When to Avoid Dialysis during Protein Purification?

*Corresponding Author(s):

Marathe GKDepartment Of Studies In Biochemistry, University Of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysuru, 570006, Karnataka, India

Tel:+91 9686423624,

Email:marathe1962@gmail.com

Abstract

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

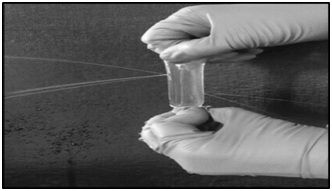

Proteases derived from lower organisms have enormous industrial applications and researchers are on a quest for newer sources of proteases with high catalytic turnover and stability. In the process of searching for an industrially useful acid protease, we came across a strain of Aspergillus niger that produces thermostable acid protease. We initially enriched this enzyme using ammonium sulphate salting out method. The protease was salted out with 50% ammonium sulphate. To remove ammonium sulphate for the next step, we employed dialysis tubing with a molecular weight cut off 10KDa. We found dialysis tubing undergoing multiple, irregular perforations in the membrane, resulting in loss of the sample. We initially suspected a manufacturer’s defect in dialysis tubing, but that was not the case. Upon careful analysis, we found that perforation was due to co-eluting cellulase(s) acting on dialysis tubing. We then successfully employed biogel-P100 (gel filtration matrix made out of polyacrylamide beads) to remove ammonium sulphate. We believe that these findings offer a precautionary message both to students and researchers alike while dealing with fungal enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Methods

Assay of acid protease: Acid protease was assayed as described by [4] with slight modifications. Briefly, 2% haemoglobin (acid denatured) prepared in 0.1 M acetate buffer pH 4.0 was used as substrate. To this, 0.4 mL (0.5-5µg) enzyme was added and incubated at 60°C for 10 min. The reaction was arrested by the addition of 2 mL of 5% TCA and the tubes were incubated at room temperature for 20 min. After 20 min, the reaction mixture was filtered through Whatman filter paper no.1 and the absorbance of the supernatant containing released tyrosine was measured at 280 nm. The amount of tyrosine released was calculated using a tyrosine standard (0-60 µg/mL). One unit of protease activity is defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1µg of tyrosine per minute, under standard assay conditions.

Assay of cellulase: Cellulase assay was carried out as described by Wood and Bhat [12] with slight modifications. In brief, 0.1 mL (50-150µg) enzyme was added to 0.9 mL of 1% CM-cellulose prepared in 0.1 M acetate buffer pH 5.0. The enzyme reaction was carried out at 40°C for 120 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 mL of DNS reagent. The tubes were boiled in boiling water bath for 10 min, cooled and added with 8 mL of distilled water. The absorbance was read at 540 nm and the amount of glucose released was calculated using a glucose standard (0-1000 µg/mL). One unit of cellulase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that liberates 1µmol of reducing sugar (expressed as glucose) per minute, under standard assay conditions.

Ammonium sulphate fractionation of acid protease: To the culture supernatant, ammonium sulphate was added to 30% saturation and then subsequently to 50% and 60%, with constant stirring at 4°C for 6 h. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 7000 g for 30 min at 4°C (in some experiments an aliquot from each fractionation was kept aside for assays of protease and cellulase).

Dialysis: 50% ammonium sulphate pellet showing the highest specific activity was re-suspended in 50 mM acetate buffer pH 5.0 containing 0.1 M NaCl and dialyzed against same buffer.

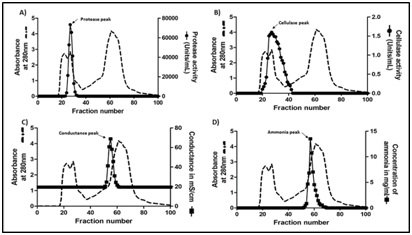

Biogel-P100 chromatography: 50% ammonium sulphate pellet showing the highest specific activity for protease was resuspended in 50 mM acetate buffer pH 5.0 containing 0.1 M NaCl. This sample (2ml containing 100mg protein) was loaded on to a 1.5cm × 78cm column packed with 137ml of Biogel P100 polyacrylamide beads, equilibrated with 50 mM acetate buffer pH 5.0 containing 0.1 M NaCl and eluted with the same buffer. Fractions were collected at a flow rate of 20ml/h and monitored for absorbance at 280nm. Each fraction was assessed for the presence of protease, cellulase and ammonia (see below).

Protein estimation: Protein estimation was carried out as described by [13] and Biuret’s method [14]. A) Lowry’s method: This method involves two reactions leading to color complex formation. In first reaction copper [II] reacts with the peptide bond in the protein under alkaline conditions, resulting in their reduction to cuprous [I] ions. The subsequent reaction involves the reduction of phosphomolybdicphosphotungstic acid to heteropolymolybdenum blue by the copper-catalyzed oxidation of aromatic acids. The blue complex formed is measured at 660 nm. The concentration of protein present in the sample is calculated using standard graph constructed with BSA as standard (15- 75 µg/mL). B) Biuret method: Under alkaline condition copper [II] ions reacts with peptide bond and forms mauve-colored coordination complex, which is measured at 540 nm. Amount of protein present is calculated using standard graph constructed with BSA (1-5 mg/mL).

Quantification of ammonia: Ammonia quantification was done using Nessler’s reagent [15]. Each fraction from Biogel P-100 was treated with Nessler’s reagent and absorbance was read at 425 nm. The amount of ammonia was calculated using a standard (1-20µg/ml) made with ammonia solution.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The global sales of industrial enzymes account for more than 3 billion USD of which proteases constitute more than 60% [16]. These proteases have wide range of applications and are mostly derived from microbial sources [17]. Among the microbes, enzymes derived from filamentous fungi such as Aspergillusspecies have many advantages over the other microbial sources, due to low cost of production, amenable for easy downstream processing, coupled with faster growth of the fungi and secretory nature of the enzyme [18]. While screening for an industrially useful protease from Aspergillus species, we came across an acid protease from Aspergillus niger which had industrially desirable qualities such as high catalytic turnover and thermostability. Hence, we decided to purify this fungal protease by conventional protein purification techniques. Precipitating the proteins by ammonium sulphate (salting out method) is a routine and simple technique widely used during protein purification. However, subsequent removal of residual ammonium sulphate is very much essential for further purification of the enzyme. In an effort to separate ammonium sulphate from the sample, dialysis was carried out using nitrocellulose membrane. But, every time during dialysis the sample was lost, as a result of formation of pores in the membrane (Figure 1). Although we suspected manufacture’s defect initially, later we found an enzyme culprit responsible for this act. This culprit was cellulase. Accordingly, we found detectable cellulase activity in all the fractions that were also positive for proteases (Table 1). In order to separate ammonium sulphate we used spin columns (made of polyethersulfone) but this resulted in low recovery of the enzyme. Hence, we proceeded with differential ammonium sulphate fractionation, in an attempt to separate cellulase from protease. However, cellulase activity was also enriched with protease activity in all the steps of differential ammonium sulphate fractionation (Table 1). Therefore, we decided to use other chromatographic separation steps, which require prior removal of ammonium sulphate. Among the available methods, simple dialysis was the method of choice. However, we came across the problem of cellulase action on dialysis tubing. Therefore, dialysis is not always the best technique for the removal of small molecules. Cellulases degrading cellulose is not new [19], but while purifying proteases co-purifying cellulases degrading cellulose was new to us. Similar difficulty was also encountered recently by Monico et al., where dialysis was not efficient in removing EDTA [20]. Other option for us at this stage was to use non-cellulosic dialysis membrane, but then they are expensive and often available in broad cut off range and not available with all the vendors. Hence, we decided to use biogel-P100.

Biogel-P-100 effectively removes ammonium sulphate

|

Sample |

Volume mL |

Protein mg/ml |

Protease |

Cellulase |

|||

|

Activity U/mL |

Specific activity U/mg |

Activity U/mL |

Specific activity U/mg |

||||

|

Crude extract |

47 |

15.4 |

3835.8 |

249 |

2.64 |

0.171 |

|

|

Ammonium sulphate 30% supernatant |

50 |

13 |

4319.9 |

332.2 |

1.49 |

0.114 |

|

|

Ammonium sulphate 30% pellet |

4 |

50 |

4748.5 |

94.96 |

11.35 |

0.227 |

|

|

Ammonium sulphate 50% supernatant |

49 |

8 |

95.2 |

11.9 |

- |

- |

|

|

Ammonium sulphate 50% pellet |

4 |

53.8 |

37281.1 |

703.4 |

16.9 |

0.314 |

|

|

Ammonium sulphate 60% supernatant |

46.5 |

6 |

12.87 |

6.4 |

- |

- |

|

|

Ammonium sulphate 60% pellet |

0.8 |

16 |

5003.7 |

312.6 |

0.78 |

0.048 |

|

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

REFERENCES

- Graslund S, Nordlund P, Weigelt J, Hallberg BM, Bray J, et al., (2008) Protein production and purification. Nat methods 5: 135-146.

- Siala R, Sellami-kamoun A, Hajji M, Abid I, Gharsallah N, et al., (2009) Extracellular acid protease from Aspergillus niger I1: purification and characterization. Afr J Biotechnol 8: 4582-4589.

- Ire FS, Okolo BN, Moneke AA (2011) Purification and characterisation of an acid protease from Aspergillus carbonarius. Afr J Food Sci 5: 695-709.

- Vishwanatha KS, Appu Rao AG, Singh SA (2009) Characterisation of acid protease expressed from Aspergillus oryzae MTCC 5341. Food Chem 14: 402-407.

- Zanphorlin LM, Cabral H, Arantes E, Assis D, Juliano L, et al., (2011) Purification and characterization of a new alkaline serine protease from the thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora sp. Process biochem 46: 2137-2143.

- Arakawa T, Timasheff SN (1984) Mechanism of protein salting in and salting out by divalent cation salts: Balance between hydration and salt binding. Biochemistry 23: 5912-5923.

- Grodzki AC, Berenstein E (2010) Immunocytochemical methods and protocols-Antibody purification: Ammonium sulfate fractionation or gel filtration. Methods mol biol 588: 15-26.

- Stanley PG (1963) Interference of ammonium sulfate with the estimation of protein by biuret reaction. Nature 197: 1108.

- Niamke S, Kouame LP, Kouadio JP, Koffi D, Faulet BM, et al., (2005) Effect of some chemicals on the accuracy of protein estimation by the lowry method. Biokemistri 17: 73-81.

- Lee SY, Khoiroh L, Ling TC, Show PL (2015) Aqueous two-phase flotation for the recovery of biomolecules. Sep purif rev 45: 81-92.

- Sankaran R, Manickam S, Yap YJ, Ling TC, Chang JS, et al., (2018) Extraction of proteins from microalgae using integrated method of sugaring-out assisted Liquid Biphasic Flotation (LBF) and ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem 48: 231-239.

- Wood TM, Bhat TM (1998) Method for Measuring Cellulase Activities. In: Cellulose and Hemicellulose, Methods enzymol, New York academic press, USA, pg. no: 87-112.

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265-275.

- Gornall AG, Bardawill CJ, David MM (1949) Determination of serum proteins by means of the biuret reaction. J biol chem 177: 751-766.

- Bock JC (1941) Determination of urea nitrogen. J Biol Chem 140: 519-523.

- Sumantha A, Larroche C, Pandey A (2006) Microbiology and Industrial Biotechnology of Food-Grade Proteases: A Perspective. Food Technol Biotechnol 44: 211-220.

- De Souza PM, De Assis Bittencourt ML, Caprara CC, De Freitas M, De Almeida RPC, et al., (2015) A biotechnology perspective of fungal proteases. Braz J microbiol 46: 337-346.

- Rao MB, Tanksale AM, Ghatge MS, Deshpande VV (1998) Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiol mol biol rev 62: 597-635.

- Hurst PL, Nielsen J, Sullivan PA, Shepherd MG (1977) Purification and properties of a cellulase from Aspergillus niger. Biochem J 165: 33-41.

- Monico A, Martinez Senra E, Canada FJ, Zorilla S, Perez Sala D (2017) Drawbacks of dialysis procedures for removal of EDTA. PLoS One 12: 1-9.

Citation: Purushothaman K, Bhat SK, Siddappa S, Rao AGA, Kadappu KB et al., (2019) When to Avoid Dialysis during Protein Purification? Adv Ind Biotechnol 2: 009.

Copyright: © 2019 Purushothaman Kavya, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.