Bored Boys Bet: Predictors of Sports Gambling Behavior by University Students during the COVID-19 Lockdown

*Corresponding Author(s):

Goernert PNDepartment Of Psychology, Brandon University, Brandon, MB R7A 6A9, Canada

Tel:+1 2045717856,

Email:goernertp@brandonu.ca

Abstract

A state of emergency was declared on March 27, 2020 in the province of Manitoba due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For three months, the population of Manitoba was confined to their homes; social contact was restricted to grocery shopping, medical appointments and medical prescription purchases. Mental health professionals raised concerns that because of the lockdown, there would be increases in addictive behaviors and other mental health issues among vulnerable populations. The present study examined sports betting in what a number of studies report is an at risk population, university-age males. University students (N = 155) completed measures assessing the risk of gambling problems (the PGSI), participant’s endorsement of the rationale underlying the lockdown, the degree to which they felt that the lockdown negatively impacted their lives, and their level of boredom during the pandemic. Males who scored high on measures of boredom proneness wagered more on sports and gambled more often than did males scoring low on the boredom proneness measure; females’ gambling behavior was unrelated to their level of boredom proneness. Reasons for the gender differences in gambling behavior and the nature of the boredom proneness concept and measure were discussed.

Keywords

Boredom proneness; COVID; Gambling risk; Lockdown; Sport betting

Introduction

Approximately, 80% of post-secondary students report that they have participated in various types of gambling [1]. In their meta-analysis, Nowak and Aloe [2] found that post-secondary students maybe significantly more likely to gamble than other age groups; an outcome Nowak and Aloe [2] attribute to increased risk taking, and the increased acceptance, legalization and accessibility of online gambling sites. With numerous online gambling options available, the accessibility of online gambling is a concern since post-secondary students appear to be the fastest growing group of internet gamblers [3]. There are many online gambling options available to the willing consumer, and of those, sports gambling is receiving increased attention from researchers, politicians and policy makers as many countries have or are considering legalizing this form of online gambling [4], and there are sound reasons for these concerns. Sports gambling are one of the most strongly endorsed forms of gambling by individuals experiencing gambling problems [5]. More ominously, the internet and sports gambling conversion rate (proportion of people who try the activity and subsequently play that activity) was higher for sports gambling than for any other form of gambling activity [6,7]. Other reasons for concerns about sport gambling are the risk factors associated with the activity. Several studies report an association between sports gambling and being male, educated, and a full-time student [3,8,9]. Wang, Won and Jeon [10] argue that male college students are at risk of exposure to various sport betting activities, and, this in turn may lead to future gambling-related problems. Castrén, Basnet, et al., [11] reported that being young and male was the most significant predictor of problem gambling [4,12,13].

Gambling during COVID-19

The World Health Organization declared a global-wide pandemic on March 11, 2020, [14] and soon thereafter on March 27, 2020 the province of Manitoba declared a state of emergency prohibiting social gatherings larger than 10, gatherings that included concerts, funerals, weddings and casinos. For about three months, the Government of Manitoba confined the population to the space of their homes (referred to as ‘the lockdown’). Social contact was limited to food shopping, picking-up prescription medication and medical appointments. Regulators, policymakers, and treatment organizations speculated that mental health concerns and addictive behaviors (and online gambling in particular) would increase as people try to cope with the unprecedented social isolation and boredom [15,16]. There is, however, limited research to support these concerns. In the only study we are aware of that examined these questions, Håkansson [17] found that social isolation was associated with increased gambling among problem gamblers; among non-problem gamblers, social isolation was unrelated to increases in gambling activity.

The results of Håkansson [17] have a number of implications for the present study. If, as noted above, sports gambling is more likely to occur among male than female university students, then one consequence the COVID-19 lockdown, is that males but not females should report higher rates of online gambling. More critically, the Håkansson [17] study contained problem gamblers consistent with a majority of research literature that focuses on harmful levels of gambling [18]. On the other side of the coin, results of the lockdown on (largely) non-problem gamblers remains unexplored. In DSM 5, problem gambling is categorized as an impulse-control disorder [19] because problem gambling has (among other attributes) a compulsive [20] quality not present in non-problem but frequent gamblers. Among non-problem gamblers, the motivation to gamble may differ from that found in problem gamblers. The present study explored these ideas by asking university students to complete a measure assessing their level of gambling risk (Problem Gambling Severity Index, PGSI; Ferris & Wynne [21]) and an individual difference measure, boredom proneness, a measure that past studies [15,22] report to be associated with gambling behavior. Caroll and Huxley [15] claim that boredom is among the primary motivators for engaging in gambling activity [23]. One implication of these ideas is that male (but not female) university students who report being bored during the lockdown are more likely to report more sports betting and online gambling generally than males who report low levels of boredom.

The lockdown may have produced more than a population of bored people. A number of studies [24,25] report increased stress among respondents as a result restrictions on social gatherings, personal freedom and disruptions of daily routines. Gambling may be one way to reduce stress by temporarily distracting people from their frustrations and anxiety [17,26]. This idea was tested here by asking participants to indicate the degree to which the lockdown disrupted their daily routines and their relationships with friends and family. While the negative impact of the lockdown has been the focus of attention, many people do appear to be unaffected by the restrictions. While there are probably many reasons why some just went on with lives during the lockdown, in the present study we focus on one explanation, organizational citizenship. Organizational citizenship behaviors refer to employee who acts in ways that support the broader social and psychological environment of the organization [27]. To the extent that a participant agrees with the rationale underlying the lockdown, we can infer that they support the broader social and psychological environment created by the restrictions, and, as a result, have a ready explanation for why they must stay at home. One implication of these ideas is that those who endorse the lockdown rational should gamble less than those who oppose the restrictions. This is the case because by endorsing the lockdown rationale and its’ consequences, participants can adopt the self-perception of civic virtue and upholding the social good. These ideas were tested in the present study by assessing the degree to which endorsement of the lockdown predicted sports gambling during the pandemic.

Predicted relationships

The present study examined the relationship between risk of gambling problems, age, gender, boredom proneness and sports gambling. From our review of the literature, we hypothesized that males more so than females will be more likely to engage in sports betting [9,12]. Second, we expect boredom proneness to interact with gambling risk producing higher levels of sports gambling, this effect being greater for males than females [22]. Third, recent research indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic brought significant disruptions to daily routines [25]. It may be that participants who feel that their lives were negatively impacted by the lockdown or those who disagreed with reasons for the lockdown might increase their sports gambling as a way of reducing stress or restoring a sense of personal freedom, particularly among those at risk for gambling problems. To test these hypotheses, the interaction between perceived disruption and gambling risk and acceptance of the lockdown restrictions and gambling risk was regressed on the frequency of sports gambling.

Methods

Participants

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, the dean of students distributed an email to the student campus community (N = 3,689). The email included a brief description of the study, a link to a series of questions, and a consent form (ethics file #22747). The final sample contained 35 males (22.5%) and 120 females (77.4%) for a 4.2% response rate.

Materials

The survey contained sociodemographic questions such as gender, age and living conditions. Gambling behaviors questions were modeled after those used by Håkansson [16]. A question about type of gambling activities done in the past year was measured by placing a check mark beside each of the nine types of gambling (e.g., slots, horserace betting, and cards). Sports betting was assessed by responses to an estimate of how many times per week participants gambled on sports. The overall level of gambling during the lockdown was measured by responses to the query‘ how many times per week did you gamble during the lockdown’? Responses to the gambling questions were made on appropriately labelled 7-point scales (1 = I did not gamble (on sports) to 7 = I gambled a lot (on sports)). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on participants’ daily lives was measured by asking how strongly (1= strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) participants endorsed the provincial health order to remain at home during the lockdown, and to estimate the degree to which (1 = not very much to 7 = a great deal) the pandemic negatively impacted daily activities.

The Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) was used to assess gambling-related problems. On each of the nine scale items, participants indicated whether they never (scored zero), sometimes (scored one), most of the time (scored two), and almost always (scored three) experienced a gambling-related problem (α = 0.83 in this sample). Summing responses from the nine items results in a total PGSI score. A score of zero indicates an individual displays no risk for experiencing gambling problems; a score of eight or more indicates a high-level risk for experiencing gambling problems [28]. A short form of the Boredom Proneness Scale [29] was used to assess boredom during the early months of the pandemic. On each of the eight items (e.g. ‘I find it hard to entertain myself’, ‘I don’t feel motivated by most things I do’), participants responded on a five point (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; α = 0.87 in this sample) scale.

Procedure

When students received the dean of students email, they were asked to read the description of the study, and if they opted to participate, to read the consent form. A statement at the bottom of the consent form emphasized that clicking the link to the survey and filling out the survey was implied consent. After giving their consent, participants proceeded to the survey.

Data analysis

Prior to data analysis, all continuous predictor variables (PGSI scores, endorsement of remaining at home during the lockdown, level of negative impact of COVID and boredom proneness scores) were centered to prevent problems associated with multicollinearity [30]. In line with our predictions, two-way interactions were created between the centralized variables and the gender and age variables, a three-way interaction was created between gender, boredom proneness and PGSI.

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was used to assess relationships between sport gambling, continuous variables and their interactions. In the first of three steps in the analysis age, gender, level of negative impact of COVID, PGSI scores, time spent at home, and boredom proneness were regressed on the number of time per week participants bet on sports. In step two, the two-way interactions were entered, and in step three, the 3-way interaction was included.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 reports a summary of the descriptive statistics and table 2 contains the correlations among variables. PGSI scores (M = 1.32, SD = 2.73) indicates that on average participants’ displayed a relatively low risk for experiencing gambling problems. Estimates of the average number of times participants gambled on sports correlated with gender (r = 0.280), age (r = 0.185) and PGSI scores (r= 0.340). Agreement with stay at home orders, level of boredom proneness, and degree to which participants felt that they were being negatively impacted by COVID were not significantly related to sport betting (all p’s > 0.05).

|

Variable |

M |

SD |

Range |

|

Age |

22 |

5.37 |

18 - 50 |

|

PGSI |

1.32 |

2.73 |

0 - 18 |

|

Endorsed remaining at home |

6.42 |

1.03 |

1 - 7 |

|

Boredom proneness scale |

17.79 |

6.78 |

8 - 35 |

|

Negatively impacted by COVID |

5.47 |

1.59 |

1 - 7 |

|

Estimate of weekly sports gambling bets |

0.35 |

1.22 |

0 - 10 |

|

Estimate of gambling during lockdown |

0.71 |

1.99 |

0 - 10 |

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for variables of interest.

|

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Gender |

- |

0.117 |

0.158 |

-0.034 |

-0.113 |

-0.138 |

0.28 |

0.352 |

|

Age |

- |

- |

0.159 |

0.053 |

-0.166 |

-0.098 |

0.185 |

0.18 |

|

PGSI |

- |

- |

- |

-0.163 |

0.224 |

-0.003 |

0.34 |

0.312 |

|

Remaining at home |

- |

- |

- |

- |

-0.176 |

0.347 |

-0.003 |

-0.001 |

|

Boredom proneness |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.077 |

0.038 |

0.141 |

|

Negative impact |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.003 |

0.002 |

|

Estimate of weekly sports gambling bets |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.802 |

|

Gambling during pandemic |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Table 2: Zero-Order correlations among predictor and criterion variables.

Notes. N=155. Gender code 1 = Female, 2 = Male. Spearman's rho examined all relationships with gender. Pearson correlation examined relationships among all other variables. Correaltions in italics p < 0.05. Correlations in bold p < 0.01.

Sports betting

In step 1 of the hierarchical regression, gender, age, level of being negatively impacted by COVID, level of agreement with lockdown restrictions, PGSI scores and level of boredom proneness were regressed on estimates of sports betting. The first model was significant F (6,144) = 5.219, p< 0.001, AdjR2 = 0.144. As can be seen in table 3, Gender (β = 0.218, t (151) = 2.821, p < 0.005) and PGSI scores (β = 0.288, t (151) = 3.575, p < 0.001) were related to sports gambling. No other predictors reached significance. Interaction terms for each predictor pair were entered in step 2, and while this model was significant (F (15, 135) = 3.668, p< 0.001, AdjR2 = 0.211), there was no significant increase in the variance accounted for beyond that found for the first model R2 = 0.295, ΔF(1,134) = 1.062, p> 0.05. In the second model, PGSI scores were inversely related (β = -0.828, t (151) = -1.977, p < 0.05) to the frequency of sports gambling. No other predictors reached significance.

|

Variable |

B |

SE B |

β |

|

Step 1 |

|||

|

Gender |

0.636 |

0.226 |

.218** |

|

Age |

0.028 |

0.018 |

0.121 |

|

Negatively Impacted by COVID |

0.019 |

0.064 |

0.024 |

|

Endorsed Remaining at Home |

0.037 |

0.100 |

0.03 |

|

PGSI |

0.131 |

0.037 |

.288** |

|

Boredom Proneness |

0.004 |

0.015 |

0.02 |

|

Step 2 |

|||

|

Gender |

0.98 |

1.146 |

0.336 |

|

Age |

0.048 |

0.065 |

0.209 |

|

Negatively Impacted by COVID |

0.301 |

0.366 |

0.389 |

|

Endorsed Remaining at Home |

0.814 |

0.654 |

0.657 |

|

PGSI |

-0.376 |

0.19 |

-.828* |

|

Boredom Proneness |

-0.113 |

0.084 |

-0.621 |

|

Gender x Age |

-0.02 |

0.052 |

-0.203 |

|

Gender x Negatively Impacted by COVID |

-0.122 |

0.167 |

-0.199 |

|

Gender x Endorsed Remaining at Home |

-0.25 |

0.288 |

-0.245 |

|

Gender x PGSI |

0.152 |

0.092 |

0.444 |

|

Gender x Boredom Proneness |

0.07 |

0.037 |

0.48 |

|

Age x Negatively Impacted by COVID |

-0.006 |

0.011 |

-0.203 |

|

Age x Endorsed Remaining at Home |

-0.024 |

0.03 |

-0.444 |

|

Age x PGSI |

0.015 |

0.008 |

0.765 |

|

Age x Boredom Proneness |

0.002 |

0.003 |

0.196 |

|

Step 3 |

|||

|

Gender |

0.747 |

1.168 |

0.256 |

|

Age |

0.747 |

0.065 |

0.179 |

|

Negatively Impacted by COVID |

0.23 |

0.373 |

0.298 |

|

Endorsed Remaining at Home |

0.778 |

0.655 |

0.645 |

|

PGSI |

-0.916 |

0.558 |

-2.019 |

|

Boredom Proneness |

-0.112 |

0.084 |

-0.619 |

|

Gender x Age |

-0.007 |

0.053 |

-0.132 |

|

Gender x Negatively Impacted by COVID |

-0.801 |

0.172 |

-0.132 |

|

Gender x Endorsed Remaining at Home |

-0.240 |

0.288 |

-0.236 |

|

Gender x PGSI |

0.507 |

0.357 |

1.487 |

|

Gender x Boredom Proneness |

0.073 |

0.038 |

0.497* |

|

Age x Negatively Impacted by COVID |

-0.006 |

0.011 |

-0.179 |

|

Age x Endorsed Remaining at Home |

-0.023 |

0.030 |

-0.420 |

|

Age x PGSI |

0.039 |

0.025 |

2.041 |

|

Age x Boredom Proneness |

0.001 |

0.003 |

0.178 |

|

Gender x Age x PGSI |

-0.016 |

0.015 |

-1.208 |

Table 3: Hierarchical multiple regression analysis for variables predicting participants’ estimate of their weekly sports gambling bets.

Note: AdR2 = 0.144 for Step 1 (p < 0.001); AdR2 = 0.211 for step 2 (p = 0.017); AdR2 = 0.211 for Step 3 (p > 0.05) * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001.

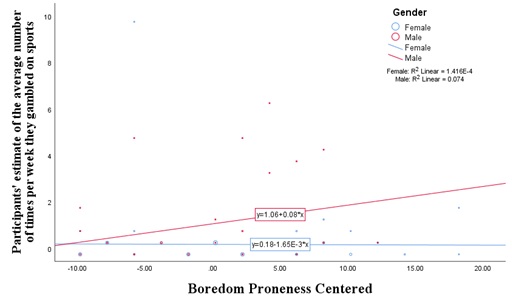

In the final step, the 3-way interaction term Gender xAge x PGSI scores to the model. This model was significant, F (16, 134) = 3.507, p< 0.001, AdjR2= 0.211, as was the increase in proportion of variance accounted over the model contained in step 2 (R2 = 0.290, ΔF (9,135) = 2.342, p = 0.017. More central to our concerns, the predicted Gender x Boredom Proneness was also significant (β = 0.497, t (151) p < 0.05). As can be seen in figure 1, gender moderated the relationship between boredom proneness and the number of times participants reported they gambled on sports. For men, boredom proneness accounted for 7.4% of the variability in sports gambling; among women, boredom proneness accounted for nearly none of the variability in sports gambling. No other predictors were significant.

Figure 1: Relationship between Boredom Proneness and Sports Betting by male and female participants.

Figure 1: Relationship between Boredom Proneness and Sports Betting by male and female participants.

To explore the Gender x Boredom Proneness interaction more fully, participant scores on the Boredom Proneness scale were split at the median into high and low boredom proneness groups. A 2 (Boredom Proneness) x 2 Gender (Male, Female) analysis of variance on sports betting revealed an effect of Gender (F (1, 149) = 14.41, MSE = 1.336, n2 = 0.088, p< 0.001) and Boredom Proneness F (1, 149) = 6.652, MSE = 1.336, n2 = 0.043, p = 0.011. The Gender x Boredom Proneness interaction was also significant, F (1, 149) = 9.404, MSE = 1.336, n2 = 0.059, p = 0.003. Because there were unequal numbers of men and women participants, the Mann-Whitney test was used to determine simple main effects. This test indicated that low boredom proneness men did not make significantly more sports per week (M = 0.40, SD = 1.118) than low boredom proneness women (M = 0.24, SD = 1.36, U = 506.00, p> 0.05). High boredom prone men, however, made significant more sports bets per week (M = 1.67, SD = 2.127) than high boredom prone women (M = 0.13, SD = 0.387, U = 257.00, p< 0.001).

Gambling behavior during the lockdown

A hierarchical regression analysis similar to that described above but with the participant’s estimates of how much they gambled during the lockdown yielded results similar to that described above with one exception, boredom proneness was inversely related to the total amount of gambling during the lockdown (β = -1.005, t (151) = -2.43, p = 0.017). This relationship was modified by the predicted Gender x Boredom interaction (β = 0.775, t (151) = 3.351, p< 0.001), and, as in the previous analysis, boredom prone males were more likely to gamble (β = 0.357, t (33) = 2.196, p< 0.035), than less bored males. Female gambling was not significantly related to boredom proneness β = 0.152, t (116) = 1.66, p < 0.099).

Supplementary findings

It was hypothesized that participants who were perceived that their lives were negatively impacted by the lockdown would gamble more than those than those who felt that the lockdown was less of an imposition. As can be seen in table 3 there was little support for this idea. The perceived impact of the lockdown was not significantly related to changes in sports betting. It was also suggested that endorsement of lockdown as a means to control viral spread would reduce sports betting because participants would have an explanation for why their lives were being constrained. A second hierarchical multiple regression analysis examined whether endorsement of lockdown measures as a predictor, or in combination with gender, PGSI, and boredom proneness predicted sports gambling. In neither step 1, as a predictor, nor in steps 2 and 3 in interaction with other predictors, did endorsement of the lockdown predict sports betting (all regression weights p> 0.05). The hierarchical regression revealed significant outcomes almost identical to that reported in table 3.

Discussion

We hypothesized that gender, age, and PGSI scores would interact to predict sports gambling activity during the lockdown. Our findings did not support this prediction. Gender and PGSI, however, did significantly predict sports gambling activity during the lockdown. In addition, a significant gender by boredom proneness interaction revealed that bored males were more likely to sports bet, and to participate in other gambling activities as well; among women, boredom proneness was unrelated to sports betting or gambling during the pandemic. It was also hypothesized that more betting would occur among those who showed evidence of gambling problems and who did not endorse the lockdown. There was little support for this hypothesis. Neither endorsement of the lockdown or the interaction with boredom approached significance. Only PGSI and gender significantly directly predicted gambling increases during the lockdown. These results imply that for high scorers on the PGSI, time spent at home during lockdown did not influence the frequency of gambling activities. These results are consistent with those of Håkansson [17] who reported a relatively weak correlation between spending more time at home and gambling increases during the lockdown.

One implication of the results of this study is that even when individuals score low on the PGSI, those scores were predictive of estimates of gambling done during the pandemic generally and sports specifically, a finding consistent with those of Russell et al., [7]. Russell et al., [7] found that in addition to problem-gamblers, even moderate- and low-risk gamblers placed a significantly more bets on days when they did bet on sports compared to non-problem gamblers. Moreover, compared to non-problem gamblers, low- and moderate-, and problem-gamblers all had significantly higher numbers of accounts and bet larger amounts, compared to non-problem gamblers. Taken together, results of the present study and those of Russell, et al., [7] suggest even low PGSI scores predicts gambling behavior.

A number of studies report relationships between being male, educated, and a full-time student and gambling behaviors [3,9-11]. One explanation of these gender differences is that males, more so than females, report feeling bored, and boredom susceptibility has been suggested as one explanation underlying gambling behavior [31]. In the present study, level of boredom proneness mediated the relationship between gender and gambling behavior and sports betting in particular. To be fair, while some studies report a link between boredom susceptibility and risk taking behaviors such as gambling [32]; other studies have questioned that relationship [23]. Russell, et al., [7], for example, argue that motivations underlying sports betting included suspense and adrenaline seeking; suppressing boredom was of lesser influence. Mercer & Eastwood [31] found that boredom susceptibility not boredom proneness predicted gambling behaviors.

One reason why research on the gambling-boredom proneness link has yielded inconsistent results may be that boredom proneness is a proxy variable representing components of other variables. Mercer & Eastwood [31], for example, suggest that high scores on the boredom proneness scale reflect an avoidance of feelings of depression and loneliness that often accompanies boredom. On the other side of the coin, boredom proneness may reflect motivations such as sensation seeking and a desire to achieve a high state of arousal or at least increased arousal when placing bets and waiting for the outcome [33]. From this perspective, boredom prone males are more concerned about the adrenalin rush of the gamble that warding off feelings of depression and loneliness. Consistent with this idea, high boredom scorers like those who score high on impulsivity and sensation seeking measures are likely to engage in sports and other types of gambling [34-36]. Future studies may wish to examine the relationship between sensation seeking and impulsivity (while controlling for boredom proneness) and gambling among those who (as in the present study) show relatively few gambling problems.

Several studies report more gambling problems among males than females [12,11,37]. While we did not find a significant relationship between gender and gambling risk, scores on the PGSI did predict the number of bets placed per week during the lockdown even among those who did not place a large number of bets per week. This finding speaks to the construct validity of the gambling risk measure across the range of gambling behaviors and argues for increased use of the measure in future studies. On an applied level, the finding that low levels of PGSI predicts sports betting suggests that even among these scorers some conversion of some of the present sample to frequent sports betting can be anticipated [6,7], a distressing possibility that merits future research.

References

- Lostutter TW, Lewis MA, Cronce JM, Neighbors C, Larimer ME (2014) The use of protective behaviors in relation to gambling among college students. J Gambl Stud 30: 27-46.

- Nowak DE, Aloe AM (2014) The prevalence of pathological gambling among college students: A meta-analytic synthesis, 2005-2013. J Gambl Stud30: 819-843.

- Williams RJ, Connolly D, Wood RT, Nowatzki NR (2006) Gambling and problem gambling in a sample of university students. Journal of Gambling Issues 16: 1-14.

- Winters KC, Derevensky JL (2019) A review of sports wagering: Prevalence, characteristics of sports bettors, and association with problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Issues 43.

- LaBrie R, Shaffer HJ (2011) Identifying behavioral markers of disordered Internet sports gambling. Addiction Research & Theory19: 56-65.

- Holtgraves T (2009) Gambling, gambling activities, and problem gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 23: 295.

- Russell AM, Hing N, Browne M, Li E, Vitartas P (2019) Who bets on micro events (microbets) in sports? J Gambl Stud35: 205-223.

- Engwall D, Hunter R, Steinberg M (2004) Gambling and other risk behaviors on university campuses. J Am Coll Health52: 245-256.

- Hing N, Russell AM, Vitartas P, Lamont M (2016) Demographic, behavioural and normative risk factors for gambling problems amongst sports bettors. J Gambl Stud32: 625-641.

- Wang X, Won D, Jeon HS (2021) Predictors of Sports Gambling among College Students: The Role of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Problem Gambling Severity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18: 1803.

- Castrén S, Basnet S, Salonen AH, Pankakoski M, Ronkainen JE, et al. (2013). Factors associated with disordered gambling in Finland. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 8: 1-10.

- Huang JH, Boyer R (2007) Epidemiology of youth gambling problems in Canada: A national prevalence study. Can J Psychiatry52: 657-665.

- Russell AM, Hing N, Browne M (2019). Risk factors for gambling problems specifically associated with sports betting. J Gambl Stud 35: 1211-1228.

- Hiscott J, Alexandridi M, Muscolini M, Tassone E, Palermo E, et al. (2020) The global impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 53: 1-9.

- Carroll D, Huxley JA (1994) Cognitive, dispositional, and psychophysiological correlates of dependent slot machine gambling in young people. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 24: 1070-1083.

- Håkansson A, Fernández-Aranda F, Menchón JM, Potenza MN, Jiménez-Murcia S (2020) Gambling during the COVID-19 crisis–a cause for concern. J Addict Med 14: 10.

- Håkansson A (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on online gambling-a general population survey during the pandemic. Front Psychol 11: 2588.

- Currie SR, Hodgins DC, Wang J, El-Guebaly N, Wynne H, et al. (2006) Risk of harm among gamblers in the general population as a function of level of participation in gambling activities. Addiction 101: 570-580.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA (Vol 10).

- Gonzalez-Ibanez A, Mora M, Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Ariza A, Lourido-Ferreira MR (2005) Pathological gambling and age: Differences in personality, psychopathology, and response to treatment variables. Addictive behaviors 30: 383-388.

- Ferris J, Wynne H (2001) The Canadian Problem Gambling Index Final Report. Canadian Center on Substance Abuse, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

- Blaszczynski A, McConaghy N, Frankova A (1990) Boredom proneness in pathological gambling. Psychological Reports 67: 35-42.

- Mercer-Lynn KB, Hunter JA, Eastwood JD (2013) Is trait boredom redundant? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 32: 897-916.

- Sharman S, Roberts A, Bowden-Jones H, Strang J (2021) Gambling in COVID-19 Lockdown in the UK: Depression, Stress, and Anxiety. Front Psychiatry 12:621497.

- Zheng C, Huang WY, Sheridan S, Sit CHP, Chen XK, et al. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic brings a sedentary lifestyle in young adults: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 6035.

- Salerno L, Pallanti S (2021) COVID-19 Related Distress in Gambling Disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 620661.

- Organ DW (1988) Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books/DC Heath and Com.

- Orford J, Wardle H, Griffiths M, Sproston K, Erens B (2010) PGSI and DSM-IV in the 2007 British Gambling Prevalence Survey: Reliability, item response, factor structure and inter-scale agreement. International Gambling Studies 10: 31-44.

- Struk AA, Carriere JS, Cheyne JA, Danckert J (2017) A short boredom proneness scale: Development and psychometric properties. Assessment 24: 346-359.

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, California, USA.

- Mercer KB, Eastwood JD (2010) Is boredom associated with problem gambling behaviour? It depends on what you mean by ‘boredom’. International Gambling Studies 10: 91-104.

- Kiliç A, Van Tilburg WA, Igou ER (2020) Risk-taking increases under boredom. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making33: 257-269.

- Cross CP, Cyrenne DLM, Brown GR (2013) Gender differences in sensation-seeking: A meta-analysis. Scientific Reports3: 1-5.

- Farhat LC, Wampler J, Steinberg MA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Hoff nRA, et al. (2021). Excitement-Seeking Gambling in Adolescents: Health Correlates and Gambling-Related Attitudes and Behaviors. Journal of Gambling Studies37: 43-57.

- Hing N, Li E, Vitartas P, Russell AM (2018) On the spur of the moment: Intrinsic predictors of impulse sports betting. Journal of Gambling Studies34: 413-428.

- Peterson E, Gjedde A, Rodell A, Cumming P, Møller A, et al. (2006) High sensation seeking men have increased dopamine binding in the right putamen during gambling, determined from raclopride binding potentials. NeuroImage 31: T168.

- Stark S, Zahlan N, Albanese P, Tepperman L (2012) Beyond description: Understanding gender differences in problem gambling. J Behav Addict 1: 123-134.

Citation: Goernert PN, Corenblum B and Simard VC (2022) Bored Boys Bet: Predictors of Sports Gambling Behavior by University Students during the COVID-19 Lockdown. J Addict Addictv Disord 9: 092.

Copyright: © 2022 Goernert PN, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.