Recruitment and Retention of Participants from Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in the First Phase I HIV Vaccine Trial in this Community: Experiences of the EV06 Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Annet NanvubyaUvri Iavi Hiv Vaccine Program, Entebbe, Uganda

Tel:+256 772592717, +256 772722377

Email:ananvubya@iavi.or.ug

Abstract

Fishing communities are a new “Most at Risk Population for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa”. If they are to successfully participate in HIV prevention trials, researchers must demonstrate that they can recruit and retain them in these trials. We assessed the recruitment and retention rates of the first phase 1 HIV vaccine trial among fishing communities in Uganda.

Methods

Adult participants (18-45 years) identified through community education seminars on the shores of Lake Victoria and surrounding villages were invited to two study clinics in Entebbe and Masaka, Uganda for screening and possible enrolment into a randomized control HIV Vaccine trail. Detailed study information was given and written informed consent obtained from each participant. Eligibility for enrolment was based on low HIV risk profile, helminthic status, demonstration of understanding of the study, availability for 9 months’ follow-up, contraceptive use and clinical and laboratory assessments. Proportions of volunteers screened, enrolled and followed up were measured. Proportions of reasons for screen failure were also measured.

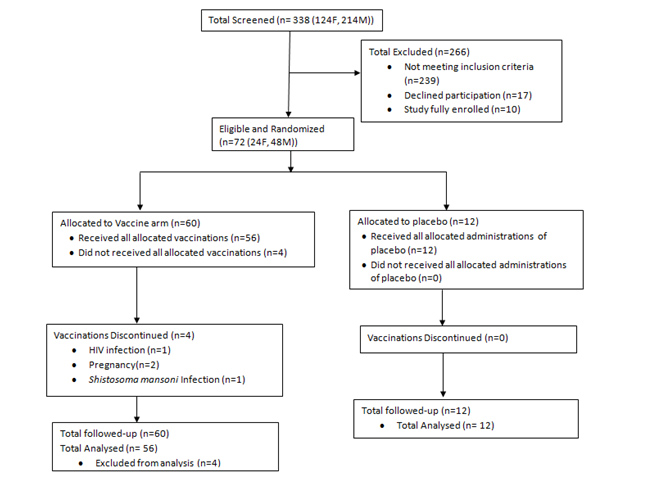

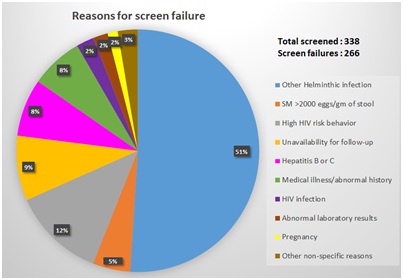

Recruitment took approximately 6 months between November 2014 and April 2015. A total of 338 participants (124, 37% females) were screened to enroll 72 (24, 33% females) giving a screening to enrolment ratio of 5:1. Screen failure reasons included; helminthic infection (153, 51%), high HIV risk behavior (37, 12%), unavailability for follow-up (26, 9%), hepatitis B or C infection (23, 8%), medical illness/abnormal history (21, 7%), HIV infection (7, 2%), abnormal laboratory results (6, 2%), pregnancy (4, 1%) and other reasons (8, 3%). A retention rate of 100% was achieved at the end of the 9 months’ follow-up.

We conclude that despite a substantial proportion of screen failures, it was possible to recruit and retain participants in the first ever HIV vaccine trial from a community that is quite mobile and at high risk of HIV-1 infection. It is important to engage fishing communities in HIV prevention research as this key population will help researchers better understand the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Uganda.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The first HIV case in Africa was reported in a fishing community in Uganda 37 years ago [1]. Fishing communities in Uganda remain key drivers of the epidemic [2,3]. Emerging data indicates that Ugandan fishing communities have HIV infection rates that are three to six times higher than the national average [4-13]. An HIV vaccine in addition to other biomedical prevention strategies is urgently needed. As progress continues to be made in the development of HIV vaccines, fishing communities are among the unique populations being prepared to participate in HIV prevention trials. The conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials however, requires populations with individuals that can be retained after enrolment into clinical trials. People from fishing communities tend to be mobile in search of better fish catch, which tends to be seasonal [14]. The fishing industry is also largely a cash business, so fishermen and individuals working in related professions (i.e., fish mongers, fish smokers, and others) often have access to disposable income or cash which they often spend on purchasing alcohol or commercial sex [14]. Fishing commonly attracts younger men who are working away from their homes and may be socially isolated from their families and social networks, which has been found to contribute to risk-taking behaviors such as drinking alcohol and commercial sex, high mobility, disposable income and younger age demographics all contribute to making fishing community residents particularly vulnerable to concurrent multiple sexual partnerships which increase exposure to HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Additionally, because of their mobile nature, high number of pregnancies, high HIV infection rates and busy work schedules [9,15], it may be challenging to recruit and enroll fishing community residents in clinical trials. If fishing communities are to be considered for inclusion in future biomedical HIV prevention research, recruitment and retention strategies that are tailored to suit their needs are needed.

Many fishing communities in Uganda are remotely located and difficult to access [14]. People from these communities have limited access to basic health care services and are hence characterized by several prevalent infections and infestations, which on many occasions go untreated [5,6,16]. Because participation in clinical research requires healthy individuals, these conditions may make it difficult for people from fishing communities to participate in biomedical HIV prevention research. Participant attrition is a major factor that impacts the internal validity of interventional studies [17]. Because individuals from these communities are mobile in nature, retention strategies that suit their mobility patterns are needed. This is because participant loss in research has negative impacts on research findings such as reduction in statistical power and may confound the inference on effects of an intervention on specific outcomes [18]. Before more clinical trials are conducted in fishing communities, it is worthwhile to determine whether people from these communities can be recruited and retained in trials.

We conducted a phase 1 HIV vaccine trial in fishing communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda called the EV06 trial and we report our experiences on recruitment and retention of participants this trial. It is noteworthy that early phase trials tend to have more intensive follow up schedules and enrolling fishing communities in such trials is a significant step toward including this unique population in HIV prevention efforts.

The EV06 trial was a collaborative trial between the European Community’s FP7 IDEA program, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and the Uganda Virus Research Institute. It was the first phase 1 HIV vaccine trial conducted that enrolled residents of fishing communities. It recruited individuals in the community who were at low risk for HIV infection. The main objective of the trial was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of the combination of DNA-HIV-PT123 and AIDSVAX®B/E vaccines in HIV-1 uninfected adults with or without Schistosoma mansoni infection while assessing the effect of prevalent Schistosoma mansoni infection on the immunogenicity of the vaccines. For this manuscript, we report the recruitment and retention outcomes of this trial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The study recruited HIV negative, male and female participants aged 18-45 years, who were at low risk for HIV. Being at high risk for HIV infection (within 3 months prior to the first vaccination) was collected by participant self-report and defined by reporting of at least one of the following: Unprotected sexual intercourse with an HIV-infected person, a partner known to be at high risk of HIV infection or a casual partner (i.e., no continuing established relationship), unprotected sexual intercourse with more than one sexual partner, engagement in sex work for money or drugs, use of recreational drugs (e.g., marijuana) and/or weekly or more frequent alcohol use and current or past Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI).

Recruitment and retention methods

Eligibility for enrolment was based on HIV risk profile, age, helminthic infection status, demonstration of understanding of the study, availability for 9 months’ follow-up, willingness to use an effective contraceptive method and delay pregnancy until end of the study, and on clinical and laboratory assessments. For the Schistosoma positive group, participants infected with only Schistosoma mansoniwith an egg count below 2000 eggs per gram of stool and no other helminthes were enrolled. For safety reasons, participants with high intensity schistosomiasis of ≥ 2000 eggs per gram of stool were excluded because they needed urgent treatment. In order to minimize the risk of infection with Schistosoma mansoni during the trial, participants without Schistosoma mansoni were only recruited from communities at least 5 km from the lake shore where the prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni was expected to be low. Participants with Schistosoma mansoni infection were recruited from fishing villages along the shores of Lake Victoria where the prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni infection is high. All those who were excluded received appropriate treatment and referrals.

Considering that this is a mobile community, additional recruitment and retention strategies were employed in recruitment and implementation phase. Community Advisory Board (CAB) members are normally engaged in the recruitment of study participants in clinical trials. Unlike in trials involving the general population where 3 to 4 CAB meetings are conducted, i14 CAB meetings were conducted in this study to ensure that more community members were approached. Community gate keepers helped in tracing study participants who had migrated. Contact information including home addresses, work addresses and telephone contacts was collected at screening for purposes of locating participants if needed. During study implementation, continuous telephone call reminders and home visits were made to ensure that participants attended their visits on schedule. Participants were reminded by telephone calls of an upcoming visit 7 days and again 3 days prior to the scheduled visit date or just before the scheduled visit date. Participants were reimbursed for time and transport at each visit depending on where they stayed.

Study design

Study duration

Sample size

Data collection

Biological sample collection

Data analysis

Study monitoring

Ethical considerations

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics

|

Characteristic |

N |

Male |

Female |

|

Total |

72 (100%) |

48 (66.7%) |

24 (33.3%) |

|

Age (years) |

|||

|

Mean (SD) |

29.6 (6.2) |

28 (5.6) |

32 (6.7) |

|

Median (IQR) |

29 (21-42) |

28 (23-33) |

31 928-37) |

|

18-24 |

21 (29%) |

19 (39%) |

2 (8.3%) |

|

25-34 |

35 (49%) |

21 (44%) |

14 (58.4) |

|

35+ |

16(22%) |

8 (17%) |

8 (33.3%) |

|

Highest Education level |

|||

|

None |

0(0%) |

|

|

|

Primary |

66 (91.7%) |

43 (89.6%) |

23 (95.8%) |

|

Secondary |

6 (8.3%) |

5 (10.4%) |

1 (4.2%) |

|

University/Tertiary |

0 (0%) |

|

|

|

Residence |

|||

|

Lake shore |

35 (48.6%) |

23 (47.9%) |

12 (50%) |

|

Mainland |

37 (51.4%) |

25 (52%) |

12 (50%) |

|

Employment |

|||

|

Not employed |

2 (2.8%) |

0 |

2 (8.3%) |

|

Fishing and related tasks |

3 (4.2%) |

1 (2.1%) |

2 (8.3%) |

|

Business/Trade |

48 (66.7%) |

36 (75%) |

12(50%) |

|

Farming |

6 (8.3%) |

3 (6.3%) |

3 (12.5%) |

|

Other Jobs |

13 (18%) |

8 (16.7%) |

5 (20.8%) |

|

Marital Status |

|||

|

Married/Living Together |

27 (37.5%) |

21(43.8%) |

6 25%) |

|

Divorced/Separated |

3 (4.2%) |

1 (2%) |

2 (8.3%) |

|

Not Married/Single |

42 (58.3%) |

26 (54.2%) |

16 (66.7%) |

|

Religion |

|||

|

Christian |

52 (72) |

37 (77) |

15 (63) |

|

Muslim |

20 (28) |

11 (23) |

9 (37) |

Table 1: Social demographic characteristics of study population.

Recruitment and retention

Figure 1: Number of individuals screened for eligibility, enrolled and followed-up.

Figure 1: Number of individuals screened for eligibility, enrolled and followed-up.Reasons for screen failure

Figure 2: Reasons for screen failure.

Figure 2: Reasons for screen failure.DISCUSSION

This was the first HIV vaccine trial that recruited individuals from fishing communities. Although fishing communities are known to be a mobile population in Uganda, the EV06 trial demonstrated that it was possible to recruit and retain participants in an early phase trial [12]. The duration of recruitment was longer than expected because of the rather stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria that were followed. For example, one unique criterion was that in the Schistosoma positive group, participants infected with only Schistosoma mansoni with an egg count below 2000 eggs/gram of stool and no other helminths were eligible to be enrolled. The high prevalence of worm infections in this population contributed to the long recruitment period and high screening: Enrolment ratio. Despite the longer than expected duration of recruitment a retention rate of 100% was registered at each of the fourteen study visits.

Approximately one third of the participants enrolled in the study were females. It is worthwhile to note that requirements for participation in this clinical trial made it easier to enroll male participants as compared to their female counterparts. Females of reproductive potential were required to use effective birth control methods to avoid getting pregnant while on the study to avoid potential unknown effects of the study products to an unborn child. Breast feeding mothers were also excluded from participation in the trial. As in other early phase HIV vaccine clinical trials, four pregnant women, two intending to get pregnant, two breast feeding mothers and three reproductive women who were not willing to use contraception were excluded [19]. Previous literature shows that female participants especially from resource limited settings often lack the autonomy to make independent decisions to participate in biomedical interventions [20,21]. It is common that women have to first seek consent from their spouses prior to participation. In view of these gender disparities, it is understandable that more males than females in this study were enrolled, a trend that has been observed in other HIV prevention studies [16,21]. In another HIV vaccine trial that we conducted in the general population, the proportion of women compared to male participants was similar to that in this trial [22]. Whereas recruitment of women in clinical trials is challenging, it is important to recruit a near-equal proportion of male and female participants both to understand the safety profile of the investigational products on men and women and also maintain the ethical integrity of the trial, as women bear the greatest burden of the HIV epidemic.

Even though the required age of participation ranged between 18-49 years, the majority of the participants were adults between the ages of 25-34 years. This probably was a reflection of the demographics of the population where the 25-34 age groups were most prevalent. Another HIV vaccine trial which was conducted in the general population revealed a similar age distribution [22]. Findings from our study also show that only a few adults aged over 35 years participated in the study. Another study conducted by Joako et al. which recruited from an urban population including university students, showed that majority of those who participated in that HIV vaccine trial were adults aged below 35 years [23]. Since these two trials targeted different study populations, it is possible that individuals aged 18-24 years and those aged 35 years and over are more difficult to engage in clinical trials, and more information is needed to try and actively engage them.

In this study, retention did not differ by geographic location because retention of 100% at all the fourteen visits was accrued in both study groups. The retention was higher than what was previously observed in a study which assessed recruitment and retention of women in Ugandan fishing communities [21]. Nevertheless, the retention was similar to what was observed in a vaccine trial that we conducted in the general Ugandan population [22]. Given that our population is known to be mobile, we attribute this high level of retention to the rigorous recruitment and retention strategies that were employed.

Studies conducted in similar settings have shown that most of the residents in fishing communities have little or no formal education [5,7,10,21,23-28]. Similarly, majority of the participants in our study had attained only up to primary education level. This however did not impact recruitment or retention in the study. Illiterate participants were consented in the local language in the presence of an impartial witness which made it possible for them to comprehend the study and its requirements. Because of their low literacy rates, vaccine and trial concepts were explained with use of visual aids where necessary.

The screening: Enrolment ratio in trials involving the Ugandan general population or non-fishing communities is noted to be lower (2:1) as compared to what it was in this study (5:1). The high number of screen outs was mainly due to the stringent eligibility criteria with regard to the Schistosoma infection status; the high proportion of individuals at high risk for HIV and other co-morbidities. Participants with a Schistosoma mansoni egg count of >2000 eggs per gram of stool and other helminthic infections were excluded. People from near water bodies tend to have Schistosoma and other worm infections which usually go untreated [28]. As they go out fishing with continuous exposure to water, they get infected with worms, so many were excluded due to a high worm burden.

People from fishing communities have a high rate of multiple sexual partnerships which puts them at a higher risk for HIV [10,29]. Because of this, many were excluded from participation in the clinical trial which required individuals at low risk for acquiring HIV. Additionally, a high prevalence of undiagnosed chronic medical conditions such as Hepatitis, syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases contributed to the high screen failure rate. Fishing communities tend to be limited in regards to basic health care services [20,30]. They lack social structures such as schools and hospitals, hence forth; they are burdened with different morbidities. In future, researchers need to address the prevailing health challenges through provision of basic health services to communities where research participants will be drawn from.

The residence status also contributed to the high screening: Enrolment ratio in this study and the long recruitment duration. Since the trial recruited participants without Schistosoma mansoni from a pre-set distance of at least 5 km away from the lake shore while participants with a low burden of Schistosoma mansoni were recruited from communities along the lake shore, many would be eligible participants were excluded. Recruitment for HIV vaccine trials evaluating vaccine candidates for safety doesn’t routinely exclude participants based on their residence status. Other studies which recruited participants from non-fishing communities and had no residence restrictions recruited in a much shorter duration [23,31,32].

People from fishing communities are known to be mobile as majority tends to be fishermen who keep moving from one fishing community to another in search for fish [11]. In this study, we were able to demonstrate that regardless of their mobile nature, people from fishing communities can be recruited and retained in a trial. A similarly good retention was observed in other mobile and high risk populations [33,34]. However, to get such retention, the study team employed additional measures such as conducting more CAB meetings, engaging CAB members in recruitment, making continuous and consistent reminders through telephone calls and home visits when telephones were off.

While results in this study show that fishing communities can be successfully recruited and retained in clinical trials, findings may have been different if participants at high risk for HIV had been recruited. Recruitment and retention of high risk individuals from this community still need to be assessed.

CONCLUSION

Findings from the EV06 trial show that, despite a substantial proportion of screen failures, it is possible to recruit for early phase HIV prevention vaccine trials in fishing communities and have a high retention rate. Although the majority of the screen failures were due to helminthic infections, this screening criterion is not normally included in HIV vaccine clinical trials. Despite their mobile nature, fishing community residents can adhere to clinical trial procedures similar to individuals in the general population. It is important to engage fishing communities in HIV prevention research as this key population will help researchers better understand the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Uganda and assess new prevention technologies in clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We appreciate the study participants, study staff and all other key stakeholders for their valuable contribution. We appreciate the following; a) UVRI-IAVI HIV Vaccine Program Limited and MRC/UVRI Uganda Research Unit for supporting the implementation of the study and for providing institutional and logistical support; b) Study participants for providing the data; c) Study staff for collecting the data; d) UVRI-Research and Ethics Committee and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology for reviewing the study; and e) UVRI-IAVI Community Advisory Board for their continuous advice, support and guidance throughout the implementation phase.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The dataset used and/or analyzed for this study are available from the corresponding author on request. All authors have given their consent to publish this work and have made contributions in various capacities.

REFERENCES

- Serwadda D, Mugerwa RD, Sewankambo NK, Lwegaba A, Carswell JW, et al. (1985) Slim disease: A new disease in Uganda and its association with HTLV-III infection. Lancet 2: 849-852.

- Kamali A, Nsubuga RN, Ruzagira E, Bahemuka U, Asiki G, et al. (2016) Heterogeneity of HIV incidence: A comparative analysis between ?shing communities and in a neighbouring rural general population, Uganda, and implications for HIV control. Sex Transm Infect 92: 447-454.

- Kiwuwa-Muyingo S, Nazziwa J, Ssemwanga D, Ilmonen P, Njai H, et al. (2017) HIV-1 transmission networks in high risk fishing communities on the shores of Lake Victoria in Uganda: A phylogenetic and epidemiological approach. PLoS One 12: 0185818.

- Opio A (2010) HIV sero-behavioural study in the fishing communities along lake victoria in uganda. East African Community, United Republic of Tanzania, Tanzania.

- Asiki G, Abaasa A, Ruzagira E, Kibengo F, Bahemuka U, et al. (2013) Willingness to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials among high risk men and women from fishing communities along Lake Victoria in Uganda. Vaccine 31: 5055-5061.

- Asiki G, Mpendo J, Abaasa A, Agaba C, Nanvubya A, et al (2011) HIV and syphilis prevalence and associated risk factors among fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sex Transm infect 87: 511-515.

- Seeley J, Tumwekwase G, Grosskurth H (2009) Fishing for a living but catching HIV: AIDS and changing patterns of the organization of work in fisheries in Uganda. Anthr Work Rev 30: 66-76.

- Seeley J, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kamali A, Mpendo J, Asiki G, et al. (2012) High HIV incidence and socio-behavioral risk patterns in fishing communities on the shores of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis 39: 433-439.

- Kissling E, Allison EH, Seeley JA, Russell S, Bachmann M, et al. (2005) Fisherfolk are among groups most at risk of HIV: Cross-country analysis of prevalence and numbers infected. AIDS 19: 1939-1946.

- Kiwanuka N, Ssetaala A, Mpendo J, Wambuzi M, Nanvubya A, et al. (2013) High HIV-1 prevalence, risk behaviours, and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials in fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc 16: 18621.

- Kiwanuka N, Ssetaala A, Nalutaaya A, Mpendo J, Wambuzi M, et al. (2014) High incidence of HIV-1 infection in a general population of fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS One 9: 94932.

- Kiwanuka N, Mpendo J, Nalutaaya A, Wambuzi M, Nanvubya A, et al. (2014) An assessment of fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda, as potential populations for future HIV vaccine efficacy studies: An observational cohort study. BMC Public Health 14: 986.

- Opio A, Muyonga M, Mulumba N (2013) HIV infection in fishing communities of Lake Victoria Basin of Uganda--a cross-sectional sero-behavioral survey. PLoS One 8: 70770.

- Seeley JA, Allison EH (2005) HIV/AIDS in fishing communities: Challenges to delivering antiretroviral therapy to vulnerable groups. AIDS Care 17: 688-697.

- Kiwanuka N, Robb M, Kigozi G, Birx D, Philips J, et al. (2004) Knowledge about vaccines and willingness to participate in preventive HIV vaccine trials: A population-based study, Rakai, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 36: 721-725.

- Ruzagira E, Wandiembe S, Bufumbo L, Levin J, Price MA, et al. (2009) Willingness to participate in preventive HIV vaccine trials in a community-based cohort in south western Uganda. Trop Med Int Heal 14: 196-203.

- Kim YJ, Peragallo N, DeForge B (2006) Predictors of participation in an HIV risk reduction intervention for socially deprived Latino women: A cross sectional cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud 43: 527-534.

- Steiner PM, Wroblewski A, Cook TD (2002) Randomized experiments and quasi-experimental designs in educational research. The role of science in educational evaluation Randomized Experiments and Quasi-Experimental Designs.

- Kibuuka H, Guwatudde D, Kimutai R, Maganga L, Maboko L, et al. (2009) Contraceptive use in women enrolled into preventive HIV vaccine trials: Experience from a phase I/II trial in East Africa. PLoS One 4: 5164.

- Kiwanuka N, Mpendo J, Nalutaaya A, Wambuzi M, Nanvubya A, et al. (2014) An assessment of fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda, as potential populations for future HIV vaccine efficacy studies: An observational cohort study. BMC Public Health 14: 986.

- Ssetaala A, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Asiimwe S, Nanvubya A, Mpendo J, et al. (2015) Recruitment and retention of women in fishing communities in HIV prevention research. Pan Afr Med J 21: 104.

- Mpendo J, Mutua G, Nyombayire J, Ingabire R, Nanvubya A, et al. (2015) A phase I double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of the safety and immunogenicity of electroporated HIV DNA with or without interleukin 12 in prime-boost combinations with an Ad35 HIV vaccine in healthy HIV-seronegative african adults. PLoS One 10: 0134287.

- Jaoko W, Nakwagala FN, Anzala O, Manyonyi GO, Birungi J, et al. (2008) Safety and immunogenicity of recombinant low-dosage HIV-1 A vaccine candidates vectored by plasmid pTHr DNA or Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara (MVA) in humans in East Africa. Vaccine 26: 2788-2795.

- Kiwanuka N, Ssetaala A, Ssekandi I, Nalutaaya A, Kitandwe PK, et al. (2017) Population attributable fraction of incident HIV infections associated with alcohol consumption in fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS One 12: 0171200.

- Asiki G, Mpendo J, Abaasa A, Agaba C, Nanvubya A, et al. (2011) HIV and syphilis prevalence and associated risk factors among fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sex Transm Infect 87: 511-515.

- Abaasa A, Asiki G, Mpendo J, Levin J, Seeley J, et al. (2015) Factors associated with dropout in a long term observational cohort of fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda. BMC Res Notes 8: 815.

- Omosa-Manyonyi G, Mpendo J, Ruzagira E, Kilembe W, Chomba E, et al. (2015) A phase I double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of the safety and immunogenicity of an adjuvanted HIV-1 Gag-Pol-Nef fusion protein and adenovirus 35 Gag-RT-Int-Nef vaccine in healthy HIV-uninfected African adults. PLoS One 10: 0125954.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2014) Fisheries and Aquaculture Information and Statistics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- Pickering H, Okongo M, Bwanika K, Nnalusiba B, Whitworth J (1997) Sexual behaviour in a fishing community on Lake Victoria, Uganda. Health Transit Rev 7: 13-20.

- Nanvubya A, Ssempiira J, Mpendo J, Ssetaala A, Nalutaaya A, et al. (2015) Use of modern family planning methods in fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS One 10: 0141531.

- Goepfert PA, Elizaga ML, Sato A, Qin L, Cardinali M, et al. (2011) Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity testing of DNA and recombinant modified vaccinia Ankara vaccines expressing HIV-1 virus-like particles. J Infect Dis 203: 610-619.

- Mugerwa RD, Kaleebu P, Mugenyi P, Katongole-Mbidde E, Hom DL, et al. (2002) First trial of HIV vaccine in Africa: Ugandan experience. BMJ 324: 226-229.

- Celentano DD, Beyrer C, Natpratan C, Eiumtrakul S, Sussman L, et al. (1995) Willingness to participate in AIDS vaccine trials among high-risk populations in northern Thailand. AIDS 9: 1079-1083.

- Hom DL, Johnson JL, Mugyenyi P, Byaruhanga R, Kityo C, et al. (1997) HIV-1 risk and vaccine acceptability in the Ugandan military. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 15: 375-380.

Citation: Nanvubya A, Bahemuka U, Mpendo J, Kibengo F, Ssetaala A, et al. (2019) Recruitment and Retention of Participants from Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in the First Phase I HIV Vaccine Trial in this Community: Experiences of the EV06 Study. J Vaccines Res Vaccin 5: 008.

Copyright: © 2019 Annet Nanvubya, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.