Green Transition in North Africa: Snapshot onthe Energy Changing Landscape in Tunisia and Morocco

*Corresponding Author(s):

Faten Attig BaharChair Of Wind Energy Technology, Faculty Of Mechanical Engineering And Marine Technology, University Of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

Tel::+49 172 398 25 57,

Email:faten.bahar@gmail.com and faten.attig-bahar@uni-rostock.de

Abstract

The transition from mainly fossil energy carriers to renewable energy is one of the megatrends of the 21st century. In this article, we present a critical review on the situation of two countries from North Africa: Tunisia and Morocco. Thus, we present the current scenarios for the energy transition, the legislative and regulatory framework adopted in recent years testifying both countries commitment to this energy transition. We also discuss some of the implications and opportunities, like impact on the economy and creation of jobs, coming together with renewables.

Keywords

Morocco; Renewable energy, Renewable energy framework;Tunisia

INTRODUCTION

The world's major concerns revolve around environment protection, clean and healthy production, climate change and wellbeing for the next generations. Energy and climate change and all the mentioned challenges are intrinsically linked, and what energy and the way we consume it,determines environmental impact. In order to avoid risks of global warming and climate change, which were the main topics in the Kyoto protocol and the conferences of the parties from COP21 to COP24, the use of renewable energy is regarded as an alternative. With improved technology and commercial affordability, Renewable Energy (RE) are in many countries in the plans for future energy supply. Renewable energy technologies, as presented in the recent review of Østergaard et al.,[1] have been intensively developed during the last two decades and ways to generate electricity from renewable technologies has been subject to several studies and investigations. For example, Dvo?ák et al.,[2] explored the relationship between the renewable energy investments and the job creation for the Czech Republic with reference to EU benchmarks. Their study explored how the biomass and waste energy processing offer the highest employment per MWh, which may benefit employment in rural areas. Chodkowska-Miszczuk et al.,[3] investigated the opportunities of the anaerobic digestion for biogas generation in the Czech Republic context. They assessed the anaerobic digestion importance for the local rural development and energy transition.

Moreover, there is a growing trend worldwide to invest in renewable energy as many countries commit to decreasing CO2 emissions from thermal plants. For non-resource rich countries, the motivation is to decrease energy costs by decreasing dependency on energy imports [4,5] since renewable energy has become an increasingly competitive way to meet new power generation needs [6]. In Africa, the renewable energy transition has been given a lot of attention since this transition will not only contribute to the climate issue and environment but also will abet the economic and social recovery [7,8].

Moreover, several case studies evaluating the impact and the importance of implementing renewables in different regions in North Africa have been conducted [9-12]. Maghreb countries have a significant global potential for renewable energy, and one of the largest solar energy potentials in the world in particular. In fact, Algeria has the highest solar potential in the Maghreb, followed by Libya and Tunisia, and Morocco has the highest wind potentials followed by Tunisia[12].

Since last two decades, Morocco and Tunisia, have committed themselves to the inclusion of green economic strategies in their national planning and strategies. In this paper, we present a snapshot on the changing energy landscape in both countries and present sustainable energy programs as well as the recent renewable energy regulatory framework, as both countries contributions toward climate mitigation.

METHODOLOGY

The aim of this paper is to provide a critical review of the renewable energy situation in both North Africa countries: Tunisia and Morocco. It is also, about presenting the legislative and the regulatory framework adopted in recent years testifying both countries commitment to this energy transition and discuss some of the implications and opportunities, such as the impact on the economy and creation of jobs. The source of data considered in this study are provided by official reports on renewable energy situation and plans in North Africa such as reports done by the United Nations (UN), the World Bank Group (WBG), the Africa Development Bank (AfDB), the International Agency of Renewable Energy(IRENA), the International Agency of Energy(IAE), official data available on the websites of WBG, IRENA and IEA and recent annual reports of the state-owned power utilities in Tunisia and Morocco. Finally, some review papers were considered for this purpose as well.

ENERGY SITUATION IN TUNISIA AND MOROCCO

Tunisia’s power sector is well developed, and nearly the entire population (99.8%) have access to the national electricity grid [13]. According to the state-owned power utility, the Tunisian National Company of Electricity and Gas (STEG) [13], in 2017, Tunisia has a power production capacity of 5,547 Megawatts (MW) installed in 25 power plants, which produced 19,252 gigawatt hours. The energy situation characterized by a heavy dependence on natural gas and oil. In fact this dependency on fossil energy reached 94% of the mix in 2017 [13]. Moreover, since 2000, the country has been a net energy importer due to increasing energy demand that exceeds national production as well as population growth and expansion of the economy [14].

Morocco’s energy profile is dominated by importing fossil fuels. It imports approximately 90% of its energy needs [15]. In 2015, the electrification rate in Morocco was 99% [16] and the power production capacity was 8,160 megawatts (MW), including coal (31%), hydroelectricity (22%), fuel oil (25%), natural gas (10%), wind (10%) and solar (2%) [16].The total primary energy consumption has increased by about 5 % per year since 2004. The energy demand has been driven by economic growth [17], an increasingly wealthier Moroccan population and the nation's industrial sector, which includes electricity-intensive activities like mining and car manufacturing[18] which has increased electricity access and contributed to rising demand.

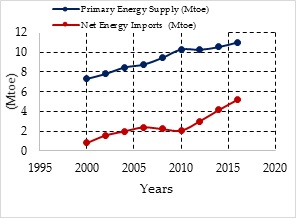

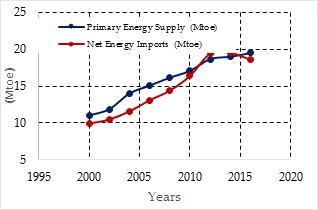

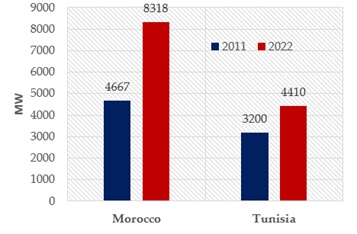

Figures 1,2 show the evolution of the primary energy supply and net energy import in in Tunisia and Morocco, respectively, between 2000 and 2016. From the curves, it is obvious that imports are increasing significantly from year to year. This dependency on energy imports makes both countries highly vulnerable to increases in international fuel prices, putting a heavy fiscal burden on the national budget. Figure 3[19] shows the evolution of installed power plants capacities in 2011 and the expected installed capacities in 2022 for both country [20]. For morocco is it about to increase the power generation by 44% and Tunisia is about to increase it by 27,5 %.

Figure 1: Primary energy supply and net energy imports in Tunisia between 2000 and 2016.

Figure 1: Primary energy supply and net energy imports in Tunisia between 2000 and 2016.

Figure 2: Primary energy supply and net energy imports in Morocco between 2000 and 2016.

Figure 2: Primary energy supply and net energy imports in Morocco between 2000 and 2016.

Figure 3: Evolution of installed/ expected installed capacities in Morocco and Tunisia between 2011-2022[19].

Figure 3: Evolution of installed/ expected installed capacities in Morocco and Tunisia between 2011-2022[19].

TUNISIAN CONTRIBUTION TOWARDS MITIGATION AND SUSTAINABLE ENERGY PROGRAMS

Regulatory framework

Tunisia is aware of the global warming challenges and fuel limitation resources and has worked since 1992 [21] to include adaptation to climate change in its development planning process at both the global and sectorial levels by offering opportunities to alternative pollution-free technologies for energy supply and make CO2 free energy system an energy-related policy priority of the government. Therefore, the Tunisian government initiated policies to promote the energy transition in its different phases by introducing investment aids for the realization of electricity production projects from renewable energy sources [22] and allowing any institution or group of establishments engaged in the industrial, agricultural or tertiary sectors to produce renewable power for their use. The law (N°74/2013)[23] gives producers the ability to sell up to 30% of the power generated to the Tunisian Company of Electricity and Gas (STEG) at a price equivalent to HT prices [24]. Additionally, the producers are allowed to use the national grid to transport power from the production plant to the consumer on payment of a transport fee. This fee was determined by the order of the Minister of Energy [24,25].

Furthermore, the Tunisian energy plan of 2030 deficits a progressive energy transition from the current conventional source of energy. This will be achieved through incremental diversification of the energy mix by promoting solar and wind power in particular[24]. Thus, the Tunisian authorities defined the four different “régimes” for renewable energy implementation, outlined by the 2015 law and 2016 decree [24], as follows:

- Large-scale projects, subject to concession (tender process)

- Small-scale projects, subject to authorization

- Self-production projects, subject to authorization

- Export projects, subject to concession.

Table1 summarizes the main actions considered by the Tunisian authorities toward mitigation and the promotion of the energy transition in the country [21,24,26-29].

|

Year |

Action |

Ref. |

|

1992 |

Tunisia signs the UNFCCC |

[21,28] |

|

2002 |

Portfolio of projects to reduce GHG emission. |

[24] |

|

2003 |

Tunisia Ratifies the KYOTO protocol. |

[21] |

|

2007 |

Air quality law. |

[24] |

|

2008 |

National Energy efficiency program. |

[24] |

|

2009 |

Tunisian Solar plan 2010/2016. |

[24] |

|

2010 |

Nationally appropriate mitigation plans |

[24] |

|

Since 2012 |

Preparation of new regulatory framework for RE (Electricity production) |

[24,29] |

|

2014 |

New constitution states climate must be protected. Under Article N°. 44 of the new constitution, the state shall “provide the means necessary to guarantee a healthy and balanced environment and contribute to climate’s integrity.” |

[24,29] |

|

2015 |

LawN°. 12: Electricity production from Renewable energy. |

[24,29] |

|

2016 (August) |

Decree N°.1123: Definition of conditions and procedures for implementing RE projects. October 2016: End of preparation of grid codes and contracts (currently under publication). |

[29] |

|

2017 |

Call for projects for 210 MW in May 2017. Publication of the official document on the technical requirements for connection and evacuation of energy produced from renewable energy installations connected to the low-voltage grid (all regimes). |

[29] |

|

2018 |

Authority acceleration plan for renewable energy implementation. |

|

|

Pre-qualification call for the concession regime for an RE capacity of 1700MW. |

|

|

|

Revision of the PPA and the MoP for the authorization regime and auto-production regime. |

[29] |

|

|

2019 |

Third round of calls for RE project for electricity production under the authorization regime. |

|

|

Announcement of the second round of projects for the electricity production from renewable energy (wind and solar PV) as part of the authorization regime. |

[29] |

Table 1: Tunisian commitment fighting against climate change and promoting renewable energy implementation.

Renewable energy projects

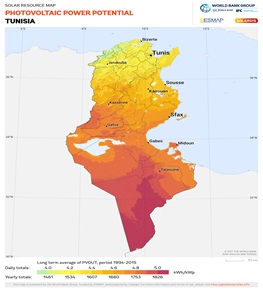

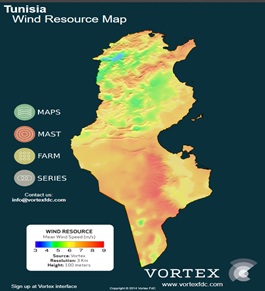

The location of Tunisia offers great opportunities to exploit the two main resources regarding renewable energy generation: solar and wind [11,12,19] in addition to some limited hydropower [30]. Solar energy potential in the country could by exploited to cater for the increased demand during the summer as a result of use of air conditioning. The lowest amount of direct sun irradiance is about 100 kW/m² during the months of December and January, while the maximum irradiance occurs in July; the wind resources provides a steady base load during the rest of the year[11,12,19]. The solar sources in Tunisia are estimated to 2kWh/m2/day in the Northern locations and to 6kWh/m2/day in the Southern locations and [11,19]the Northern and North Eastern region, together with the South Eastern regions have considerable wind capacity and the wind speed varies 7 and 8 m/s at 60 m above the sea level [11,19].Figures 4, 5 show both solar and wind maps in Tunisia.

Figure 4: Solar Map for Tunisia.

Figure 4: Solar Map for Tunisia.

Figure 5: Wind potential for Tunisia.

Figure 5: Wind potential for Tunisia.

Renewable energy generation in the Tunisian energy mix has been represented by both hydropower and wind energy. They contribute to 3 % of the energy mix in 2017 by producing 456 GWh[13].The STEG installed capacity of renewable energy at large scale is approximately equal to 302 MW (240 MW wind energy and 62 MW hydropower) in 2017.

In 2009, the government launched the Tunisian Solar Plan (TSP) which aimed to fund around 40 renewable projects, including 17 solar and 3 wind projects [31]. Those projects include:

- Solar rooftops within the PROSOL-ELEC program already in operation

- About 250 MW wind farms already in operation: (SidiDaoud farm (54MW), Bizerte farm stage (120MW), Bizerte farm stage (70MW)) and

- 250 MW to 300 MW in the pipeline within the EGCE Program and the SidiDaoud extension. However, there are no utility-scale investment in solar PV.

According to the Tunisian company of electricity and Gas ( SocieteTunisienne de l'Électricité et Gaz - STEG) [24], the planned installed renewable energy capacity by 2030 will be 3.815 MW including 1.755 MW of wind energy, 1.610 MW for solar Photovoltaic (PV), 100 MW of biomass and CSP 450 MW. Concerning the solar heating, Tunisia intends to triple the solar water heater distribution rate for more than 220 m² of collectors per 1,000 inhabitants in 2030, compared to 73 m² per habitant in 2015.

MOROCCO CONTRIBUTION TOWARDS MITIGATION AND SUSTAINABLE ENERGY PROGRAMS

Regulatory framework

Morocco made positive experiences with an energy reform program since the 1990s (“Programmed’ElecritificationRurale”) (PERG) [32], opening the energy market to private enterprises (Law no. 2-95-503 of 1994). The objective was to offer electricity to consumers at internationally competitive prices [12]. Moreover, Morocco's new constitution of 2011, included the right to sustainable development and basic services as well as the green growth and sustainable management of natural resources in the priorities of the current government program and political agenda[33]. This Framework law on Environment and Sustainable Development was approved in January 2013. Currently, the national strategic objective is to improve security of supply by reducing dependence on energy imports, including increasing use of renewable sources for electricity production and the main current renewable energy policies and targets can be summarized in the following points:

- The Moroccan authorities have targeted the objective, to have in 2020, 42% of overall electrical power capacity covered by renewable energy plants. Solar energy, wind energy, and hydropower will each represent 14%.

- he Moroccan authorities are allowing and facilitating the connection of public and private renewable energy producers to the medium, high and very high voltage national electricity grid (Law no. 13-09)[34].

- The Moroccan authorities are expediting the expansion of renewable energy by enabling producers who own a renewable energy project of less than 20 kW can connect to the medium, high and very-high voltage national grid without any condition and (13-09 Law).

The country has also established strategies to support renewable energy equipment manufacturing and among those strategies there are [35]: founding the Moroccan Association of Wind and Solar Industries (AMISOLE)[36]launched since 1987 in order to promote the interests of Moroccanprofessionals and industries involved in the sector of renewable energy (wind and solar), establishing the National Agency for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (ADEREE)[37] which provides training programs dedicated to the development of renewable energies and launching the Research Institute for Solar Energy and Renewable Energies (IRESEN)[38]which was created to bring together fundamental R&D and applied science at national level, to develop innovation and to encourage networking.

Table 2 presents the main actions considered by the Moroccan authorities toward mitigation and to promote renewable energy implementation.

|

Year |

Action |

Ref |

|

1987 |

Creation of the Moroccan Association of Wind and Solar Industries (AMISOLE) |

[36] |

|

2002 |

Morocco ratifies the KYOTO protocol. |

[39] |

|

2016 |

Morocco ratifies and sign the Paris agreement |

[39] |

|

2009 |

Renewable Energy Development (Law 13.09): Establishment of core regulation mechanisms for the production and commercialization of renewable energies. |

[40,41] |

|

2009 |

Creation of the National Agency for the Development of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency. |

[40,42] |

|

2009 |

[40] |

|

|

2009 |

[40,43] |

|

|

2008 |

Law of self-generation of power (Law 16.08): which means self-generation by industrial sites from 10MW to 50MW. |

[40] |

|

The Law was conceived principally to support wind power, but applies equally to other renewable energy technologies. |

||

|

2010 |

[40] |

|

|

2010 (last updated 2016) |

[40] |

|

|

Target new solar and wind capacities to meet the increasing energy demand in the country. |

||

|

2009 |

Creation of the Agency for the Development of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (Law 16-09) |

[40,44] |

|

2015 |

[40] |

|

|

Net-metering scheme for solar PV and onshore wind plants and only power plants connected to the high-voltage grid may participate. |

||

|

2015 |

[40] |

|

|

The 2009 National Energy Strategy set out an ambition for 42% of the total installed power capacity to come from renewable energy in 2020. |

||

|

In 2015, during the 21st session of the UNFCCC’s Conference of the Parties (COP21), Morocco announced a further planned increase in the renewables capacity to reach 52% of the total by 2030 (20% solar, 20% wind, 12% hydro). |

||

|

2009 |

[40] |

|

|

Includes a range of measures (mandatory energy audits, minimum energy performances standards for appliances and preferential tariffs (known as “super-peak” tariffs) for industries that voluntarily shift their energy consumption away from peak periods. |

Renewable energy projects

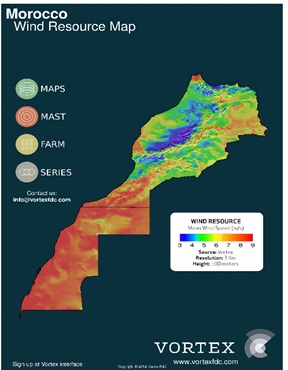

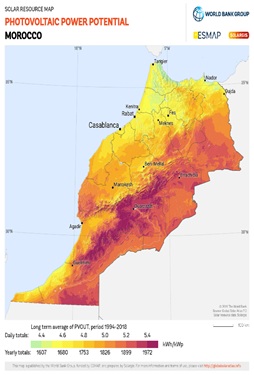

Morocco wind capacity is estimated at around 2500MW across it whole territory and around 6000 MW on some sites along the coastal areas and the country solar capacity is estimated to 20,000MW and with more than 3000hrs/year of sun shine and an irradiation of 5kw/m2/day [12]. Figures 6,7 show both wind and solar maps in Morocco.

Figure 6: Wind potential in Morocco.

Figure 6: Wind potential in Morocco.

Figure 7: Solar Map for Morocco.

Figure 7: Solar Map for Morocco.

Morocco is very advanced in terms of renewables energies compared Tunisia, in reason of its important energy import dependency [12,45]. In 2015, the energy installed capacity is about 32,1% of the total installed capacity and it included wind, solar, geothermal, hydro, counting 8,4 GW. Morocco announced a further planned increase in the renewables capacity to reach 52% of the total by 2030 (20% solar, 20% wind, 12% hydro) [12,45].

According to IRENA[35]the existing RE installations includes:

- The Ain BeniMathar plant, an hybrid natural gas associated with 20 MW of CSP is in operation.

- The Noor project, a 160 MW CSP plant, is currently in operation and additional 300 MW are in the pipeline.3. About 600 MW of wind energy are already in operation (Tarfaya, Tanger, Abdelkhalekorres).In particular, Tarfaya wind farm is the largest single farm in Africa. It reaches an overall capacity of 300 MW,15% of the 2020 national objective for wind capacity. The field works were completed in nearly 2014 and the plant is already fully operational since October 2014.

Figure 8 shows the planned capacity mix in Morocco in 2020 and 2030, as announced by the authorities.

Figure 8: Current and planned capacity mix in Morocco.

Figure 8: Current and planned capacity mix in Morocco.

DISCUSSION

It is obvious that Tunisia and Morocco have the potential to use their abundant natural renewable resources in order to ensure the energy security since the location of both countries offers the opportunity to exploit two main resources regarding renewable energy generation: solar and wind. Morocco and Tunisia are in advance, in term of the renewable energy plans and renewable energy installed capacities in comparison to their neighbors in the Maghreb region, Algeria and Libya. In fact, Despite of the rich endowment of renewable energy resources in Algeria and Libya [12,19,46], the installed base of renewable energy technology remains limited[12]. For Algeria, the installed capacity of renewable energy in 2015 was 250 MW (mainly hydro power) while for Libya it was 54 MW produced by two solar projects [12].

The development of renewable energy sector will have direct implications on the social and economic situation. In countries like Tunisia and Morocco the unemployment rates are increasing and estimated at 15.5% and 9.02% respectively in 2017 [47].In fact, RE projects are not expected to create a large number of direct jobs, because solar and wind energy production technology is capital-intensive rather than labor intensive. But RE has the potential to create an important number of indirect jobs in fields such as installation and maintenance activities, security of installations, research and development, teaching and training as well as manufacturing of some of the renewable energy installation components according to IRENA [35].Furthermore, by generating jobs, encouraging renewable energy entrepreneurship and market investment could go some way towards addressing unemployment. Increasing employment would not only mean a decrease in poverty, but also in crime, by decreasing income inequality [48].

Moreover, taking advantage of their strategic location open to the Mediterranean Sea and close to Europe both African countries can target neighboring European countries [12,45,49],since the European demand will increase over time, given the fact that the EU target is to reach 27% RE in its energy mix by 2030 [50]. Moreover, they can bring significant business and investment opportunities to Africa by supporting the manufacturing of renewable energy technologies and developing the associated knowledge and skills.

CONCLUSION

Taking advantage of rising energy prices, the abounded considerable renewable energy resources and the need to limit the independence of external energy, combined with the growing sensitivity in relation to environmental problems, renewable energies prove a necessity for sustainable development in both Tunisia and Morocco.Since last two decades, Morocco and Tunisia have committed themselves to the inclusion of green economic strategies in their national planning and strategies. For instance, the target of the Tunisian government is to achieve 30%renewables by 2030 while the goals in Morocco are to generate 42% of its electricity from renewable energies by 2020. Both the Tunisian and Moroccan energy strategy are decidedly towards sustainable development by integrating the promotion of renewable energy. The legislative and regulatory framework adopted in recent years testifies to this irreversible commitment.

Both Tunisia and Morocco can be considered as very dynamic and emerging markets and both showed serious commitment to the energy transition in the Maghreb region. However, further development of interconnected energy systems among the Maghreb countries, their African neighbors in the South and their European neighbors in the North can push forward the development of the national RE markets In an early phase, both countries can aim to produce RE energy to meet the internal needs, in the mid to long term they could target the neighboring markets and take advantage of privileged ties with these countries and their special location opening in the Mediterranean Sea. Besides, they could aim to benefit further from business opportunities related by developing the manufacturing of components and export them to the African continent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would also like to thank the Alexander von Humboldt foundation for providing the financial support for the study.

Any errors and oversights in this report are the sole responsibility of the authors.

REFERENCES

- Østergaard PA, Duic N, Noorollahi Y, Mikulcic H, Kalogirou S (2019)Sustainable development using renewable energy technology. Renew Energy 146: 2430-2437.

- Dvo?ák P,Martinát S, Horst DVD, Frantál B, Ture?kováK (2017) Renewable energy investment and job creation; a cross-sectoral assessment for the Czech Republic with reference to EU benchmarks. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 69: 360-368.

- Miszczuk JC, Martinat S, Cowell R(2019) Community tensions, participation, and local development: Factors affecting the spatial embeddedness of anaerobic digestion in Poland and the Czech Republic. Energy Res SocSci 55: 134-145.

- Mbarek MB, Saidi K, Rahman MM (2018) Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption, environmental degradation and economic growth in Tunisia. Qual Quant Int J Methodol 52: 1105-1119.

- World Energy Outlook (WEO) 2018, France.

- Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2018.

- Nathaniel SP,Iheonu CO (2019) Carbon dioxide abatement in Africa: The role of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption. Sci Total Environ 679: 337-345.

- WessehPK, Lin B (2016) Can African countries efficiently build their economies on renewable energy? Renew Sustain Energy Rev 54:161-173.

- Akuru UB, Onukwube IE, Okoro IO, Obe ES(2017) Towards 100% renewable energy in Nigeria. RenewSustain Energy Rev 71: 943-953.

- Aliyu AK,Modu B, Tan CW (2018) A review of renewable energy development in Africa: A focus in South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria. Renew Sustain Energy Rev81: 2502-2518.

- Hawila D, Mondal AH, Kennedy S, Mezher T(2014) Renewable energy readiness assessment for North African countries. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 33: 128-140.

- Schäfer I (2016) The Renewable Energy Sector and Youth Employment in Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. African Development Bank.

- STEG annual Report 2017, 2018.

- Key stats for Tunisia, 1990-2016.

- Ministere de l´ Énergie, des Mineset du Developpement durable- Marroc.

- Tarik Hamane (2015) A Snapshot of Morocco´s power sector in 2016 Africa Energy Yearbook, EnergyNet Ltd Pg no: 39-41.

- Morocco OverviewWorld Bank GroupWorld Bank.

- A D Bank, “Morocco Economic Outlook,” African Development Bank - Building today, a better Africa tomorrow, 27-Mar-2019.

- Bekaye M, Soltane KBB, Khennas S, Abbes R (2012) The Renewable Energy Sector in North Africa- Current Situation and Prospects.Subregional North Africa Office of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa(UNECA), Morocco.

- Arab Union of Electricity 2016.

- UNFCCC- Tunisia.

- Portail du Ministère de l’Industrieet des PMEs.

- Projet de loi N°74/2013 relatif à la production de l’électricité à partir des énergiesrenouvelables. Marsad

- Ministère de l’Energie, des Mineset des Energies Renouvelables de Tunisie.

- Tarifs du transport et de l’achat de l’excédent de l’autoproduction de l’électricité - STEG 2015.

- Bahar FA, Sahraoui M, Guellouz MS, Kaddeche S (2018) A Snapshot on the ChangingEnergyLandscape in Tunisiawith Relation to Climate Change and National Energy Situation. ENIT, Tunisia.

- Bahar FA, Sahraoui M, Guellouz MS, Kaddeche S (2018) Mapping a changing energy landscape in Tunisia with relation to climate change and national environmental policy. Presented at the 8TH GEWEX Open Science Conference: Extremes and Water on the Edge, Canmore, Canada.

- IEA - Tunisia- Policies and Measures for Renewable Energy.

- Ministère de l’Energie, des Mineset des Energies Renouvelables.

- Energy Profile: Tunisia United Nations Environment Programme (2017).

- O B Group, The Report: Tunisia 2009. Oxford Business Group.

- Electrification Rurale- Ministere de lÉnergie, des mineset du developpement durable.

- T W Bank (2014)Morocco - Country partnership strategy for the period FY2014-2017,” The World Bank.

- Law 13-09 on renewable energy, regulated by Decree 2-10-578,” Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment.

- Evaluating Renewable Energy Manufacturing Potential in the Mediterranean Partner Countries 2015, International Renewable Energy Agency.

- Amisole, Moroccan Association of Solar and Wind Industry, Kerix.net.

- Aderee(National Agency For The Development Of Renewable Energy And Energy Efficiency)

- IRESEN-Institut de RechercheenEnergieSolaireet Energies Nouvelles.

- Morocco | UNFCCC.

- IEA - Morocco- Policies and Measures for Renewable Energy.

- Loi n°13-09.

- Loi n°16-09. Ecolecx, Moroco.

- loi n°57-09.

- ADEREE - L’AgenceNationale pour le Développement des Energies Renouvelableset de l’EfficacitéEnergéti

- Kousksou T, Allouhi A, Belattar M, Jamil A, RhafikiTEl, et al.(2015) Renewable energy potential and national policy directions for sustainable development in Morocco. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 47:46-57.

- Ghezloun A, Saidane A,Oucher N, Merabet H (2015) Actual Case of Energy Strategy In Algeria and Tunisia. Energy Procedia74: 1561-1570.

- Global economy, world economy, TheGlobalEconomy.com.

- Fajnzylber P, Lederman D (2002) Inequality and violent crime. J Law Econ45:Pg no. 40.

- Benasla M, Hess D, Allaoui T, Brahami M, DenaïM, (2019) The transition towards a sustainable energy system in Europe: What role can North Africa’s solar resources play? Energy Strategy Rev 24: 1-13.

- Global energy transformation: A Roadmap to 2050.Pg no 76.

Citation: Bahar FA, Allali A,RitschelU, Akari P (2019) Green Transition in North Africa: Snapshot on the Energy Changing Landscape in Tunisia and Morocco. J Atmos Earth Sci 3: 013.

Copyright: © 2019 Faten Attig Bahar, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.