Journal of Pulmonary Medicine & Respiratory Research Category: Medical

Type: Case Report

Increased FDG-PET Uptake in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature

*Corresponding Author(s):

Rama El-YafawiDepartments Of Pulmonary And Critical Care Medicine, Maine Medical Center, Portland, United States

Tel:+1 3473797802,

Email:RElYafawi@mmc.org

Received Date: May 09, 2018

Accepted Date: Jun 08, 2018

Published Date: Jun 22, 2018

Abstract

In this study, high binding efficiency for immobilization of pectin lyase was obtained using chitosan beads. Formaldehyde at a concentration of 10% (v/v) was used as a cross-linking agent. Further, characterization of free and immobilized pectin lyase was carried out to compare their physico-chemical properties. The optimal conditions for activity of free pectin lyase were found to be: glycine-NaOH buffer (50 mM), pH 10.0, incubation time 15 min and reaction temperature 40?C and for immobilized enzyme: glycine-NaOH buffer (50 mM), pH 10.0, incubation time 15 min and reaction temperature of 50?C. Pectin lyase showed maximum enzyme activity in the presence of Mg2+ ions for both free and immobilized enzyme. Chitosan bead-bound pectin lyase showed 83% binding efficiency. Immobilized pectin lyase retained almost 50% of its original activity up to 4th cycle. The obtained bio-conjugate showed increased optimum temperature and improved thermostability. These properties support the potential application of the immobilized pectin lyase in the pulp industries.

Case description

A 70-year-old woman presented with a large RLL mass (5×4 cm), which showed intense uptake on 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) Positron Emission Tomography (PET). Additionally, multiple lymph nodes showed increased radiotracer uptake. Cervical mediastinoscopy was non-diagnostic. CT-guided biopsy of the RLL mass showed only necrotic tissue. Subsequently, she developed acute renal failure and renal biopsy was consistent with severe crescentic glomerulonephritis, pauci-immune type. C-ANCA titers were markedly positive with ELISA confirming antibodies to anti-proteinase-3. Diagnosis of GPA was made. Treatment consisted of plasmapheresis, steroids, rituximab, cyclophosphamide and hemodialysis. At 3 months, sufficient renal function noted to discontinue hemodialysis with decreasing ANCA titers and RLL mass size. At 1 year, ANCA titers were negative and RLL mass resolved.

Discussion

Although rare, GPA may present with a FDG-avid solitary pulmonary mass and mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes, mimicking malignancy. This can result in a delay in diagnosis and treatment; therefore, a broad differential diagnosis is always imperative to avoid early closure. FDG-PET may have a role in diagnosis and management of GPA but further studies are needed.

ABBREVIATIONS

ANCA: Antinuetrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody

c-ANCA: Cytoplasmic-Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody

CT: Computed Tomography

GPA: Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

PET: Positive Emission Tomography

RLL: Right Lower Lobe

c-ANCA: Cytoplasmic-Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody

CT: Computed Tomography

GPA: Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

PET: Positive Emission Tomography

RLL: Right Lower Lobe

INTRODUCTION

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA) is the most common of the ANCA-associated vasculitides, and most commonly involves kidneys as well as upper and lower respiratory tract [1]. The clinical triad is characterized by upper airway involvement (e.g., sinusitis, otitis, ulcerations), lower respiratory involvement (e.g., cough, chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis), and glomerulonephritis; however, up to 22% of patients may have disease limited to the respiratory tract [2-4]. Pulmonary involvement occurs in 70-95% of patients with GPA; most commonly presenting as Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage (DAH), reported in 5-45% of cases [1,5]. Tracheobronchial and endobronchial disease is not uncommon and occurs in 10-15% of cases [2]. Hilar adenopathy and mediastinal masses are exceedingly rare in patients with GPA. There are no estimates of the prevalence of these findings; however, a retrospective study with 302 patients reported a frequency of 2% [6]. We describe an unusual case of GPA presenting with a large PET-positive right lower lobe mass and mediastinal adenopathy.

CASE REPORT

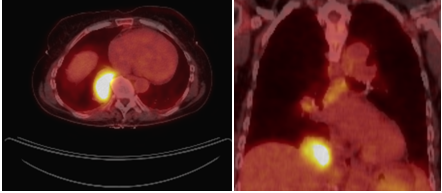

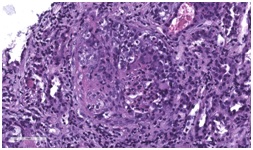

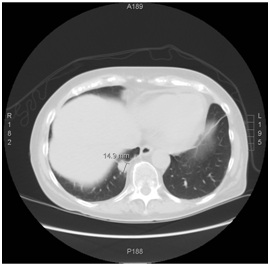

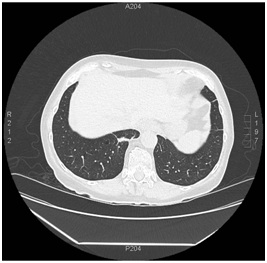

A 70-year-old woman with a distant 10 pack-year smoking history, presented with right shoulder pain, associated with mild pleuritic chest pain. She denied cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis and constitutional symptoms. Vital signs were normal and physical exam was unremarkable. Laboratory data, including blood nitrogen urea and creatinine, were within normal limits. She reported recent air travel, and concern was raised for pulmonary embolism. Chest CT showed a Right Lower Lobe (RLL) mass measuring approximately 5×4 cm (Figure 1). PET scan displayed intense radiotracer uptake in the mass with maximum SUV measured at 13.1 (Figure 2a). Additionally, there was increased uptake in a subcarinal lymph node and multiple right hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes (Figure 2b), with a maximum SUV of 4.5. Given a high suspicion for malignancy, she underwent mediastinoscopy. Bulky adenopathy was identified; biopsies were benign with no evidence of malignancy or granulomata. Flow cytometry was negative. Given the lack of a diagnosis, CT-guided biopsy of the mass was pursued. Sections demonstrated fragments of necrotic tissue with negative cultures. Due to continued concern for malignancy, video-assisted thoracic surgery was scheduled. Pre-operative laboratory evaluation revealed a creatinine of 2.4 mg/dL (baseline 0.6 mg/dL); this was thought to be due to contrast used for the CT-guided biopsy. Four days later, a repeat creatinine was 5.7 mg/dL; surgery was deferred and she was admitted for evaluation of acute kidney injury. Urine microscopy demonstrated proteinuria, hematuria with dysmorphic RBCS and RBC casts, consistent with acute glomerulonephritis. Based on the presentation and urine sediment, empiric treatment was initiated with pulse steroids. Unfortunately, rapid deterioration in renal function ensued, prompting initiation of plasmapheresis and hemodialysis. Renal biopsy was performed (Figures 3 and 4) revealing severe crescentic glomerulonephritis with active cellular crescents involving 90% of the viable glomeruli. Electron microscopy was pauci-immune. C-ANCA positivity was significantly elevated at 11,469 units with ELISA confirmation of antibodies to anti-proteinase 3. Based on the classic findings of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis on renal biopsy as well as the markedly positive C-ANCA titers, the diagnosis of GPA was made. Therapy was initiated with methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days followed by prednisone 60 mg daily, weekly rituximab for 4 weeks, cyclophosphamide 100 mg daily for 7 days followed by 50 mg daily for 7 weeks and 6 sessions of plasmapheresis. Given renal failure, hemodialysis was simultaneously started. Three weeks after initiation of therapy, repeat ANCA titers decreased to 819 units. She remained dialysis dependent for 3 months until sufficient renal functional return was noted and dialysis was discontinued. Chest CT at 3 months (Figure 5) showed reduction in the size of the mass to 1.5 cm in diameter. Immunotherapy was continued. At one year, repeat ANCA titers were negative at 1.4 units and the RLL mass resolved (Figure 6).

Figure 1: Chest CT scan showing RLL mass (4×5 cm).

Figure 1: Chest CT scan showing RLL mass (4×5 cm). Figure 2: PET scan showing increased FDG uptake of a) RLL mass and b) mediastinal lymph nodes.

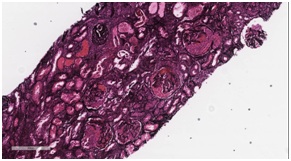

Figure 2: PET scan showing increased FDG uptake of a) RLL mass and b) mediastinal lymph nodes. Figure 3: Light microscopy of renal biopsy using Hematoxylin and Eosin stain (H&E stain) showing activecellular crescents within the glomerulus.

Figure 3: Light microscopy of renal biopsy using Hematoxylin and Eosin stain (H&E stain) showing activecellular crescents within the glomerulus. Figure 4: Jones basement membrane stain showing extensive crescentic changes and fibrosis.

Figure 4: Jones basement membrane stain showing extensive crescentic changes and fibrosis. Figure 5: Three month follow up chest CT, showing reduction in mass size.

Figure 5: Three month follow up chest CT, showing reduction in mass size. Figure 6: One year follow up chest CT, showing resolution of RLL mass with remnant pleural parenchymal scarring.

Figure 6: One year follow up chest CT, showing resolution of RLL mass with remnant pleural parenchymal scarring.DISCUSSION

Granulomatosis with polyangiitisis small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the kidneys, upper and lower respiratory tracts [7]. Approximately 85% of patients develop pulmonary manifestations [6]. Lower airway abnormalities can be found in up to half of GPA patients; including subglottic stenosis, ulcerating tracheobronchitis and tracheal or bronchial stenosis [8]. DAH due to alveolar capillaritis is a prominent feature of pulmonary involvement, reported in 5-45% of cases [5]. Unilateral pleural effusion has been reported in up to 12.4% of patients [9]. Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is quite rare. There have only been ten reported cases of GPA with hilar or mediastinal adenopathy [10-13].

Pulmonary nodules and masses are common radiologic findings and increased FDG activity has been reported in patients with GPA; median SUVmax has generally been reported within a range of 7.6-9, as compared to our patient, who had an SUVmax of 13.1 [14,15].

Despite its limitation in differentiating inflammatory diseases from malignancies, FDG-PET/CT may have a role in early diagnosis of GPA. In certain patients, it can provide valuable guidance for optimal biopsy site, localization of organ involvement and characterization of disease severity, which could have treatment implications [14-17]. Furthermore, a case series reported a remarkable decrease in FDG uptake with treatment [17]. This indicates that FDG uptake correlates with disease activity in GPA.

This case demonstrates an unusual radiographic presentation of GPA, with findings initially concerning primarily for malignancy, particularly related to the observed increased FDG uptake in mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. This resulted in a delay in the diagnosis of GPA, which became evident only with development of acute kidney injury with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Despite this delay, clinical response was achieved with corticosteroids, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis and hemodialysis, with recovery of renal function, resolution of CT imaging and normalization of c-ANCA titers.

Pulmonary nodules and masses are common radiologic findings and increased FDG activity has been reported in patients with GPA; median SUVmax has generally been reported within a range of 7.6-9, as compared to our patient, who had an SUVmax of 13.1 [14,15].

Despite its limitation in differentiating inflammatory diseases from malignancies, FDG-PET/CT may have a role in early diagnosis of GPA. In certain patients, it can provide valuable guidance for optimal biopsy site, localization of organ involvement and characterization of disease severity, which could have treatment implications [14-17]. Furthermore, a case series reported a remarkable decrease in FDG uptake with treatment [17]. This indicates that FDG uptake correlates with disease activity in GPA.

This case demonstrates an unusual radiographic presentation of GPA, with findings initially concerning primarily for malignancy, particularly related to the observed increased FDG uptake in mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. This resulted in a delay in the diagnosis of GPA, which became evident only with development of acute kidney injury with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Despite this delay, clinical response was achieved with corticosteroids, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis and hemodialysis, with recovery of renal function, resolution of CT imaging and normalization of c-ANCA titers.

REFERENCES

- Frankel SK, Cosgrove GP, Fischer A, Meehan RT, Brown KK (2006) Update in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary vasculitis. Chest 129: 452-465.

- Anderson G, Coles ET, Crane M, Douglas AC, Gibbs AR, et al. (1992) Wegener's granuloma. A series of 265 british cases seen between 1975 and 1985. A report by a sub-committee of the british thoracic society research committee. Q J Med 83: 427-438.

- Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, Loire R, Brechot JM (1990) Pulmonary Wegener's granulomatosis. A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest 97: 906-912.

- Frankel SK, Sullivan EJ, Brown KK (2002) Vasculitis: Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, microscopic polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, and Takayasu arteritis. Crit Care Clin 18: 855-879.

- Schwarz M, Brown K (2000) Small vessel vasculitis of the lung. Thorax 55: 502-510.

- George TM, Cash JM, Farver C, Sneller M, van Dyke CW, et al. (1997) Mediastinal mass and hilar adenopathy: Rare thoracic manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum 40: 1992-1997.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, et al. (2013) 2012 revised international chapel hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 65: 1-11.

- Daum TE, Specks U, Colby TV, Edell ES, Brutinel MW, et al. (1995) Tracheobronchial involvement in Wegener's granulomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151: 522-526.

- Bambery P, Sakhuja V, Behera D, Deodhar SD (1991) Pleural effusions in Wegener's granulomatosis: Report of five patients and a brief review of the literature. Scand J Rheumatol 20: 445-447.

- Boudes P (1990) Mediastinal tumour as the presenting manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis. J Intern Med 227: 215-217.

- Gutiérrez-Ravé VM, Ayerza MA (1991) Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy in the limited form of Wegener's granulomatosis. Thorax 46: 219-220.

- Hashizume T, Yamaguchi T, Matsushita K (2002) Supraclavicular and axillary lymphadenopathy as the initial manifestation in Wegener's granulomatosis. Clin Rheumatol 21: 525-527.

- Papiris SA, Manoussakis MN, Drosos AA, Kontogiannis D, Constantopoulos SH, et al. (1992) Imaging of thoracic Wegener's granulomatosis: The computed tomographic appearance. Am J Med 93: 529-536.

- Nelson DR, Johnson GB, Cartin-Ceba R, Specks U (2016) Characterization of F-18 Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 32: 342-352.

- Soussan M, Abisror N, Abad S, Nunes H, Terrier B, et al. (2014) FDG-PET/CT in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis: Case-series and literature review. Autoimmun Rev 13: 125-131.

- Almuhaideb A, Syed R, Iordanidou L, Saad Z, Bomanji J (2011) Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT rare finding of a unique multiorgan involvement of Wegener's granulomatosis. Br J Radiol 84: 202-204.

- Ueda N, Inoue Y, Himeji D, Shimao Y, Oryoji K, et al. (2010) Wegener's granulomatosis detected initially by integrated 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Mod Rheumatol 20: 205-209.

Citation: El-Yafawi R, Van der Kloot TE, Cantlin P (2018) Increased FDG-PET Uptake in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Pulm Med Respir Res 4: 016.

Copyright: © 2018 Rama El-Yafawi, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!