What Does Joy in Living Mean to Elderly Residents of Nursing Homes in Singapore? - The Full Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Swapna DayanandanS R Nathan School Of Human Development, Singapore University Of Social Sciences, Singapore 599494, Singapore

Email:swapna002@suss.edu.sg; srswapnaram@gmail.com

Abstract

This secondary publication is based on a full study to explore the meaning of Joy in Living to elderly residents of nursing homes in Singapore, the enabling and disenabling conditions to Joy in Living in nursing homes and how Person-centred Care can support Joy in Living in nursing homes. The first publication was in May 2022 based on partial data of 16 semi-structured interviews with elderly residents and six participant observations of three nursing homes (pre and post interviews) between July 2021 and November 2021. The full study is based on 25 in-depth semi-structured interviews with elderly residents and eight participant observations of five nursing homes (pre and post interview observations for first three nursing homes and post interview observation for the last two nursing homes) between July 2021 and May 2022. The concept of Joy in Living is used in the study as it is unique to an individual’s experience; The study employed hermeneutical phenomenological research methodology to allow for the exploration of Joy in Living lived experiences of elderly residents through in-depth interviews and participant observations. Seven themes for Joy in Living experiences to flourish identified in the initial analysis of the partial data remains unchanged in the full study. There is a re-ordering of the themes in the full study as follows: ‘supportive nursing home environment and practices’, ‘meaningful daily living’, ‘connectedness through meaningful relationships’, ‘fulfil the need for spiritual care’, ‘personal control’, ‘adapting to changes’ and ‘desire to be free from worries’, each of which explains a facet of Joy in Living experiences of the elderly residing in nursing homes. There is a new subtheme ‘support for forgiveness and reconciliation’ under the theme “fulfil the need for spiritual care” in the final study. These themes include the enabling and disenabling conditions to Joy in Living in nursing homes. By focusing efforts and resources on enabling the seven themes, Joy in Living experiences of elderly will flourish in nursing homes. This in turn promotes better psychosocial well-being of the elderly and better living environments where nursing home residents may enjoy satisfactory accommodation while spending their remaining years in joy.

Keywords

Adapting to changes; Elderly; Free from worries; Hermeneutical phenomenology; Joy in living; Meaningful daily living; Meaningful relationships; Nursing homes; Personal control; Supportive environment and practices; Spirituality

Introduction

Medical advancements and higher living standards have resulted in longer average life spans. These factors, combined with declining fertility rates, have resulted in an ageing population both globally and Singapore. In 2021, 16.03% of Singapore’s total resident population (citizens and permanent residents) were 65 or older: the elderly population growth increased by 7.23 per cent from 8.80% in 2009 [1]. We expect that by 2030, one in every four Singaporeans will be 65 or older [2]. The expected burden on public health care expenditure in the Intermediate and Long-Term Care Sector (ILTC) of an ageing population is exacerbated by rising chronic diseases among the elderly [3]. Several initiatives are in place to alleviate this and allow older people to ‘age-in-place’ and within their communities. However, the rush to increase capacity may not have put the elderly resident at the centre of nursing home service design and delivery. Basu [4] noted that the elderly residents are cramped in the living quarters. Singaporeans have a negative perception of nursing home services. A qualitative study was conducted in 2015 among people aged 50 years and above on perceptions and attitudes regarding ILTC. It entailed one-on-one interviews with care recipients and their primary caregivers using various eldercare services available in Singapore, including nursing home services. Based on 30% of the interviews, the study discovered that nursing homes “neglect patients and restrict freedom cut across the responses of both users and nonusers of nursing homes, and their caregivers”. People mostly used nursing homes when their primary caregivers were unavailable. Despite this, the quality of care in nursing homes has improved dramatically since 2016 because of several initiatives by government agencies, Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) and the Ministry of Health (MOH), such as the Licensing Terms and Conditions on Enhanced Nursing Home Standards under the Private Hospitals and Medical Clinics Act.

A review of gerontological literature shows a gap in studies that focus on the joy experienced by elderly nursing home residents. Despite this, key findings indicate that holistic care models such as Person-centred Care [5], variations of person-centred care like Person-directed Care [6], Eden Alternative Model [7], and the Biopsychosocial Model of Health and Illness [8], have a positive impact on the well-being of the elderly in nursing homes. The impact of the care models on quality of care, quality of life, well-being, elderly satisfaction with services, and staff satisfaction working in nursing homes, is ‘measured’/assessed, with some reference to concepts of happiness and a Good Life, but little attention is paid to the joy experienced by care recipients.

Quality of life is defined as a “multi-dimensional construct with objective and subjective constructs, although the latter is often given greater priority” by Wang et al., [9]. Functional status is an example of an objective construct that can be measured using assessment instruments such as the Barthel scale. There is no consensus on a common definition for the subjective construct of quality of life, comprising but not limited to autonomy, enjoyment, employment and income, family relationships, meaningful endeavours, spiritual well-being and social support, according to Chaturvedi and Muliyala [10]. Well-being, compared to the quality of life, looks only at subjective attributes and has been measured by ‘happiness’ i.e., emotional reaction and ‘satisfaction’ i.e., cognitive evaluation of life, in studies on well-being [11]. According to Rinnan et al., [12] (p. 1469), “Well-being corresponds to processes where people perceive a good life based on their own merits and might be described as comprising joy, enjoyment, fulfilment, pleasure, satisfaction, happiness, involving elements as relationships with family and a sense of community”.

Is it possible to live a good life in old age? Do we have to say goodbye to the positive emotions of happiness as we age? Carstensen et al., [13] used “experience-sampling to examine the developmental course of emotional experience in a representative sample of adults spanning early to very late adulthood” (p. 21) for a one-week period that was repeated five and then ten years later in a Stanford study. Participants were given pagers and were required to respond to questions as soon as they were paged during the one week. They were asked how happy, satisfied, and comfortable they were. A key study finding is an improvement in emotional experience from early adulthood to old age, which, while contradicting common stereotypes about ageing, is consistent with the Selection, Optimisation, and Compensation (SOC) model of adult development [14]. The dynamic SOC model is a successful ageing theory that views ageing from early adulthood to old age as a life course of developmental change. The elderly can be content and live happy lives by being ‘selective’ in investing time and resources in goals and leveraging their expertise to ‘optimise’ performance in specific areas to ‘compensate’ for losses or limitations brought on by the ageing process.

Life course theory allows for the analysis of people’s lives within structural, social, cultural, and historical contexts across the four stages of the life course: childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age [15], and Erikson's [16] eight psychosocial stages of lifespan development, with a crisis of ‘integrity versus despair’ at the final stage of life, are invariably mentioned in studies on ageing. Two qualitative studies, one in the United Kingdom and one in Australia, have been conducted to investigate the Good Life concept of seniors living in care facilities [17-19]. According to Minney and Ranzijn [19], Good Life “encompasses both the value of one’s life and well-being in general” (2016, p. 919). Both well-being and Good Life, which are subjective constructs, have a value component, i.e., the person evaluates his life and provides an assessment of it. The quality of life construct, on the other hand, has both objective and subjective attributes that are independent of an individual's assessment of ‘quality’.

So, what about Joy? Joy stems from things that have more intrinsic value (for example, the belief that one has a purpose in life) and being happy in the face of losses such as loss of physical functioning, which results in poor health, loss of income from retirement, and even loss of a loved one. For those over the age of 70, the integrative process is critical for inner contentment, harmony, and joy based on one's values, life purpose, meaning and religious beliefs [20]. Because of the impending reality of death, people frequently ask existential questions as they grow older. In this sense, Joy can be seen as a step beyond Good Life.

A qualitative study was carried out to determine the essence of Joy of Life for elderly residents of Norwegian nursing homes [12]. In that study, the researchers employed the concept of Joy of Life, a multidimensional construct “that appears more closely related to subjective well-being commonly defined in social science as the absence of negative emotions, the presence of positive emotions, and life satisfaction, all of which corresponding to the concept of flourishing” [12]. Inspired by these studies in other countries, and the findings of local quantitative studies on nursing homes that psychosocial well-being is not being addressed, I have modified and narrowed down on a concept that I believe is relevant to the Singapore context. In this study, the concept of Joy in Living is used instead of Joy of Life because it has a strong applied focus and, in my opinion, a concept that is ‘dynamic’ and operationalised in concrete terms would be easier for Singapore nursing home residents to understand. So, I developed the concept of Joy in Living, which is rooted in the present and includes physical, psychosocial and spiritual dimensions. By researching this concept, I hope to add another dimension to holistic approaches to care in Singapore nursing homes.

There are no hypotheses for this study, instead there are four research questions to guide the study as follows:

- What does Joy in Living mean to elderly residents of nursing homes in Singapore?

- What are the enabling conditions that are conducive for Joy in Living in nursing homes?

- What are the disenabling conditions that are not conducive for Joy in Living in nursing homes?

- How does Person-centred Care support Joy in Living in nursing homes?

Materials and Methods

Design

The hermeneutical phenomenological research methodology is used for the study that depends heavily on research participants -the elderly in nursing homes- recalling their lived experiences in those homes and reflecting critically on the meaning they ascribe to Joy in Living [21]. The researcher conducting this study is part of the study to interpret and identify the essences of each lived experience, the meaning ascribed to Joy in Living, and find the language to convey the essences of the data collected and analysed. There are six research activities that provide the methodological structure of phenomenological research studies [22]. This qualitative study was conducted between July 2021 and May 2022. This study is based on 25 in-depth semi-structured interviews with elderly residents and eight participant observations of five nursing homes (pre and post interview observations for first three nursing homes and post interview observation for the last two nursing homes).

Participants

A total of 25 elderly participants were selected from five nursing homes: two homes with more than 300 beds but less than 500 beds and the other three homes with more than 100 beds but less than 300 beds. Inclusion criteria were participants being 65 years and above of age, residing in the nursing home for at least one year, a Singapore citizen or permanent resident in Singapore, ability to understand and speak in basic English. Bed-bound and residents with dementia, as assessed by the nursing home, were excluded.

Data collection

The data collection methods in this study are in-depth individual face-to-face interviews with elderly research participants using semi-structured interview guide and running records of onsite observations as a participant observer. The concept of Joy in Living was introduced to the participants at the start of the interview and in the Participant Information Sheet given to all participants. The following topics were covered in the interview:

- Participants’ background and why they are in a nursing home

- Participants’ day-to-day living experience in the nursing home

- Participants’ religious/spiritual beliefs, their belief system and purpose in life

- Participants’ understanding of Joy in Living, their views whether Joy in Living is possible in a nursing home and why if their answer is either yes or no

- If participants are living a joyful life in the nursing home, what are the things contributing to it and vice versa

Eight onsite participant observations were conducted at the five nursing homes. Only one observation session was conducted at the last two nursing homes each due to the evolving COVID-19 situation during the data collection phase of the study. Each observation session was eight hours that was either conducted over one day with an hour’s break in between the am and pm sessions or half days over two days. There was an interruption to data collection through face-to-face interviews and onsite observations for about two months from mid-September 2021 to mid-November 2021 and January 2022 to March 2022 due to development of COVID-19 clusters in a few nursing homes and the national policy response to suspend in-person visits to nursing homes. To allow for operational flexibility given the evolving COVID-19 situation and emergence of ‘Omicron’ new COVID-19 variant detected in December 21, interviews were conducted over ‘Zoom’ online platform with video function from middle of September 2021 onwards.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted after collection of data from each nursing home, where Joy in Living was used as the analytical concept for the analysis of the data to identify ‘significant statements’ and ‘clusters of meaning’ about Joy in Living from the transcripts of interview and observation audio records. The thematic statements chosen were those phrases that seemed to particularly allude to the Joy in Living experiences [22]. In hermeneutical phenomenological studies, van Manen [22] offered three methods: (i) wholistic approach; (ii) a selective approach; and (iii) the detailed or line-by-line approach for identifying themes during data analysis. These approaches can be used to discover themes or facets of a pattern of the phenomenon across datasets. As the wholistic and selective methods do not detail out the step-by-step process to conduct data analysis, the first author applied the phases of Reflexive Thematic Analysis [23,24] to guide the process.

Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) is compatible with hermeneutical phenomenological studies as it is “about the researcher’s reflective and thoughtful engagement with their data and their reflexive and thoughtful engagement with the analytic process”, and the first author has conceptualized themes “as patterns of shared meaning underpinned or united by a core concept (we later conceptualized this as a ‘central organizing concept’ . . . ” ([25], pp. 593-594). Before commencement of data analysis, the transcripts were read several times to aid recall and familiarity with the content by immersing in the data. During data analysis, NVivo-Windows January 2022 Release 1.6 (NVivo) software was used. NVivo was used to document the ‘significant statements’ as ‘codes’, i.e., a short phrase to describe what is said in the elderly interview and the observation transcripts, gather all the quotes that were carefully tagged to the codes, and identify ‘clusters of meaning’ as higher-order conceptual ‘themes’ to answer the research questions [22,23,26]. NVivo was used to handle and analyse the different types of data from the research study, e.g., field notes, transcripts of the interview, and the observation audio recordings and photographs of objects, environment, and activities with faces of people obscured.

To strengthen research rigour, the interview and observation guides were piloted in a nursing home that was not included in the study, and data were collected and analysed through methodological triangulation. In the pilot study, where the elderly participant required clarification, prompts were added to the interview questionnaire (e.g., prompts were added to the questions on belief system and purpose of life).

Results

|

Name of Resident |

Gender |

Ethnicity |

Length of Stay |

|

Nursing Home A |

|||

|

A1 |

Female |

Indian |

3 - 5 years |

|

A2 |

Male |

Chinese |

1 - 2 years |

|

A3 |

Male |

Chinese |

1 - 2 years |

|

A4 |

Male |

Chinese |

1 - 2 years |

|

A5 |

Male |

Chinese |

>5 years |

|

Nursing Home B |

|||

|

B1 |

Female |

Chinese |

3 - 5 years |

|

B2 |

Female |

Chinese |

>5 years |

|

B3 |

Male |

Chinese |

3 - 5 years |

|

B4 |

Male |

Chinese |

1 - 2 years |

|

B5 |

Male |

Eurasian |

3 - 5 years |

|

Nursing Home C |

|||

|

C1 |

Male |

Chinese |

Over 5 years |

|

C2 |

Male |

Chinese |

1 - 2 years |

|

C3 |

Male |

Chinese |

1 - 2 years |

|

C4 |

Male |

Indian |

3 - 5 years |

|

C5 |

Male |

Indian |

3 - 5 years |

|

C6 |

Male |

Malay |

3 - 5 years |

|

Nursing Home D |

|||

|

D1 |

Male |

Indian |

3 - 5 years |

|

D2 |

Male |

Chinese |

3 - 5 years |

|

D3 |

Female |

Chinese |

1 - 2 years |

|

D4 |

Female |

Chinese |

3 - 5 years |

|

Nursing Home E |

|||

|

E1 |

Male |

Indian |

3 - 5 years |

|

E2 |

Female |

Indian |

1 - 2 years |

|

E3 |

Female |

Chinese |

3 - 5 years |

|

E4 |

Male |

Chinese |

>5 years |

|

E5 |

Male |

Chinese |

>5 years |

Table 1: Profile of the 25 participants.

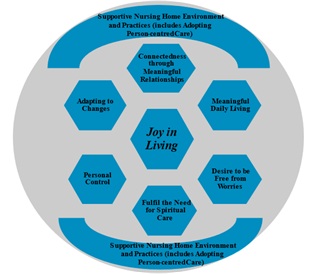

Seven themes emerged as important for Joy in Living experiences of elderly to flourish in nursing homes: (i) ‘supportive nursing home environment and practices’ that includes adopting person-centred care, (ii) ‘meaningful daily living’, (iii) ‘connectedness through meaningful relationships’, (iv) ‘fulfil the need for spiritual care’, (v) ‘personal control’, (vi) ‘adapting to changes’ and (vii) ‘desire to be free from worries’. These themes include the enabling and disenabling conditions to Joy in Living in nursing homes and, are the common essences of participants lived experience in a nursing home, as narrated by them through reflection of their day-to-day personal experiences [27]. These themes, when enabled, promote Joy in Living experiences of the elderly residing in nursing homes as illustrated in figure 1. The themes and sub-themes are elaborated in table A1 in appendix A.

Figure 1: Themes for Joy in Living experiences in nursing homes.

Figure 1: Themes for Joy in Living experiences in nursing homes.

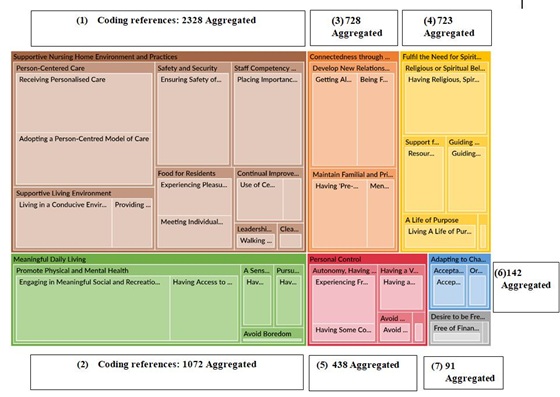

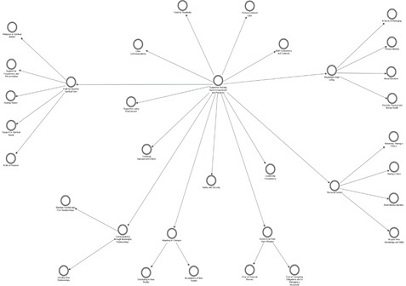

The hierarchy chart in figure 2 shows the frequency of reference to the themes, subthemes, and codes in the transcripts of the interview and the observation audio recordings in the NVivo software. The subthemes within each theme are as illustrated in the concept map in figure 3.

Figure 2: The hierarchy chart shows the frequency of reference to the themes, subthemes, and codes in the transcripts of the interview and the observation audio recordings.

Figure 2: The hierarchy chart shows the frequency of reference to the themes, subthemes, and codes in the transcripts of the interview and the observation audio recordings.

Figure 3: Concept map of the themes and sub-themes for Joy in Living experiences in nursing homes.

Figure 3: Concept map of the themes and sub-themes for Joy in Living experiences in nursing homes.

Results of theme 1 - Supportive nursing home environment and practices

The foundational theme that provides the conducive ecosystem for Joy in Living experiences to flourish is a ‘supportive nursing home environment and practices’, which include the adoption of Person-centred Care approaches such as the Person-centred Care Model or its variations in Person-directed Care or Eden Alternative Model. This ecosystem theme contains eight sub-themes, which are presented in descending order of coding frequency: (i) person-centered care; (ii) supportive living environment; (iii) safety and security; (iv) staff competency and capability; (v) food for residents; (vi) continual improvement efforts; (vii) leadership competency; and (viii) clear communications. The sub-themes address various aspects of the ‘supportive nursing home environment and practices’. This theme has the most coding references, as shown in figure 2 on the coding references in the NVivo software hierarchy chart. All participants emphasised the significance of at least one of the sub-themes in creating an environment conducive to Joy in Living experiences flourishing. This was also supported by the observational data.

Person-centred care

Person-centred Care’s psychosocial dimensions are covered in the following themes: ‘meaningful daily living’ and ‘connectedness through meaningful relationships’. This section discusses individualised nursing care for residents. Personalised nursing care for residents was observed in all five nursing homes, including grooming, medication administration, monitoring, assisted feeding, and support at group activities and exercises. However, staff engagement with residents is patchy across the five nursing homes and appears to be dependent on the personal qualities of the staff involved and their ability to communicate in vernacular languages: rather than a consistent practice across all staff interactions.

The Therapy Assistant is sitting next to her and stroking her hair. She speaks to the resident in a Chinese dialect. The Therapy Assistant, who is a local Chinese and a mature staff in either her late forties or fifties, smiles at me and says she is speaking to the resident in (1st Observation at Nursing Home A)

Staff who are assisting to feed the residents are patient and they encourage the residents to finish their dinner. Beyond this, staff do not engage in small talks with the residents. Their focus is on the task of feeding the residents safely. Staff 4 speaks to the residents in dialect and these residents interact and engage with her more when compared to residents assisted by foreign staff… Staff 3 is an Indian PR staff. She speaks Tamil and English. She engages the Indian residents by speaking to them in Tamil (Post-interview Observation at Nursing Home E)

A total of 20 out of 25 participants, or 80%, reported receiving personalised nursing care in the aforementioned areas. One resident expressed her confidence in the nursing home's care.

“Because I feel that I come here is suit for me. I got the thinking that somebody can look <after> me until old.” (B1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

Two residents expressed dissatisfaction with the personalised nursing care they received.

“Sometimes they neglect or extend the time for changing the diapers. It is not done correctly at the correct timing. They delay for 30 minutes, 40 minutes. Like this morning for example I tell you, my diaper was changed at 12.30 and now it is 5 o’clock. So, I have been wearing this for the last 7 hours or 6 and a half hours. It is quite uncomfortable you know.” (D1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

“Sometimes they see you, I call to help me. They just walk away. Some say, “I don't know.” (E3, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

According to the other three residents, because they are not wheelchair-bound, their nursing care needs are minimal: only medication and health monitoring. Showers being too short were mentioned in interviews with three participants from the last two nursing homes. The preliminary data collected from the first three nursing homes did not reveal this.

“The shower is too... too short you know. They... just... they should know that we are not happy about the shower. They should know by now…” (D1 Length of Stay: 3 - 5 years, Male, Indian)

“Because sometimes they shower me so quickly like that 10 minute like that quickly. Sometimes I put soap haven’t finish here they want to say okay, okay, finish, finish. How can like that? My body got soap some more how can.” (E1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

Another insight that came up in interviews with four participants from the last two nursing homes (especially in Nursing Home D) was the over-reliance on use of adult diapers to assisted toileting. Adult diaper users reported no attempts by the nursing home to wean them off diaper use.

“At home, I go toilet. Here I wear pampers. Wear diapers, there are advantages and disadvantages. You wear pampers; you don’t need to walk to toilet. The disadvantage, there is no exercise. Life is like that, there are advantages and disadvantages. Like ten fingers, some short, some long, they are all not the same. There are advantage and disadvantage.” (D4, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

“Even before I go to toilet, they already have diapers. And they tell you what for go to toilet, you are wearing diapers? To me no difference ‘lah’ <simplest and most common Singlish expression like ‘yeah mate’ in Australia>. Yeah, I say I use the diapers ‘lah’ like everybody. Because in the room there is only five of us, they say there is no need to tell, no need to tell us whether to go to toilet or not.” (E5, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

During a post-interview observation session at Nursing Home E, one of the assistant nurse managers hinted that there is still room for improvement in this area of nursing care. She told the first author in an impromptu conversation that with the relaxation of COVID-19 safety protocols, which will free up staff time, the home will proactively identify residents who are ready to be weaned off diapers in the coming months.

Supportive living environment

A well-designed physical environment can ensure the elderly’s safety and independence in either the community or nursing homes, which has a positive impact on their well-being. Environmental aspects of supporting Person-centred Care delivery, conducting social and physical activities, and creating a home-like ambience must be considered when designing nursing home living spaces. In their pioneering work on the ecological model of ageing, Lawton and Nahemow [28] emphasised the importance of having physical spaces that fit the needs of the occupants for optimal functioning. Several studies over the last two decades have also emphasised the importance of physical environment accessibility on senior functioning [29-31].

The living environment was mentioned as an aspect of the nursing home that nine out of 25 participants, or slightly more than one-third of the participants, liked. One of them chose the nursing home based on her impressions of the living environment and amenities when she visited it before making a decision.

“…peaceful. I don’t how when I see the picture I know I want. My friend gave me the picture of the building. I went to other homes, but I cannot suit, then I see this I like. My sister also say better, this one also nice…They got proper place. All the sleeping place they have water, put water for drinking at hall.” (B1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

“I like the garden… I feel happy in my heart when I hear the water, birds and <see> fish swimming... I also pray there, give me joy.” (C6, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Malay)

Two residents expressed dissatisfaction with their living environment.

“This building is not properly maintained. It’s dirty. Look at all the fence, never clean. Compared to the old place, every week somebody will come clean all the fence.” (A4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“…usually at night in the morning about 3 am the sleep is disturbed because, yeah, they’re changing. The staff is changing all the patients’ diapers because the diapers got too much urine and they are, it becomes soggy and wet. So, they start changing. So, when they start changing, there's quite a bit of noise… Dementia, and some of them are making noise at night. Some of them making noise at daytime, shouting at times.” (D1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

At the second observation session at Nursing Home A, the first author encountered rodent infestation problem in one of the bedrooms during an impromptu conversation with a resident in his six-bedder ward. She saw a rat trap kept at the foot of the cupboard. The cupboard was not in a good condition. Rat infestation is a safety concern too.

“This is not as bad as the rats... I got a lot of things, so they say you cannot put on the floor and all that, so they gave but they gave one that’s broken <they gave him a cupboard>. And rats used to go in what from the back. Now they say they fix it.” (A5, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese; during an Impromptu Conversation at the 2nd Observation Session at Nursing Home A)

The first author also observed a hygiene problem with birds flying in during mealtimes and in the wards of three nursing homes. These nursing homes are set in open garden compounds that are popular with birds. This is a concern because birds’ droppings can spread diseases. Staff is constantly on the lookout for birds and promptly clean up food waste and spills. The rest had nothing negative to say; however, seven participants, or slightly more than a quarter of them, wished for the temporary COVID-19 safe distancing measures to be lifted as soon as possible. The zoning has limited their access to the nursing home's entire compound and amenities, as well as group activities with other residents from different zones, volunteer-led activities, outings, and frequent visits from family and friends.

“Yeah. It’s downstairs. There’s a fishpond and everything. Before we used to go down every day. We’ll go down, see the fish, then we all cannot...Now cannot because the COVID-19. We are not supposed to go down, leave our dormitories.” (C5, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

“Last time ‘ah’ before this Covid, last time got drawing class ah, got singing ah, go down ‘ah’. Now all don't have, so quiet.” (D3, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Female, Chinese).

Safety and security

Observation sessions were primarily used to identify safety and security practices. One caveat is that many of the observed safety practices are Covid-19 temporary safety measures in place during the observation data collection phase. Staff at all five nursing homes were observed following internal safety protocols when administering medication, supervising residents during group exercises or mealtimes, feeding special diets, and transferring residents from bed to wheelchair/geriatric chair and vice versa. In Nursing Homes A, B, C, and D, I observed that fall prevention is a key focus, and there is an over-reliance on the use of restraints on several elderly in beds, wheelchairs and geriatric chairs. Only Nursing Home E reported using restraints as a last resort, which was corroborated during the observation session.

“No restrain here, only hand mittens if they scratch themselves. But they move and follow us sometimes, look at the work nurses do. Keep them occupied, until they quiet. Sometimes, give them something to do to keep them occupied. But must ensure environment is safety.” (Impromptu Conversation with a staff at Post-interview Observation at Nursing Home E)

She asks the residents for their names, refers to a medical records ‘IMR’ folder with residents’ names and their laminated photographs, before giving the medicines. The medication trolley is a mobile cabinet with mini drawers. The mini drawers have names and photos of the residents. The medicines are kept in the mini drawers. (1st Observation at Nursing Home A)

A consistent practice in all the meal observations is having dedicated staff moving around and watching over residents who are eating on their own in both the living and dining rooms. Staff also go around with a pair of scissors to cut the vegetables and meat to smaller pieces for those who ask for assistance or look like they are struggling with their meals. (2nd Observation at Nursing Home B)

Four participants reported falls in the nursing home that fortunately did not result in bone fractures. Two participants reported falls by other residents: one of which resulted in the resident’s death.

“The other day one man died, he fell off the wheelchair and hit his head. This man, I predicted a long time ago. So, nurse ask me why you talk like that. I said if you look, he goes to the toilet 20 times. So, he’s putting himself in danger. You as nurses need to make sure he keeps safe; they don’t lock the wheelchair. I said I fall never mind, but when he falls and there’s nobody around. That’s the danger.” (A4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

Staff competency and capability

19 of the 25 participants, or slightly more than three-quarters reported both positive and negative experiences with various staff members. Negative experiences occurred as a result of staff lacking the necessary knowledge, soft skills, and language barrier (for foreign staff) to carry out their duties effectively. This was exacerbated further by staff workload and/or inadequate staffing.

“Some nurses are very observant. Some, not so... I speak frankly, sometimes they are very busy and some of them, they don’t bother.” (A4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“A few is very good. They really do the job, they very follow the procedure. Like from bed transfer to this, they really take care of you. Some they just stand down there, like for my case I used to use slide board and slide to my wheelchair. Some stand behind look at you. Anytime I can miss out and I fell down. They just stand down there. Some really good ‘lah’ they take my two legs then I slide over very fast. One second. I think less than 20 seconds I go there already. Some they sit down there and slowly do. Some of the nurses they really use their heart to work, some they just are not really nice.” (A3, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“… like I said, a lot of staff cannot communicate, and different mentality… most of them are quite busy… So, they have to be more relaxed to be able to talk to us, at the same time, it is a balance that they cannot be too relaxed and not get things done.” (B4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese).

“Do long hours, they must also rest. Every morning come to work, can see the face look tired, not enough sleep... Yeah, yeah. They can look after us properly <if they are rested>. (E2, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Female, Indian)

“There are some nurses, they didn’t do properly. Although they say they very good to me, but anyway, there are too many here didn’t do properly, say “wait, wait”, then wait very long didn’t do. So, if there are things I can do on my own, I do. Although they are friendly.” (E4, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

Three of the participants expressed their dissatisfaction with staff turnover. One of them mentioned how he misses the staff who used to do his physiotherapy sessions but are no longer with the nursing home. Another resident reported frequent staff changes because of attrition.

“They got their problem about the work. How many people go out, already don’t work here.” (B1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

During two nursing home observation sessions, I observed daily shift handover meetings to share updates with the care team taking over. Staff at all five nursing homes were observed following internal protocols when carrying out their duties. For example, only nursing aides, enrolled nurses, and above feed pureed food to residents at risk of choking and do nasogastric tube feeding for bedbound residents. During one observation session at a nursing home, I observed that staff do not intervene to defuse sporadic arguments among residents. I struck up an impromptu conversation with another resident who had witnessed the incident.

“Some can, some they will leave them. Because ‘aiya’, I don’t want to say anything because it’s not good. Sometimes nurse and all got visitors, special visitors, if no visitors, then you can see shouting.” (Impromptu Conversation during 2nd Observation Session at Nursing Home C)

Observation data were collected in the last two nursing homes when COVID-19 measures were significantly eased. During one of these post-interview observation sessions, a senior nursing staff member shared that the increased workload of the nursing team from implementing COVID-19 safety protocols had left little time for the nursing department to work on improvement projects over the last two years. She believes that with the relaxation of COVID-19 measures, there will be more room to strengthen core nursing practices and implement progressive ones.

“During these 2 years with Covid, we are very constrained. So, frankly speaking, we also need to tighten our nursing care. A lot of staff is down with Covid, isolated, we are very short. So certain things we are neglect, so it is a lack. Now slowly we must ‘die die’ <Singlish phrase that it is a must have even if you have to die for it> even if like war zone like that. Our environment, we are very keen in learning, but just open only our lockdown and busy with the NOK visits. We have this programme but somehow just dropped, so must pick up now. Some of our residents are mobile and shouldn’t need to wear diapers. We should encourage them to wean off.” (Impromptu Conversation with an Assistant Nurse Manager at Post-interview Observation at Nursing Home E)

Food for residents

There is a wealth of literature on nutrition for the elderly in hospital and nursing home settings, with a focus on the risks of malnutrition and the causes of decreased appetite in the elderly [32-35]. There is, however, less literature and research on the association of food with memories in the elderly. It is not uncommon for someone to eat food at a party and be transported back to a pleasant or unpleasant memory associated with that particular dish eaten in the past. Chinnakkaruppan et al., [36] conducted an intriguing neurological study on laboratory mice and discovered a link between the brain regions responsible for taste memory and remembering the time and location when the taste was experienced. In addition to this individualised preference and enjoyment of food, elderly people from various ethnic communities have different palates shaped by their cultural heritage and unique dietary restrictions such as consuming only halal or vegetarian meals or being vegetarian on certain days of the week. Because of food allergies and dietary restrictions, some elderly people may need to avoid certain foods.

12 of the 25 participants, or approximately 50%, complained about the quality of the food or food served that did not meet their dietary preferences.

“The Chinese one cancelled already. Sometimes got babi <pork>, don’t want. “Now, Malay food. Sometimes can, sometimes cannot. I mean, last time one, the Tuesday 'ah', the Muslim food, they give me chicken. I vegetarian Tuesday and Friday. Eat rice and vegetable only. Last time I like, one staff Indian cook ‘resam’ <a spicy Indian soup dish>, curry in kitchen give me. Missy <nurse> say cannot, my sugar, eat food they give, cannot special.” (A1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Indian)

“But I like meat, not fish. When I’m outside I always want some meat. When I’m here I got no choice.” (A2, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“Not quite like. Chinese food or any food must be hot. Cold, cold <now>”. (D3, Length of Stay: - 1-2 years, Female, Chinese)

Sometimes the food is very tasty. But sometimes, I don't know why the xxx nursing home give me like this kind of food, I don't like. Yeah, I think the meat I must say all, certain meat, I like pork but too hard. And then sometimes, some food, the rice all hard then I eat potato to help me substitute the rice. Difficult to chew, difficult to bite. The chicken also no taste, hard to bite. (E4, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

Two participants expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of food served. When I asked if they had asked for a second helping, one participant said he was embarrassed to ask “Shame”, and the other said staff would be upset if she used the call bell unnecessarily to request more breakfast.

Four participants reported being “okay with the food” or having “no complaints”, with one participant sharing that, in addition to being okay with the food, he is grateful to God for the food received. Two participants made no remarks about the food. Five participants stated that the food is good and that they enjoy it.

“We all have ‘uh’, three, three meals a day. So that's enough for us what. I don't need much”. (D2, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Chinese)

“<Mee Tai Mak - a Chinese dish> Too watery; when I eat the water all come out. I like they fry here… Pork. Mostly is pork. Chicken also give. Fish is very good, there is no bone, else we have to be careful of the bone.” (D4, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese).

Continual improvement efforts

All five nursing homes were found to have implemented centralised services such as central kitchens for in-house meal preparation and a central laundry service for all wards. Nursing Homes A and D have implemented technologies such as an automated guided vehicle (i.e., an autonomous robot) for food delivery, while Nursing Home C cleans the dining hall floors with an automated steam machine. To increase staff productivity and protect them from back injuries, Nursing Home E uses a ceiling hoist to transfer bedbound residents to bath trolleys for showers.

Nursing Home E also employs technology to improve the service delivery experience for its residents, such as the use of an ambulatory hoist and forearm rollator for wheelchair-bound residents' walking exercises and specially designed ‘Gym Tonic’ low-intensity strength training exercise equipment for residents’ use. During an observation session at Nursing Home A, I observed an innovative programme for dementia residents called ‘Mini Mart’ in one of their residential living areas. Residents earn fake money by participating in exercise activities, which they can then use to redeem snacks like potato chips and cup noodles on their ‘shopping trip’ to a ‘mini-mart’. Residents must count the counterfeit money and coins to pay the exact amount indicated on the food items displayed on the shelves in the ‘mini mart’ room. The ‘mini mart’ room is styled after a supermarket.

I observed a group of ten residents, each with a ‘maracas’ musical instrument, exercising, singing along, and shaking their ‘maracas’ to music videos being played on TV during an observation session at Nursing Home E. Residents are rewarded with a fake currency that they can keep in their wallets and use to ‘buy’ snacks and other grooming necessities at fun fairs/‘Bazaars’ (which have now become mobile ‘Bazaars’ because of COVID-19 safety measures). Playing online digital games on tablets, playing ‘Bingo’, and learning to play the keyboard are all examples of ‘Hope Kee’ activities.

Leadership competency

Positive leadership role modelling was observed at Nursing Homes B and E and gleaned from impromptu conversations at Nursing Homes A and D.

At the briefing at the female ward, staff nurse informed the Chief Executive (CE) that there was a new resident who was a little unhappy and having adjustment problem. CE walks over to the ward to speak to the new resident. CE returns shortly after her chat with the new resident. Apparently, according to the home protocol, the resident needs to be isolated for seven days before she can mingle with the rest of the residents at the common areas. She is bored. CE asks staff to give her an iPad to let her watch whatever shows she wishes to watch. A staff quickly follows up on this. (1st Observation at Nursing Home B)

“I know about this one <referring to the vacancy at Nursing Home A> because of the certificate course that * xxx <CE> teach. The trainer is xxx <CE> herself…Yeah, she trains us hopefully we’ll join this company but not all will join ‘lah’.” (Impromptu Conversation at 2nd Observation at Nursing Home A)

* To protect the identity of CE, name of CE is replaced with xxx

After updating on residents’ progress, the Assistant Nurse Manager briefs all present on AIC <Agency for Integrated Care> project updates on wound management and enabling identified residents to wean off diaper use. Project team members take turns to provide updates on the progress of their projects and next steps planned. The Assistant Nurse Manager wrapped up the meeting by asking staff for feedback. Overall, there is good interaction and participation from staff present. (Post-interview Observation at Nursing Home E)

Two residents expressed satisfaction with management’s support for feedback and gathering residents’ wishes beyond daily nursing needs to include preferred funeral arrangements.

“Some more the management is a support me. Support by need anything they are going to help me. Because they interview me. Sometimes they got interview me. They ask anything, anything I want. Then I tell them, I want this, I want that.” (E1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

Five residents, or 20% of the residents expressed strong opinions that management does not provide direction and leadership for the organisation and its staff.

“…the food, all you need to do is to get somebody to do quality control. You’re paying for the food …But if you don’t bother about it, they will just give you the same and this is exactly what is happening.” (A5, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

“They understand, most of the nurses very intelligent. They understand, the only thing is they got no power to say must have this, the patient must have that.” (D3, Length of Stay - 1-2 years, Female, Chinese, a former nurse)

“They don’t agree ‘lah’ <for a slightly longer shower>. I think it’s the boss’s idea. Yeah. Because they have to get back to work.” (E5, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

The study did not include any staff interviews or focus groups. However, during an impromptu conversation with a staff member during an observation session, the staff member alluded to a culture in which staff are not encouraged to express their opinions and provide feedback for improvement.

Observer:

“Have you given this feedback to the management?”

Staff:

“I’m not sure cos I just joined here. But I don’t like to highlight, this is not my portfolio I mean the <*xxx designation> is the lowest level here. Because we cannot understand that, we cannot do.” ( Impromptu Conversation at (2nd Observation at Nursing Home A)

*To protect the identity of staff and organisation, designation is replaced with xxx

Clear communications

There appears to be miscommunication and misunderstanding of COVID-19 restrictions on next-of-kin visits and certain nursing home policies based on the sharing of seven participants at interviews, i.e., slightly more than a quarter of them, and an impromptu conversation at an observation session.

Resident:

“How long, when can I see family? When allow from MOH side?”

Observer:

“I think soon because it’s been too long already. The government intends to allow visits to hospitals and nursing homes from 21st Nov onwards. This is what is announced in the newspapers and TV news.” The resident is relieved to hear this. (Impromptu Conversation during (2nd Observation at Nursing Home C)

“I think have <books, magazines> but I never know that there is got newspaper. Hospital have <communications gap as resident is unaware whether newspapers are available>. (D3, Length of Stay: - 1-2 years, Female, Chinese)

“What can I do <when asked if there are opportunities for her to volunteer her services>? So many people work here, I do what, right?” (E3, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese; from the post-interview observation session, it was observed that there are opportunities for residents to volunteer in the home. It is likely a communication gap as resident is unaware)

Two previous incarcerated residents shared that the nursing home does not allow visitors; only family members are permitted to visit them. This is not the lived experience of other nursing home residents who have reported having friends visit them. This could be a request made to the nursing home by family members to prevent access to friends from their ‘shady’ pasts.

“Have a friend but they never come and visit me. The Nursing Home E no allow, not allowed to visit me, anybody. Nobody can visit me. Except my brother and sister-in-law. Because the Nursing Home E is a very strict place. Yeah. Correct <covid restrictions>. Second thing Nursing Home E, they got some law here. Sometimes they <his friends> not allowed to see me. Other residents I don’t know. But the law is same. Same law. Everybody. Not just for me.” (E1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

Two residents stated that they were aware of the COVID-19 restrictions and their implications.

“Yeah, of course. Only now only cannot. Now, there are some restrictions. I just cannot move around, and food is definitely not allowed. Before no problem, I am allowed to bring food, but not now.” (D2, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Chinese)

Results of theme 2 - Meaningful daily living

Participation in social and group recreational activities for seniors has been shown in studies to facilitate the development of new relationships, keep them meaningfully engaged, and promote physical and mental health [12,18,19,37].

Promote physical and mental health

The vast majority of participants, 20 out of 25 (or 80%), reported that there were very few meaningful activities in nursing homes other than structured physical and occupational therapy exercises for residents.

“I go swimming you know. Here in the home.” (A1, Length of Stay: 3–5 years, Female, Indian)

“I do join the group exercise. It is good for my strength. I like the individual therapy better.” (A4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

The activities include stacking and rearranging cups, identifying matching items in 3-d game sets, completing jigsaw puzzles and colouring pre-printed drawings. One staff… walks around and supervises the residents…. For selected residents, he works on the range of motion of their upper limbs: the arm, forearm, and hands, while they are working on their assigned tasks. (1st Observation at Nursing Home C)

Nursing Home E is home to four of the five participants who reported meaningful activities organised for them (including opportunities to volunteer their services). This was also supported by the Nursing Home E observation data.

“Play carrom, uno, card, got so many ‘lah’ I forget. We start after drink coffee already 2 o’clock. Dinner time is four o'clock. Before dinner, ten minute, half hour like that we stop ‘lah’, 3.45 like that… Here got the cloth folding all I like… Here, okay ‘lah’ they all close that's why I say fold the cloth, fold plastic bag, game also passing time. So never think the family, missing them, rest the mind. And give coloring they give picture, I get first prize.” (E2, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Female, Indian)

“Okay. I'm happy, I am happy with all the things here. As you can see, I like ‘Hope Kee’ very much… singing, sing songs, I like to sing, then after exercise, they play game. Then after everything over okay, playing each one get two dollar. We got many currency…through the fun fair they give us fun fair we buy things use the xxx <name of the nursing home> currency. Then the money whatever we want from whatever we have, they let us buy.” (E4, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

Many residents spend a significant amount of time sleeping or watching television. Those who are fluent in English and Mandarin have limited access to newspapers in these two languages. Residents who can read Malay or Tamil do not have access to newspapers in those languages. Two Nursing Home D residents expressed their regret that the nursing home no longer provided them with English and Mandarin newspapers. One resident whose length of stay is within 3-5year timeframe in the nursing home spoke about not having his reading glasses with him as he left it in his home. Two residents shared that they are unable to read or watch TV due to poor eyesight.

For most of the residents, except for Nursing Homes D and E, the first author observed that staff bring them, including several bedbound residents in geriatric chairs, to the common dining hall for lunch and dinner. Most of the residents at Nursing Home D receive their meals at their bedside/in bed. Nursing Home E has a cluster-style family unit concept, with each family unit having a living room. Each family unit has about ten residents, and they are encouraged to eat together as a family in the living room. There are group exercises or occupational therapy activities in small groups following the COVID-19 restrictions on the number of people in group activities.

Sense of belonging

Residents who feel connected to the nursing home and volunteer their services are meaningfully occupied and experience Joy in Living. 4 out of 25 participants, or less than 20%, reported volunteering their services in the nursing home. During two observation sessions at Nursing Home C, six male residents were observed assisting with nursing home tasks such as folding washed laundry, towels, and unused trash bags. During an observation session at Nursing Home B, a staff member mentioned a female resident who assists them with tasks such as drying medicine cups and encouraging fellow residents to take their medication. A male resident was observed folding washed laundry and towels during a post-interview observation session at Nursing Home E.

“I can pour water for the plants.,. So, if you have a sincere heart, pour water for the plant…Because I came into this place; and I thank God.” (C5, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

A male Chinese resident sitting nearby is busy folding plastic trash bags. He is the only one doing this.

Observer:

“Why are you folding the trash bags?”

Resident:

“I like to do. I like work, not boring.” (Impromptu Conversation during (2nd Observation at Nursing Home C)

“Then I see so boring ‘ah’ if sitting down. Last time, cooking washing, sweeping all everything do, come here nothing to do, sit down 'makan' <eat food> only. Then I say, “auntie I help you”. She say, she say “your wish, can, can” …. I fold plastic, then cloth, our ‘makan’ cloth, towel all wash and come, then the next room auntie also fold the towels… Here got the cloth folding all I like.” (E2, Length of Stay: 1 to 2 years, Female, Indian)

Pursue interest

Meaningful daily activities organised by nursing homes, combined with time to pursue personal interests, contribute to the elderly residents’ Joy in Living experiences.

“Then the rest of the time I read, I got a lot of books there, and I play ‘Sudoku’ <number game>. You will be surprised.” (A5, Length of Stay: >years, Male, Chinese)

“Because I came into this place, I study more and more <the bible>, I pray every day…cos now I stay in this home even if I don’t go out is a heaven to me.” (C5, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

Avoid boredom

Loneliness and boredom can result from a lack of meaningful social and recreational activities. Five residents, or 20% of the participants, reported feeling bored because of a lack of evening and weekend activities.

“Down here, cannot, nothing. By 5 o’clock I call it a day. I just lie down.” (A2, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“Yeah, one thing got no night activity like karaoke room. All these very bored ‘lah’ stay here. Everyday don't know what to do. Luckily, I got my own phone. I can see the ‘YouTube’. At nighttime, if you cannot sleep I tell you, you don't know what to do. Every night, middle of the night wake up at least three times. Wake up, why haven't morning yet? Lie down I thought what three, four hours of sleep, wake up ‘wah’ <Singlish expression to profess surprise or shock, like the expression ‘Oh my God!’> one hour only. The more you think about it, you cannot sleep at all.” (A3, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“Now, down here, there is not much activity. And then we are sort of restricted living here… My closest thing is a newspaper and the television… Plan all these activities that I can participate, I find that it’s very interesting. Because I don’t like to be bored you see. Anything that I can do I like to do. I’m not particular.” (C3. Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“Sleeping ‘lah’ <In the afternoon>. Before, yes, but now because of all these uh, censorship of everything <Covid restrictions>. They don’t do anything else <referring to activities like painting, art and craft etc.>.” (D2, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Chinese)

“We watch TV. Very very very tired. Nothing to do.” (D3, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Female, Chinese)

“Nothing. I lie in the bed, daydreaming <in the afternoon>.” (D4, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

There are activities planned in Mandarin for the Chinese ethnic majority residents. During a weekday afternoon observation session, I observed a 1.5-hour online ‘Zoom’ singing session in Mandarin organised by church volunteers at Nursing Home A. When I asked an ethnic minority resident from Nursing Home A if there were such online volunteer activities regularly, she replied,

“Tamil don’t have.” (A1, Length of Stay: 3–5 years, Female, Indian)

D1 and E2, both members of an ethnic minority community, reported that having a personal tablet issued upon admission and access to more TV sets in the family units' living rooms, respectively, allows them to watch TV programmes of interest and in their vernacular language. Loneliness is exacerbated by the limited interactions between residents and their family members, friends, and volunteers because of COVID-19 safety measures that restrict and, at times, prohibit visits or outings for extended periods when COVID-19 community cases increase.

“That time was a group of Christians. They come Sunday then they will pray for you, they sing song, worshipping. Then a lot of activities cancelled because of Covid.” (A3, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“<Resident’s wish for volunteer visits to resume> Make me happy. Not lonely.” (C1, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

“Now cannot go out much. First time when I first come here, we one week will all go walk the gardens. Outside go somewhere the gardens. Sometime go eat outside.” (E3, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

Three residents reported that their lives in the nursing home were less lonely than their lives in the community. Because of his debilitating illness, one resident was cut off from external social networks before moving to the nursing home. Because of their limited mobility, the other two residents were confined to their homes. There are a few staff members with whom they can converse at the nursing home.

“I got more people to talk to… More of the staff… They have interesting hobbies and interests that I can talk to them.” (B4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“I like ‘ah’ <Singlish expression to express something is already known in a sentence>, to meet many people, have many friends. Talking to each other like friends. Friends with the residents and staff. At home, I am very dull, just my sister. I don’t have friends at home.” (D4, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

Connectedness through meaningful relationships

Several studies on the well-being of seniors have emphasised the importance of developing new relationships as well as maintaining prior personal relationships to be socially included [12,17-19,38].

Results Of Theme 3 - Connectedness Through Meaningful Relationships

All twenty-five participants emphasised the value of establishing new relationships with caregivers and other residents, as well as maintaining existing ones with family and friends to enhance their experiences of Joy in Living.

Develop new relationships

Language barriers are one obstacle to forging new relationships with foreign caregivers.

“Here, you get to meet with them often and get to know them closely... But generally, it probably is a lot of them is from other countries like Myanmar that they can’t talk and understand English well <referring to foreign staff>.” (B4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“Another reason which I'm pretty quite reluctant to tell you is that some of the staff they're not very well versed in talking to me in English... Foreigners like Myanmar... Even, even the Indian staff. When they speak English, it’s a bit different from our Singaporean English.” (D1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

One resident talked about how she finds it difficult to build new relationships with caregivers and other residents because she fears being misunderstood and being the target of gossip.

“Because sometimes you talk the words can become, cause problems with other resident, even staff, I don’t talk so much.” (B1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

Another resident expressed his mistaken belief that staff members shouldn't engage in conversation with residents. This may have been influenced in part by his time spent behind bars in drug treatment facilities from his adulthood to middle age.

“Actually staff, they are not supposed to chit chat with us all. Cos this is a government place.” (C5, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

11 out of 25 participants, or over 40% of the participants, mentioned additional difficulties in building relationships with care staff, including staff displeasure at having to perform tasks like cleaning soiled diapers of elderly residents and/or staff fatigue from having to look after all residents.

“Their temperament is bad. Because other things, certain things you cannot complain. You ‘pangsai’ <pass motion> they want to wash you up, is very good. I think most of them are annoyed because of the washing up, they have to wash our backside or shower us, and they’re not happy with that... They talk among themselves and show their face.” (B3, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Chinese)

“I don’t want to trouble them, all busy. All okay ‘lah’ here. I just watch TV ‘lah’. They put me to sit facing the TV with Chinese shows. Chinese TV also watch.” (C6, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Malay)

“Not convenient for them if you ask them, they are busy.” (D4, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

“Oh, here got 60 over <residents>. I think so, I not very sure. So many people cannot do any much. I my own also not clever.” (E3, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

A little less than half of the participants-12 out of 25-reported having friendships with care personnel.

“Actually, the staff are quite good. I mean quite good to the residents. They don’t shout around or bully them. They are very gentle to them and always attend to their requests. …Yeah, we get along quite well. I trust them. Nothing very personal.... Just the daily needs and all that. One or two only that are willing to buy for me. Close to me.” (C3, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“All the nurse(s) are very good... Sometime I talk phone to my daughter, my family. I never talk about family story with the nurse, but they know because they know my daughter come here, children come here.” (E2, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Female, Indian)

In all five nursing homes, the first author noticed that most staff members were more concerned with getting things done quickly and making sure residents were safe than getting to know them. Several foreign employees in all five nursing homes were shown to be able to communicate with the residents in a few words in Mandarin and Malay. However, this was mostly done to give them orders rather than have a conversation with them.

While the staff is courteous and patient, there is no interaction beyond the task of feeding them safely without choking…The interaction is mechanical. Although the staff uses a few words of Malay, it is mainly to ask what colours the resident wants from the colour pencil set. (2nd Observation at Nursing Home A)

On the other hand, mid-career local hires who assist with non-nursing care and organise social and recreational events can interact and have dialogues with residents in vernacular languages, as explained in section 5.2 on ‘Person-centred Care’.

The situation is worse when it comes to making acquaintances with other residents. Only ten out of the 25 participants, or 40%, claimed to have friends among the inhabitants. Most of the residents face challenges with forging friendships with others, including those from other ethnic communities and the dominant Chinese ethnic population who speak Mandarin and other dialects, include both sexes and have a variety of educational backgrounds.

There are difficulties, including language problems and being on a separate wavelength to others while making acquaintances with people, especially for residents from ethnic minority groups.

“…the residents. They are Chinese educated. The TV is in Mandarin the whole time. Day and night, they want Chinese... So, I hardly have anybody to talk to. I only talk to one…, I’m the bystander, I don’t care. I don’t care but I don’t like it. I mean it’s wrong to scold somebody, somebody’s mother or things like that. What has somebody's mother done to you? People's mother already die. What are you gonna do? But these are the kind of things that these Chinese educated are saying. Truly the nursing home should have educated people, not like all these Chinese educated ‘Jepalang’ <motley crew> cases” (A2, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“I don't talk to residents here. There's nobody here that I can really talk to. Because the things that I like to talk about would not be things that they would understand or be interested in. We don’t share common interests. Okay, but if you ask them to talk then they use vulgar language at all. I'm not used to using that kind of language.” (A5, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

“Not like close friends, just say hi… Matter of interest <different interests>. I like to do things that will help me to improve.” (B4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“Friend, but they never talk. All Chinese. I don’t know Chinese. I speak Malay, English. I Eurasian.” (B5, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Eurasian)

“Ah, wow. None of them. No friends. No friends…. Most of them are Mandarin speakers. For example, the one man in front of me and beside me. They're all Mandarin speakers. They can speak one or two, maybe 10 or 20 words, but there's no possibility of communicating.” (D1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

“Yeah, we talk but normally I not very close much. Because I know which, which people are the same. I don’t like in my heart thing to talk to people… Oh yeah, yeah. Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Mandarin, Malay. That’s all. I can talk, maybe deep thing I don't know, maybe ‘ah’… Yes, yes, not much the inside thing...”. (E3, Length of Stay: 3 - 5 years, Female, Chinese)

A member of an ethnic minority community claimed to have experienced racial prejudice.

“I like to join them, but sometimes their character is not good, I don’t want to join. Resident ‘ah’ some resident here very rude, very you know the ‘color-mind’. The skin. Yeah, the old timers here like that old already, the young ‘ah’ now no nothing <referring to the younger generation>. The old ‘ah’ last time people like that <referring to the older generation>, see ‘color’ one. They don’t want to talk; they talk to each other, you know? Then we just sit down like stone. Better we stay in bed 'ah', I don't want to join.” (E1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)

Ethnic minority participants who live with other residents who can speak their native tongue are among those who said they had friends in the nursing home.

“Everybody talk to me. One, if he got some extra food, he will always give to me. He give me biscuit. He cannot see well. He is a Malay.” (C6, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Malay).

“Like me one auntie, like my sister ‘lah’. My friend. She stroke or what, cannot walk. My room only. One year after me only then she come. She got three children, no husband. Husband pass away already. We all talk family story. Talk about me, talk about her <she is Indian, and they speak in Tamil>.” (E2, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Female, Indian)

Maintain familial and prior relationships

According to the Continuity Theory [39], sensations of Joy in Living can grow when there are opportunities to sustain current relationships for the continuity of prior roles.

“My birthday. My lawyer <friend> will come. Every year he will buy a big cake for me and for the residents... Good friend in the case that I have my friends who bring me stuff. I give them a call.” (A4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

“My two sons here, I would say they’re very good. This is why I’m blessed. I think among all the residents here, I’m the luckiest… I got a lot of things to talk to them. You know I see a lot of them when the children come, just leave the food and not spend time talking to them. “Okay Pa, then they go out.” So, it’s a very short visit. They just come with some food and all that. The impression I get is as if they come because they are obligated to. My son can sit here for hours… Because there’s so many things, I can talk with them.” (A5, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

On the other hand, the residents experienced a great deal of anxiety and grief because of the absence of possibilities to address concerns relating to family members’ unilateral decision to place them in a nursing home, bequest, and/or reconcile damaged relationships.

“I want to go outside to eat. I feel homesick. I hope my brother will discharge me. I asked him. He said no. No one to look after you unless you can start walking.” (D4, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

“Morning, morning I cry already. My house. The last one boy, he say, “I want my father house”, he say… My number 1 daughter, her husband say the house sell and then CPF take the money, they give you. You stay in home here… I mean, the boy he don’t like. He want house. I give house to him. I sell already, the boy where go? I stay ‘sini’ <here in Malay>, where the boy go, where?” (A1, Length of stay: 3-5 years)

“That is what people say. What people do is different. Well, I don’t know why they think this way. I always look after the family. I’ve never been disloyal. When I go back to my home in Melbourne, I’m afraid I don’t know how to say why are you this way. I’ve done nothing wrong. You’ve done wrong with me… My family never contact me.” (A4, Length of Stay: 1-2 years, Male, Chinese)

More than half of the participants-13 out of 25 residents-reported having troubled family relationships. Proxies for poor relationships include few or nonexistent calls or visits from family members, venting about being put in a nursing home by their family, bequest disputes, and abandoned or estranged family relationships. The other individuals enjoy supportive or positive relationships with their families. During an observation session, a senior member of the nursing staff casually mentioned that many of the home's residents didn't have a lot of family support.

“I think that family support also plays a big role, but unfortunately here, family is not so supportive. Very few percentage have family support.” (Impromptu Conversation with Assistant Nurse Manager 1 at Post-interview Observation at Nursing Home E)

Fulfil the need for spiritual care

Three Freethinkers (those who accept the concept of a superior being like God or deities but form opinions and think independently of any religious dogmas), one Atheist, and participants who belong to the major religious traditions of Singapore's population (Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, Islam and Hinduism) are represented in this theme. Despite the variety of religious and spiritual convictions, two common sub-themes emerged: (i) the use of one's religious or spiritual beliefs as a compass while facing life’s difficulties; and (ii) the provision of support for individual spiritual needs. A life of purpose and guiding values emerged as two other sub-themes. The intra-connection a person has with themselves in terms of values, meaning, and purpose in life, as well as the relationship with God or the cosmos, are two of the four domains of the Spiritual Well-being Model [40,41]. The Environmental Domain of the Spiritual Well-being Model emphasises connection and harmony with nature, having a deep sense of calm and being in awe of its beauty when spending time in nature (strolls in the park, forest treks, etc), and the Communal Domain emphasises one's relationships with others (covered in theme 3). New information regarding the necessity of assisting the elderly in seeking forgiveness, reconciliation, and letting go of the weight of regret surfaced during the coding and analysis of the data from the last two nursing homes. In Erik Erikson’s eighth stage of human development, ‘Integrity vs Despair’, the urge to forgive oneself and work toward reconciliation is a crucial final psychological stage that takes place in old age [16]. Support for forgiveness and reconciliation is the new fifth sub-theme.

Results of theme 4 - Fulfil the need for spiritual care

Religious or spiritual beliefs

There are both good and bad religious coping mechanisms [42]. When someone practices positive religious coping, they experience a strong spiritual connection with their family, friends, and the larger community and are generous in giving and kind to others. A little over 70% of the participants, or 18 out of 25 participants, reported adopting positive religious coping mechanisms to varying extent, which were evident in their positive attitudes toward their lives and a feeling of meaning and purpose in their daily activities.

“I pray every day in the room. My heart I pray, chant. I pray in the morning, before breakfast. I don’t have a wicked heart. I don’t hurt people. I think nothing wrong. If you do something evil maybe you scared…I believe that if there is no God, we cannot come to this world. There is a God then you come to this world… Whatever the world is given we take. You make good karma, so you can get good things. Good karma is a blessing… I believe that whatever I want, God give me, that one I believe.” (B1, Length of Stay; 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

“I cannot kneel on floor. I sit in the wheelchair and always praying in my heart, always praying in my heart the Quran. Anytime I pray… Give me joy pray Allah… Pray Allah really make me healthy. Bless family with health and money.” (C6, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Malay)

“I pray to God my leg don’t cramp too often. I ask God to give me strength to bear the pain. The only problem give me is my leg now. Last time my leg seldom cramp. Now everyday cramp.” (D4, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Chinese)

“In fact, at all times. Sometimes when I shower, I was eating, I was doing my things whatever thing, I have been like in prayer mood, deep in tune with God… I believe that after I die, I will go be with the Lord, go to be with Jesus, Jesus will bring me to heaven.” (E4, Length of Stay: >5 years, Male, Chinese)

Nine individuals, or just over one-third of the group, keep mementos of their religion or a copy of their holy book nearby and pray before going to sleep.

“Got the photo God, I put on top small cabinet near my bed and I pray. All God photo, ‘Vinayagar’, ‘Lord Shiva’ <Hindu deities>, got ‘ah’, pray. I Hindu must pray in the morning after bathing... Before I sleep, I pray.” (A1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Female, Indian)

The remaining residents who practice a religion said prayers from memory because they forgot to bring their holy books to the nursing home.

“In my heart. What I can remember, I just read from my heart.” (C6, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Malay)

“Nobody, nobody knows that I bookless <prayer book>. I wanted to call my nephew to bring for me, he always says he got no time.” (D3, Length of Stay – 1- 2 years, Female, Chinese)

Two Hindu individuals who do not maintain religious symbols by their bedsides either decided not to or misplaced the picture.

“… can keep but I don’t want, don’t know why... I don’t want, I never ask before. I don’t like, don’t know why.” (E1, Length of Stay: 3-5 years, Male, Indian)