Approach to End-of-Life Care in Patients with Neuromuscular Disorders Utilizing Mechanical Ventilatory Support

*Corresponding Author(s):

Joseph BarneyDivision Of Pulmonary And Critical Care Medicine, Department Of Medicine, University Of Alabama At Birmingham, United States

Email:jbarney@uabmc.edu

Abstract

Patients with progressive neuromuscular disorders represent a small portion of patients with chronic disease in adults and children, but disproportionately utilize health care services and care giver assistance. Advances in medical care and technology have increased life spans in many of these patient populations and improved quality of life, however, they create new challenges in navigating caregiver fatigue, encounters with general medical staff at times of acute illness, and end of life care. One of the most significant advances in the medical care of neuromuscular disease patients arose from the ability to provide ventilatory support when their natural neuromuscular apparatus reaches an inflection point of insufficiency.

Patients supported by invasive or noninvasive ventilation at home or in ambulatory settings often have varying perceptions on life expectancy, quality of life, burdens on care givers, and how they will ultimately die given their adaptation to and dependence on mechanical devices to survive. We discuss several components of end-of-life care in this unique patient population and an approach to creating a framework for longitudinal care that incorporates ongoing ventilatory support with pragmatic guidance to patients and care givers on death and dying.

Background

Neuromuscular disorders that lead to substantial impairment in respiration have high mortality rates and create unique environments of morbidity and anxiety for patients. The introduction of negative pressure respiration devices dates to as early as 1864 by Dalziel, but the archetype of mechanical ventilation use in neuromuscular diseases arose with the use of ventilators in supporting polio victims during the pandemic of the mid-20th century. Ibsen introduced positive pressure techniques by tracheostomy and positive pressure ventilation in polio patients, substantially reducing mortality in thousands of infected individuals. Logistically this posed new challenges, given the lack of effective ventilation devices, and required manual respiration by staff with bag devices continuously. Subsequent technology moved to negative pressure ventilation techniques and a new population of polio patients chronically living with immobility and dependence on iron lung ventilators to survive emerged. Many patients with with acute polio syndrome utilized negative pressure ventilation with this technique only briefly and regained enough neuromuscular strength to breathe independently, but the paradigm of a population of patients living with the ongoing support of mechanized respiration until death was created out of this epidemic [1-3].

Advances in technology have made home ventilation substantially more prevalent related to some key factors such as increased portability and smaller size of equipment, longer battery life, and more sophisticated monitoring devices. The global market for portable ventilators in 2024 has been valued at 1.2 billion dollars with projections for an increased annual growth rate of 6 percent. North America accounts for 45 percent of this expenditure and use of home ventilation devices, driven by higher rates of chronic respiratory diseases and its health care infrastructure. A major contribution to this growth relates to an aging population with more diseases such as COPD that now utilize non-invasive ventilation support at advanced stages. Models of home ventilators now weigh under six pounds, have integrated carbon dioxide monitoring systems and features such as auto adjust that incorporate patient airway pressure in real time to modulate subsequent driving pressure from the device. Where patients once laid in negative pressure tank devices and navigated how to get adequate rotation to prevent pressure ulcerations, they and their caregivers now deal with how to get ventilator equipment through airport security for travel.

The scope and impact of emergency room care and hospitalizations on patients with diseases that are supported by ambulatory ventilation is difficult to encompass due to the vast amount of disease heterogeneity. In children with tracheostomies, for example, tube feeding and chronic mechanical ventilation, are independent risk factors for emergency room visits and readmissions after placement of tracheostomy occurs. Pediatric patients with tracheostomies have substantially higher rates of pulmonary infections than their adult counterparts. Diseases with neurological impairment, chronic mechanical ventilation, and gastrostomy tube dependence carry some of the highest rates of admissions for pediatric patients, and are all independent risk factors for encountering emergency room care [4,5]. Similarly, adults with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) have much higher health care utilization and costs as their disease progresses to more advanced stages, usually when the incorporation of mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy are brought into daily medical care for individuals and their families [6]. In this population, emergency room visits and admissions related to respiratory failure and pneumonia have high correlative value with mortality [7]. Efforts to prevent events, such as aspiration of gastric feeds, can make meaningful reductions in mortality, but health care providers can also utilize major events such as these to introduce dialogue with patients and their surrogates on longitudinal care goals and palliative care.

Providing end of life care for complex patients supported by mechanical ventilation in the ambulatory setting presents unique challenges to providers at several segments of the health care system. Pediatric patients with advanced neuromuscular diseases or complex neurocognitive impairments such as cerebral palsy often begin living with tracheostomies and home ventilation in a system designed for children’s health care and age out into adult health care systems without clear pathways to comprehensive care. Adult patients embarking on tracheostomy and home mechanical ventilation face potential challenges with loss of speech and swallowing function, and the need for intensive caregiver support and training. While the vast heterogeneity of patients with ambulatory mechanical ventilation may make discussions in end-of-life care daunting for health care providers to initiate, we outline an approach utilizing fundamental and generalizable aspects of their care that can be applied in a comprehensive and collaborative way. Specifically, we focus on aspects of life expectancy perceptions and mortality milestones, caregiver dynamics, and quality of life metrics in a model that can be applied to patients living with chronic mechanical ventilation support regardless of their age cohort and diagnosis.

Life Expectancy Perceptions

How long a patient will live with any disease is a determination made based on imprecise data at best and applies this from larger cohorts to an individual subject. The earliest attempts at this came in the form of actuarial tables, which sought to predict life expectancy of an individual from their current age. These formulas were based on statistical analysis of cohort data, individual demographic information, and health risk behaviors and remain widely used in the commercial rating and cost of life insurance products. This approach is limited by lack of customizable information in data sets for most chronic medical conditions and does not consider the impact of medical support devices, advances in medical therapies for chronic diseases, and technology that allows for earlier detection of disease. It is axiomatic that the tools available for medical providers to predict life expectancy for patients with complex chronic illnesses are sparse and not bespoke for any specific illness, especially patients with neuromuscular diseases living with mechanical ventilation support.

Adult patients with motor neuron diseases saw significant increases in prevalence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYS) from 1990 to 2017. That, coupled with the fact that adults with motor neuron disease saw age adjusted mortality rates rise more than any other major neurological disease in this time frame reflects the weight and importance of creating a framework for navigating progression of disease with these patients after diagnosis [8-13].

Systematic reviews of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (DMD) demonstrate trends in increasing median life expectancy from 25.8 years in cohorts born between 1955-1969 to 40.9 years in patients born after 1970 due mainly to access to tracheostomy and ambulatory ventilation support. Prospective studies of ALS clearly show longer life expectancy in patients with tracheo-invasive ventilation compared to non-ventilated and non-invasive ventilated patients by as much as 48 months. Patients with bulbar onset ALS tended to be overrepresented in these cohorts when tracheo-invasive ventilation was undertaken directly rather than transitioning from non-invasive ventilation to tracheo-invasive ventilation [14-20]. Progressive neuromuscular or neurologic disorders that involve loss of effective mechanical respiration are a heterogenous group with homogenous characteristics and likely all have expanded life expectancy with outpatient mechanical ventilation. They are characterized based on increased life expectancy with ventilation, median increase in survival, and evidence supporting this in table 1 [21-27].

|

Disease |

Reduced mortality with mechanical ventilation |

Median increase in life |

Evidence Based data |

|

Amyotrophic Lateral sclerosis |

Yes |

4 years |

Yes |

|

Duchenne’s Muscular Dytrophy |

Yes |

10-14 years |

Yes

|

|

Limb-Girdle muscular dystrophy |

Yes |

Unknown |

No |

|

Becker muscular dystrophy |

Yes |

Unknown |

No |

|

Myotonic Dystrophy |

Yes |

Unknown |

No |

|

Emery-Dreifuss |

Unknown/Unlikely |

unknown |

No |

Table 1: Impact of Mechanical Ventilation on mortality in neuromuscular diseases

When engaging in dialogue with patients with neuromuscular disease and their caregivers we outline four major areas of patient functionality whose loss correlates with increased morbidity and at some point mortality for patients. These milestones to mortality are loss of ambulation, inability to breathe without assistive devices, dysphagia requiring percutaneous nutrition, and cognitive decline.

The loss of axial muscle strength that leads to inability to stand and ambulate in neuromuscular diseases is one of the earliest and most devastating changes for patients and caregivers alike. Not only must the patient adapt to a world that has to move around them more than individually moving through it, but their home environment, transportation, and caregiver commitment to in person care undergo radical shifts with long term effects. Psychologically this leads to depression and anxiety in patients who often are cognitively unimpaired but physically incarcerated by their disease.

Immobility has been shown to precede depression in several studies of general patient populations who experienced acute loss of ambulation. An analysis of adults with muscular dystrophy, spinal cord injury, and multiple sclerosis has demonstrated lower mobility correlates with higher depression scores, reflecting the generalizable effect loss of ambulation has on mental health [28,29]. Several studies have shown higher rates of suicide among patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis over general populations, but correlating the impact of loss of mobility on this outcome have not been able to be quantified retrospectively [30,31]. The relationship between loss of ambulation with onset of mortality in heterogeneous groups of patients with neuromuscular diseases have not been assessed in aggregate. Studies of patients with myotonic dystrophy, which tends to have a delayed onset and longer survival, show correlations between the loss of ambulation and onset of death relatively soon thereafter [32].

Data on impaired mobility with time to mortality in patients with ALS are sparse, but prospective studies on the timed up and go test (TUG) in this disease did not show a direct correlation between loss of ambulation and death. The TUG is a standardized instrument to measure ambulation in ALS patients. Interestingly, this cohort included bulbar ALS patients who had much higher TUG scores due to preserved peripheral strength but earlier death due to the natural progression of this form of ALS, likely confounding the results. The onset of immobility and time to death in patients with Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy are distinctly affected by treatment with long term corticosteroids, long considered standard of care in reducing muscle inflammation and loss of function. Long term steroid use delayed loss of muscle function and preserved mobility compared to minimal or non-steroidal treated male subjects and delayed onset of mortality [33].

In large analyses of in hospital hypercapnic respiratory failure neuromuscular diseases have substantially higher mortality compared to patients with advanced COPD and congestive heart failure. Loss of independent respiration without mechanical support devices often begins with noninvasive ventilation and only for portions of a 24-hour cycle in most neuromuscular diseases with variable progression to continuous support and elective invasive tracheoventilation techniques. With the exception of bulbar ALS, most neuromuscular disease patients do not move from spontaneous respiration to tracheostomy placement and mechanical ventilation without a variable period of noninvasive support. Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy patients have been observed longitudinally to have substantial morbidity from both respiratory related illness and cardiovascular complications. In patients electing to not transition from non-invasive ventilation support to tracheoinvasive ventilation, most succumb to hypercapnic respiratory failure before cardiomyopathy complications become terminal. Ubiquitously any patient with a neuromuscular disorder who is making decisions about embarking on tracheostomy and invasive ventilatory support can expect that choosing a route of remaining unencumbered by this support system comes at a cost of much sooner mortality [34,35].

Emergence of dysphagia for enteral nutrition is variable among neuromuscular diseases, with later progressing forms such as Emery Dreyfuss Muscular dystrophy having very little impairment in swallowing for most of the natural course of life. ALS uniquely bifurcates into bulbar forms with very early inability to manage oral secretions and aspiration of oral nutrition and nonbulbar ALS with loss of peripheral muscle strength and ambulation which precedes the eventual loss of swallowing function. Regardless of the time of introduction of parenteral feeding tubes, the placement and initiation of gastrostomy tubes herald new challenges and often is associated with increased encounters with health care. Studies have shown that ALS patients electing to undergo percutaneous enteral gastrostomy tube (PEG) placement are affected by interactions between the patient, their caregivers, and the health care providers providing information and guidance on benefits and risks of changing from oral nutrition. While many thematic aspects of independence and autonomy are present in ALS patients' decision-making approach, the progression of disease imposed a necessary intervention to continue living, including PEG placement [36]. Prospective interventional research on PEG tubes demonstrated increased one year survival in patients with ALS with the caveat that this effect was seen when placement was done before patients lost more than ten percent of their prediagnosis body weight. Timing of PEG tube insertion therefore plays a major role in their effect on many aspects of survival with delayed interventions having impact on mortality and possibly increased rates of aspiration events [37,38].

Major advances in gene analysis have changed the way ALS is perceived, from an isolated disorder at the neuromotor level to a multisystem disease. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) occurs with high frequency among ALS patients who survive long enough to manifest signs prior to loss of communication and facial muscle strength. Previously thought to be two separate processes, transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) now is understood to be present in both ALS and FTD as well as repeat-containing RNA playing a role in the development of both disorders. FTD diagnosis in patients with existing ALS conveys a substantially poor prognosis and studies have demonstrated elevated levels of neurofilament light in the cerebrospinal fluid of both FTD and ALS patients. Neurfilament light is a protein expressed by large caliber axons with functions in the cytoskeleton of the central nervous system and higher concentrations in spinal fluid of ALS and FTD patients correlates directly with mortality. FTD has been reported in cases of oculopharnygeal muscular dystrophy, further linking this neurodegenerative condition with neuromuscular diseases [39]. Subtypes of myotonic dystrophies are also now linked to cerebral atrophy and FTD [40]. The presence of FTD or other forms of cognitive decline add substantial morbidity and correlate with mortality in the longitudinal progression of neuromuscular diseases (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cumulative effects on mortality in neuromuscular disease.

Figure 1: Cumulative effects on mortality in neuromuscular disease.

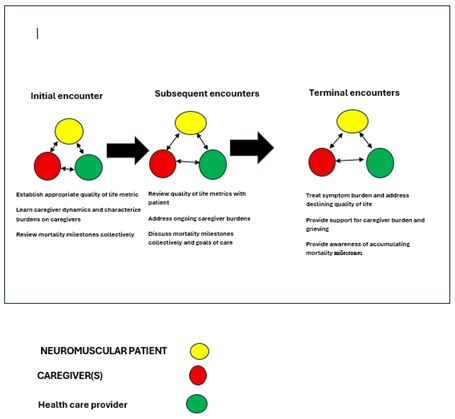

The interactions of loss of ambulation, ineffective natural respiration, dysphagia with delayed PEG nutrition, and cognitive impairments can be viewed as a linear progression with additive effects on mortality in this heterogeneous patient cohort. While some patients progress to mechanical ventilatory support and PEG based nutrition simultaneously the cumulative effects of these inflection points are additive in the larger sense of mortality (Figure 2). While having any one of these impairments does not accurately predict time to mortality in patients with neuromuscular disorders, having more of them has a synergistic effect on morbidity and subsequently mortality. In practical palliative care discussions with patients and caregivers, a patient living with neuromuscular disease who can’t walk, breathe independently, consume nutrition by oral routes, and is severely cognitively impaired is closer to a comorbid event leading to death than patients who have not accumulated all of these milestones. Rather than attempting an imprecise answer about how long any patient with these disorders will live, this reframes conversations into discussions about where patients are in relationship to impairments that make mortality more probable.

Figure 2: Comprehensive Longitudinal model of care.

Figure 2: Comprehensive Longitudinal model of care.

Caregiver Dynamics

With rare exception, neuromuscular patients supported by mechanical ventilation have deeply invested caregivers whose lives are transformed by the progression of their disease. Pediatric diseases that lead to noninvasive or tracheoinvasive ventilation support at home often involve parental decision making on proceeding to PEG placement and nutritional support, embarking on tracheostomy placement and home ventilation, and overall goals of care for children who cannot make complex medical decisions for themselves. Adults with neuromuscular disorders that manifest later in life may participate in their medical decision making directly but decisions on ambulatory mechanical ventilation and PEG nutritional support are often made with spousal or familial input. The dynamics of caregiver relationships heavily influence directions in medical care in this unique patient population [41,42].

Parental caregivers of children with neuromuscular disorders often have vastly different quality of life compared to their children with the disease and they often have to navigate the costs of providing care with their available resources [43,44]. Early pediatric diseases that lead to intensive PEG feedings and home tracheoinvasive ventilation, such as Pompe disease lead to high levels of burden of care on parents and they describe their lives as exhausting and totally involved in survey data. Patient cohorts such as Pompe disease, Duchenne Muscular dystrophy, ALS, and other rare neuromuscular disorders have caregivers that become highly educated on the disease, complications, and current medical therapies. This leads at times to parents and spouses of patients having a higher level of knowledge than many health care professionals and a phenomenon of the reversed patient-professional role that can make discussions of end of life care less productive when a neuromuscular disease is progressing closer to finality. Many family members of children with progressive neuromuscular disorders experience significant societal withdrawal and depressive symptoms, even reporting suicidal thoughts in some surveys [45]. Congruent across all pediatric neuromuscular disorders where children will be supported for long periods of time with tracheoinvasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation is a dual state of development and deterioration. For example, children with spinal muscle atrophy may embark on tracheoinvasive ventilation support and experience progressive decline in muscle strength and function and puberty simultaneously [46].

Caregivers of patients with neuromuscular diseases supported by ambulatory mechanical ventilation or approaching this inflection point are vulnerable to depression, societal withdrawal, enmeshment in their relationships and burnout. Taking into account dynamics in a family unit and caregiver understanding of their loved one’s progressive disease is fundamental to establishing dialogue on expectations and timelines as patients appear to be closer to death by objective changes in overall functioning. Pragmatically an approach that builds rapport and mutual understanding of a patient and their caregiver’s dynamics is strengthened by asking information from caregivers that allows them to provide their unique perspective on knowledge of the disease they keep at bay, their own challenges in mental health, and how they view their loved one’s experience.

Quality of Life Metrics

Disease-specific quality of life (QoL) scales are essential tools in the assessment and management of neuromuscular disorders, as they capture the unique physical, emotional, and social challenges faced by these patient populations and allow for assessment of response to treatment. Instruments such as the Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Quality of Life (DMD-QoL) and the Individualized Neuromuscular Quality of Life questionnaire (INQoL) have been developed to address the specific needs and experiences of individuals with conditions like Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies, myotonic dystrophy, and other neuromuscular diseases. The DMD-QoL is tailored to the lived experience of DMD across the lifespan, while the INQoL covers a broad range of neuromuscular disorders and assesses domains such as weakness, fatigue, pain, myotonia, breathlessness, and the psychosocial impact of disease for adult patients. For ALS, the ALS Assessment Questionnaire (ALSAQ-40/5) is widely used, focusing on domains most affected by ALS progression, including mobility, communication, and emotional well-being. In contrast, generic instruments like the WHOQOL-BREF provide a broader assessment of quality of life across multiple domains and disease states, but may lack sensitivity to the specific challenges of neuromuscular disorders.

The Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Quality of Life (DMD-QoL) scoring system is a 14-item, disease-specific, patient-reported, outcome measure developed to assess quality of life in both pediatric and adult patients with DMD. The DMD-QoL scale captures domains, such as autonomy, daily activities, emotional well-being, identity, physical aspects, and social relationships [47]. The DMD-QoL is more sensitive to the unique experiences and disease progression in DMD than generic measures (e.g., WHOQOL-BREF), offering superior content validity and responsiveness. This enables more accurate assessment of treatment impact and supporting clinical decision-making and treatment response.

The Individualized Neuromuscular Quality of Life questionnaire (INQoL) is a 45-item, patient-reported outcome measure for adults with neuromuscular disorders. It covers 10 domains, including key symptoms (weakness, pain, fatigue, myotonia), and the impact on activities, independence, social relationships, emotions, and body image. Developed through patient interviews and large-scale surveys, INQoL demonstrates strong content validity and relevance [48]. It has been validated across a wide range of neuromuscular conditions and languages. Compared to generic tools, INQoL is more sensitive to the specific physical and psychosocial challenges of neuromuscular disease, including direct assessment of respiratory symptoms [49].

The ALSAQ-40 is a validated, disease-specific, patient-reported outcome measure for ALS that consists of 40 items across five domains: physical mobility, activities of daily living/independence, eating and drinking, communication, and emotional functioning; each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater impairment. The instrument is sensitive to changes in disease status, making it widely used for clinical monitoring. The ALSAQ-5 is a short-form version containing one item from each domain, providing a rapid assessment. Both tools are valued for their ability to capture the multidimensional impact of ALS on quality of life and efficacy of treatment [50,51].

The WHOQOL-BREF is a generic, 26-item quality of life instrument which assesses four broad domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. The WHOQOL-BREF is not specific to NMD, but it has been validated in these populations. Its broader scope allows for cross-disease comparisons, making it valuable in benchmarking against other conditions or populations [52].

Limitations of the ALSAQ-5 include its narrow focus on ALS-related symptoms and functional impairments, which may result in underrepresentation of broader psychosocial, environmental, or existential factors that also influence quality of life. Conversely, the WHOQOL-BREF offers a holistic assessment, it may lack sensitivity to the specific and nuanced challenges faced by individuals with ALS and other neuromuscular disorders, such as progressive loss of communication or swallowing ability.

Clinicians who encounter these patients can utilize quality of life instruments, not as a one size fits all approach, but choose which one or group is most cogent to individuals for longitudinally reviewing their perceptions of disease impact.

Incorporated Care Model

The undertaking of complex care for patients with progressive neuromuscular disease living with mechanical ventilation support is most successful with multidisciplinary clinical care approaches. We propose a longitudinal schematic that incorporates initially choosing quality of life metrics to follow based on patient diagnosis or phenotype, introductory dialogue with caregivers to allow bidirectional learning and create alliances that value caregiver dynamics, and allowing patients to explore life expectancy pragmatically. Figure 2 this model offers elasticity between varying neuromuscular diseases and age groups by focusing on generalizable aspects of living with, and ultimately dying from, a progressive and incurable condition and fosters participation between the three parties of interest: the patient, the caregiver, and the health care provider. This can also be incorporated before undertaking mechanical ventilation or after patients have been living with mechanical ventilation support, as it offers ongoing and adaptable consideration of where patients' goals for life align with the biological state of their disease.

Summary

Patients living with progressive neuromuscular disorders face long-term challenges and often live supported by mechanical ventilation devices for prolonged periods of time. This cohort has disproportionate use of ambulatory and hospital health care as their diseases progress given their complex nature and comorbidities. Engaging in end-of-life care discussions with them and their caregivers requires sensitivity and gaining knowledge not just about their diagnosis but about their perceived quality of life, the impact the disease has on caregiver well-being and mental health and an approach that builds a relationship around open dialogue centered on these aspects.

We outline a structured model that incorporates several key aspects of living with, and ultimately dying from neuromuscular disease, assessment of this impact on caregivers, and patient quality of life. While not precise at predicting time to death its strengths lie in its generalizable approach to adult and childhood neuromuscular disorders, applicability at any point in their disease progression, and establishing relationships between health care providers, patients and the people who are impacted by taking care of them.

Funding

None.

References

- Gong Y, Sankari A (2025) Noninvasive Ventilation. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID: 35201716.

- Annunziata A, Calabrese C, Simioli F, Coppola A, Flora M, et al. (2022) Negative-Pressure Ventilation in Neuromuscular Diseases in the Acute Setting. J Clin Med 11: 2589.

- Romero-Ávila P, Márquez-Espinós C, Cabrera-Afonso JR (2020) The history of mechanical ventilation. Rev Med Chil 148: 822-830.

- Ito-Shinjo A, Shinjo D, Nakamura T, Kubota M, Fushimi K (2025) Risk factors associated with unplanned readmissions and frequent out-of-hour emergency department visits after pediatric tracheostomy: a nationwide inpatient database study in Japan. Eur J Pediatr 184: 422.

- Lai K, Fireizen Y, Morphew T, Randhawa I (2023) Pediatric Patients with Tracheostomies and Its Multifacet Association with Lower Airway Infections: An 8-Year Retrospective Study in a Large Tertiary Center. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol 36: 133-142.

- Stenson K, Chew S, Dong S, Heithoff K, Wang MJ, et al. (2024) Health care resource utilization and costs across stages of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 30: 1239-1247.

- Pisa FE, Logroscino G, Giacomelli Battiston P, Barbone F (2016) Hospitalizations due to respiratory failure in patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and their impact on survival: a population-based cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 16: 136.

- Ackrivo J, Elman L, Hansen-Flaschen J (2021) Telemonitoring for Home-assisted Ventilation: A Narrative Review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 18: 1761-1772.

- Klimchak AC, Szabo SM, Qian C, Popoff E, Iannaccone S, et al. (2021) Characterizing demographics, comorbidities, and costs of care among populations with Duchenne muscular dystrophy with Medicaid and commercial coverage. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 27: 1426-1437.

- Foster CC, Florin TA, Williams DJ, Freundlich KL, Steuart RL, et al. (2025) Ramgopal S. Care Utilization for Acute Respiratory Infections in Children Requiring Invasive Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation. Pediatr Pulmonol 60: 71026.

- Davidson ZE, Vidmar S, Griffiths A, Howard ME, Berlowitz DJ, et al. (2025) Survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Australia: A 50-year retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 58: 101568.

- Weng WC, Chan SHS, Gomez R, Wang F, Chou HW, et al (2025) management in Asia: Current challenges and future directions. J Neuromuscul Dis 12: 22143602241297846.

- Castro D, Sejersen T, Bello L, Buccella F, Cairns A, et al. (2025) Transition of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy from paediatric to adult care: An international Delphi consensus study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 54: 130-139.

- Jensen HAR, Davidsen M, Brønnum-Hansen H, Eliasen MH, Christensen AI (2025) Trends in educational inequality in healthy life expectancy in Denmark between 2010 and 2021: A population-based study. BMJ Open 15: 100851.

- GBD 2017 US Neurological Disorders Collaborators, Feigin VL, Vos T, Alahdab F, Amit AML, et al. (2021) Burden of Neurological Disorders Across the US From 1990-2017: A Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Neurol 78: 165-176.

- Ryder S, Leadley RM, Armstrong N, Westwood M, de Kock S, et al. (2017) The burden, epidemiology, costs and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an evidence review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 12: 79.

- Radunovic A, Annane D, Rafiq MK, Brassington R, Mustfa N (2017) Mechanical ventilation for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 10: CD004427.

- Spittel S, Maier A, Kettemann D, Walter B, Koch B, et al. (2021) Non-invasive and tracheostomy invasive ventilation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Utilization and survival rates in a cohort study over 12 years in Germany. Eur J Neurol 28: 1160-1171.

- Fayssoil A, Ogna A, Chaffaut C, Chevret S, Guimarães-Costa R, et al. (2016) Natural History of Cardiac and Respiratory Involvement, Prognosis and Predictive Factors for Long-Term Survival in Adult Patients with Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophies Type 2C and 2D. PLoS One 11: 153095.

- Silva IS, Pedrosa R, Azevedo IG, Forbes AM, Fregonezi GA, et al. (2019) Respiratory muscle training in children and adults with neuromuscular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9: 11711.

- Straub V, Guglieri M (2023) An update on Becker muscular dystrophy. Curr Opin Neurol 36: 450-454.

- Smith CA, Gutmann L (2016) Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 Management and Therapeutics. Curr Treat Options Neurol 18: 52.

- Gomez-Merino E, Bach JR (2002) Duchenne muscular dystrophy: prolongation of life by noninvasive ventilation and mechanically assisted coughing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 81: 411-415.

- Gladman M, Dehaan M, Pinto H, Geerts W, Zinman L (2014) Venous thromboembolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a prospective study. Neurology 82: 1674-1677.

- Berry JD, Korngut L (2014) Reevaluating the risk of DVT in people with ALS: weak in the knees and DVTs. Neurology 82: 1668-1669.

- Takeda T, Koreki A, Kokubun S, Saito Y, Ishikawa A, et al. (2024) Deep vein thrombosis and its risk factors in neurodegenerative diseases: A markedly higher incidence in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci 457: 122896.

- Nakamura A, Matsumura T, Ogata K, Mori-Yoshimura M, Takeshita E, et al. (2023) Natural history of Becker muscular dystrophy: a multicenter study of 225 patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 10: 2360-2372.

- Chan LLY, Okubo Y, Brodie MA, Lord SR (2020) Mobility performance predicts incident depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Gerontol 142: 111116.

- Rosenberg DE, Bombardier CH, Artherholt S, Jensen MP, Motl RW (2013) Self-reported depression and physical activity in adults with mobility impairments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94: 731-736.

- Fang F, Valdimarsdóttir U, Fürst CJ, Hultman C, Fall K, et al. (2008) Suicide among Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain 131: 2729-2733.

- Lund EM, Hostetter TA, Forster JE, Hoffmire CA, Stearns-Yoder KA, et al. (2021) Suicide among Veterans with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle & Nerve 63: 807-811.

- de Die-Smulders CE, Höweler CJ, Thijs C, Mirandolle JF, Anten HB, et al. (1998) Age and Causes of Death in Adult-Onset Myotonic Dystrophy. Brain 121: 1557-1563.

- Sukockiene E, Ferfoglia RL, Poncet A, Janssens J-P, Allali G, et al (2021) Longitudinal Timed Up and Go Assessment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. European Neurology 84: 375-379.

- McDonald, Craig M, Abresch RT, Duong T, Joyce NC, et al. (2018) Long-Term Effects of Glucocorticoids on Function, Quality of Life, and Survival in Patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Prospective Cohort Study. The Lancet (British Edition) 391: 451-461.

- Chung Y, Garden FL, Marks GB, Vedam H (2023) Causes of Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure and Associated In-hospital Mortality. Respirology 28: 176-182.

- Greenaway LP, Martin NH, Lawrence V, Janssen A , Al-Chalabi A, et al. (2015) Accepting or Declining Non-Invasive Ventilation or Gastrostomy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Patients’ Perspectives. Journal of Neurology 262: 1002-1013.

- Pattee, Gary L (2025) Gastrostomy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Timing Enhances Survival. Muscle & Nerve 71: 3-5.

- Dorst J, Dupuis L, Petri S, Kollewe K, Abdulla S, et al. (2015) Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Neurology 262: 849-858.

- Ng ASL, Rademakers R, Miller BL (2015) Frontotemporal Dementia: A Bridge between Dementia and Neuromuscular Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1338: 71-93.

- Skillbäck T, Mattsson N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2017) Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light concentration in motor neuron disease and frontotemporal dementia predicts survival. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 18: 397-403.

- van der Sluijs, BM (2017) Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy with Frontotemporal Dementia European Geriatric Medicine 8: 81-83.

- Huang CC, Kuo HC (2005) Myotonic dystrophies. Chang Gung Med J 28: 517-526.

- Laurey B, Hoffman K, Corbo-Galli C, Dong S, Zumpf K, et al. (2024) Use of the Assessment of Caregiver Experience with Neuromuscular Disease (ACEND) in Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Journal of Clinical Medicine 13: 921.

- Lo SH, Lawrence C, Martí Y, Café A, Lloyd AJ, et al. (2022) Patient and Caregiver Treatment Preferences in Type 2 and Non-Ambulatory Type 3 Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Discrete Choice Experiment Survey in Five European Countries.” Pharmaco Economics 40: 103-115.

- Benedetto L, Musumeci O, Giordano A, Porcino M, Ingrassia M, et al. (2023) Assessment of Parental Needs and Quality of Life in Children with a Rare Neuromuscular Disease (Pompe Disease): A Quantitative–Qualitative Study. Behav Sci (Basel)13: 956.

- Veronika W, Patch C, Mahrer-Imhof R, Metcalfe A (2021) The Family Transition Experience When Living with Childhood Neuromuscular Disease: A Grounded Theory Study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 77: 4, 1921-1933.

- Powell PA, Carlton J, Rowen D, Chandler F, Guglieri M, et al. (2021). Development of a New Quality of Life Measure for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using Mixed Methods: The DMD-QoL. Neurology 96: 2438-2450.

- Vincent KA, Carr AJ, Walburn J, Scott DL, Rose MR (2007). Construction and validation of a quality-of-life questionnaire for neuromuscular disease (INQoL). Neurology 68: 1051-1057.

- Crescimanno G, Greco F, D'Alia R, Messina L, Marrone O (2019) Quality of life in long term ventilated adult patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 29: 569-575.

- Zahir F, Hanman A, Yazdani N, La Rosa S, Sleik G, et al. (2023). Assessing the psychometric properties of quality-of-life measures in individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 32: 2447-2462.

- Stenson K, Fecteau TE, O'Callaghan L, Bryden P, Mellor J, et al. (2024). Health-related quality of life across disease stages in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results from a real-world survey. Journal of neurology, 271: 2390-2404.

- Skevington SM, Epton T (2018) How will the sustainable development goals deliver changes in well-being? A systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate whether WHOQOL-BREF scores respond to change. BMJ global health 3: 609.

Citation: Scullin D, Flueckiger B, Barney J (2025) Approach to End-of-Life Care in Patients with Neuromuscular Disorders Utilizing Mechanical Ventilatory Support. J Pulm Med Respir Res 11: 093.

Copyright: © 2025 Daniel Scullin, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.