ABSTRACT

Background: Stigma is one of the social barriers for People Living with HIV (PLHIV) to be involved in the community activities. The HIV stigma index study in Yemen in 2012 reported that all the interviewed men and women presented in HIV treatment centers experienced some form of stigma because of their HIV status. The study gave only national figures.

Objective: The aim of this paper is to describe the social stigma and work discrimination of PLHIV in Mukalla city in Hadramout governorate (South-East of Yemen) regardless to their access to treatment centers.

Methods: It is a qualitative study to collect in depth data from PLHIV in Mukalla city through one Focus Group Discussion (FGD) in April 2014. A total of 20 PLHIV (males and females) participated in the FGD within period of two hours. Data collected through FGD were of three parts: social identification, their experience with the discrimination and how to be engaged in the community in a productive way and suggest a work project.

Results: Job discrimination clearly identified: two of them out from their job due to their health status, other form of discrimination reported is medical discrimination. Although all participants spoke frankly with their painful experience of social stigma, but they have interest to do productive work and engaged in the community if they were supported.

Conclusion: Job discrimination for PLHIV is still practiced. Medical discrimination inhibits PLHIV to get their medical human rights. Stigma inhibits engagement of PLHIV within the community. Engagement of PLHIV in the community needs no more than training and small project’s fund otherwise huge and in-depth studies being unethical unless targeted the capacity of PLHIV for sustainable development.

KEYWORDS

AIDS; Hadramout; PLHIV; Yemen

Introduction

AIDS is a syndrome of acquired immune deficiency due to infection with HIV virus through multiple sources. HIV/AIDS related stigma (H/A stigma) is invoked as a persistent and pernicious problem in any discussion about effective responses to the epidemic [1]. Stigma is one of the social barriers for People Living with HIV (PLHIV) to be involved in the community activities.

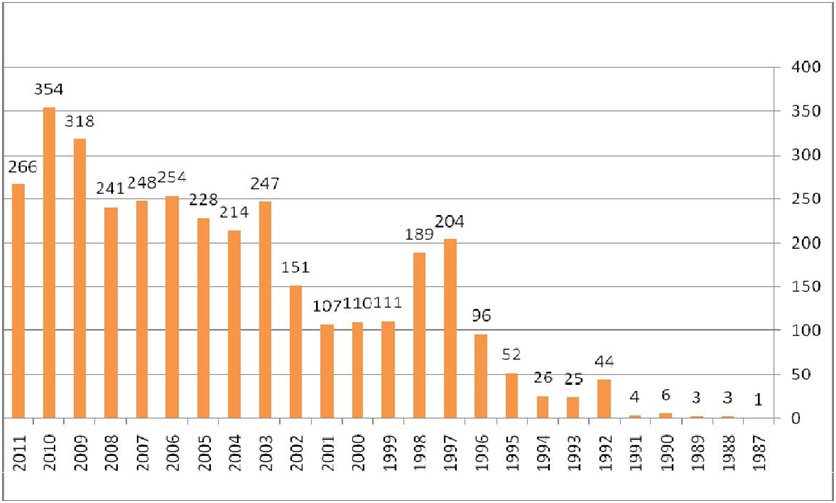

AIDS epidemiology in Yemen indicated of growing problem: in the end of December 2011, a total of 3,502 cases were reported to National Aids Program (NAP) in the Ministry of Public Health and Population (MOPHP) (Figure 1). However, the estimated number of HIV cases in republic of Yemen is 30,000 (2011 HIV size estimates/NAP). The HIV cases reports in 2011 showed that 34% were females and that around 81% of all the cases were aged 15-49 years [2].Although Yemen is one of the countries with low prevalence of HIV (0.2%) in the general population according to 2011 HIV size estimates/NAP [3] the majority of HIV transmission in Yemen is attributed to sexual transmission whether hetero- (62%) or homo-sexual (7%) among new infections [4] but the risk extend beyond those use safe or unsafe sex or like children and patient need blood transfusion. More tragedy is for women and children when infection transmitted from their husbands and fathers. Young people and marginalized people are at more risk due to exploitation [2].

The HIV stigma index study in Yemen [4] reported that all the interviewed men and women experienced some form of stigma because of their HIV status e.g., exclusion from social, family or religious activities, the study reported some forms of discrimination like: change the residence or can no rent place due to HIV status.

As a small proportion was not in official employment, small number lost their jobs or changed in job nature because of the HIV stigma or poor health. Also stigma extended to the families of the PLHIV [4].

Hadramout is one of eastern governorates of Yemen. The total population of Hadramout is 1,329,000 persons in 2012 [5]. Hadramout governorate consists of two parts: the first part is the desert/valley; the second part is the costal districts.

Mukalla city is a main sea port and the capital city of the Hadramout coastal region in Yemen, it is located 480 km east of Aden. Mukalla is the fifth largest city in Yemen with a population of approximately 300,000 [5,6].

The official body for AIDS surveillance and prevention in Hadramout is the office of National Aids Control Program (NAP) where it is located in Mukalla. The program reported an accumulative of 300 AIDS cases from 2000 to 2013 in Hadramout coastal districts (14 districts including Mukalla city district) with increasing annual incident cases from 19 cases in 2012 to 45 cases in 2013. In 2013, it was reported 45 new cases (34 males and 11 females) most of them from Mukalla city (24 cases). Local cases are increased from 17 cases in 2012 to 42 cases in 2013 [5]. (Local cases means Yemeni patients from Hadramout governorates).

The HIV stigma index study [6] in five governorates in Yemen including Mukalla city that is conducted by UNAIDS in 2012 collected data about 163 PLHIV (females: 77, males: 86) who are in contact with the treatment centers but the silent PLHIV may live in a worse hardship. The findings were of national figures.

In Hadramout the discussion of issues related to HIV is still of sort of social forbidden and this hidden problem need to be sensitized within the scientific and professional community including HIV screening, medical rights and PLHV social empowerment. The aim of this paper was present the social stigma and work discrimination of PLHIV in Mukalla city regardless to their access to treatment centers.

Methods

It is a qualitative study to collect in depth data from PLHIV in Mukalla city through one Focus Group Discussion (FGD) in April 2014. A total of 20 PLHIV (12 males and 8 females) participated in the FGD within period of two hours. The FGD was coordinated by the investigator, reported by another one reporter using tape recorder and the pen and paper. The NAP coordinator in Mukalla was participated as a consultant to answer any questions raised by participants related to NAP activities. Data collected through FGD are of three parts: social identification, their experience with the discrimination and how to be engaged in the community in a productive way and suggest a work project.

In the FGD; the author and the reporter explained to participants the mechanism of the discussion, using tape recorder for record the discussion. Then the author open the FGD by starting a question then give every participant to talk about his/herself; their experience, suffering and opinions and their vision for the future to be productive in the community. The discussion was in Arabic. Finally, the data collected were grouped in themes, translated to English language, re-organized and summarized and accordingly presented. Some talks are translated and presented as it is in boxes in the result’s section.

Ethical consideration

Because of the special situation of PLHIV and some of them being not in contact with treatment centers, participants were informed some days before the FGD about the purpose of the meeting by the NAP coordinator and those who agree were invited to participate.

Results

Social identification

Regarding their jobs some have private job and others are non-employee: types of jobs mentioned as: taxi or bus drivers, mobile technicians, cleaner but all females are housewives and being wives of some of the participants. The discrimination here identified regarding their job: two participants lost their jobs due to their HIV status.

How to be engaged in the community in a productive way and suggest a work project?

All participants spoke frankly with their painful experience of social stigma, one prefer to travel out of Yemen to avoid this stigma but others have interest to work normally if they get financial support, they have multiple work experience. The females suggest do some working at home and selling it to the people like light meals preparation, HENNA for women.

All women request training courses to improve their family income through acquiring manual skills of HENNA and other works.

| If I have two hundred thousand Yemeni Ryal; I will do a project of light meal preparation in schools or other places in the market (one of participants said). | | Other participant said “I will open a store of kitchen gas cylinders to sell to the people.” |

Their experience with the discrimination

It was a painful experience, one participant talk about how he is afraid about the stigma and how other look at him as he came from other country out of Yemen and return back to Yemen because of his disease, it is a painful experience. Moreover other form of discrimination reported was the medical discrimination when PLHIV seek medical care.

| If I did not disclose my HIV status; doctor can accept me for surgical care; this is what happen for me in one surgery clinic. (one participants aid). | | The surgeon refused to do for me Hemorroidectomy just he discovered my HIV status (one participant said). |

Discussion

Although the study was limited to a few numbers of PLHIV, but give a clue to their suffering even as struggle to be engaged productively in their community. They are families (some of them are husband and wife and their children being PLHIV), they have a vision and skills to be productive even housewives. Disclosure of HIV status is a clogged reason for PLHIV engagement in the community. The study discovered the extent of the lack of legislative protection to maintain their jobs, non-compliance of medical doctors regarding medical rights of the PLHIV. Stigma is one of the social barriers for People Living with HIV (PLHIV) to be involved in the community activities. Dos Santos et al., [7] suggested that PLHIV in South Africa population experience significant levels of stigma and discrimination that negatively impact on their health, working and family life, as well as their access to health services. Moreover higher levels of stigma and discrimination against PLHIV were observed among health care providers in Ethiopia [8]. In addition to devastating the familial, social, and economic lives of individuals, H/A stigma is cited as a major barrier to accessing prevention, care, and treatment services [1].

Numerous studies have documented the attitudes of healthcare providers toward PLHIV [9-14]. Although the literature characterizes the attitudes and behaviors of healthcare providers as positive and respectful, many studies also report poor communication between patients and healthcare providers [15], which functions as a major barrier in providing proper care for these patients [16]. Few studies in the international body of literature explore the experiences of PLHIV in the context of the healthcare system. One recent cross-sectional study, conducted among a sample of 202 PLHIV in Los Angeles Country, US, demonstrated that in a diverse and under-served sample of PLHIV, poor access (self-reported) to medical care is strongly associated with experiencing HIV stigma [17].

Regarding job discrimination; global and regional surveys indicate the existence of high levels of employment discrimination based on HIV status worldwide, including forced disclosure of HIV status, exclusion in the workplace, refusals to hire or promote, and terminations of people known to be living with HIV [18].

Conclusion

The following forms of stigma and discrimination were identified:

1: Job discrimination

2: Medical discrimination inhibits PLHIV to get their medical human rights

3: Stigma inhibits engagement of PLHIV within the community.

Engagement of PLHIV in the community need no more than training and small project’s fund otherwise huge and in-depth studies being unethical unless targeted the capacity of PLHIV for sustainable development.

Acknowledgment

This is part of project that received technical and financial support from the UNAID office in Sana’a (Yemen) in 2013 under the title of “Community awareness and social empowerment of People Living with HIV (PLHIV): Role of stigma and discrimination related to HIV in Hadramout governorate” with collaboration of MOPHP office in Hadramout. Here the author expresses his great appreciation for this support. The author thanks Dr. Fowzia Gramah (The UNAID officer in Yemen, Amal Muressi (The administrative director of UNAID in Yemen) for their support) and the NAP coordinator in Hadramout for his great efforts in communication with the participants.

Figures

Figure 1: Incidence of Reported Cases by Year in Yemen (1987 - 2011) [2].