Evaluating Construct Alignment of the PN Comprehensive Predictor and the NCLEX-PN Test Plan

*Corresponding Author(s):

Kari J. HodgeManager Of Psychometrics And Applied Research ATI, Ascend Learning, Leawood, KS, United States

Email:kari.hodge@ascendlearning.com

Abstract

Background: In order for nurse educators to ensure students are prepared for entry-level nursing practice nursing curriculum, assessments and learning activities should incorporate the NCLEX domains and client care needs categories. The CP exam is deliberately designed using the NCLEX-PN test plan to include clinical judgement, all nursing domains and client needs categories in order to provide a comprehensive assessment of students NCLEX readiness.

Method: A confirmatory factor analysis was used to analyze exam scores from over 4,547 nursing students to evaluate the PN Comprehensive Predictor hypothesized structure alignment to the NCLEX-PN blueprint categories and subcategories.

Results: The results of this study provided evidence that the Comprehensive Predictor assessment data fits the NCLEX-PN blueprint. The factor analysis suggests that nursing competence, as reflected in test performances, aligns with the NCLEX-PN blueprint categories and subcategories.

Conclusion: Consistent with RN research, the findings provided robust evidence of construct validity for the PN CP total score and sub-scores as meaningful indicators of entry-level nursing competence, which has implications for educational strategies and assessment practices in nursing education.

Introduction

There is an increasing demand for Licensed Practical Nurses (PN). Based on projections from the Health Resources and Services Administration [1] for 2026 there will be a 14% nursing shortage leaving more than 94,000 unoccupied positions. Furthermore, the Bureau of Labor Statistics [2], employment for Practical Nurses is projected to outpace the average growth rate for other occupations with an increase of 3 percent growth from 2023-2033. United States, Canada, and US territory requirements for PNs to practice include meeting state board educational requirements as well as passing the NCLEX-PN exam that is developed by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing [3,4]. In order for nurse educators to ensure students are prepared for entry-level nursing practice, the nursing curriculum, assessments and learning activities should incorporate the NCLEX domains and client care needs categories.

NCSBN conducts practice analysis for the NCLEX-PN test plan on a three-year cycle to ensure the test plan continues to be relevant to nursing practice and includes changes in the industry. The PN practice analysis conducted in 2024 revealed the continued need to include clinical judgment for entry-level activities including the decision-making skills required to ensure patient safety. The results of the 2024 practice analysis were consistent with the 2021 practice analysis. Based on the results from the 2021 practice analysis NCSBN updated the 2023 NCLEX-PN test plan to include clinical judgment referred to as the Next Generation NCLEX, or NGN.

In 2024, the PN practice analysis explored the relevance of clinical judgment on these entry-level activities. PNs apply specific knowledge and skills to meet the unique health needs of clients in a varied setting under the supervision of other licensed healthcare professionals. The results of the practice analysis are used to define the domains and client care needs categories on the NCLEX-PN (Table 1).

|

NCLEX-PN Categories |

Client Needs (PN Practice analysis percentage of time) |

Weight on NCLEX-PN |

|

Safe & Effective Care Environment |

Coordinated Care (11.0%) |

18-24% |

|

Safety & Infection Control (14.1%) |

10-16% |

|

|

Health Promotion & Maintenance |

Health Promotion and Maintenance (11.9%) |

6-12% |

|

Psychosocial Integrity |

Psychosocial Integrity (12.4%) |

9-15% |

|

Physiological Integrity |

Basic Care & Comfort (12.9%) |

7-13% |

|

Pharmacological & Parenteral Therapies (13.6%) |

10-16% |

|

|

Reduction of Risk Potential (12.4%) |

9-15% |

|

|

Physiological Adaptation (12.4%) |

7-13% |

Table 1: NCLEX-PN Categories, the PN Practice Analysis, and Weight on NCLEX-PN

PN nursing education includes various instructional and assessment activities that incorporate NCLEX-style questions, requiring students to demonstrate content knowledge as well as clinical judgment. The ATI Comprehensive Predictor (CP) is a standardized assessment taken near the end of the program as a measure of the accumulated knowledge gained during nursing school. The CP exam is deliberately designed using the NCLEX-PN test plan to include clinical judgment, all nursing domains and client needs categories in order to provide a comprehensive assessment of students’ NCLEX readiness and is not intended to be utilized in a high-stakes manner.

Previous research focused on the congruence between the factors used in the RN CP Assessment and the NCLEX-RN test plan [5]. The purpose of this study is to use a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) framework to examine the theoretical measurement structure of the PN CP exam to the client needs categories as outlined in the NGN and its integration of clinical judgment.

Methods

Data

The data sample for this study was derived from students’ first attempt on the 2023 PN CP exam. The sample includes data from all students who completed the exam during the 2023-2025 school years and was nationally representative. All records were de-identified and used in aggregate. This study was deemed exempt from BRANY institutional review board.

Our sample consisted of 4,547 students with the majority of between the ages of 21 and 43. Demographic variables also included gender, race, and language (Table 2). The largest group was Black or African American (31.7%), followed by White or European American (28.7%), and those of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (18.8%). English was overwhelmingly the most common language spoken (87.0%), followed by Spanish at 1.8%. The majority of the sample was female (82.7%) followed by male (9.8%).

|

Gender |

Race |

Language |

||||||

|

Variable |

Count |

Percent |

Variable |

Count |

Percent |

Variable |

Count |

Percent |

|

Female |

3,762 |

82.70% |

African American/Black |

1,440 |

31.70% |

English |

3,955 |

87.00% |

|

Male |

447 |

9.80% |

Asian |

334 |

7.30% |

French |

39 |

0.90% |

|

Other |

17 |

0.30% |

Caucasian/White |

1,303 |

28.70% |

Spanish |

80 |

1.80% |

|

No Response |

321 |

7.10% |

Hispanic |

856 |

18.80% |

Other |

473 |

10.40% |

|

|

|

|

Native American |

33 |

0.70% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other |

581 |

12.80% |

|

|

|

Table 2: Practical Nursing Student Demographics.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To rigorously assess the competencies of future nurses, especially in the critical area of clinical judgment, the theoretical measurement structure of the PN CP exam was investigated. The CP exam is purposefully engineered to mirror the content and hierarchical structure of the 2023 NCLEX-PN test plan, encompassing all major nursing domains and subdomains. Leveraging a CFA framework, our investigation delves into the theoretical structure underlying the measurement of client needs as defined by the 2023 NCLEX-PN test plan. This strategic alignment not only ensures a highly comprehensive evaluation of students’ entry-level nursing skills but also positions clinical judgment at the heart of the assessment process.

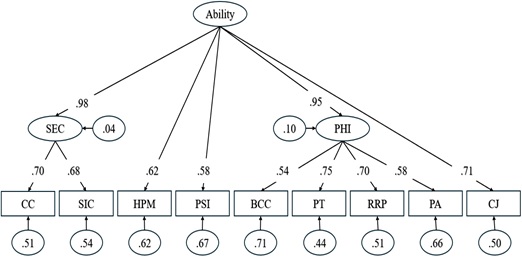

In the CFA model for the PN CP (Figure 1), the observed (manifest) variables, pictured as rectangles, represent scores from nine core content areas [6]:

- Management of Care (MC),

- Safety and Infection Control (SIC),

- Health Promotion and Maintenance (HPM),

- Psychosocial Integrity (PSI),

- Basic Care and Comfort (BCC),

- Pharmacological and Parenteral Therapies (PT),

- Reduction of Risk Potential (RRP),

- Physiological Adaptation (PA), and

- Clinical Judgement (CJ).

The latent variables, pictured as ovals, include Safety and Effective Care (SEC), Physiological Health Integrity (PHI), and a higher-order factor representing general entry-level nursing ability. This CFA model consists of a second order (or higher order) factors of nursing ability influencing directly two first order factors (SEC and PHI) and three manifest variables (HPM, PSI, and CJ).

Figure 1: Confirmatory Factor Model.

Figure 1: Confirmatory Factor Model.

Note: Recommended cut-off values for model fit indices in CFA:

- CFI (Comparative Fit Index) ≥ .90 (acceptable), ≥ .95 (excellent)

- TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) ≥ .90 (acceptable), ≥ .95 (excellent)

- RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) ≤ .08 (acceptable), ≤ .06 (excellent)

- SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) ≤ .08 (acceptable).

The model's directional paths demonstrate the structural connections between constructs: SEC is affected by MC and SIC, whereas PHI is shaped by BCC, PT, RRP, and PA. A higher-order factor explains the shared variance among SEC and PHI, along with the observable variables HPM, PSI, and CJ. Each observable variable is linked exclusively to one latent factor, in line with the 2023 NCLEX-PN test plan, thus preventing cross-loadings. Error variances are treated as random and uncorrelated, which is appropriate given the use of a single assessment tool and is supported by previous dimensional analyses. For model identification, the variance of the general ability factor was set to one. This configuration results in a coherent and interpretable model that aligns with current frameworks for nursing assessment. All statistical analyses were conducted using R 4.5.0 [7]. All parameters for the CFA were modeled using the lavaan package [8] in R software.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Overall, mean percent correct score of the observed variable were relatively high, ranging from 70.15 to 79.16, with both extremes observed in the Health Promotion Maintenance (HPM) and Safety and Infection Control (SIC) domain, respectively (Table 3). Most content areas exhibited moderate to high variability, with standard deviations spanning from 7.09 to 15.53. Clinical Judgment (CJ) showed the least variability (SD = 7.09), while Pharmacological Therapies (PT) had the highest (SD = 15.53). Score distributions covered nearly the entire possible range, with minimum values as low as 6.25 and maximums reaching 100. All items demonstrated negative skewness, indicating that scores tended to cluster toward the higher end. Kurtosis values were generally close to zero, suggesting approximately normal distributions. However, Coordinated Care and Clinical Judgment stood out with higher kurtosis values (1.54 and 1.44, respectively), reflecting more peaked distributions than the normal curve.

|

Subdomain |

Mean |

SD |

SE |

Min |

Max |

Skew |

Kurtosis |

|

BCC |

78.90 |

13.40 |

0.20 |

16.67 |

100.00 |

-0.66 |

0.52 |

|

CC |

79.02 |

9.34 |

0.14 |

29.41 |

100.00 |

-0.82 |

1.54 |

|

HPM |

70.15 |

15.22 |

0.23 |

9.09 |

100.00 |

-0.48 |

0.24 |

|

PT |

71.41 |

15.53 |

0.23 |

6.25 |

100.00 |

-0.51 |

0.16 |

|

PA |

75.05 |

13.78 |

0.20 |

8.33 |

100.00 |

-0.46 |

0.19 |

|

PSI |

70.95 |

13.11 |

0.19 |

7.14 |

100.00 |

-0.39 |

0.14 |

|

RRP |

78.53 |

13.20 |

0.20 |

18.75 |

100.00 |

-0.78 |

0.82 |

|

SIC |

79.16 |

12.13 |

0.18 |

18.75 |

100.00 |

-0.69 |

0.66 |

|

CJ |

73.28 |

7.09 |

0.11 |

35.71 |

90.18 |

-0.78 |

1.44 |

Table 3: Descriptive Statistics of Manifest Variables.

Note: BCC = Basic Care and Comfort, Coordinated Care, CJ = Clinical Judgement, HPM = Health Promotion Maintenance, PA = Physiological Adaption, PHI = Physiological Integrity, PT = Pharmacological Therapies, PSI = Psychosocial Integrity, RRP = Reduction of Risk Potential, SEC = Safe and Effective Care Environment, SIC = Safety and Infection Control.

CFA Assumptions

There are two main statistical assumptions for CFA, multivariate normality and linearity. Multivariate normality was evaluated using Mahalanobis distance of 55.33 and a critical chi-square value of 27.88 (df = 9, α = 0.0001). Based on recommended thresholds for outliers the assumption of multivariate normality was reasonably met [9]. Linearity was evaluated using Pearson correlations and all variables demonstrated statistically significant positive correlations that ranged from r = 0.30 to r = 0.50 (p < 0.001). The correlations were generally moderate, indicating a strong relationship but measuring different aspects of nursing ability [10]. These patterns provide evidence of a linear factor structure and the discriminant validity of the exam (Table 4).

|

Variable |

BCC |

CC |

HPM |

PT |

PA |

PSI |

RRP |

SIC |

CJ |

|

BCC |

1.00*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CC |

0.35*** |

1.00*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HPM |

0.34*** |

0.41*** |

1.00*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PT |

0.37*** |

0.47*** |

0.49*** |

1.00*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PA |

0.31*** |

0.37*** |

0.38*** |

0.46*** |

1.00*** |

|

|

|

|

|

PSI |

0.30*** |

0.42*** |

0.36*** |

0.39*** |

0.31*** |

1.00*** |

|

|

|

|

RRP |

0.40*** |

0.46*** |

0.43*** |

0.52*** |

0.41*** |

0.36*** |

1.00*** |

|

|

|

SIC |

0.35*** |

0.48*** |

0.39*** |

0.48*** |

0.33*** |

0.39*** |

0.43*** |

1.00*** |

|

|

CJ |

0.36*** |

0.50*** |

0.39*** |

0.50*** |

0.37*** |

0.41*** |

0.48*** |

0.50*** |

1.00*** |

Table 4: Matrix Correlation Checking for Linearity Assumption.

Note: '***' indicate p-value < 0.001, BCC = Basic Care and Comfort, Coordinated Care, CJ = Clinical Judgement, HPM = Health Promotion Maintenance, PA = Physiological Adaption, PHI = Physiological Integrity, PT = Pharmacological Therapies, PSI = Psychosocial Integrity, RRP = Reduction of Risk Potential, SEC = Safe and Effective Care Environment, SIC = Safety and Infection Control.

Confirmatory Factor Model

Model Fit Metrics

To assess whether the PN CP aligns with the hypothesized confirmatory factor model, a goodness-of-fit analysis was conducted. Given the chi-square test’s sensitivity to large sample sizes, additional fit indices were evaluated, including the CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR [11,12]. Goodness of fit values are exhibiting good fit when CFI and TLI values exceed 0.95, SRMR is below 0.05 (with values up 0.08 still acceptable), and RMSEA is below 0.06 [11,13]. The goodness of fit values met or exceeded the cutoffs, with CFI (0.987) and TLI (0.982) exceeding the 0.95 benchmark, RMSEA at 0.038 (90% CI: 0.033–0.043) well below the 0.06 threshold, and SRMR at 0.018, comfortably under the 0.08 cutoff (Table 5). These results provide evidence that the model fits the data.

|

X2 |

df |

p-value |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA |

RMSEA CI Lower |

RMSEA CI Upper |

SRMR |

|

191.063 |

25 |

0 |

0.987 |

0.982 |

0.038 |

0.033 |

0.043 |

0.018 |

Table 5: Fit Measures of Confirmatory Factor Model.

Note: Recommended cut-off values for model fit indices in CFA:

- CFI (Comparative Fit Index) ≥ .90 (acceptable), ≥ .95 (excellent)

- TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) ≥ .90 (acceptable), ≥ .95 (excellent)

- RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) ≤ .08 (acceptable), ≤ .06 (excellent)

- SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) ≤ .08 (acceptable).

Parameter Loadings and Residuals

Factor loadings measure how strongly each observed variable (nine core content areas) is related to its underlying latent factor (nursing ability). They act like regression coefficients, showing how much an observed variable contributes to the latent factor. Higher loadings suggest stronger connections and a more significant role of the indicator in defining the factor. Typically, standardized loadings below 0.30 are seen as too weak for meaningful interpretation. According to Tabachnick and Fidell [14], factor loadings can be qualitatively evaluated as follows: values of 0.71 or above are deemed excellent, 0.63 as very good, 0.55 as good, 0.45 as fair, and 0.32 as poor.

In this model, the latent factor “Ability” demonstrates strong loadings: SEC (0.98), PHI (0.95), and CJ (0.71) were classified as excellent; HPM (0.62) was very good; and PSI (0.58) was good. The subfactor loadings were similarly robust. For example, SEC loads onto CC (0.70) and SIC (0.68), both considered very good. PHI loads onto PT (0.75, excellent), RRP (0.70, very good), PA (0.58, good), and BCC (0.54, fair).

These results suggest that the observed indicators were well-represented by their respective latent constructs. Additionally, residual variances were low for SEC (0.04) and PHI (0.10), indicating that most of the variance is explained by the model. Residuals for the remaining indicators fall within the expected range for CFA models See Figure 1.

Discussion

This study provided evidence supporting the PN CP as a valid tool for preparing students for NCLEX success and clinical practice. The results of this study provided insights into student performance and future research. The high average scores across assessment items, along with moderate to high variability, indicated that the students were generally well-prepared, though the variability suggests differing levels of mastery in various areas. The negative skewness and near-zero kurtosis for most items imply a trend toward higher scores, reflecting effective preparation and understanding, with Pharmacological Therapies (PT) showing a more pronounced peak, possibly indicating a more complex or challenging domain.

The multivariate normality assessment confirmed the dataset's suitability for CFA. The correlation analysis further supported the interconnectedness of clinical domains, with strong correlations among closely related areas and moderate correlations among distinct categories, reinforcing the assessment's discriminant validity. The goodness-of-fit analysis strongly supported the structural soundness of the proposed model, with all indices showing an excellent fit. This suggested that the PN CP exam was well-designed and effectively measured the latent construct it intended to capture. The high factor loadings across latent variables and subfactors demonstrated strong relationships between observed variables and their underlying constructs, confirming the assessment's validity. The low residual variances for certain factors, particularly SEC and PHI, merit further exploration. While they suggested that nearly all variance is explained by the latent factor, which is unusual, it may indicate potential overfitting or a need for model refinement.

Conclusion

While previous research focused on RN CP exams [5], this study demonstrated that the PN CP exam was well-aligned with the NCLEX test plan including clinical judgment. Consistent with RN research, the findings provided robust evidence of construct validity for the PN CP total score and sub-scores as meaningful indicators of entry-level nursing competence, which has implications for educational strategies and assessment practices in nursing education. The factor analysis indicated that nursing competence, as reflected in test performance, corresponded with domains such as a safe and effective care environment, psychosocial integrity, and clinical judgment. These domains aligned with the NCLEX test plan, underscoring their significance as dimensions of nursing ability. Given the alignment between the PN CP exam and the NCLEX test plan, educators can confidently use PN CP exam results to guide curriculum development, instructional methods, and remediation strategies. Future research could investigate how demographic diversity affects assessment outcomes and could explore the potential for customized educational interventions to address identified disparities.

References

- Health Resources and Services Administration (2025) Workforce projections.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor (2025) Occupational outlook handbook: Licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses. US Department of Labor.

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2025) 2024 PN practice analysis: Linking the NCLEX-RN.NCSBN Research Brief, 89.

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2025) Report of findings from the 2024 LPN/VN Nursing knowledge survey. NCSBN Research Brief, 91.

- Liu X, Mills C (2017) Assessing the construct congruence of the RN comprehensive predictor and NCLEX-RN test plan. Journal of Nursing Education, 56: 412-419.

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2023) 2023 PN test plan.

- Core Team R (2023) A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

- Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48: 1-36.

- Field A (2009) Discovering statistics using SPSS: Introducing statistical methods.

- Cohen J (1988) Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied psychological measurement, 12: 425-434.

- Byrne BM (2001) Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. International journal of testing, 1: 55-86.

- Schumacker RE, Lomax RG (2004) A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6: 1-55.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using multivariate statistics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Allyn & Bacon.

Citation: Hodge KJ, Miller JE, Lin Y, Yoo H, Phillips B (2026) Evaluating Construct Alignment of the PN Comprehensive Predictor and the NCLEX-PN Test Plan J Pract Prof Nurs 10: 066

Copyright: © 2026 Kari J. Hodge, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.