A National Survey of Hospice Aid-in-Dying Policy Availability and the Impact of Legal Mandates

*Corresponding Author(s):

Gianna R StrandColumbia University, New York, United States

Email:grs2144@columbia.edu

Abstract

Context: The field of aid in dying is expanding in the United States. Terminally ill patients face difficulties in navigating this legal process. A combined lack of support by hospice facilities and inability to access end of life policy information limits patients’ ability to make fully informed decisions on where to receive care.

Objectives: The purpose of this article is to survey and report on the current state of publicly available medical aid in dying policy nationally with a focus on hospice facilities and providers.

Methods: A non-exhaustive list of hospice-providing facilities is drawn from two public web directories. The 683 facilities identified in the eleven applicable US jurisdictions were searched for medical aid in dying policy.

Results: Only 28% of facilities in this review post aid-in-dying policy to their web pages. This increases to 50% in California and 42% in Washington. Total policy availability numbers are inflated by the presence of shared policies operated by large corporate care centers and multi-site hospital networks. 98% of policies are clearly titled to assist prospective patients in locating the information.

Conclusions: The legal requirements to post notice of a policy to a public web page in California and Washington are moderately successful in increasing the public availability of end-of-life policies. Similar statutes may be necessary to shift the national standard of practice. However, statutory requirements to post notice do not ensure that policy content is comprehensive, factual, or capable of aiding a terminally ill patient in making decisions regarding their end-of-life care including choice of facility or provider. Analysis of policy content requires further investigation.

Keywords

Health policy; Hospice ethics; Hospice practice Medical aid in dying

Introduction

Medical Aid-in-Dying (MAiD) in the United States is the legal process whereby a terminally ill patient takes prescribed medications following an explicit request with the understanding that the patient intends to self-administer the medications to end their life [1,2]. In 1997, Oregon became the first state to legalize MAiD through their Death with Dignity Act [3]. At present, ten states and the District of Columbia permit MAiD [4]. Globally, 200 million people have legal access to some form of assisted dying in Canada, Columbia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Switzerland, parts of Australia, elsewhere [5]. In the United States, accessing MAiD remains challenging even in jurisdictions where it is legal. Navigating policies and finding providers can prove difficult, particularly for individuals with limited resources and high symptom burdens at the end of life [6]. Although the American Medical Association (AMA) has adopted a position of neutrality that physicians can provide MAiD without violating their professional obligations, 70% of patients who seek assistance from the non-profit End of Life Washington cite difficulties with finding physicians who support aided dying [7-9]. Veterans are excluded from accessing assisted dying unless they can afford private medical care as federal law prohibits VA physicians from participating [10]. There are few evidence-based reviews on the barriers to accessing MAiD to supplement case repots and news media features of patients struggling to find providers, pharmacies, hospice facilities to accept them after making a request for MAiD [11].

Access to MAiD is noticeably constrained when hospice facilities which do not support a patient’s right to request or ingest aid-in-dying prescriptions require the transfer of care to unfamiliar or distant facilities in the final days of life [12]. There is clear interrelation of hospice care and MAiD: over 90% of patients in California, Oregon, Washington are enrolled in hospice at the time of ingestion [13-15]. Multiple states require providers to counsel patients who request MAiD about feasible alternatives including palliative, comfort, hospice care [16,17]. Hospices are not required to support MAiD practices, but failure to clearly disclose a facility policy constrains the ability of prospective terminally ill patients in making fully informed decisions on how to achieve a death in line with their own values [1]. The American Clinicians Academy on Medical Aid in Dying recommends that an aid-in-dying policy statement be posted in a clear, readily accessible, prominent web page location. That policy should use specific language which provides adequate information to staff, clinicians, patients and families [18]. Improving the transparency of health policy information and addressing barriers to access has been the impetus for provisions and amendments to MAiD statutes. New Mexico’s Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act requires health care entities that prohibit MAiD to “accurately and clearly articulate” their opposition on their entity website and in materials given to patients [19]. California amended their End of Life Option Act via Senate Bill No. 380 (SB 380) in January 2022 with a new legal obligation for health care entities to post on their public internet website the entity’s current policy governing MAiD [20]. Washington’s Senate Bill No. 5179 (SB 5179), which took effect in July 2023, requires end of life services and Death With Dignity Act policy be included in the information hospitals must post to a website location readily accessible to the public [21]. SB 5179 only applies to hospitals whereas SB 380 applies to all healthcare entities. The latter is most reflective of the nature of hospice care which can be provided in a multitude of settings including a patient's home, a free-standing or independent facility, a hospital, or a nursing home/assisted living center [22].

To date, no large-scale efforts have been undertaken to scope the issue of aid-in-dying policy availability across the United States or the effect of statutory policy transparency mandates. The aim of this article is to assesses the current public availability of aid in dying policy in all relevant jurisdictions with a focus on hospice providers. This is necessary to evaluate whether legal mandates effect the intended changes to improve policy availability and support information transparency.

Methods

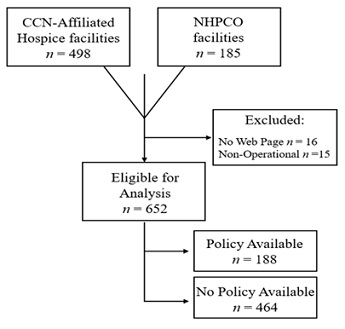

A list of hospice-providing facilities and entities was generated from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) online web directory [23]. A total of 498 facilities were identified after applying filters for the eleven applicable two letter postal abbreviations and facilities with a CMS Certification Number (CCN). The CCN is a 6-digit facility identifier used by CMS to verify that a facility has been Medicare-certified for specific services. A list of additional facilities was then queried from the from the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) web directory [24] (figure 1). Facility addresses were cross-referenced to avoid duplicates. An additional 185 facilities were identified for a total of 683 facilities.

Figure 1: Hospice policy analysis identification methods.

Figure 1: Hospice policy analysis identification methods.

Hospices were eligible for review if they: (1) were operational between May and August 2023 and (2) had an English-language web page that was (3) publicly accessible via internet search engine. 31 facilities (4.5%) did not meet inclusion criteria. Eligible web pages were then searched using the terms medical aid in dying; aid in dying; end of life option act; and death with dignity. Web pages were searched for additional legislative-specific terms in Colorado (Proposition 106); Hawaii (Our Care Our Choice Act); Montana (Baxter v. Montana); New Mexico (Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act); and Vermont (Act 39). The results are reported in Table 1.

|

|

Facilities (n) |

Non-Operational or Closed (n) |

No Web Page Identified (n) |

n Eligible for Review (%) |

n Policy Posted (%)? |

|

California |

251 |

5 |

4 |

242 (96.4) |

122 (50.4) |

|

Colorado |

91 |

3 |

3 |

85 (93.4) |

16 (18.8) |

|

DC, Washington |

3 |

– |

– |

3 (100) |

0 (0) |

|

Hawaii |

11 |

– |

– |

11 (100) |

3 (15.0) |

|

Maine |

19 |

– |

– |

19 (100) |

0 (0) |

|

Montana |

37 |

– |

– |

37 (100) |

6 (16.2) |

|

New Jersey |

78 |

2 |

5 |

71 (91.0) |

0 (0) |

|

New Mexico |

63 |

3 |

1 |

59 (93.6) |

15 (25.4) |

|

Oregon |

69 |

1 |

2 |

66 (95.6) |

6 (16.6) |

|

Vermont |

14 |

– |

– |

14 (100) |

1 (7.1) |

|

Washington |

47 |

1 |

1 |

45 (95.7) |

19 (42.2) |

|

Total |

683 |

15 |

16 |

652 (95.5) |

188 (28.8) |

Table 1: Hospice facilities and providers with a MAiD policy available via web page. Percentage calculated from the number of facilities eligible for review.

Results And Discussion

- National Data

More than 95% of facilities surveyed in this review had a web page accessible by public internet search engine. Only 188/652 (28.8%) of facilities that met review criteria had an aid-in-dying policy located on their public web page. No policies were identified for facilities in Maine, New Jersey, or Washington, DC (n=93).

- Nomenclature

Ethical health communication strategy begins with equity and ease of access to information. Policy titles must be reflective of current legal and medical lexicons as these are the terms prospective patients and their family members are most likely to employ when conducting an online search. There has been a significant shift in policy naming practices over the last decade towards a more uniform, regulatory-based lexicon. We located four policies (2.1%) whose titling terminology was not reflective of relevant legislation or of the contemporary lexicon surrounding MAiD. These titles were “Physician Aid in Dying” (n=2), “Provider-Hastened Death” (n=1), “Physician Assisted Suicide” (n=1). A 2010 review of hospice policies obtain via information requests directly from Oregon facilities found that 52.7% of policies used the term “assisted suicide” while only 24.4% referred to the legislative name Death with Dignity Act [25]. By contrast, 97.9% of the policies identified in this study used the title aid in dying, medical aid in dying, or referenced the applicable state-specific legislative name like Death with Dignity Act.

Additionally, Hawaii, New Mexico, Washington now allow osteopathic providers, advanced practice registered nurses, physician assistants to provide MAiD [26]. The continued use of physician-specific language (i.e., “physician assisted” and “physician aid”) is no longer appropriately descriptive of these processes. Addressing inequalities in access to health information requires making information directly accessible and comprehensible to the public; that information must also be truthful and non-judgmental [27]. Though it may seem innocuous, policy title phraseology, connotation, choice of language are intentional and can have significant influence over patient decision-making. The varied landscape of aid-in-dying policy nomenclature has been previously critiqued as overly emotive and not accurately descriptive of the statutes, specifically in the use of value-laden terminology used to instill moral assumptions and emotional prejudgments about a patient's decision [28]. Facility policies that have historically used stigmatizing terminological variations like “suicide” were less likely to support MAiD and more likely to be religiously affiliated with Roman Catholicism [25]. Our results affirm these prior findings as the policies that reference suicide and hasted death were operated by Catholic and Christian health care system. The continued errant analogization between MAiD and euthanasia by groups like the Catholic Health Association [29] not only stigmatizes MAiD as an illegitimate end of life care option, but violates legal provisions which prohibit health care entities from engaging in false, misleading, or deceptive practices relating to policy concerning end-of-life care services [20]. Euthanasia occurs when someone other than the patient administers medications. Euthanasia is not permitted in the US. MAiD requires a patient to self-administer the prescribed medications. The AMA and the American Nurses Association (ANA) explicitly distinguish the practice of aid in dying as distinct from euthanasia [7,30]. While health care policies can and should reflect the ethos and guiding principles of an organization, the development of these communication and policy materials must be done in a manner that is respectful and not condescending of individual patient values [31]. All four separate policies which used outdated terminology or morally culpable language in their titles were shared policies with far-reaching scopes.

- Shared Policies

The presence of shares multi-facility policies was sizeable. Within California specifically, the 122 facility web pages with a policy posted included only 41 unique policy statements or documents. This was the result of care corporations and hospital networks which operate under a singular shared policy. An average of 2.9 California facilities was covered per policy. The largest was Providence Health & Services, a Catholic health care system whose aid in dying policy covered nearly 90 facilities across 7 states. The presence of these shared policies can distort the perception that half of California facilities are compliant with the posting requirements of SB 380. When analyzed closer, 22 single-site California facilities were found to have a policy posted whereas 65 single-site California facilities did not.

We theorize that multi-facility care corporations and large hospital systems are more likely to post operational policies because these health entities have legal and regulatory departments whose job duties include monitoring compliance with statutory changes, creating uniform site policy, reviewing standard operating procedures. However, we also contend that posting a policy to a web page represents a very low bar for small group, independent, or stand-alone facilities to meet. SB 380 took effect over eighteen months ago and New Mexico’s law passed more than two years ago. This is ample time for any health care entity to have adhered to any and all requirements set forth.

- Policy Content

The primary objective of this survey review was to identify the availability of MAiD policies. Although the aim was not to analyze nor catalog policy content, it was evident that there were significant variations in policy content, clarity, thoroughness. A policy is defined as a high-level overall plan detailing the general goals and acceptable procedures [32]. The processes to access MAiD are complex and prospective patients have the right to understand how a chosen hospice provider will respond if that patient makes a request for MAiD at the end of life. Multiple policies from facilities in California, New Mexico, Vermont were no more than one sentence in length. Others made no attempt to describe any procedural processes, instead using terms like “opt out” or “neutral position.” Select examples are listed in Table 2.

|

Vague or non-specific aid-in-dying policy language |

|

“Emanate Health facilities will not participate in the End Of Life Option Act.” California “YoloCares supports patient rights and choices through offering Education and Support about the EoLOA.” California “HopeWest has chosen to opt out of participation.” Colorado

|

|

“[Brattleboro Area Hospice] BAH has maintained a neutral position which remains in place now that Act 39.” Vermont |

Table 2: Examples of vague or non-specific aid-in-dying policy language.

The use of non-specific terminology and vague language can lead to uncertainty, confusion, differing interpretations about the permitted roles of providers, facilities, patients if a request for MAiD were to be made. Additional qualitative and interview-based research is planned to further analyze of the scope and diversity of aid-in-dying policy content identified in this review.

Limitations

This research project did not aim to be exhaustive in its review of every potential health care entity that might receive a patient request for MAiD. This research focuses primarily on the intersection of MAiD with hospice/palliative care facilities and providers. The public CMS and NHPCO web directories were selected to identify health care entities within this field, the number of entities reviewed is considerably larger than previously reported single-state studies of hospice MAiD policies [25,28]. This research did not extensively cover private and group medical practices, membership-based concierge medical services, or community-based provider groups which also routinely provide hospice and palliative care.

Conclusion

This research is among the first to map the public availability of hospice policies on a large scale across every US jurisdiction where aid in dying is legal. Incomplete policy disclosure remains an area of ongoing concern and is an under-researched area of end-of-life care literature. It is not currently standard practice for hospice-providing facilities and other healthcare entities nationally to make aid in dying policies publicly available. The data in Table 1 does not suggest that the majority of health care entities have no established MAiD policy. Rather, policies are likely only available to the staff within the facility or to patients only after intake. Terminally ill patients cannot follow recommendations that they choose providers and facilities based on whether they will support their end-of-life chooses if they cannot prospectively locate MAiD policy statements or protocols [33]. Statutory requirements to post a policy –as seen in California, Washington, New Mexico – are moderately effective at increasing the public availability of policies. Compliance remains at or under 50%. Nearly all policies were easily identifiable due to improvements in the uniformity of title terminology. Legal mandates may be the necessary initial impetus to change standard practice and increase policy transparency. However, accountability sanctions or review mechanisms are also likely needed to improve widespread compliance and assure content veracity. Regardless of whether a health care entity chooses to participate in or opt out of MAiD, this information must be made prospectively available to potential patients and their families. Clear communication and empowering patients them to make informed decisions about their care are core philosophical values of hospice care [34]. A lack of health policy transparency and inaccessibility represent pressing but easily surmountable barriers to supporting informed health care decision-making at the end of life.

Disclosure and Acknowledgement

The authors have no conflicts of interest regarding the design or writing of this research. The views expressed here are those of the authors and are not necessarily a reflection of the views or policies of their employers.

Funding

This work was grant supported by the Faith Sommerfield Family Foundation, Inc., Greenwich, CT.

References

- Treem J (2023) Medical aid in dying: Ethical and practical issues. J Adv Pract Oncol 14: 207-211.

- DeWolf T, Cazeau N (2022) Medical aid in dying: An overview of care and considerations for patients with cancer. Clin J Onc Nurs 26: 621-627.

- Oregon Health Authority (2023) About the Death with Dignity Act. OHA, Oregon, USA.

- Compassion and Choices (2022) States Where Medical Aid in Dying is Authorized. Oregon, USA.

- Mroz S, Dierick, S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K (2020) Assisted dying around the world: a status question. Annals Of Palliative Medicine 10: 3540-3553.

- Kozlov E, Nowels M, Gusmano M, Habib M, Duberstein P (2022) Aggregating 23 years of data on medical aid in dying in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 70: 3040-3044.

- American Medical Association (2019) Physician-Assisted Suicide (Resolution 15-A-16 and Resolution 14-A-17). Opinion of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, Illinois, USA 244-250.

- Fuller K (2022) Death with dignity is not euthanasia. MDLinx, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Clarridge C (2021) How his twin brother’s deathbed plea was a call to action for Washington state’s insurance commissioner. The Seattle Times, Washington, USA.

- Buchbinder M (2018) Access to aid-in-dying in the United States: Shifting the debate from rights to justice. Am J Public Health 108: 754-759.

- Sharma A (2023) Most local hospices aren't transparent about their aid in dying policies. KPBS News, California, USA.

- DeRosa K (2023) Woman with terminal cancer forced to transfer from St. Paul's Hospital for assisted dying. Vancouver Sun, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- California Department of Public Health (2022) California End of Life Option Act 2021 Data Report. CDPH, California, USA 1-14.

- Oregon Health Authority (2022) Oregon Death with Dignity Act 2021 Data Summary. OHA, Oregon, USA.

- Washington State Department of Health (2022) 2021 Death with Dignity Act Report. DOH, Washington, USA.

- Hawai’i State Legislature (2018) Act 2, Session Laws of Hawaii (SLH) HB2739 H.D. 1. Hawai’i, USA.

- Maine State Legislature (2019) Laws of the State of Maine ME PL 2019, c. 271, §4 (NEW). Maine, USA.

- American Clinicians Academy on Medical Aid in Dying (2022) Recommendations for the Posting of Policies that Describe a Health Organization’s Aid-in-Dying Services, as Required by California SB380. ACAMAID, USA 1-4.

- State of New Mexico (2021) House Bill 47 “Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act.” NMSA, New Mexico, USA.

- California Health & Safety Code (2021) End of Life Option Act 443.15 [j]. HSC, California, USA.

- Washington State Legislature (2019) Access to care policies for admission, nondiscrimination, and reproductive health care – Requirement to submit, post on website, and use department-created form. WA Rev Code 70.41.520, Washington, USA.

- American Cancer Society (2019) How and where is hospice care provided and how is it paid for. Georgia, USA 1-18.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2023) Hospice - General Information. CMS, Maryland, USA.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2023) Find a Care Provider. NHPCO, Virginia, USA.

- Campbell CS, Cox JC (2010) Hospice and physician-assisted death: Collaboration, compliance, and complicity. Hast Cent Rep 40: 26-35.

- Pope TM (2023) Your End-of-Life Options. Experience 33: 12-15.

- Lee C, Rogers WA (2006) Ethics, Pandemic Planning and Communications. Monash Bioethics 25: 9-18.

- Campbell CS, Black MA (2014) Dignity, death, and dilemmas: A study of Washington hospices and physician-assisted death. J Pain Symptom Manage 47: 137-153.

- Catholic Health Association of the United States. Caring for People at the End of Life. Washington, DC, USA 1-16.

- American Nurses Association (2019) The Nurse’s Role When a Patient Requests Medical Aid in Dying. ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights, Maryland, USA 1-6.

- Guttman N, Salmon CT (2004) Guilt, fear, stigma, and knowledge gaps: ethical issues in public health communication interventions. Bioethics 18: 531-552.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2023) Policy (n). Merriam-Webster Inc, Massachusetts, USA.

- Sharp HealthCare (2023) End of Life Option Act: Frequently Asked Questions. Sharp, California, USA.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2013) Hospice Values Competency Preface. NHPCO, Virginia, USA.

Citation: Strand GR (2023) A National Survey of Hospice Aid-in-Dying Policy Availability and the Impact of Legal Mandates J Hosp Palliat Med Care 5: 020.

Copyright: © 2023 Gianna R Strand, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.