A Study of Immunization Status of Kindergarten and Elementary School Students in Lexington-Fayette County, Kentucky, 2018-2019

*Corresponding Author(s):

Okojie PWInfectious Disease Unit, Lexington-Fayette County Health Department, Lexington, Kentucky, United States

Tel:+1 (434) 209-0227,

Email:pwokojie@liberty.edu / okwestonline@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background: There has been an upsurge in the outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) and their related mortalities in the United States. These are attributable to the rising trend of vaccine delays/refusals based on beliefs and ideological preferences.

Objective: This study aimed to determine the immunization status of kindergarten and elementary school students in Lexington-Fayette County, Kentucky, 2018-2019 school year.

Methods: A cross-sectional, secondary analysis of school-based vaccination records of 7,253 participants (3,599 kindergarten and 3,654 elementary students, respectively) in Lexington-Fayette County, Kentucky, was done from January to April 2020 using Microsoft Excel and SPSS V.25. A Z test of difference in proportions was employed to show the difference in vaccination coverage between kindergarten and elementary student participants.

Results: Vaccination coverage and exemption rates for kindergarten and elementary student participants were (98%, 2%) and (98.2% 1.8%), respectively. DTap had the highest vaccination coverage (99.4%) for kindergarten students. Hepatitis A vaccine had the least vaccination coverage for both kindergarten (92.2%) and elementary students (75.1%), respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in vaccination coverage between kindergarten and elementary school students for DTap (Z, 18.90) and Polio (Z, 22.90) vaccines, respectively, above 10% (P <.00001).

Conclusion: This study showed a relatively impressive school-based vaccination outlook; it, however, revealed a 2% student population who may be vaccine-hesitant, a potential threat to public health in the community. Therefore, to attain full school-based vaccination coverage, an assessment of vaccination hesitancy and determinants of uptake of school-based vaccinations in Lexington-Fayette County is thus recommended.

Keywords

Exemption Status; Immunization; VPDs; Vaccination Coverage; Vaccine Hesitancy

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of the Smallpox vaccine by Edward Jenner in 1796 opened the floodgates for further works by scientists on the application of vaccines in infectious disease prevention [1-2-3]. These efforts culminated in the discovery of a second vaccine, against diphtheria, which was applied a century later and it would be 150 years for the Polio vaccine to be introduced [4-5].

Vaccination is one of the fundamental public health achievements of the 20th century and has remarkably decreased the prevalence of infectious disease-related mortalities across the globe [6-7-8]. Apart from clean water and sanitation, few public health measures can rival the impact of vaccines which have been widely appraised as a cost-effective public health intervention with a population-wide benefit [6-9-10-11].

The successful global eradication of Smallpox and the nearly eradicated Poliovirus is key milestone achievements attributed to vaccination efforts [6&12]. Vaccines directly induce immunity to confer protection against infections in most vaccinated individuals [1]. They indirectly provide community protection through raised herd immunity by preventing the spread of infectious diseases from person-to-person [1&13].

A cost-benefit analysis of vaccine-use revealed that for a single birth cohort approximately twenty million cases of diseases were prevented, including 40, 000 mortalities [14].Vaccination does not only save lives of children but creates a positive impact on the economy. It is estimated that nearly $70 billion in net economic benefit has been attributed to vaccination in the United States [12]. An economic evaluation of 10 vaccines in 94 low-and middle-income countries showed that an almost $34 billion investment in immunization program resulted in saving $586 in reducing costs of illness and $1.53 trillion when broader economic benefits were included in the analysis[15].

The World Health Organization has prioritized immunization which is included as a core to the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [16]. This is in keeping with the Global Vaccine Action Plan that is aimed to prevent millions of death by 2020 through enhanced global vaccine access and utilization strategies [16]. Children’s health is central to achieving the SDGs and the school system has remained a crucial avenue to the successful enforcement of state or local immunization mandates to achieve this major global development milestone. However, the role of parents in immunization cannot be overlooked as they make early life decisions for their children who are of schooling age including acceptance or refusing them the right to get immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases.

Following the Supreme Court ruling of 1922 upholding the constitutionality of vaccinations, mandatory school vaccination programs and vaccination requirements have existed in the United States for nearly a century [17]. These school vaccination requirements vary by state and local authorities and are aimed to protect school children from vaccine-preventable diseases [18].

Despite the plethora of scientific evidence of the positive health and social impacts of vaccination on children and society at large [6-10-11-16]school vaccination has been met with stiff resistance from figures in the society, whose towering influence has continued to gain huge support and followership among some parents, many of whom now hesitate, delay or at rightly refuse vaccination for their children [19].

The recent upsurge in the outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases and their related mortalities in the United States have been attributed to this rising trend of vaccine delays or their complete refusals based on non-medical exemptions, mostly rooted in personal beliefs and individual ideological preferences[20-21-22]. It is estimated that an alarming 2.0% of parents decline all forms of vaccinations for personal reasons. Published data shows that from 2004 to 2011, the mean rate of non-medical exemption per state in the U.S. increased from 1.5% to 2.2% [23]. According to the CDC’s report for the 2018-2019 school years, the U.S. national estimate of vaccination exemption rate for children in kindergarten stood at 2.5% showing a 0.5% increase from the 2017-2018 school year report [24].

In the 2017-2018 school year, the CDC reported national vaccination rates for MMR (94.3%), DTap-4 or 5 doses, (95.1%), Varicella-2 doses (93.8%) among children in kindergarten [25]. The corresponding coverage rates for these vaccines in the State of Kentucky were 92.6%, 93.7%, and 91.7%, respectively.25 These relatively high estimates, unfortunately, may conceal clusters of under-vaccinated children[18] .The proportion of vaccine refusals have been shown to be associated with an increase in the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases in recent times[26]. The findings of this study could potentially reveal immunization prevalence gaps in kindergarten and elementary school students in Lexington-Fayette County. This will serve the purposes of planning and prioritization of the allocation of resources for the implementation of initiatives aimed at promoting vaccine acceptance and increase uptake within the Lexington-Fayette County area. Furthermore, they could spark research into the determinants of vaccine hesitancy, especially among parents of school aged children who make critical vaccination decisions on behalf of their kindergarten and elementary school children in the county. Hence this study aimed to determine the immunization status of kindergarten and elementary school students in Lexington-Fayette County, Kentucky.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study used a cross-sectional design to analyze secondary data of kindergarten and elementary school immunization records for 2018-2019 academic years, Lexington-Fayette County, Kentucky. A population sample of 7,253 (kindergarten, 3,599 and elementary 3654, respectively) was selected using available records obtained from the State Immunization Registry between January and April 2020. A secondary data collection instruments was used to obtain data on vaccination and exemption status of kindergarten and elementary school students. Confidentiality was ensured by de- identifying individual student/school record during data entry with the use of serial coding only. Furthermore, all data acquired through this study were kept in password-protected computer files within the Lexington-Fayette County Health Department. School-based vaccination data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel Real Statistics software and SPSS [25]. Tables and charts were used to present the immunization and exemption rates in kindergarten and elementary school students. A test of difference of proportions was done to show the difference in vaccination rates between kindergarten and elementary student participants. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 3,599 kindergartens and 3,654 elementary school student’s vaccination records were analyzed during this study (Table 1).

|

Status |

|

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

Kindergarten students Medical exemption |

|

(n=3599) 12 |

0.33 |

|

Religious exemption |

|

60 |

1.67 |

|

Vaccinations |

|

3,527 |

98.0 |

|

Elementary students Medical exemption Religious exemption Vaccination |

|

(n=3654) 25 41 3588

|

0.68 1.12 98.2 |

Table 1. Vaccination/exemption status of kindergarten and elementary school students, Lexington-Fayette County, 2018-2019 school year

Ninety-eight percent of kindergarten students in Lexington-Fayette County were vaccinated in the 2018-2019 school year. Of the 2% of kindergarten students with vaccination exemption, 1.67% were no- medical (religious exemption) while 0.33% were medical exemptions. Ninety-eight percent of elementary school students in Lexington-Fayette County were vaccinated in the 2018-2019 school year. Of the 1.8% of elementary students with vaccination exemption, 1.12% were non-medical (religious exemption) while 0.68 % were medical exemptions.

Vaccination coverage rates for specific vaccines administered to kindergarten students in Fayette County in the 2018-2019 school years were: Dtap, 99.4%; Polio, 99.5%; HepB, 99.2%; MMR, 97.9%; Varicella, 97.4%; HepA. 92.2%. Dtap had the highest vaccination coverage. The least Hepatitis A had the least vaccination coverage. Vaccination coverage rates for specific vaccines administered to elementary school students in Fayette County in the 2018-2019 school years were: Dtap, 89.0%; Polio, 85.1%; HepB, 97.6%; MMR, 97.3%; Varicella, 95.4%; HepA. 75.1% (Table 2).

|

Vaccine |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

Kindergarten students |

(n=3599) |

|

|

DTaP |

3,572 |

99.4 |

|

Polio |

3,583 |

99.5 |

|

HepB |

3,571 |

99.2 |

|

MMR |

3,526 |

97.9 |

|

Varicella |

3,506 |

97.4 |

|

HepA |

3,317 |

92.2 |

|

Elementary students |

(n=3654) |

|

|

Dtap |

3,253 |

89 |

|

Polio |

3,111 |

85.1 |

|

HepB |

3,565 |

97.6 |

|

MMR |

3,554 |

97.3 |

|

Varicella |

3,485 |

95.4 |

|

Hep A |

2,745 |

75.1 |

Table 2. Vaccination coverage among kindergarten students in Lexington-Fayette County, 2018-2019 school year

There was a comparable proportion of vaccination coverage between kindergarten and elementary school student participants with a slight percentage difference between them; MMR (97.9%, 97.3%), HepB (99.2%, 97.6%), and Varicella (97.4%, 95.1%), respectively (Table 3). The difference in vaccination coverage between kindergarten and elementary school students for Dtap and Polio vaccines was more than 10%. Vaccination coverage was found to be least for Hepatitis A when compared to other vaccines in both the student population. Overall, there was no statistically significant difference in the vaccination coverage rate for MMR vaccine between kindergarten and elementary student population.

|

Vaccination |

|

Coverage Rates Kindergarten (%) Elementary (%) |

|

Z |

P |

||

|

DtaP |

|

99.4 |

|

89.0 |

|

18.90 |

<.00001 |

|

Polio |

|

99.5 |

|

85.1 |

|

22.90 |

<.00001 |

|

Hep B* |

|

99.2 |

|

97.6 |

|

5.41 |

<.00001 |

|

MMR |

|

97.9 |

|

97.3 |

|

1.67 |

.09492 |

|

Varicella |

|

97.4 |

|

95.4 |

|

4.57 |

<.00001 |

|

HepA* |

|

92.2 |

|

75.1 |

|

19.66 |

<.00001 |

Narration, *HepA=Hepatitis A, HepB*=Hepatitis B

Table 3. Result of the test of difference in the proportion of vaccination coverage between kindergarten and elementary student population, Lexington-Fayette County, 2018-2019 school year.

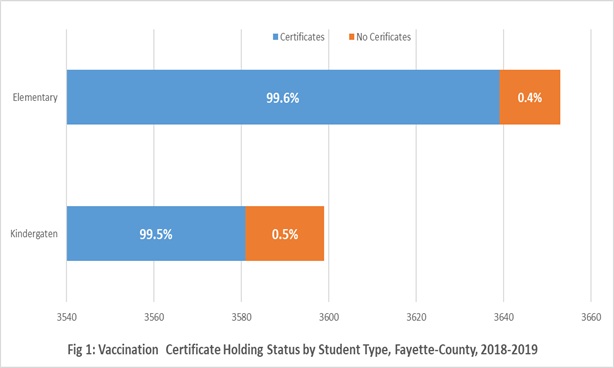

A major proportion of the study participants (kindergarten, 99.5%; elementary 99.6%) had vaccination certificates. Only 0.5% of kindergarten students had no vaccination certificates while 0.4% of elementary students had no vaccination certificates (Fig 1).

DISCUSSION

The data highlights the coverage rates for specific vaccines required for maintaining school enrollment. This requirement is not unique to Lexington-Fayette County alone, as mandatory student vaccination is practiced throughout the state of Kentucky [27-28]. Vaccination requirement for school enrollment has been a practice in the United States for nearly a century, and the continuation of this practice despite opposition over the years has been predicated on sound scientific evidence of the potency of vaccines to protect children from infectious disease by boosting the immune system directly, and the indirect protection from herd immunity it provides for the larger population [1-13-19]. Also, the data on vaccination exemption status of the student population points to the fact that despite an almost century-long practice of vaccination of school children, a section of unvaccinated people in the population may pose a threat to public health[29]. This study showed ninety-eight percent of kindergarten students in Fayette County were vaccinated in the 2018-2019 school year. This proportion exceeded the U.S average for MMR, pertussis, varicella, respectively for the same school year [30]. Of the 2% of kindergarten students with vaccination exemption, 1.67% was religious exemptions while 0.33% was medical exemptions.

According to the data, the overall vaccination rate for kindergarten school children in Fayette County was 98%, leaving a 2% prevalence gap in the unvaccinated kindergarten population. This was comparable to the vaccination coverage rate of the elementary school student population in the county as well. Although the data showed a 2% proportion of vaccination exemption status in either kindergarten or elementary schools, however, they also appeared to suggest that religious exemption rather than medical exemptions accounted more for the observed number of unvaccinated kindergarten and elementary school student population, respectively. This finding is consistent with that of a systematic review of school immunization requirement which showed evidence of rising rates of nonmedical exemptions (NMEs) from school-entry vaccine mandate [31]. As children do not make vaccination-based decisions, it could be hypothesized that this trend may be attributed to the role of vaccine-hesitant parents or vaccine refusers [32]. This hypothesis is consistent with past research which documented that an alarming 2% of parents decline all forms of vaccinations for personal reasons [23]. Besides, the 2% vaccination exemption rate observed in this study is also consistent with published data which showed that from 2004 to 2011, the mean rate of non-medical exemption per state in the U.S. increased from 1.5% to 2.2%.23 Furthermore, this study showed a 0.5% lower vaccination exemption rate compared with the published CDC’s U.S. national vaccination exemption rates report for the 2018-2019 school year, for children in kindergarten which stood at 2.5% showing a 0.5% increase from the 2017-2018 school year report[24].

According to the data, the overall vaccination rate for kindergarten school children in Fayette County was 98%, leaving a 2% prevalence gap in the unvaccinated kindergarten population. This was comparable to the vaccination coverage rate of the elementary school student population in the county as well. Although the data showed a 2% proportion of vaccination exemption status in either kindergarten or elementary schools, however, they also appeared to suggest that religious exemption rather than medical exemptions accounted more for the observed number of unvaccinated kindergarten and elementary school student population, respectively. This finding is consistent with that of a systematic review of school immunization requirement which showed evidence of rising rates of nonmedical exemptions (NMEs) from school-entry vaccine mandate [31]. As children do not make vaccination-based decisions, it could be hypothesized that this trend may be attributed to the role of vaccine-hesitant parents or vaccine refusers [32]. This hypothesis is consistent with past research which documented that an alarming 2% of parents decline all forms of vaccinations for personal reasons [23]. Besides, the 2% vaccination exemption rate observed in this study is also consistent with published data which showed that from 2004 to 2011, the mean rate of non-medical exemption per state in the U.S. increased from 1.5% to 2.2%.23 Furthermore, this study showed a 0.5% lower vaccination exemption rate compared with the published CDC’s U.S. national vaccination exemption rates report for the 2018-2019 school year, for children in kindergarten which stood at 2.5% showing a 0.5% increase from the 2017-2018 school year report[24].

Vaccination coverage rates for specific vaccines administered to kindergarten students in Fayette County in the 2018-2019 school years suggested that Hepatitis A was the least, 92.2% compared to the other recommended vaccines. This trend was also observed in the elementary students who had a Hep A vaccination rate of 75.1%. These statistics may reflect the current rate of compliance with the new Kentucky mandate on Hepatitis A vaccination for children, as a requirement for school enrollment for children. The state of Kentucky commenced the implementation of a new immunization mandate in 2018; a 2-Dose series of hepatitis A vaccine for children 12 months through 18 years [33]. In this study, the HepA vaccination coverage for kindergarten students was 17% higher than that of elementary school students. Being a relatively new state vaccination mandate, it may be argued that a one-year post-implementation assessment may be too early to substantially reflect the uptake of the HepA vaccine in the population. According to a published national progress report on Hepatitis A, there has been an observed increase in the proportion of children aged 19 to 35 months who receive more than two doses of Hepatitis A vaccine from 19% in 2010 to 85% in 2020[34].

In this study, the analysis of the test of difference in the proportion of vaccination coverage between kindergarten and elementary student population showed a statistically significant difference between vaccination coverage’s for Dtap, Polio, HepB, Varicella, and HepA, respectively. This may imply that there are a universally high vaccination rate and acceptance of these vaccines. Previously published data shows that vaccination rates are relatively high [28]. Generally, it may appear there is a relatively high vaccination coverage rate among the study population. While this trend remains, there is a need to sustain the pace and work for improved school vaccination program, as any complacency may erode the present gains. Furthermore, the relatively high vaccination rates seemed to be more consistent among the kindergarten compared to the elementary student population. The 2% unvaccinated student population could pose a public health risk and may be linked to potential future outbreaks. An outbreak of measles or pertussis in a school with unvaccinated student population will put students at risk of contracting the disease with a possibility of transmission to the community if adequate protective measures are not taken [26].

The data showed a slightly lower vaccination rate among the elementary school population. This may open an opportunity for vaccination program operations research to explore factors responsible for the observed trend and recommend ways for improvement. Such an initiative may help in closing the gap in kindergarten-elementary vaccination rates in the county through scale up efforts.

The Hepatitis A vaccination coverage rates in this study can be described as less than impressive. It may be too early to have sufficient data that accurately reflects the uptake of this vaccine in the population considering that its implementation was approved in 2018[33].Perhaps a five-year post-implementation assessment will yield more data and allow for a more robust assessment of Hepatitis A vaccine uptake in the study population. Consequently, the Fayette County Public Health Administrators and Planers can engage the health educators to implement strategies for enhancing the diffusion of the relative innovation in the continuum of vaccines required for school children in Kentucky.

This study showed a relatively impressive school-based vaccination outlook; it however, revealed a 2% student population who may be vaccine hesitant, a potential threat to public health in the community. Therefore, to attain full school-based vaccination coverage, an assessment of vaccination hesitancy and determinants of uptake of school-based vaccinations in Lexington-Fayette County is thus recommended.

REFERENCES

- Riedel S (2005) Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 18: 21–25.

- Smith KA (2011) Edward Jenner and the smallpox vaccine. Front Immunol 2:21.

- Kumar P, Sharma P (2019) Role of vaccines on human health-A review. SSR Inst. Int. J. Life. Sci. 5: 2122-2125.

- Diekema DS (2014) Personal belief exemptions from school vaccination requirements. Annu Rev Public Health 35:275–292.

- Hussein HI, Chams N, Chams S, Sayegh SE, Badran R et al (2015) Vaccines Through Centuries: Major Cornerstones of Global Health. Front Public Health 3:269.

- Greenwood B (2014) The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present, and future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369(1645):20130433.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: changes in the public health system. JAMA 283:735–738.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten great public health achievements - 2001- 2011. MMWR 60: 619-623.

- Plotkin SL, Plotkin SA (2004) A short history of vaccination. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, eds. Vaccines, 4th Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1-15.

- Bruhn CA, Hetterich S, Schuck-Paim C, Kurum E, Taylor RJ, et al (2017) Estimating the population-level impact of vaccines using synthetic controls. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114 :1524–1529.

- Andre FE, Booy R, Clemens J, Datta SK, John TJ, et al (2020) Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death, and inequality worldwide. Bulletin of the World Health Organization.

- Orenstein WA Ahmed R (2017) Simply put: Vaccination saves lives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:4031- 4033.

- Kim TH, Johnstone J, Loeb M (2011) Vaccine herd effect. Scand J Infect Dis 43: 683–689.

- Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, Messonnier, Wang LY, et al (2014) Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009.Pediatrics 133:577–585.

- Ozawa S, Clark S, Portnoy A, Grewal S, Brenzel L, et al (2016) Return on investment from childhood immunization in low- and middle-income countries, 2011-20. Health Aff (Millwood) 35:199–207.

- World Health Organization. Immunization agenda 2030;A global strategy to leave no one behind

- Salmon DA, Teret SP, Macintyre CR, Salisbury D, Burgess MA (2006)Compulsory vaccination and conscientious or philosophical exemptions: past, present, and future.Lancet 367:436-442.

- Omer SB, Salmon DA, Orenstein WA, deHart MP, Halsey N (2009) Vaccine refusal, mandatory immunization, and the risks of vaccine-preventable diseases. N Engl J Med 360:1981–1998.

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R et al (2013) Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 9:1763–1773.

- Jariyapitaksakul C, Tannirandorn Y (2013) The occurrence of small for gestational age infants and perinatal and maternal outcomes in normal and poor maternal weight gain singleton pregnancies. J Med Assoc Thai 96:259-265.

- Committee National Vaccine Advisory. Assessing the State of Vaccine Confidence in the United States: Recommendation from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Public Health Reports 130: 573-595.

- Callender D (2016) Vaccine hesitancy: More than a movement. Hum Vaccin Immunother 12: 2464–2468.

- Omer SB, Richards JL, Ward M, Bednarczyk RA (2012) Vaccination policies and rates of exemption from immunization 2005-2011. N Engl J Med 367 :1170-1171.

- Seither R, Loretan C, Driver K, Mellerson JL, Knighton CL, et al (2019) Vaccination and exemption rates among children in kindergarten-United States, 2018-2019 school year. Morb Mort Wkly Rep 68; 905-912.

- Mellerson JL, Maxwell CB, Knighton CL, Kriss JL, Seither R et al (2018) Vaccination coverage for selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten-United States, 2017-2018 School year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67: 1115-1122.

- Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer SB (2016) Association between Vaccine Refusal and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States: A Review of Measles and Pertussis. JAMA 315:1149–1158.

- Kentucky cabinet for health and family services. Recommended immunizations.

- Seither R, Masalovich S, Knighton CL, et al (2014) Vaccination coverage among children in kindergarten - United States, 2013-14 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:913-920.

- Ventola CL (2016) Immunization in the United States: Recommendations, Barriers, and Measures to Improve Compliance: Part 1: Childhood Vaccinations. P T 41:426-436.

- Seith R, Loretan C, Driver K, Mellerson JL, Knighton CL et al (2019) Vaccination coverage with selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten-United States, 2018-2018 School Year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:905-912.

- Wang E, Clymer J, Davis-Hayes C, Buttenheim A (2014) Nonmedical exemptions from school immunization requirements: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 104: e62-e84.

- Facciolà A, Visalli G, Orlando A, et al. (2019) Vaccine hesitancy: An overview on parents' opinions about vaccination and possible reasons of vaccine refusal. J Public Health Res 8:1436.

- Kentucky annual school immunization survey report for school year 2018-2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Viral Hepatitis. National Progress Report 2020 Goal.

Citation: Okojie PW, Graf LM, Hollie S, Mia W, Moon J (2020) A Study of Immunization Status of Kindergarten and Elementary School Students in Lexington-Fayette County, Kentucky, 2018-2019. J Vaccines Res Vaccine, 6: 016.

Copyright: © 2020 Okojie PW, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.