, Issenman RM, Griffiths AM, et al. (1993) Olsalazine versus sulfasalazine in mild to moderate childhood ulcerative colitis: results of the Pediatric Gastroenterology Collaborative Research Group Clinical Trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 17: 32-38.

- Hyams JS, Davis P, Grancher K, Lerer T, Justinich CJ, et al. (1996) Clinical outcome of ulcerative colitis in children. J Pediatr 129: 81-88.

- Zeisler B, Lerer T, Markowitz J, Mack D, Griffiths A, et al. (2013) Outcome following aminosalicylate therapy in children newly diagnosed as having ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 56: 12-18.

- Ford AC, Kane SV, Khan KJ, Achkar JP, Talley NJ, et al. (2011) Efficacy of 5-aminosalicylates in Crohn's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 106: 617-629.

- Ford AC, Khan KJ, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P (2011) 5-aminosalicylates prevent relapse of Crohn's disease after surgically induced remission: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 106: 413-420.

- Lim WC, Hanauer S (2010) Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8870.

- Gordon M, Naidoo K, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK (2011) Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of surgically-induced remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8414.

- Hanauer SB, Stromberg U (2004) Oral Pentasa in the treatment of active Crohn's disease: A meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2: 379-388.

- Lim WC, Wang Y, MacDonald JK, Hanauer S (2016)Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: 8870.

- Schoepfer AM, Bortolotti M, Pittet V, Mottet C, Gonvers JJ, et al. (2014) The gap between scientific evidence and clinical practice: 5-aminosalicylates are frequently used for the treatment of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 40: 930-937.

- Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, Turner D, et al. (2011) Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17: 1314-1321.

- Hyams J, Markowitz J, Otley A, Rosh J, Mack D, et al. (2005) Evaluation of the pediatric crohn disease activity index: a prospective multicenter experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 41: 416-421.

- Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, Gryboski JD, Kibort PM, et al. (1991) Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn's disease activity index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 12: 439-447.

- Motil KJ, Grand RJ, Davis-Kraft L, Ferlic LL, Smith EO (1993) Growth failure in children with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 105: 681-691.

- Wine E, Reif SS, Leshinsky-Silver E, Weiss B, Shaoul RR, et al. (2004) Pediatric Crohn's disease and growth retardation: the role of genotype, phenotype, and disease severity. Pediatrics 114: 1281-1286.

- Pfefferkorn M, Burke G, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Rosh J, et al. (2009) Growth abnormalities persist in newly diagnosed children with crohn disease despite current treatment paradigms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 48: 168-174.

- Grossi V, Lerer T, Griffiths A, LeLeiko N, Cabrera J, et al. (2015) Concomitant Use of Immunomodulators Affects the Durability of Infliximab Therapy in Children With Crohn's Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 1748-1756.

- Walters TD, Kim MO, Denson LA, Griffiths AM, Dubinsky M, et al. (2014)Increased effectiveness of early therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha vs an immunomodulator in children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 146: 383-391.

- Hanauer SB (2006) Review article: high-dose aminosalicylates to induce and maintain remissions in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 3: 37-40.

- Ilnyckyj A, Shanahan F, Anton PA, Cheang M, Bernstein CN (1997) Quantification of the placebo response in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 112: 1854-1858.

- Su C, Lichtenstein GR, Krok K, Brensinger CM, Lewis JD (2004) A meta-analysis of the placebo rates of remission and response in clinical trials of active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 126: 1257-1269.

- Dubinsky MC (2010) Serologic and laboratory markers in prediction of the disease course in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 16: 2604-2608.

Citation: Zeisler B, Lerer T, Hyams J (2018) Utilization and Clinical Outcome Following 5-Aminosalicylate Therapy for Crohn's Disease in Children. J Gastroenterol Hepatology Res 3: 016.

Copyright: © 2018 Bella Zeisler, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.