Marijuana Use among College Students after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Classification and Regression Tree Approach

*Corresponding Author(s):

Sung Seek MoonDiana R. Garland School Of Social Work, Baylor University, Waco, Texas 76798, United States

Tel:+1 8172285897,

Email:Sungseek_Moon@Baylor.edu

Abstract

Marijuana is one of the most frequently used substances among young adults, and its use among college students has been increasing since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociodemographic and mental health correlates of marijuana use in this population are complex and not well understood. Using a decision tree analysis, we examined correlates of marijuana use in a sample of 835 U.S. college students to classify how the factors relate to one another during the COVID-19. The results presented the six most important factors of marijuana use in descending order: 1) electronic vapor product, 2) current alcohol use, 3) stress, 4) race and ethnicity, 5) loneliness and 6) COVID-19 protective behaviors. These findings can inform current responses to prevent and treat substance use among college students.

Keywords

COVID-19 protective behaviors; Marijuana; Substance use; University students; Vaping

Marijuana Use Among College Students After The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Classification And Regression Tree Modeling

The use of marijuana and other substances among college students remains a concern because of the association with negative outcomes (e.g., depression; anxiety) regardless of whether the substances are used simultaneously or concurrently [1]. Wedel [2] has reported that marijuana use among college students has dramatically increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies have examined several factors related to increased marijuana use, including limited social contact, distress and uncertainty [2-4]. Also, other factors such as sociodemographic variables and other substance uses are associated with marijuana use [1,5,6], which makes it imperative to identify marijuana use risk factors to understand this phenomenon.

While numerous studies have explored the relationship between marijuana use and its risk factors among college students after the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a gap in the literature concerning the investigation of how these factors interact and relate to each other through classification. To date, no studies have been conducted to examine the interplay and categorization of these risk factors systematically. Specifically, existing research has predominantly focused on examining individual risk factors in isolation without considering their potential interactions or the broader classification of these factors into meaningful groups or categories. Understanding how these factors interact and relate can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics of marijuana use among college students in the post-COVID-19 context. By conducting a classification analysis, researchers can identify distinct patterns or profiles of risk factors associated with different levels or patterns of marijuana use. This deeper level of analysis can enhance our understanding of the multifaceted nature of marijuana use among college students and inform the development of targeted interventions and prevention strategies. According to De’ath and Fabricius [7], “Regression trees can be used for interactive exploration and for description and prediction of patterns and processes” (p. 3178) that may not have been revealed through common linear regression techniques, which makes it a useful analytic technique in the process of examining marijuana use among college students in the United States.

- Socio-demographic variables and marijuana use

Various socio-demographic variables have been identified as factors associated with marijuana and substance use among college students. These variables include living arrangements (on-campus vs. off-campus), participation in Greek life, age, gender, race/ethnicity and mental illness [8-10]. For instance, research by Jackson et al., [1] found that concurrent use of marijuana and alcohol was more prevalent among non-white and Hispanic students.

Furthermore, Pro et al., [11] examined the influence of microaggressions on marijuana use among minority college students. They found that experiencing microaggressions increased stress levels, and marijuana was often used as a coping mechanism. Each experience of microaggressions was associated with higher marijuana use, highlighting how some minority students use marijuana to manage distressing social and relational problems. Gender differences in marijuana use have also been observed. White et al., [10] noted that males were more likely than females to engage in concurrent marijuana and alcohol use. Additionally, Casey and Cservenka [5] found that females reported initiating marijuana use at a younger age than males.

- Mental health, stress and marijuana use

Several studies have found a positive association between anxiety and marijuana use among college students. For example, Buckner, Heimberg, and Matthews [12] found that individuals with social anxiety disorder were more likely to use marijuana to cope with their anxiety symptoms. Similarly, Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky and Bernstein [13] observed that individuals with elevated anxiety symptoms reported higher rates of marijuana use. Depression has also been identified as a potential predictor of marijuana use among college students. A study by Lev-Ran, Roerecke, Le Foll, George, and McKenzie [14] found a significant association between depression and marijuana use among college students. They suggested that individuals with depression may turn to marijuana as a form of self-medication or to alleviate depressive symptoms. It is important to note that the relationship between mental health and marijuana use is complex and can be bidirectional. While some individuals may use marijuana to cope with symptoms of anxiety or depression, marijuana use can also potentially contribute to or worsen mental health problems in susceptible individuals [13].

The association between stress and marijuana use among college students has been a topic of interest in recent research. A study by Buckner, Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, and Schmidt [15] found that higher levels of perceived stress were associated with increased marijuana use among college students. They suggested that individuals may use marijuana as a coping mechanism to alleviate stress and manage negative emotions. Similarly, Lee, Neighbors, and Woods [16] investigated the role of perceived stress and coping motives in marijuana use among college students. They found that higher levels of perceived stress were associated with greater coping motives for marijuana use. This suggests that individuals may turn to marijuana to cope with life stressors. Furthermore, research by Ham, Hope, and College Drinking Prevention Research Team [17] indicated that perceived stress was positively associated with marijuana use among college students. They suggested that individuals may use marijuana to relax and unwind, particularly in response to high-stress levels. However, it is essential to note that the relationship between stress and marijuana use is complex and bidirectional. While some individuals may use marijuana as a coping mechanism, others may experience increased stress levels due to the negative consequences or conflicts associated with marijuana use [15].

- Substance use and marijuana use

Pro et al., [11] found that “College student substance use is associated with reduced achievement, decreased retention and lower postcollege employment” (p?). . In general, college students were found to use substances such as marijuana, tobacco, vaping substances and alcohol [1,10,18]. A study by Gunn et al., [6] found that the order that which one consumes alcohol and/or marijuana plays an important role in the rate of consumption, using alcohol first on days that both substances are consumed, contributes to more drinking, even though consuming alcohol typically occurs later in the day [6]. Another aspect of the usage of substances had directly correlated with college student driving under the influence with marijuana and alcohol simultaneously being a high percentage of 36 compared to 5 percent with only those consuming alcohol [1,19].

A study that followed college students over four semesters found that those who used both alcohol and marijuana had lower grades compared their peers [18]. However, students who moderate their use of substances improved their academic performance compared to those who remained with the same amount of usage [18]. Gunn et al., [6] found that being at a friend’s house made individuals more likely to use marijuana and alcohol together compared to alcohol-only and cannabis-only. The presence of being at a “social event in [a] private setting”, such as at a friend’s house, increases the simultaneous use of substances.

- COVID-19 preventive behavior and marijuana use

Firkey, Sheinfil, and Woolf-King [20] found that 73.2 percent of their participants reported following the CDC guidelines of physical distancing. Of this percentage of respondents practicing protocols 72% reported lower levels of wellbeing and 64% reported higher anxiety levels. Regarding the use of marijuana during the pandemic 15% increased use, 26% decreased use and most (58%) had no change [20]. Pandemic related adjustment appear to be impacting substance use and social support. Even students with high exposure to news related to the COVID-19 pandemic had increased vaping and tobacco use [21]. College students engaging in the social distancing protocol report decreased social support and increased use of alcohol as time passed during the pandemic [4].

Methods

Study design and sample

Between July and August 2020, in collaboration with five researchers across five universities, we collected cross-sectional data from public and private universities in the United States via an online survey. We employed a nonprobability sampling approach to recruit undergraduate and graduate students aged 18 years and older who were enrolled at colleges and universities in the U.S. during the 2020 summer semester. The research team distributed a link to the online survey that was hosted on a Qualtrics platform using the email listservs of students who attended their programs. The team also collaborated with course instructors of the 2020 summer semester programs and asked them to share the survey link with their students.

Two weeks after the initial distribution of the survey link, reminders to complete the online survey were sent to all students who had been initially contacted with the survey link. Participation in the online survey was voluntary. No incentives were offered for completing the survey, which took about 20-30 minutes to complete. After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval had been obtained at the host study site, IRB approvals of the remaining four universities were relinquished to the host institution in line with the IRB reliance agreement approvals from the four universities.

The survey was completed by 855 college students attending universities across the United States. Participants represented a diverse range of institutions, with the largest proportion (34.4%) attending a southwest university. Additionally, two universities located in the South contributed 27.0% and 9.0% of the sample, respectively, while two Midwest institutions accounted for 14.9% and 9.0% of the responses. The remaining 5.7% of participants were from other universities scattered across the U.S. Regarding handling missing data, we adopted a listwise deletion approach. As a result, the sample sizes varied between bivariate and multivariate analyses due to participants omitting responses to specific survey questions. While listwise deletion can lead to reduced sample sizes and potential loss of information, we considered this method appropriate for our analysis, given its simplicity and ability to provide valid estimates under the assumption that data are missing completely at random.

We used the terms “Hispanic,” “Latino,” and ”Latinx” interchangeably in the current study because they are often used in research and discussions to describe individuals of Latin American or Spanish origin or descent. While these terms are used to refer to similar populations, they may have different historical, cultural, and linguistic connotations. We decided to use these terms interchangeably in our manuscript to ensure inclusivity and recognize the diversity and complexity of the populations we are studying.

Measures

The selected variables, derived from a comprehensive literature review, were measured using the following instruments:

- Marijuana use

Marijuana use was originally assessed on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = 0 times, 2 = 1 or 2 times, 3 = 3 to 9 times, 4 = 10 to 19 times, 5 = 20 to 39 times, 6 = 40 or more times). This variable was changed to a binary form for the current study (0 = never used, 1 = used). As a cross-sectional study, our research focused on obtaining a snapshot of marijuana use among participants at a specific point in time. The survey questions were designed to capture information on marijuana use within the past year without specifying distinct measurement intervals.

- Sociodemographic variables

The current study had nine sociodemographic variables: age, sex, race/ethnicity, GPA, marital status, hours worked per week, living with children, loss of employment during the COVID-19 pandemic, and living arrangements.

- Mental health variables and substance use

Anxiety: The seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., [22]) was used to assess anxiety levels among participants. The self-administered GAD-7 scale assesses the frequency of anxiety symptoms in both clinical and research settings. For response options, GAD-7 uses a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (nearly every day). Anxiety can be rated as mild (5 points), moderate (10 points), moderately severe (15 points), and severe (20 points), with 10 points being the threshold for a diagnosis of anxiety [22]. All items were summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety. Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 in our sample.

Depression: The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., [23]) was used to assess depressive symptoms among the respondents. The nine-item self-administered PHQ-9 uses a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (nearly every day). Depression can be rated as mild (5 points), moderate (10 points), moderately severe (15 points), and severe (20 points), with 10 points being the threshold for a diagnosis of depression [23]. All items were summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depressive symptoms. Cronbach's alpha was 0.87 in our sample.

Stress: The 11-item College Student Stress Scale [24] was used to measure perceived stress frequently experienced by university students. Respondents rated the frequency with which they experience anxiety or distress because of the 11 listed events (e.g., financial matters; academic matters) using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). All items were summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of stress. Cronbach's alpha was 0.83 in our sample.

Self-harming thoughts: To measure the frequency of self-harming thoughts, we asked the following question: “How often have you had thoughts about harming yourself during the COVID-19 pandemic?” This question was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Higher scores indicate more frequent occurrences of self-harming thoughts.

Substance Use (SU) variables: Alcohol, tobacco, EVP (Electronic Vapor Products) use were originally assessed on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = 0 times, 2 = 1 or 2 times, 3 = 3 to 9 times, 4 = 10 to 19 times, 5 = 20 to 39 times, 6 = 40 or more times). Variables were dichotomized to indicate any use (0 = never used and 1 = used) of each variable. As a cross-sectional survey, we focused on obtaining a snapshot of substance uses within the past year, without specifying distinct measurement intervals.

- COVID-19 Protective Behaviors (CPB)

CPBs were measured using six items: 1) Wash hands more; 2) Exercise; 3) Wear a mask; 4) Eat nutrition food; 5) Practice social distancing; and 6) Get a good night’s sleep. Each item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often and 4 = always. All items were summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of CPB. Cronbach's alpha was 0.87 in our sample.

- Data analysis

We began the analysis by providing descriptive statistics for all variables included in the study. Continuous variables, such as age and frequency of substance use, were summarized using means and standard deviations. Categorical variables, such as gender, race/ethnicity, and living arrangements, were presented as frequencies and percentages.

- Bivariate analysis

We conducted bivariate analyses to explore the relationships between marijuana use and individual predictors. Chi-square tests were employed for categorical predictors, examining the associations between marijuana use and variables such as gender, race/ethnicity, participation in Greek life, and COVID-19 protective behaviors. For continuous predictors, such as age and psychological factors, t-tests were conducted to assess the differences in marijuana use among different subgroups.

Classification and Regression Trees (CART) analysis

To identify significant predictors of marijuana use among college students, we applied Classification and Regression Trees (CART) analysis. CART is a data-driven, non-parametric technique that recursively partitions the data based on predictor variables to form distinct subgroups with similar outcomes. The primary outcome variable in the CART analysis was marijuana use, and the predictors considered included substance use, psychological factors, COVID-19 protective behaviors, and sociodemographic characteristics. The tree-growing process involved evaluating multiple splits based on the predictors' significance in predicting marijuana use. We employed cross-validation techniques to assess the model's predictive accuracy and identify the most parsimonious tree with the optimal number of splits. All data analyses were conducted using Minitab Salford Predictive Modeler (2019), and a significance level of 0.05 was used for all inferential tests.

Results

This study found that the prevalence of marijuana use was 19.5%. The mean age of participants was 28.6 years (SD = 8.84). Among the participants, 81.6% were female, 64.4% were White, and 25.7% were living with their children. 62.1% of the study participants were single or never married, 50.2% were living with family, 19.4% had lost a job during the COVID-19 pandemic, 21.4% were working 11-20 hours per week, and 50.2% of them had a current GPA between 3.5 and 4.0 (Table 1).

|

Sociodemographic Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Age 18-25 26-30 31-35 36-40 41 or older Total |

400 183 96 59 95 833 |

48.0 22.0 11.5 7.1 11.4 100 |

|

Gender Male Female Other Total |

147 681 7 835 |

17.6 81.6 0.8 100 |

|

Race/Ethnicity White Black/African Americans Hispanic/Latino Asian American Indian/Alaska Native Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander Other Total |

538 77 83 100 6 1 30 835 |

64.4 9.2 9.9 12.0 0.7 0.1 3.6 100 |

|

GPA 2.0-2.49 2.5-2.99 3.0-3.49 3.5-3.99 4.0 or over Total |

4 27 125 416 256 828 |

0.5 3.3 15.1 50.2 30.9 100 |

|

Marital Status Single/Never married Married Cohabitation Divorced Separated Widowed Other Total |

518 212 45 38 4 4 13 834 |

62.1 25.4 5.4 4.6 0.5 0.5 1.6 100 |

|

Working hours per week No job 10 hours or less 11-20 hours 21-30 hours 31-40 hours More than 41 hours Total |

222 87 179 75 166 106 835 |

26.6 10.4 21.4 9.0 19.9 12.7 100 |

|

Living with Children No Yes Total |

620 214 834 |

74.3 25.7 100 |

|

Lost job during the COVID-19 No Yes Total |

673 162 835 |

80.6 19.4 100 |

|

Living arrangement Live alone Share a place with friend(s) Live with family Other (Dorm, Shelter, Others) Total |

130 190 419 96 835 |

15.6 22.8 50.2 11.5 100 |

|

Current Marijuana Use No Yes Total |

634 154 788 |

80.5 19.5 100 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (N=835).

- Descriptive and bivariate results

Using bivariate analysis, the sociodemographic variables of age, race, working hours per week, and living with children were significantly associated with current marijuana use (Table 2).

|

Sociodemographic Variables |

Marijuana Use (%) |

No Marijuana Use (%) |

Total (%) |

Chi-Square |

p |

|

Age 18-25 26-30 31-35 36-40 41 or older Total |

80(21.4) 41(23.4) 19(20.9) 6(10.5) 8(9.0) 154 (19.6) |

294(78.6) 134(76.6) 72(79.1) 57(89.5) 89(91.0) 632(80.4) |

374(100) 175(100) 91(100) 57(100) 89(100) 786(100) |

11.82 |

0.02 |

|

Gender Male Female Other Total |

32(22.9) 120(18.7) 2(28.6) 154(19.5) |

108(77.1) 521(81.3) 5(71.4) 634(80.5) |

140(100) 641(100) 7(100) 788(100) |

1.62 |

0.52 |

|

Race/Ethnicity White Black/African Americans Hispanic/Latino Asian Other Total |

118(23.0) 12(16.7) 14(17.7) 5(5.6) 5(18.5) 154(19.5) |

396(77.0) 60(83.3) 65(82.3) 84(94.4) 29(81.5) 634(80.5) |

514(100) 72(100) 79(100) 89(100) 34(100) 788(100) |

17.05 |

0.01 |

|

GPA 2.0-2.49 2.5-2.99 3.0-3.49 3.5-3.99 4.0 or over Total |

1(25.0) 9(34.6) 24(20.3) 77(19.5) 41(17.2) 152(19.4) |

3(75.0) 17(65.4) 94(79.7) 318(80.5) 198(82.8) 630(80.6) |

4(100) 26(100) 118(100) 395(100) 239(100) 782(100) |

4.76 |

0.31 |

|

Marital Status Single/Never married Married Cohabitation Divorced Separated Widowed Other Total |

96(19.8) 36(17.6) 15(34.1) 4(11.8) 0 1(33.3) 2(16.7) 154(19.6) |

389(80.2) 169(82.4) 29(65.9) 30(88.2) 4(100) 2(66.7) 10(83.3) 633(80.4) |

485(100) 205(100) 44(100) 34(100) 4(100) 3(100) 12(100) 787(100) |

9.15 |

0.17 |

|

Working hours per week No job 10 hours or less 11-20 hours 21-30 hours 31-40 hours More than 41 hours Total |

35(16.8) 16(19.5) 42(24.9) 17(23.6) 34(21.5) 10(10.1) 154(19.5) |

173(83.2) 66(80.5) 127(75.1) 55(76.4) 124(78.5) 89(89.9) 634(80.5) |

208(100) 82(100) 169(100) 72(100) 158(100) 99(100) 788(100) |

10.77 |

0.05 |

|

Living with Children No Yes Total |

125(21.3) 29(14.5) 154(19.6) |

462(78.7) 171(85.5) 633(80.4) |

587(100) 200(100) 787(100) |

4.38 |

0.04 |

|

Lost job during the COVID-19 No Yes Total |

117(18.3) 37(24.7) 154(19.5) |

521(82.2) 113(75.3) 634(80.5) |

638(100) 150(100) 788(100) |

3.09 |

0.08 |

|

Living arrangement Live alone Share a place with friend(s) Live with family Other (Dorm, Shelter, Others) Total |

32(26.0) 32(18.0) 69(17.4) 21(25.9) 154(19.5) |

91(74.0) 146(82.0) 328(82.6) 69(74.1) 634(80.5) |

123(100) 178(100) 397(100) 91(100) (100) |

9.01 |

0.11 |

Table 2: Association of sociodemographic variables with marijuana uses among college students (N=835) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note: p values in bold signify significant statistical association.

Another bivariate analysis revealed the psychological variables of anxiety, depression, COVID protective behavior, self-harming thoughts, as well as current smoking and alcohol drinking behavior were significantly associated with current marijuana use (Table 3).

|

Psychological Variables |

Marijuana Use Mean (SD) |

No Marijuana Use Mean (SD) |

Total Mean (SD) |

t-value |

p-value |

|

Anxiety |

9.87(5.38) |

8.53(5.22) |

8.84(5.32) |

2.214 |

0.027 |

|

Depression |

10.95(6.82) |

8.31(5.70) |

8.89(6.06) |

3.801 |

<0.001 |

|

Stress |

36.40(7.47) |

34.69(8.03) |

35.06(8.01) |

1.859 |

0.064 |

|

Loneliness |

19.19(4.95) |

18.07(5.46) |

18.28(3.37) |

1.791 |

0.074 |

|

CPB |

16.46(2.83) |

17.21(3.01) |

17.06(2.99) |

-2.778 |

0.006 |

|

|

Marijuana Use Frequency (%) |

No Marijuana Use Frequency (%) |

Total Frequency (%) |

Chi-Square |

p-value |

|

Self-harming thoughts No Yes Total |

99(17.0) 52(26.9) 151(19.4) |

485(83.0) 141(73.1) 626(80.6) |

584(100) 193(100) 777(100) |

9.25 |

0.002 |

|

Current smoking No Yes Total |

123(17.5) 28(38.4) 151(19.4) |

581(82.5) 45(61.6) 626(80.6) |

704(100) 73(100) 777(100) |

18.43 |

<0.001 |

|

Current alcohol drinking No Yes Total |

18(7.5) 133(24.7) 151(19.4) |

221(92.5) 405(75.3) 626(80.6) |

239(100) 538(100) 777(100) |

31.23 |

<0.001 |

|

EVP No Yes Total |

106(15.3) 47(54.0) 153(19.7) |

585(84.7) 40(46.0) 625(80.3) |

691(100) 87(100) 778(100) |

73.19 |

<0.001 |

Table 3: Association of psychological variables with marijuana uses among college students (N=835) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note: p values in bold signify significant statistical association. CPB: COVID-19 protective behavior. EVP: Electronic vapor products.

- Decision tree results

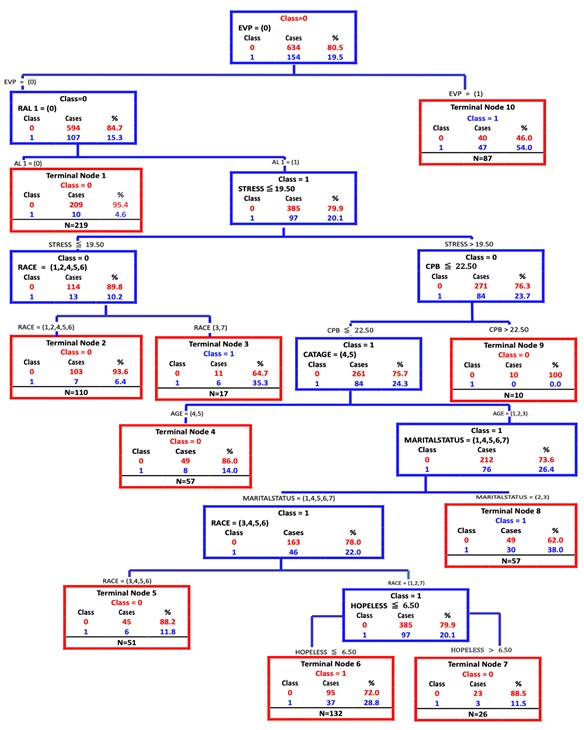

The Classification and Regression Tree (CART) model for recognizing significantly associated factors with marijuana use among U.S. college students during the COVID-19 pandemic is shown in figure 1. The CART algorithm builds a tree model by splitting the independent variable space into regions with similar response variables. The final regions are specified by the terminal nodes of the tree. Each node of the tree specifies conditions that split an existing region. The top-most rectangle in figure 1 is referred to as the root node, which represents 100% of the respondents who answered 1 = yes or 0 = no of which 19.5% (n = 154) of U.S. college students reported using marijuana and 80.5% (n = 634) reported they did not used marijuana during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Classification and regression tree model of marijuana use.

Figure 1: Classification and regression tree model of marijuana use.

Note: EVP: Electronic Vapor Product Use; CPB: COVID-19 Protective Behavior; AL: Alcohol use.

The first split of all the respondents was based on the use of an EVP. Those who used an EVP (n = 87) branched rightward and downward to a terminal node (no further splitting/classification possible), where 47% (n=47) of 87 respondents who used EVP, expressed they used marijuana. Those who did not use an EVP (n=701) branched leftward and downward to a child node (further splitting/ classification possible) where 15.3% of 701 participants reported marijuana use. These results indicate an interaction between college students who are using an EVP and experiencing job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, job loss is significantly associated with marijuana use for college students who are using an EVP.

The second split shows that college students who “did not have at least one drink of alcohol in past 30 days” (n=219) are branched leftward and downward to a terminal node where 10% (n=10) of 219 expressed they had used marijuana. Those who reported drinking alcohol (n=482) branched leftward and downward to a child node, where 20.1% (n=97) of 482 expressed they had used marijuana. These results indicate an interaction between college students who are drinking alcohol without using an EVP and experiencing job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, job loss was significantly associated with marijuana use for college students who are drinking alcohol.

The next nodes are divided by the psychological variable stress. Those who scored less than 19.50 on the stress scale (n=127) among the participants who reported drinking alcohol branched leftward, where 10.2% (n=13) of 127 expressed they used marijuana use. This node continued downward to a final node divided by race. Hispanic or Latino students were more likely to use marijuana than any other racial group. Those who scored higher than 19.50 on stress (n=355) among the participants who are currently drinking alcohol without using an EVP branched rightward, where 23.7% (n=84) of 355 expressed they used marijuana use. These results indicate that participants who had higher stress related to COVID-19 were more likely to use marijuana than those who had less stress related to COVID-19.

The next nodes are divided by COVID-19 protective behaviors. Figure 1 shows that those who scored lower than 22.50 on the CPB scale among the participants who reported lower less level of stress and not using an EVP but drinking alcohol branched leftward where 24.3% (n=84) of 345 expressed they used marijuana use, while those who scored higher than 22.5 on the CPB scale branched rightward, where 0% (n=1) of 10 expressed they used marijuana use. These results indicate that participants who have higher rates of CPB were less likely to use marijuana than those who have lower rates of CPB. The remaining nodes of the regression tree show that age, marital status, and feelings of hopelessness are significantly associated with marijuana use among participants who scored less than 22.5 on the CPB scale and higher than 19.50 on the stress scale among participants who reported alcohol use but not EVP use.

For each class, the highest prediction accuracy was achieved in marijuana use (65.6%), followed by no marijuana use (60.1%). For variable selection, CART software provides “variable importance scores.” The variable that receives a score of 100 indicates the most influential independent variable for predicting marijuana use, followed by other variables, based on their relative importance to the most important one. Based on the variable importance scores, EVP was the most influential variable (100%), followed by current alcohol use (73.9%), stress (32.7%), race/ethnicity (25.2%), loneliness (17.0%), COVID-19 protective behaviors (11.6%), depression (9.6%), age (8.6%), marital status (5.6%), and feelings of hopelessness (4.8%). Anxiety, self-harming thoughts, GPA, current smoking, and gender were not important in the analysis with percentages close to 0.

Discussions

This study utilized classification analysis to identify ordered relations that accurately predict college students' marijuana use following the onset of the pandemic. Our findings confirmed our research hypotheses, indicating that substance use, psychological factors, COVID-19 protective behaviors, and sociodemographic characteristics were significant predictors.

EVP use as a risk factor: EVP use emerged as the most influential predictor of marijuana use among college students. Those who reported using EVPs, such as e-cigarettes and vapes, had a significantly higher prevalence of marijuana use (54.1%) compared to non-users (15.3%). This finding aligns with existing literature [25,26], suggesting that EVPs may serve as a gateway for marijuana use due to their ability to aerosolize and deliver substances like marijuana. Considering this relationship, interventions targeting substances that share the same route of administration as marijuana, such as EVPs, may be particularly effective in reducing marijuana use among college students.

Tobacco use and its impact: Contrary to prior beliefs, our study found that tobacco use had minimal impact on marijuana use among college students, contradicting the notion of tobacco serving as a gateway drug to marijuana [27]. Instead, our findings are consistent with recent evidence indicating that marijuana use often leads to tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence in young adulthood [28,29]. This observation suggests a potential role for marijuana as a reverse gateway to tobacco use, especially given the recent changes in marijuana legalization at the state level [30,31].

Alcohol Use and Co-Use with EVPs: The study revealed that alcohol use was the second strongest correlate of marijuana use among college students. The risk of marijuana use was notably higher when alcohol and EVP use intersected. Specifically, among non-EVP users, those who consumed alcohol had a significantly higher rate of marijuana use (20.1%) compared to those who abstained from alcohol (4.6%). This finding underscores the literature on the progression from alcohol use to marijuana use and later engagement in other drugs, such as cocaine and heroin [27]. It also aligns with the high prevalence of co-use of alcohol and marijuana among young adults [1,6,32]. While such co-use may result in overlapping effects sought by users, it has been associated with negative consequences, including academic performance decline and risky behaviors such as driving under the influence [18,19]. As such, interventions targeting both alcohol moderation and abstinence, along with addressing polydrug use, may be necessary to prevent marijuana use among college students and mitigate potential adverse effects.

Stress as a Risk Factor: Stress emerged as the third strongest correlate of marijuana use among college students. Participants who reported high-stress levels and alcohol use had a significantly higher rate of marijuana use (23.7%) compared to those with low-stress levels (10.2%). This finding aligns with existing literature on motivations for marijuana use among young adults, as psychological problems are often cited as primary reasons for recreational and medical marijuana use [33]. Furthermore, the changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic may have added layers of stress, leading some college students to use substances like marijuana for psychological survival and self-medication [34,35], potentially exacerbating psychological problems such as depression, insomnia, and substance use disorders [36-38]. These findings underscore the importance of considering and addressing life stressors faced by college students, especially in the context of the pandemic, when designing marijuana prevention and treatment initiatives.

Interaction of Stress, Race/Ethnicity, and COVID-19 Protective Behaviors: Stress interacted with race/ethnicity and COVID-19 protective behaviors in predicting marijuana use among college students. Latinx college students who reported low-stress levels and alcohol use were significantly more likely to have used marijuana (35.3%) compared to their White, Black, Asian, Native American, and Native Hawaiian counterparts (6.4%). This finding contrasts with previous studies suggesting similar or lower rates of marijuana use among Latinx students compared to White students [39,40]. The exceptionally high rate of marijuana use among Latinx college students is concerning, given the challenges faced by this fast-growing minority group in accessing substance use treatment [41] and their potential involvement in drug-related offenses within the criminal justice system [42,43]. It calls for marijuana interventions tailored to the unique social and cultural environment and potential impacts of the pandemic among Latinx college students.

While the exact reasons for the higher marijuana use among Latinx college students in this study are not directly measured or explored, we can provide some potential explanations based on existing literature and contextual factors: 1) Cultural and Social Norms: Cultural norms within specific Latinx communities may be more permissive or accepting of marijuana use, leading to higher rates of use among college students belonging to these communities. Additionally, social influences and peer networks can play a significant role in shaping behavior. If marijuana use is prevalent within the students' social circles, it may increase the likelihood of use [44,45]; 2) Acculturative Stress: Latinx college students often face acculturative stress, which stems from adapting to a new culture while retaining cultural heritage elements. This stress may impact coping mechanisms, and some students may turn to marijuana to deal with the challenges of acculturation [46,47]; 3) Environmental Factors: The accessibility and availability of marijuana within specific Latinx communities may be higher, making it easier for college students to access the substance [48]; 4) Economic Disparities: Economic disparities and financial stress experienced by some Latinx college students may contribute to coping behaviors like marijuana use [49,50]; 5) Stress and Coping: As the study shows, stress significantly predicts marijuana use. Latinx college students who reported low-stress levels and used alcohol may still use marijuana as a coping mechanism for other stressors [51,52]; and 6) COVID-19 Pandemic Impact: The COVID-19 pandemic may have disproportionately affected Latinx communities, leading to heightened stress and challenges that may have influenced their marijuana use [53,54].

It is important to emphasize that these are speculative explanations, and the specific reasons for the higher marijuana use among Latinx college students in this study would require further research and in-depth exploration. Addressing these potential factors is essential for developing culturally sensitive and effective marijuana interventions tailored to the unique needs and experiences of Latinx college students. Furthermore, understanding the complexities of substance use patterns in diverse communities, including Latinx college students, requires a comprehensive approach that considers cultural, social, economic, and environmental factors and the impact of historical and systemic inequities. Future research can shed light on the interplay of these factors and contribute to developing targeted and equitable interventions to address substance use issues in college settings.

Finally, stress interacted with COVID-19 protective behaviors, age, and marital status, revealing a unique risk profile. College students who reported high-stress levels adopted relatively fewer COVID-19 protective behaviors, were under 35, married, or cohabiting had a dramatically higher rate of marijuana use (38.0%). This finding highlights the potential positive impact of COVID-19 protective behaviors and is consistent with previous evidence indicating age and spousal substance use as significant indicators of marijuana use [55,56]. Understanding the short-term and long-lasting impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and related behavioral changes on college students' marijuana use is a critical area for future research.

Study Limitations: It is essential to interpret the findings within the context of the study's limitations. The data were collected through surveys, which may be subject to recall and self-report biases. The cross-sectional nature of the data also limits the establishment of causal inferences, as the temporal relationship between variables remains unclear. Caution is needed when generalizing findings to other college student populations, as nonprobability sampling was used to select study participants.

Another notable limitation of our study is the absence of differentiation between states with varying marijuana policies. While the legalization of recreational marijuana has been a significant and evolving trend across the United States, our dataset does not provide information on the specific state-level variations in marijuana legalization status [57]. The differences in marijuana policies among states can substantially impact marijuana use patterns and related behaviors among college students. States with legalized recreational marijuana may experience different rates of use, attitudes toward marijuana, and access to the substance compared to states where marijuana remains illegal [58]. Additionally, the availability of marijuana products and the influence of advertising and marketing strategies might differ between states with contrasting policies [59]. Understanding the effects of state-level marijuana policies on college students' marijuana use is a crucial area for investigation [60]. Research has suggested that the presence of legalized marijuana can influence perceptions of risk and the overall prevalence of use [61]. Additionally, marijuana use laws and regulations can impact college substance use prevention and intervention efforts and influence campus culture and social norms [62]. Unfortunately, due to our dataset's limitations, we could not incorporate state-level differentiation into our analysis. Consequently, the findings of this study provide a broader perspective on marijuana use among college students without delving into the nuances influenced by specific state policies. Future research endeavors should examine the interplay between state-level marijuana policies and college student marijuana use more closely. Utilizing data sources incorporating information on state-specific marijuana legalization status could offer valuable insights into the relationships between policy environments and substance use behaviors [63]. Such investigations would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the contextual factors influencing marijuana use among college students and inform the development of tailored interventions that address state-level variations.

The absence of direct assessment and exploration of acculturative stress and discrimination among Latino college student respondents should be considered as a study limitation. While our study identified a finding of low-stress Latino respondents with higher rates of marijuana use, we acknowledge that acculturative stress and experiences of discrimination may offer significant explanatory insights for this relationship. It is plausible that some low-stress Latino respondents in our sample may have encountered elevated levels of acculturative stress or faced discrimination, which could influence their marijuana use as a coping strategy or means of navigating stressors related to their cultural adaptation and social environment [38]. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize the diverse environments in which Latino College students reside, with some individuals living in crime-filled neighborhoods while experiencing varying stress levels [64]. The intricate interplay between stress, coping mechanisms, and substance use patterns warrants deeper investigation and understanding. As we did not directly assess acculturative stress or discrimination in our study, we cannot fully account for their potential impact on the observed findings. Therefore, our discussion of stress and its association with marijuana use among Latino respondents remains limited without considering these influential factors. Future research endeavors should incorporate specific measures to assess acculturative stress, discrimination experiences, and neighborhood characteristics among Latino college students [65]. By addressing these factors in future studies, we can better understand the complex relationship between stress, cultural experiences, and substance use behaviors within this diverse population.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study identified ordered relationships between variables that accurately predict the probability of marijuana use among U. S. college students after the COVID-19 pandemic. Identifying EVP use, alcohol use and stress level as the three most influential factors for marijuana use contributes to developing effective prevention and treatment programs for college students. The intersections between stress and race and ethnicity, COVID-19 protective behaviors, age, and marital status also generated unique risk profiles. Specifically, college students under a high level of stress who adopted fewer COVID-19 protective behaviors, were relatively young and married or cohabiting reported a high rate of marijuana use. Latinx students with a low stress level who reported alcohol use were also at heightened risk of marijuana use. In this study, a very low rate of marijuana use was observed among those under a high stress level who adopted more COVID-19 protective behaviors. This study revealed the complicated etiology of marijuana use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. It provides specific directions for practice and future research and generates insights on tailored interventions targeting subgroups of college students at high risk for marijuana use.

References

- Jackson KM, Sokolovsky AW, Gunn RL, White HR (2020) Consequences of alcohol and marijuana use among college students: Prevalence rates and attributions to substance-specific versus simultaneous use. Psychol Addict Behav 34: 370-381.

- Wedel AV (2021) Solitary alcohol and cannabis use among college students during the Covid-19 epidemic: Concurrent social and affective correlates and substance-related consequences. Master’s thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, USA.

- Graupensperger S, Jaffe AE, Fleming CNB, Kilmer JR, Lee CM, et al. (2021) Changes in college student alcohol use during the Covid-19 pandemic: Are perceived drinking norms still relevant. Emerg Adulthood 9: 531-540.

- Lechner WV, Laurene KR, Patel S, Anderson M, Grega C, et al. (2020) Changes in alcohol use as a function of psychological distress and social support following COVID-19 related university closings. Addict Behav 110: 106527.

- Casey JL, Cservenka A (2020) Effects of frequent marijuana use on risky decision-making in young adult college students. Addict Behav Rep 11: 100253–100253.

- Gunn RL, Sokolovsky A, Stevens AK, Hayes K, Fitzpatrick S, et al. (2021) Contextual influences on simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in a predominately White sample of college students. Psychol Addict Behav 35: 691-697.

- De'ath G, Fabricius KE (2000) Classification and regression trees: A powerful yet simple technique for ecological data analysis. Ecology 81: 3178-3192.

- Chu DC (2012) The links between religiosity, childhood sexual abuse, and subsequent marijuana use: An empirical inquiry of a sample of female college students. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 56: 937-954.

- McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. (2005) Selection and socialization effects of fraternities and sororities on US college student substance use: A multi-cohort national longitudinal study. Addiction 100: 512-524.

- White HR, Kilmer JR, Fossos-Wong N, Hayes K, Sokolovsky AW, et al. (2019) Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among college students: Patterns, correlates, norms, and consequences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43: 1545-1555.

- Pro G, Sahker E, Marzell M (2018) Microaggressions and marijuana use among college students. J Ethn Subst Abuse 17: 375-387.

- Buckner JD, Heimberg RG, Schmidt NB (2011) Social anxiety and marijuana-related problems: The role of social avoidance. Addict Behav 36: 129-132.

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A (2007) Marijuana use motives: Concurrent relations to frequency of past 30-day use and anxiety sensitivity among young adult marijuana smokers. Addict Behav 32: 49-62.

- Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Le Foll B, George TP, McKenzie K, et al. (2014) The association between cannabis use and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med 44: 797-810.

- Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB (2007) Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana-using young adults. Addictive Behaviors 32: 2238-2252.

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Woods BA (2007) Marijuana motives: Young adults' reasons for using marijuana. Addict Behav 32: 1384-1394.

- Ham LS, Hope DA (2003) College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 23: 719-759.

- Meda SA, Gueorguieva RV, Pittman B, Rosen RR, Aslanzadeh F, et al. (2017) Longitudinal influence of alcohol and marijuana use on academic performance in college students. PLoS One 12: 0172213.

- Cadigan JM, Dworkin ER, Ramirez JJ, Lee CM (2019) Patterns of alcohol use and marijuana use among students at 2- and 4-year institutions. J Am Coll Health 67: 383-390.

- Firkey MK, Sheinfil AZ, Woolf-King SE (2020) Substance use, sexual behavior, and general well-being of U.S. college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A brief report. J Am Coll Health 70: 2270-2275.

- Sokolovsky AW, Hertel AW, Micalizzi L, White HR, Hayes KL, et al. (2021) Preliminary impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on smoking and vaping in college students. Addict Behav 115: 106783.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166: 1092-1097.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams J (2001) The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16: 606-6013.

- Feldt RC (2008) Development of a brief measure of college stress: The College Student Stress Scale. Psychol Rep 102: 855-860.

- Kim YK (2021) Gender-moderated associations between adolescent mental health, conventional substance use, and vaping. Children and Youth Services Review 129: 106193.

- Trivers KF, Gentzke AS, Phillips E, Tynan M, Marynak KL, et al. (2019) Substances used in electronic vapor products among adults in the United States, 2017. Addict Behav Rep 10: 100222.

- Tullis LM, Dupont R, Frost-Pineda K, Gold MS (2003) Marijuana and tobacco: A major connection. J Addict Dis 22: 51-62.

- Badiani A, Boden JM, De Pirro S, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, et al. (2015) Tobacco smoking and cannabis use in a longitudinal birth cohort: Evidence of reciprocal causal relationships. Drug Alcohol Depend 150: 69-76.

- Cohn A, Villanti A, Richardson A, Rath JM, Williams V, et al. (2015) The association between alcohol, marijuana use, and new and emerging tobacco products in a young adult population. Addict Behav 48: 79-88.

- Marijuana Moment (2022) Bipartisan lawmakers file amendments to federal marijuana legalization bill up for house ote this week. Marijuana Moment.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy (2014) National drug control strategy: Data supplement. Office of National Drug Control Policy, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Lee CM, Cadigan JM, Patrick ME (2017) Differences in reporting of perceived acute effects of alcohol use, marijuana use, and simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 180: 391-394.

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, Small JW, Schlauch RC, et al. (2008) Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. Journal of Psychiatric Research 42: 230-239.

- Zhao Q, Cepeda A, Chou CP, Valdez A (2021) Incarceration Trajectories and Mental Health Problems Among Mothers Imprisoned in State and Federal Correctional Facilities: A nationwide study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 1-19.

- Zysset A, Volken T, Dratva J (2021) Preventive and risky health behavior of Swiss university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Public Health 31: 164-015.

- Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Swift W, Carlin JB, et al. (2013) The persistence of the association between adolescent cannabis use and common mental disorders into young adulthood. Addiction 108: 124-133.

- Wittchen HU, Fröhlich C, Behrendt S, Günther A, Rehm J, et al. (2007) Cannabis use and cannabis use disorders and their relationship to mental disorders: A 10-year prospective-longitudinal community study in adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 88: S60-S70.

- Zvolensky MJ, Bonn-Miller MO, Bernstein A, Marshall EC (2019) Marijuana use motives: A confirmatory test and evaluation among young adult marijuana users. Addictive Behaviors 94: 10-16.

- Lac A, Unger JB, Basáñez T, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, et al. (2011) Marijuana use among Latino adolescents: Gender differences in protective familial factors. Substance Use & Misuse 46: 644-655.

- McCoy SI, Jewell NP, Hubbard A, Gerdts CE, Doherty IA, et al. (2010) A trajectory analysis of alcohol and marijuana use among Latino adolescents in San Francisco, California. Journal of Adolescent Health 47: 564-574.

- Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, Keefe K (2011) Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 50: 22-31.

- Hodgdon H (2008) Juvenile offenders and substance use and abuse. The Future of Children, Juvenile Justice.

- Roblyer ZMI, Grzywacz JG, Cervantes RC, Merten MJ (2016) Stress and alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among Latino adolescents in families with undocumented immigrants. Journal of Child and Family Studies 25: 475-487.

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML (2014) Ethnic labels and ethnic identity as predictors of drug use among middle school students in the Southwest. Journal of Research on Adolescence 24: 143-158.

- Valdez LA, Brown LM, Chavez J, Padilla B (2019) Stressful Life Events and Urban African American Adolescents' Perceived Positive School Climate: The Role of Culturally Relevant Social Support. Journal of Black Psychology 45: 235-257.

- Smokowski PR, Evans CBR, Cotter KL, Webber KC (2018) Ethnic Identity and Acculturative Stress as Mediators of Depression Among Hispanic Adolescents. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16: 160-176.

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J (2020) Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist 75: 1051-1063.

- Rigg KK, Monnat SM (2015) Urban vs. rural differences in prescription opioid misuse among adults in the United States: Informing region specific drug policies and interventions. International Journal of Drug Policy 26: 484-491.

- Shim R (2018) Racial and Ethnic Minority College Students' Stigma Associated With Seeking Psychological Help: Examining Psychocultural Correlates. Journal of College Student Development 59: 311-326.

- Acosta J, Posselt JR, Perez P, Hernandez JR (2021) The Role of Financial Stress in College Persistence among Latinx Students. The Review of Higher Education 44: 647-676.

- Pacheco JS, Benjet C, Medina-Mora ME, Pérez-Cuevas R (2017) Childhood adversity and neighborhood stressors during the transition from childhood to adolescence: Predictors of young adult depression. Child Abuse & Neglect 70: 131-142.

- Feldman S, Weinberger AH, Platt J, Goodwin RD (2020) Perceived stress as a risk factor for changes in health behavior and sleep during COVID-19. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 54: 229-237.

- Cantor J, Lebrón AMW, Adia AC, Mendez RS, Cook BL (2021) Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationally representative study of US adults. Preventive Medicine 148: 106583.

- Fortuna LR, Tolou-Shams M, Robles-Ramamurthy B, Porche MV, Inkelas M (2022) Child and Family Health Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 51: 223-241.

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR (2007) Predictors of marijuana use among married couples: The influence of one's spouse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 91: 121-128.

- Terry-McElrath YM, Patrick ME (2018) Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among young adult drinkers: Age-specific changes in prevalence from 1977 to 2016. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 42: 2224-2233.

- Johnson JK (2020) Marijuana policy: What research tells us. Annual Review of Public Health 41: 163-182.

- Pacula RL, Powell D (2017) Analyzing the relationship between marijuana use and marijuana policies. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 36: 420-457.

- Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS (2017) Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 170: 1-8.

- Dilley JA, Hitchcock L, McGroder N, Greto LA, Richardson SM (2013) The impact of the medical marijuana law on marijuana-related arrests in Washington State. Journal of Drug Policy Analysis 6: 1-16.

- Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Stohl M, et al. (2017) US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws: 1991-1992 to 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry 74: 579-588.

- Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Biglan A (2017) Medical Marijuana Legalization and Marijuana Use Among Youth in Oregon. The journal of primary prevention 38: 329-341.

- Pacula RL, Smart R, Kilmer B (2018) State medical marijuana laws, marijuana use and perceived availability of marijuana among the general US population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 185: 341-346.

- Flores A, Gaither SE, Deardorff J (2021) Stress and health behaviors among young adult Latinx college students: The role of acculturation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 50: 911-925.

- Perreira KM, Ornelas IJ, Perreira KM (2016) The physical and psychological health of immigrant children. In: Bornstein MH (ed.). The handbook of parenting 4: 327-357.

Citation: Moon SS, Zhao Q, Pooler D, Kim YY, Maleku A, et al. (2024) Marijuana Use among College Students after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Classification and Regression Tree Approach. J Addict Addictv Disord 11: 172.

Copyright: © 2024 Sung Seek Moon, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.