Validation of an Empathy Film with Health Care Students

*Corresponding Author(s):

Jessie JanssenJosef Ressel Centre, Horizons Of Personalized Music Therapy – Researching Music Therapy Processes And Relationships In Selected Fields Of Neurologic Rehabilitation, Department Of Health Sciences, Institute Of Therapeutic Sciences, IMC University Of Applied Sciences Krems, Krems An Der Donau, Austria

Tel:+43 2732802165,

Email:jessie.janssen@fh-krems.ac.at

Abstract

Empathy is important for healthcare professionals; however, measuring empathy is difficult. Films have been used to evoke relatively simple emotions such as anger and happiness; however limited evidence exists for emotional complex responses such as empathy. In this randomised cross-over study we explore if a Film Sequence (‘Removed’) (EFS) would evoke a more empathic response than a Control Film Sequence (CFS). Students of a local University of applied science were assigned to one of two experimental conditions (EFS versus CFS) on day one, and the conditions were reversed on day two. Outcome measures were the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) score, Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and the Saarbrucken Personality Questionnaire (SPQ). Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to detect significant differences in the PANAS and HRV, between CFS and EFS. Spearman correlation coefficients calculated the correlations between the outcome measures. Eighteen female participants, median age 23 years old (IQR 20-32), participated in the study. Participants’ emotions were significantly more positively affected by the CFS than the EFS (W=171, p<0.001), whereas the EFS evoked significantly more negative emotions than the CFS (W= 0, p< 0.001). A significant difference in negative effect of the PANAS and HRV were correlated with the SPQ (r=0.55; r=-0.52). This study showed that the EFS was able to evoke an emotional response in young women, which was correlated to empathy. Verification of these results is needed with a larger, more representative sample. The film could be used to evaluate the effectiveness of empathy training in health professions.

Keywords

Empathy; Health care; Control film sequence; Empathy film sequence

INTRODUCTION

Empathy is a complex emotional response which had been defined in different ways by different disciplines. In a recent review, empathy has been defined as ‘an emotional response (affective), dependent upon the interaction between trait capacities and state influences. Empathic processes are automatically elicited but are also shaped by top-down control processes. The resulting emotion is similar to one’s perception (directly experienced or imagined) and understanding (cognitive empathy) of the stimulus emotion, with recognition that the source of the emotion is not one’s own’ [1].

Empathy Allows sallied Health Professionals’ (AHPs) to react to the patient’s experiences and concerns, which is crucial for a positive relationship between patients and AHPs [2]. This positive empathic relationship can in turn improve patient outcomes [3]. Therefore, it is important that current AHP students are trained in empathy.

Within the context of psychological research, trigger films have been used to evoke an emotion. Initially relatively simple emotions have been investigated, such as fear, anger, sadness, disgust, amusement, tenderness, excitement, happiness, surprise [4,5] or gratitude, joy, determination, hope, awe, serenity, interest [6]. Later, but to a more limited extend, more complex emotional responses such as empathy were investigated. Forster and Hoekstra [7,8] explored four films (‘the last king of Scotland’, ‘American History X’, ‘Monster's Ball’ and ‘the road’) with potential empathic content, however specific sequences in order to measure the empathic response were not given. In 2014 Howard [9] used self-reported questionnaires to compare responses to empathy sequences (positive and negative), with non-empathy unpleasant sequences (horror). Empathic film sequences elicited higher levels of empathic concern, using the modified version of the Post Film Questionnaire [10], than the other sequences. These empathic film sequences were all from mainstream films, such as ‘Up’ and ‘the colour purple’, which has a high probability to have already been seen by participants.

Physiological responses have also been used to measure empathy. Jackson et al., [11] found differences in self perspective and other perspectives when looking at empathy in pain using functional MRI. A more clinically pragmatic approach was used by Krauth in 2010 [12], exploring the link between Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and empathic responses to categories of images: unempathic (positive and negative), empathic (positive and negative). The standard deviation of the time interval between successive ECG R-waves (SDNN) showed a significant difference between unempathic and empathic images.

Currently no literature exists about the use of trigger films in evoking empathic responses using a combination of questionnaires and HRV. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the empathic response on a relatively unknown short film sequence using questionnaires and heart rate variability.

METHODS

Design

This crossover study was part of an overarching project aimed to explore if empathy could be measured with a combination of questionnaires, HRV and biomarkers from saliva samples. The study presented in this paper represents the first part of this overarching project and focused on the validation of the film using the questionnaires and the HRV. In this cross-over study each participant was randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions: Empathy Film Sequence (EFS) versus Control Film Sequence (CFS). The study protocol was sent to the ethics committee in Lower Austria (NiederösterreichEthikkommission in St. Pölten), which confirmed no further ethics application was necessary.

Recruitment

Students of the music therapy course at the Institute of Therapeutic Sciences at IMC University of Applied Sciences, Krems were invited to take part in the study. An information sheet was sent out a week before the first scheduled data collection day. In addition, an informal presentation by the course leader took place in order to explain the goals, procedure and voluntary nature of the study. Students could then ask any remaining questions.

Students were included in the study if they were aged between 18 and 99 years, and provided written informed consent. When students were allergic or had other contraindication to adhesive electrodes they were excluded from the study.

Procedure

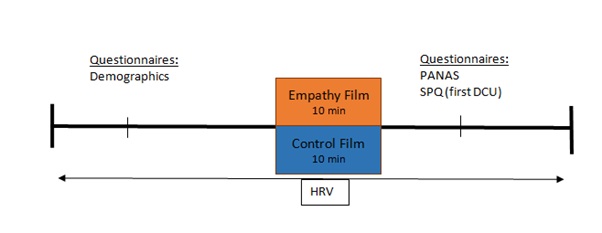

The data collection consisted of two data collection units. These took place on two days within a month. After the participants provided informed consent they were randomly divided into two groups, one group watched the EFS, the other the CFS. The participants were blinded for group allocation. Each group was led to a different room in order to allow the study to run in parallel. A graphical representation of the study is displayed in figure 1, a detailed description of the procedures in each group are listed below.

Figure 1: Procedure of data collection. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, SPQ = Saarbrucken Personality Questionnaire, DCU= Data Collection Unit, HRV= Heart Rate Variability.

First, the participants were fitted with a heart rate monitor (Emotion ACG sensor, Mega Electronics Ltd). All monitors started recording simultaneously and continued to do so throughout the entire duration of the study. Subsequently, a demographic questionnaire was asked to be filled out, which asked about age, gender, education, possible medication and chronic diseases.

The film sequence was then shown. The EFS was intended to evoke a strong emotional empathic response, with the freely available YouTube video “ReMoved- Torn Out”. As the CFS, a video produced especially for this study was shown, which was assumed not to evoke a positive or negative emotion. The duration of these film sequences was identical, 10:02 minutes. More information on both films can be found under the section Film.

In the last phase of the data collection unit the participants were asked to assess the emotions of the protagonist of the video sequences with regard to their quality and intensity using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [13]. In addition, the Saarbrucken Personality Questionnaire (SPQ) [14], which is the German translation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index [15,16], was completed.

The second data collection unit was carried out in the same manner as the first, with the main difference that each group was shown the other film sequence and the SPQ was not completed. Figure 1 below shows the time course of the first and second data collection units, which lasted about 45 minutes.

Measures

The main outcome measure was the PANAS and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). The PANAS consists of 20 questions about how participants feel after they saw the film, 10 questions are focused on positive emotions, with the remaining 10 are focused on negative emotions. The mean value for both the positive and negative aspects was calculated for analysis. For the aim of this project the participants were asking to rate the emotions of the protagonists in the film sequence.

The secondary outcome measure was the HRV. HRV was measured throughout the data collection period. Three five-minute timeslots were selected for analysis: pre-, during- and post-film. The pre- and post-film samples were taken when the participants started to complete the questionnaires, where as the during film sample was taken for five minutes during the film. Data was stored in Lebensfeuer® Analyse portal (Autonom Health®) and analysed in Kubios premium 3.2.0. Variables from the time, frequency and nonlinear domain were used [17] (Table 1).

|

HRV Domain |

Variable |

Description |

|

Time |

Mean HR |

Mean heartrate (1/min) |

|

SDNN |

Standard deviation of RR intervals (ms) |

|

|

RMSSD |

Square root of the mean squared differences between successive RR intervals (ms) |

|

|

pNN50 |

Number of successive RR interval pairs that differ more than 50 milliseconds (NN50) divided by the total number of RR intervals |

|

|

Frequency |

LF abs |

Absolute power of LF(ms2) in Fast Fourier transform (FFT) |

|

HF abs |

Absolute power of HF (ms2) in FFT |

|

|

LF(n.u.) |

Power of LF in normalised units (LF[ms2]/(total power (VLF+LF+HF) [ms2]−VLF[ms2]) |

|

|

HF(n.u.)

|

Power of HF band in normalised units (HF[ms2]/(total power (VLF+LF+HF) [ms2]−VLF[ms2]) |

|

|

LF/HF ratio |

Ratio between LF and HF band powers LF/HF |

|

|

nonlinear |

SD1 |

In Poincaré plot, the standard deviation perpendicular to the line-of-identity |

|

SD2 |

In Poincaré plot, the standard deviation along the line-of-identity |

|

|

SD2/SD1 |

Ratio between SD2 and SD1 |

Table 1: Overview of the HRV variables.

RR=Time interval between successive ECG R-waves, LF=low frequency= 0.04 Hz till 0.15 Hz, HF=high frequency=HF: 0.15 Hz till 0.4 Hz, VLF= very low frequency=0-0.04 Hz.

Film

The freely available YouTube video

“"ReMoved- Torn Out” was used as a trigger film for an empathic response (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOeQUwdAjE0). This film was made to create awareness, to encourage and to be useful in the training of foster parents. It is about a 10-year-old girl who navigates her way through the foster care system, after being removed from her home and separated from her younger brother. Since the quality of the transmitted emotion changes towards the end of the film, it was only shown until 10:02. Permission was obtained to use this film for this study (personal communication). In the CFS an actor told the audience about his holiday in the mountains. The CFS was especially made for this study.

Analysis

Demographics of the participants were listed in median and Inter Quartile Range (IQR), due to the small sample size. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to detect significant differences in positive and negative emotions, as measured by the PANAS, between CFS and EFS.

In order to identify changes induced by the films, the HRV variables were transformed into relative variables by dividing the values prior to the film sequence by the value during the film sequence. The values after the film sequence were divided by the values during the film sequence. The Wilcoxon signed rank test then calculated the significant differences between the CFS and the EFS. The spearman correlation was used to explore the correlation between the PANAS and HRV variables with SPQ.

RESULTS

Twenty-one participants were randomized to commence either with the EFS or the CFS. Complete data sets failed in three participants and thus were excluded from the analysis. All 18 participants were female and had a median age of 23 years (IQR 20-32, range 19-41). Thirteen participants had finished secondary school, three university of applied science and two received other education. Ten participants started with the EFS on the first day (study group EFS-CFS), and eight participants started with the CFS (study group CFS-EFS). Participants scored a median of 49 (IQR 46-51) on the SPQ.

Positive (PA) and Negative Affect (NA) between the control and empathy film sequence

Both the PA and NA were significantly different between the two films sequences (Table 2). Participants reported to be significantly more positively affected by the CFS than the EFS (W=171, p<0.001), whereas the EFS evoked significantly more negative emotions than the CFS (W= 0, p< 0.001).

|

PANAS score |

Empathy film sequence |

Control film sequence |

|

|

Median (IQR) |

Median (IQR) |

|

Positive affect** |

2.4 (2.2-2.7) |

4.2 (4.1-4.5) |

|

Negative affect** |

3.3 (2.9-3.4) |

1.3 (1.3-1.6) |

Table 2: Differences between empathy and control film sequences in PANAS sub scores positive affect and negative effect.

** p

HRV differences between control and empathy film sequence

The Wilcoxson signed ranked test showed significant differences in the absolute power of low frequency and the high frequency range of the heart rate variables between the EFS and the CFS (respectively W=39, SE=22.9, p=0,043; W=29, SE=22.9, p=0,014). This was only present when the value after the film was divided by the value during the film (Table 3).

|

HRV Domain |

Variable |

|

Empathy film sequence |

Control film sequence |

|

|

|

Median (IQR) |

Median (IQR) |

p-value |

||

|

Time |

Mean HR |

Δ12 |

0.94 (0.924-0.986) |

0.95 (0.918-0.964) |

0.711 |

|

Δ32 |

0.99 (0.941-1.017) |

0.99 (0.962-1.013) |

0.372 |

||

|

SDNN |

Δ12 |

1.01 (0.850-1.212) |

0.88 (0.797-1.094) |

0.112 |

|

|

Δ32 |

0.96 (0.838-1.088) |

0.87 (0.737-1.005) |

0.78 |

||

|

RMSSD |

Δ12 |

1.14 (1.007-1.340) |

1.07 (0.954-1.272) |

0.372 |

|

|

Δ32 |

1.11 (0.904-1.216) |

0.97 (0.753-1.091) |

0.199 |

||

|

pNN50 |

Δ12 |

1.24 (0.878-1.968) |

1.39 (0.974-1.757) |

0.981 |

|

|

Δ32 |

1.17 (0.810-1.817) |

1.00 (0.763-1.313) |

0.157 |

||

|

Frequency |

LFabs |

Δ12 |

0.82 (0.570-1.205) |

0.76 (0.410-1.015) |

0.586 |

|

Δ32 |

0.97 (0.417-1.306) |

0.59 (0.448-0.853) |

0.043 |

||

|

HFabs |

Δ12 |

1.53 (0.984-2.286) |

1.20 (0.703-1.735) |

0.078 |

|

|

Δ32 |

1.43 (0.718-1.836) |

0.83 (0.479-1.191) |

0.014 |

||

|

LF(n.u.) |

Δ12 |

0.81 (0.670-0.929) |

0.86 (0.663-0.986) |

0.472 |

|

|

Δ32 |

0.82 (0.734-1.066) |

1.00 (0.743-1.072) |

0.472 |

||

|

HF(n.u.) |

Δ12 |

1.50 (1.135-2.202) |

1.44 (1.016-1.699) |

0.157 |

|

|

Δ32 |

1.18 (0.940-1.683) |

1.00 (0.890-1.552) |

0.231 |

||

|

LF/HF ratio |

Δ12 |

0.51(0.349-0.820) |

0.65 (0.402-1.136) |

0.375 |

|

|

Δ32 |

0.57 (0.413-0.970) |

1.00 (0.476-1.236) |

0.267 |

||

|

nonlinear |

SD1 |

Δ12 |

1.14 (1.008-1.340) |

1.07 (0.954-1.273) |

0.396 |

|

|

Δ32 |

1.11 (0.904-1.216) |

0.97 (0.753-1.091) |

0.199 |

|

|

SD2 |

Δ12 |

0.97 (0.824-1.190) |

0.83 (0.760-1.066) |

0.085 |

|

|

|

Δ32 |

0.94 (0.767-1.114) |

0.85 (0.7409-0.995) |

0.094 |

|

|

SD2/SD1 |

Δ12 |

0.88 (0.741-0.993) |

0.80 (0.753-0.923) |

0.184 |

|

|

|

Δ32 |

0.90 (0.752-1.064) |

0.88 (0.830-0.946) |

0.744 |

Table 3: Mean and IQR for the HRV variables.

Δ12= value prior to the film sequence divided by the value during the film sequence, Δ32=value after the film sequence divided by the value during the film sequence.

Correlations between PANAS and HRV scores and the SPQ

The total score of the SPQ was significantly correlated to a difference in NA between the EFS and the CFS (r=0.55, p=0.02) and difference between after and during the film in LF/HF ratio (r=-0.52, p=0.027).

DISCUSSION

This study found that the EFS evoked a significant response in positive and negative affect and absolute power of low frequency and the high frequency range of the heart rate variables compared to a CFS. However, the sample size of this study is small and should be interpreted with care.

The negative affect scores of the PANAS found in our study are in line with Schaefer et al., [4]. Schaefer et al., asked 364 students of a university to score 70film excerpts. An excerpt of American history X had the highest NA score, with on average 2.73, the second highest ranking film was Schindler’s list with on average 2.62. The film in our study scored a median of 3.3, indicating that the EFS evoked a negative response to the shown emotions.

The empathy measure SPQ was found to be correlated with the difference in Negative Affect (PANAS) between the two film sequences, indicating that when the EFS was shown, participants with a higher empathic trait score also showed a more negative response, measured with the NA of the PANAS. The empathy measure SPQ was also correlated with the difference of the LF/HF ratio between after and during the film. The found negative correlation indicates that people with high empathic trait scores had a lower LF/HF ratio, than people with lower empathic trait scores. The LF/HF ratio has been linked to a sympathovagal balance, with the LF related to the sympathic activity and the HF related to the vagal activity. In turn a low LF/HF ratio indicates a higher vagal or parasympathic activation. Krauth [18] also recorded a lower cardiac activity using empathic images than when umempathic images were used. However, these links to the sympathic and vagal nerve system have been criticised over the last years [19].

The protagonist of the EFS was a girl in an abusive situation, while the protagonist of the CFS was a man talking about his holiday. The difference in gender of the protagonist might have influenced the extent to which participants could empathize with the protagonist as the participants in this study were all female. Bryant [20] found that children empathise better to characters which are similar in gender or shared personal experiences than to characters which are not similar. In addition, due to the fact that only females took part in the project, it makes the results not generalizable to the general population. Furthermore, the way somebody is presented in a study may influence the level of empathy in study participants. Knowing additional information about a perpetrator (information that fosters feelings of similarity and perspective taking) increased empathy toward them, whereas knowing more about the victim did not lead to increases in empathy.

LIMITATIONS

In this study significant changes in NA scores were detected after watching the EFS, these scores were in turn correlated with the overall empathy score (SPQ). This implied that empathy was affected by watching the film, however other emotional responses were not measured and therefore further research should focus on further exploration of the effects of the films. For example, the increased negative affect scores could be the result of higher empathy or an emotional response to the traumatic events presented through the eyes of the young protagonist. A quantitative study from South Africa used self-report questionnaires to explore the psychological impact on trauma workers, specifically focusing on the level of exposure to traumatic material, level of empathy, level of perceived social support and their relation to secondary traumatic stress. It was found that previous exposure to traumatic material, level of empathy, and level of perceived social support were significantly correlated with secondary traumatic stress. Empathy emerged as a consistent moderator between the trauma workers’ previous exposure to traumatic material and secondary traumatic stress, in the way that the higher the individual`s level of empathy, the more susceptible they are to developing secondary traumatic stress.

The PANAS questionnaire used in this study was modified in such a way that the estimated emotion of the film personage was measured. This modified version was not validated and should therefore be interpreted with care.

There were differences in the Rottenberg criteria between the two films. Although duration of the film and location of data assessment were standardised, other criteria such as number of actors in the film, colour, picture motion, complexity and intensity of the film were not standardised [10]. The CFS used in this study was aimed to not elicit an empathic response, however a 4.2 score was measured on the positive affect scale of the PANAS, indicating that the participants perceived the protagonist to have a positive emotion. Others have used a test screen as a film sequence not to elicit an empathic response [10].

CONCLUSION

This study showed that the tested EFS were able to evoke an empathic response in young women. These results need to be verified by repeating this study with a larger, more representative sample, with the inclusion of more responsive and validated outcome measures. One of these measures could be the use of salivary biomarkers test that have been associated and emotions. Sequentially the film could be used to evaluate the effectiveness of empathy training in health professions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The financial support by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs and the National Foundation for Research, Technology and Development and the Christian Doppler Research Association is gratefully acknowledged. We would also like to thank the students who participated in this project and ProMente Reha, LGA and s-team solution GmbH for their financial contributions.

REFERENCES

- Cuff BMP, Brown SJ, Taylor L, Howat DJ (2016) Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review 8: 144-153.

- Ndahayo S, Mutabazi MV, Schwartzentruber A (2018) The Empathy Enigma: An Empirical Study of Decline in Empathy among Undergraduate Nursing Students. Texila international journal of nursing 4.

- Ward J, Cody J, Schaal M, Hojat M (2012) The empathy enigma: an empirical study of decline in empathy among undergraduate nursing students. J Prof Nurs 28: 34-40.

- Schaefer A, Nils F, Sanchez X, Philippot P (2010) Assessing the effectiveness of a large database of emotion-eliciting films: A new tool for emotion researchers. Cognition & Emotion 24: 1153- 1172.

- Bartolini EE (2011) Eliciting emotion with film: A stimulus set. Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Psychology dissertation. Wesleyan University, USA.

- Bednarski JD (2012) Eliciting seven discrete positive emotions using film stimuli. Doctoral dissertation, Vanderbilt University, USA.

- Forster B (2011) Spielfilm und Empathie. Thesis, Master of Philosophy, Faculty of Philological and Cultural Studies, University of Vienna, USA.

- Hoekstra M (2015) Film-elicited emotion and moral attitude. Thesis, Master of Arts, Culture and Media, University of Groningen, USA.

- Howard AL (2014) Elicitation of empathic emotions using film: development of a stimulus set. Master of Arts in Psychology dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA.

- Rottenberg J, Ray RR, Gross JJ (2007) Emotion elicitation using films. In: Coan JA, Allen JJB (Eds.). The handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Jackson PL, Brunet E, Meltzoff AN, Decety J (2006) Empathy examined through the neural mechanisms involved in imagining how I feel versus how you feel pain. Neuropsychologia 44: 752-761.

- Krauth P (2010) Kardiovaskuläre Reaktivität bei emotionalen Reizen im Zusammenhang mit Empathie. Diploma thesis Master of Science, Psychology, University Vienna, Austria.

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54: 1063-1070.

- Paulus C (2009) Der Saarbrücker Persönlichkeitsfragebogen SPF (IRI) zurmessung von empathie: psychometrische evaluation der deutschen versiondes interpersonal reactivityindex.

- Davis M (1980) A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS catalogue of Selected Documents in Psychology 10: 85.

- Davis M (1983) Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44: 113-126.

- Tarvainen MP, Lipponen J, Niskanen J, Ranta-aho PO (2019) Kubios HRV (ver. 3.3) User’s guide HRV Standard HRV Premium.

- Krauth P (2010) Kardiovaskuläre Reaktivität bei emotionalen Reizen im Zusammenhang mit Empathie. Diploma thesis Master of Science, Psychology, University Vienna, Austria.

- Heathers JAJ (2014) Everything Hertz: methodological issues in short-term frequency-domain HRV. Frontiers in Physiology 5: 177.

- Bryant K (1982) An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child Development 53: 413-425.

Citation: Janssen J, Zenzmaier C, Yap SS, Österreicher P, Simon P, et al. (2020) Validation of an Empathy Film with Health Care Students. J Altern Complement Integr Med 6: 125.

Copyright: © 2020 Jessie Janssen, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.