Work-Related Burden on Physicians and Nurses Working in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A Survey

*Corresponding Author(s):

Fauchère JCDivision Of Neonatology, Perinatal Centre, University Hospital Zurich, University Of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Tel:+41 442553584,

Fax:+41 442554442

Email:jean-claude.fauchere@usz.ch

Abstract

Methods: Transversal descriptive study using an anonymous questionnaire.

Results: Fifty-two neonatal physicians and 60 nurses took part in this survey (response rate 77%). Altogether, 78% stated that the difficult medical and ethical dilemmas represent a burden to them. 87% experienced this work burden as momentary, and 12% as long-lasting. In 40% of the respondents, their private life was affected. Exhaustion was the most frequently cited stress symptom (physicians 25%, nurses 15%). Close to 90% of the caregivers were offered a platform for team debriefings and discussions or pastoral assistance by their hospital, but most of the respondents found relief from stress through discussions with family members and friends (20%), and through their hobbies (15%), or both (43%).

Conclusion: Working in a NICU environment represents a burden for the majority of neonatal health care providers. Exhaustion was the most frequent symptom. Social contacts with family and friends and hobbies are the coping strategies found most helpful. Staff meetings, debriefing platforms and pastoral assistance help alleviate work-related stress.

Keywords

ABBREVIATIONS

ICU: Intensive Care Unit

NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

INTRODUCTION

Tremendous changes have taken place within neonatal intensive care units over the last two decades with higher patient acuity and increased parental expectations regarding the ability to save very sick or extremely premature infants. This has led to a substantial increase in work load and staff stress. Despite this, little information has been collected about the impact of work-related burden on neonatal caregivers. Most available studies pertain to health care providers working in adult ICUs [13-16] or in pediatric ICUs [17]. They all report high burnout levels affecting up to 50% of ICU physicians and nurses, and they show that the high level of work-related stress encountered by HCPs in an intensive care environment has the potential to significantly impact on the caregivers’ perceptions about the value of their work, feelings of success, performance and welfare. Braithwaite and Oehler showed that stress and burnout among pediatric nurses represent a concerning issue [18,19]. Important stress and burnout in HCPs have been shown to have strong effects on quality of patient care [16,20-23]. In a recent survey to measure burnout in a cohort of Italian neonatal physicians, Bellieni and co-workers called attention to the alarming situation. They found a very high burnout incidence with 60-65% of neonatologists being in the ‘at risk’ burnout range, and another 30% experiencing high burnout [20]. A large cross-sectional survey study on burnout in the NICU setting by Profit et al., involved 2073 nurses, nurse-practitioners, respiratory care providers and neonatal physicians working in 44 NICUs. The burnout rate of the staff varied significantly between NICUs, ranging from 7.5% to 54.4% and was less prevalent in physicians compared with non-physicians [21].

We hypothesized that neonatologists and nurses working in tertiary NICUs experience a high and enduring work-related burden which affects not only their own health but also impacts on their private life. Our survey therefore aimed at exploring the type, degree and duration of work-related burden on neonatal physicians and nurses working in Swiss level III neonatal intensive care units, its impact on their private life, and to assess which strategies are found helpful by the caregivers to cope with the work-related load.

METHODS

For this survey, we added 6 questions on work-related burden (Table 1) as a separate section to a larger questionnaire on ethical issues in neonatal intensive care and on caregivers’ practices. The questions concerned the following domains: 1) physical and psychosomatic symptoms; 2) the frequency of occurrence; 3) the duration of burden; 4) the influence on private life caused by work-related burden; 5) individual coping strategies; and 6) the availability of institutional support and debriefing opportunities.

| Q1. Over the last 6 months, did you suffer from: | 1. Physical complaints |

| 2. Psychosomatic symptoms (such as sleep disturbance, eating disturbance, etc.) | |

| 3. Exhaustion | |

| 4. None | |

| Q2. Do ethical dilemmas and difficult decisions taken in the NICU represent a burden to you?1. Yes often | 1. Yes often |

| 2. Yes sometimes | |

| 3. Rarely | |

| 4. Never | |

| Q3. How long does this burden last? | 1. Momentary |

| 2. Long-lasting | |

| 3. Chronic | |

| Q4. Does this work-related burden affect your private life? | 1. Yes often |

| 2. Yes sometimes | |

| 3. Rarely | |

| 4. Never | |

| Q5. How do you cope with this burden? | 1. My hobbies (music, sports, yoga etc.) |

| (several answers can be given) | 2. Discussion with family members and friends |

| 3. Religion | |

| 4. Personal therapist | |

| Q6. Are there one or several support and debriefing opportunities available in your institution? | 1. Routine debriefings after difficult decision making processes are available |

| (several answers can be given) | 2. Routine team debriefings under the moderation of specially trained moderators |

| 3. I have the possibility to hold team discussions without the help of a trained moderator | |

| 4. The assistance to the neonatal team from the hospital’s pastoral care is available | |

| 5. No routinely implemented institutional assistance to relief the work-related burden is available |

The questionnaire was in German language and also consisted of general demographic information about the respondent. The questionnaires were sent to the medical NICU directors and to the head nurses to be distributed among all physicians (residents, fellows and attending physicians) and nurses on clinical duty that day. For this cross-sectional pilot study, we aimed at enrolling a minimum of 100 participants (out of 400 HCPs for the nine NICUs, 25%), and at least eight physicians and eight nurses per center. After duly completion and using a prepaid envelope, the questionnaires were returned anonymously by each respondent to the study investigators. No second call was sent out. Ethical approval for this type of self-administered, anonymous questionnaire survey of health care providers was granted by the Ethical Commission of the Canton Zurich.

The answers were then analyzed using Excel (Mac version 2008 and Windows Office 2010) and Matlab (Matlab version R2010a for Mac OS X, Mathworks), and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22). We present here the data on the work-related burden on neonatal HCPs working in a tertiary neonatal intensive care setting as absolute frequencies, and as percentages with the 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). Answers of various groups (men vs women, physicians’ vs nurses) were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests for ordinal variables, and Chi-square tests for categorical variables.

RESULTS

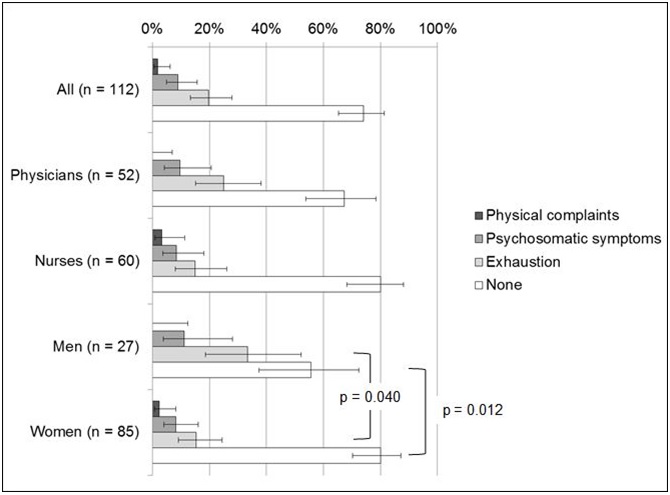

83 (74.1%; 95% CI 65.3-81.3%) of all participants did not suffer from physical complaints, psychosomatic symptoms or exhaustion (Table 1, Q1). A higher percentage of women than men said they suffered from none of these complaints (p=0.012). Physical complaints were experienced only by 2 participants (1.8%; 95% CI 0.5-6.3%), psychosomatic symptoms by 10 participants (8.9%; 95% CI 4.9-15.7%), and exhaustion by 22 (19.6%; 95% CI 13.3-28.0%). Men suffered more frequently from exhaustion than women (p=0.040). No significant differences were found between physicians and nurses. The distribution of the answers among neonatal physicians and nurses is shown in Figure 1.

When asked ‘if ethical dilemmas and difficult decisions taken in their NICU represent a burden’ to them (Table 1, Q2), 17 (15.2%; 95% CI 9.7-23.0%) of all HCPs experienced this burden as frequent, 70 (62.5%; 95% CI 53.3-70.9%) as occasional, and 22 (19.6%; 95%CI 13.3-28.0%) as rare. Three participants (2.7%; 95%CI 0.9-7.6%) stated that this did not represent a burden. The answers were similarly distributed among physicians (3.8%; 11.5%; 69.2%; 15.4%), and nurses (1.7%; 18.3%; 56.7%; 23.3%) respectively. No significant differences were found between physicians and nurses, or between men and women.

To the question on ‘how long this burden lasts’ (Table 1, Q3), the duration was described as momentary by 83 (87.4%; 95% CI 79.2-92.6%) participants, as long-lasting by 11 (11.6%; 95% CI 6.6-19.6%), and as chronic by one HCP (1.1%; 95% CI 0.2-5.7%). This overall distribution hold true both for the physicians (88.6%; 11.4%; 0%) and for neonatal nurses (86.3%; 11.8%; 2.0%). No significant differences could be found between answers given by physicians and nurses, or by men and women.

Regarding the question as to whether this work-related burden affects their private life (Table 1; Q4), 4 HCPs (3.6%; 95% CI 1.4-9.0%) experienced this as being often the case, 40 (36.4%; 95% CI 28.0-45.7%) as occasional, 53 (48.2%; 95% CI 39.1-57.4%) as rarely, and 13 participants (11.8%; 95% CI 7.0-19.2%) answered that this was never the case. Figure 2, depicts the distribution of the answers among neonatologists and neonatal nurses. Again, there was no significant difference between physicians and nurses, or between men and women.

When asked about how they cope with this burden (Table 1, Q5, several answers could be given) the following coping strategies were named. Forty-eight participants (42.9%; 95% CI 34.1-52.1%) indicated hobbies and discussions with family members and friends; eight HCPs (7.1%; 95% CI 3.7-13.5%) named hobbies, discussions with family members and friends, and religion; seven (6.3%; 95% CI 3.1-12.3%) chose hobbies and personal therapist. Seventeen participants indicated hobbies (15.2%; 95% CI 9.7-23.0%), and 22 respondents (19.6%; 95% CI 13.3-28.0%) mentioned discussions with family members and friends. Religion as main support was cited by only one participant, and personal therapist was never chosen as a single coping strategy.

When asked about the ‘availability of institutional support and debriefing opportunities’ (Table 1, Q6, several answers could be given), 51 (45.5%; 95% CI 36.6-54.8%) respondents indicated the availability of routine debriefings after difficult decision making processes; 12 HCPs (10.7%; 95% CI 6.2-17.8%) named routine team debriefings under the moderation of specially trained moderators whereas 75 participants (67.0%; 95% CI 57.8-75.0%) answered that they have the possibility to hold team discussions without the help of a trained moderator. Forty-three HCPs (38.4%; 95% CI 29.9-47.6%) also mentioned the assistance to the neonatal team from the hospital’s pastoral care. Finally, 14 respondents (12.5%; 95% CI 7.6-19.9%) indicated no routinely implemented institutional assistance available to relief the work-related burden.

DISCUSSION

A comparison of the low prevalence of work-related stress in our survey with other reports focusing on burnout is not possible as we did not formally assess burnout. We aimed more at stress recognition among NICU caregivers, given the fact that burnout could be described as a process which begins with sustained high levels of stress which can ultimately lead to a feeling of fatigue, emotional exhaustion, detachment, irritability and cynicism [21]. In our study we explored only two elements of burnout, namely exhaustion and relationship deterioration included in most burnout questionnaires. The large variability of burnout prevalence ranging from 7.5% to 86% in healthcare workers including two NICUs [20,21] might depend on the burnout questionnaire used and on the cultural and socio-demographic conditions of the interviewed samples.

Our study focused on coping strategies but further protective factors associated with lower stress related disturbances were not specifically assessed. Neonatal physicians and nurses in our cohort dealt with this professional stress by primarily talking to family members and friends, and/or by finding stress relief through their hobbies. These finding are consistent with the results from other studies [24-26]. Regular exercise has been advocated to relieve stress in critical care givers [17], the same holds true for having outside interests and hobbies [27].

Close to 90% of the respondents of our survey indicated that they were offered some form of debriefings, discussion platforms or assistance by the hospital. Staff meetings have been perceived as important interventions for relieving the job strain and personal stress of the HCPs [28,29]. These unit-level discussions among the staff may also impact on the rating of interpersonal relationships between clinicians and nurses, and on the degree of ICU conflicts, both of which have been found to be associated with increased job strain [28,30] and burnout [31]. Oehler et al., [19] found out, that besides the workload and the dying of the patient, the uncertainty regarding the treatment choices and also conflicts with physicians represent the highest stressors for the nursing staff. This underscores the relevance of facilitating discussions between neonatal physicians and nurses whenever needed. Such strategies will thereby contribute to improve the working conditions, which in turn correlate with positive coping strategies among HCPs, as shown by Golbasi and collaborators [32].

This study has some limitations. For practicality reasons, we focused on the NICUs in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and thereby we included nine out of the total 11 NICUs. Therefore our results cannot be extrapolated to the whole country. Being an explorative pilot survey, we used a non-validated brief six-item questionnaire in order to keep the time burden minimal for respondents. Although satisfactorily high, the response rate of 77% of eligible nurses and doctors bears potential for bias. The direction of such a bias, if present at all, may be that more stressed HCPs were more inclined to participate in this survey. If this would have been the case, we would then have expected a higher prevalence of work-related burden in our sample. Moreover and in order to assess the duration of the work-related burden as subjectively perceived by each respondent, we have not given a precise definition of the duration. As our aim was to focus on the individuals (neonatal clinicians and nurses), we did not collect data such as work environment and conditions, work load, adequacy of staff resources, safety and teamwork climate, and the degree of NICU conflicts. Being a descriptive study, it can therefore not determine a causal relationship between the measured variables.

CONCLUSION

COMPETING INTERESTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

APPENDIX

REFERENCES

- Doyle LW, Anderson PJ (2010) Adult outcome of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics 126: 342-351.

- Johnson S, Marlow N (2014) Growing up after extremely preterm birth: lifespan mental health outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 19: 97-104.

- Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, Samara M, EPICure Study Group (2005) Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med 352: 9-19.

- Mercier CE, Dunn MS, Ferrelli KR, Howard DB, Soll RF, et al. (2010) Neurodevelopmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants from the Vermont Oxford network: 1998-2003. Neonatology 97: 329-338.

- Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, Green C, Higgins RD, et al. (2008) Intensive care for extreme prematurity--moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med 358: 1672-1681.

- Claas MJ, Bruinse HW, Koopman C, van Haastert IC, Peelen LM, et al. (2011) Two-year neurodevelopmental outcome of preterm born children ≤750 g at birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 96: 169-177.

- Smith LK, Draper ES, Field D (2014) Long-term outcome for the tiniest or most immature babies: survival rates. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 19: 72-77.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, et al. (2010) Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 126: 443-456.

- Tagin MA, Woolcott CG, Vincer MJ, Whyte RK, Stinson DA (2012) Hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166: 558-566.

- Green J, Darbyshire P, Adams A, Jackson D (2014) A burden of knowledge: A qualitative study of experiences of neonatal intensive care nurses’ concerns when keeping information from parents. J Child Health Care.

- Azoulay E, Herridge M (2011) Understanding ICU staff burnout: the show must go on. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184: 1099-1100.

- Cavaliere TA, Daly B, Dowling D, Montgomery K (2010) Moral distress in neonatal intensive care unit RNs. Adv Neonatal Care 10: 145-156.

- Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Pochard F, Azoulay E (2007) Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care 13: 482-488.

- Mealer ML, Shelton A, Berg B, Rothbaum B, Moss M (2007) Increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 693-697.

- Merlani P, Verdon M, Businger A, Domenighetti G, Pargger H, et al. (2011) Burnout in ICU caregivers: a multicenter study of factors associated to centers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184: 1140-1146.

- Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Timsit JF, et al. (2007) Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 698-704.

- Fields AI, Cuerdon TT, Brasseux CO, Getson PR, Thompson AE, et al. (1995) Physician burnout in pediatric critical care medicine. Crit Care Med 23: 1425-1429.

- Braithwaite M (2008) Nurse burnout and stress in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care 8: 343-347.

- Oehler JM, Davidson MG (1992) Job stress and burnout in acute and nonacute pediatric nurses. Am J Crit Care 1: 81-90.

- Bellieni CV, Righetti P, Ciampa R, Iacoponi F, Coviello C, et al. (2012) Assessing burnout among neonatologists. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 25: 2130-2134.

- Profit J, Sharek PJ, Amspoker AB, Kowalkowski MA, Nisbet CC, et al. (2014) Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual Saf 23: 806-813.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, et al. (2012) Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 172: 1377-1385.

- West CP, Shanafelt TD (2007) Physician well-being and professionalism. Minn Med 90: 44-46.

- Plante J, Cyr C (2011) Health care professionals’ grief after the death of a child. Paediatr Child Health 16: 213-216.

- Robbins I (1999) The psychological impact of working in emergencies and the role of debriefing. J Clin Nurs 8: 263-268.

- Strote J, Schroeder E, Lemos J, Paganelli R, Solberg J, et al. (2011) Academic emergency physicians’ experiences with patient death. Acad Emerg Med 18: 255-260.

- Penn CL (2010) Physicians’ alter egos. Hobbies relieve stress and allow self expression. J Ark Med Soc 107: 56-58.

- Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, Soares M, Rusinová K, et al. (2009) Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 853-860.

- Pines A, Maslach C (1978) Characteristics of staff burnout in mental health settings. Hosp Community Psychiatry 29: 233-237.

- Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, Eldredge DH, Oakes D, et al. (1997) Nurse-physician collaboration and satisfaction with the decision-making process in three critical care units. Am J Crit Care 6: 393-399.

- Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, Kentish N, Pochard F, et al. (2007) High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 686-692.

- Golbasi Z, Kelleci M, Dogan S (2008) Relationships between coping strategies, individual characteristics and job satisfaction in a sample of hospital nurses: cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud 45: 1800-1806.

Citation: Hauser N, Natalucci G, Bucher HU, Klein SD, Fauchère JC (2015) Work-Related Burden on Physicians and Nurses Working in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A Survey. J Neonatol Clin Pediatr 2: 013.

Copyright: © 2015 Fauchère JC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.