Nephroblastoma: the Protocols should be Changed

*Corresponding Author(s):

António Gentil MartinsDepartment Of Pediatric And Adolescents Oncology, Portuguese Cancer Institute Of Francisco Gentil, Lisbon, Portugal

Tel:+351 939555162,

Email:agentilmartins@gmail.com

Abstract

This paper, based on a personal experience of more than 200 Nephroblastoma in the World’s 1st multidisciplinary Pediatric Cancer Unit-1960, where 53 partial nephrectomies were performed (23 bilateral and 30 unilateral cases), compares the likeliness of Partial Nephrectomy in Unilateral Nephroblastoma (around 20% instead of the 3% found in the literature, when using the classical International pre-operative chemotherapy Protocols and the more intensive preoperative chemotherapy proposed), adding an Anthracycline (Doxorubicin or Epirubicin) to the classical Actinomycin D and Vincristine, so demonstrating that the Protocols on pre-operative chemotherapy should be changed.

Also it advises that the invasion of a contiguous organ (like spleen, colon or liver) is not a contraindication for Partial Nephrectomy, provided one can perform mono-block surgery. Finally advises that complete para-aortic-cava lymphadenectomy should be routinely performed.

Keywords

Nephroblastoma; Partial Nephrectomy; Pre-operative chemotherapy; Prevention; Radicality

INTRODUCTION

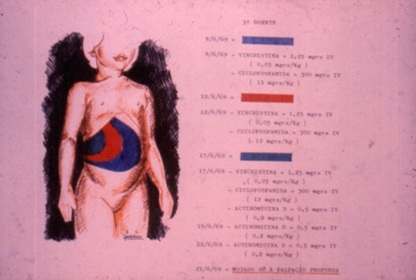

It was at the first SIOP Meeting in Madrid, in 1969 that for the first time I presented the Pre-Operative Poly-Chemotherapy (VAC) for Nephroblastoma, drastically reducing the size of the tumor, at a time that the French school was proposing pre-operative Radiotherapy [1]. It took around 5 years for it to become the therapy of choice in comparison with the classical Roentgen Therapy proposed by the French School [2]. Then, pre-operative chemotherapy became the rule in the SIOP Protocol (Figure 1).

Figure 1: (A Gentil Martins - Wilms tumor) Marked reduction in size with pre-operative chemotherapy (1st SIOP Madrid 1969).

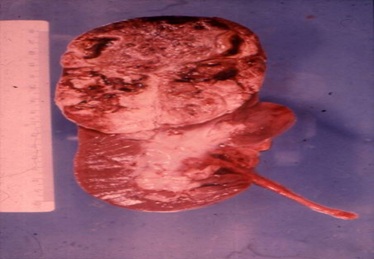

In 1982, in Berne, at the 14th SIOP Meeting, I presented for the first time,12 successful Partial Nephrectomies for Unilateral Nephroblastoma (following pre-operative 3 drugs Chemotherapy ) But it took more than 20 years for the possibility of performing partial Nephrectomy in Unilateral Nephroblastoma to became acceptable internationally [3,4] (Figure 2). We hope that these new ways (more intensive pre-operative chemotherapy, partial Nephrectomy (provided that mono-block excision is possible!) and para-aortico-cava lymphadenectomy), my take less time to be accepted [5,6] .

Figure 2: The good results obtained led us to think about being conservative and perform partial nephrectomies in unilateral cases.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We believe to be a clear advantage theuse a different form of pre-operative chemotherapy than the one advised by the SIOP Protocol [2,7,8]. We include the use of an anthracycline (Epirubicin), additionally to the use of the classics Actinomycin D and Vincristine, thus increasingmarkedly the chances for a more conservative surgery (partial and not total nephrectomy), with the preservation of more nephrons. Our Radical/Conservative approach (maximal effect with the least injury to the Patient in the future, thus improving his life perspectives) means that we assure total safe removal of the tumor but at the same time preserve the maximal possible normal kidney parenchyma. We compare the percentage of partial nephrectomies performed inn unilateral tumors according to our pre-operative chemotherapy Protocol with the one according to the SIOP’s Protocol.

SIOP Protocol (2016) Pre-operative chemotherapy: Actinomycin D 45yg/Kg; Vincristine 1,5mg/m2; Post-operative Doxorubicin: no more than 300mg/m2.

Suggested Protocol: Actinomycin D 45y/m2 IV; Vincristine 1.2mg/m2 IV, weekly, for 4 weeks prior to operation, plus at operation and for further 4 weeks after surgery.

Epirubicin 20mg/m2 IV once a week, for 4 weeks prior to operation (total 80mg/sqm) (or Doxorubicin, as SIOP) (taking into account that that dosage is far below the maximal recommended one, referred above, which should never exceed 300mgs/m2).

Surgical technique

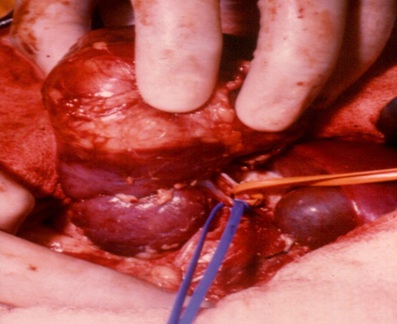

After a transverse supra-umbilical laparotomy, examinations of the contralateral kidney if pre-operative imaging is not completely clear. Placement of moist swabs around the kidney (so isolating the operative filed, as a precaution for an eventual rupture). Placement of a sling around the renal pedicle, not tied, as a precaution for an eventually uncontrollable bleeding during surgery (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Vascular pedicle controlled.

Figure 3: Vascular pedicle controlled.

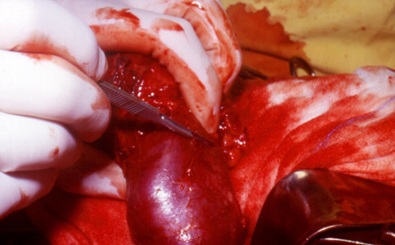

Then, only the vessels for the tumor are ligated. In order to maintain as much as possible the renal blood flow to the normal kidney segment, we tend to maintain digital compression of the main vascular pedicle to the kidney (with intermittent occlusion), during the circular incision of the kidney capsule, always performed in good health kidney tissue (away from the tumor margin and not forgetting that the tumor tends to go deeper in the renal parenchyma) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Incision in healthy kidney away from the tumor.

Figure 4: Incision in healthy kidney away from the tumor.

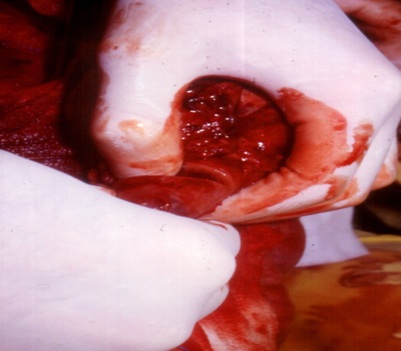

Then follows deepening the incision (eventually with the help of blunt digital dissection), obliquely inwards, until the conic incision is completed and the tumor removed (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Deepening the incision, with the help of the finger

Figure 5: Deepening the incision, with the help of the finger

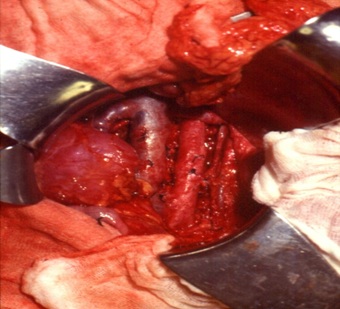

Then follows ligations of any vessels bleeding in the raw kidney surface, suturing of the calyces and renal pelvis and joining together the kidney capsule, so closing the kidney wall.

If there are any doubts about being radical with the excision (when looking at the operative specimen) a further slice of the kidney is removed (or even total Nephrectomy is performed). Eucleation is completely unacceptable, except when there has been a previous Nephrectomy in the opposite side (the tumor is central or very extensive), and in cases of multiples lesions, as in Nephroblastomatoses.

Then we perform the removal of the tissues of the kidney bed (peri-renal fat, etc.) and also perform a radical para-aortic-cava lymphadenectomy (till the level of the homo-lateral iliac vessels), considering that, according to international literature, around 5% of patients, before the use of chemotherapy, have presented lymph glands metastases [9] (Figures 6 and 7). The remaining of the kidney is repositioned, with nephropexy, followed by closure of the laparotomy in layers and leaving a drain in the renal bed, through a separate stab incision (to be kept usually for 2 days).

Figure 6: Excision completed and healthy kidney tissue preserved.

Figure 6: Excision completed and healthy kidney tissue preserved.

Figure 7: Preserved kidney and tumor bed including lymphadenectomy.

DISCUSSION AND RESULTS

The diagnoses was always based on clinical and radiological data (namely CT and MRI Scans) and open biopsy or even FNAC were never used or recommended (although we use generally this last approach in the majority of others types of children’s tumors) [10,11]. After surgery, the different histological sub types of Nephroblastoma can be determined (namely Low risk, Intermediate risk and High risk tumors), as well as definitive staging, so that further chemotherapy can be adapted accordingly.

We also have to take into account the problems that may arise with concomitant urological and nephrological disorders as well as genetic syndromes, eventually more relevant than the risk of hyperperfusion nephropathy [12]. In SIOP 2001, it was referred that tumor volume seemed to be a significant risk factor and should be a risk stratification factor for a sub-group of Nephroblastoma.

We believe that, even without histology as yet available ( not excluding the risk of a wrong diagnoses without histology, as standard radiology and existing discriminating biomarkers assessment are not always conclusive), pre-operative Poly-Chemotherapy is a must, as it can markedly improve the chances of a good result [2]. Reducing the tumor size may make surgery easier and allow for a quicker and easier access to the renal pedicle (ligating almost simultaneously the 2 vessels, but always starting with the artery). By reducing the tumor volume chemotherapy allows for lesser complications, namely ruptures, the vascular invasion (thrombus in the cava) may partially regress and, above all, partial Nephrectomy (conservative but still radical) becomes possible in around 20% of the Patients instead of the 3% found in the literature [13]. It is obvious that the size of the tumor is not the only factor to take into account in order to opt for a partial nephrectomy and more relevant is certainly its technical safety, allowing for excision in normal kidney tissue and at least preservation of a good blood supply.

The main reason for poly-chemotherapy is because one can attack at different phases of the cell cycle: Actinomycin D attacks at G1 and G2, Vincristine at M and finally Epirubicin at S ( an Anthracycline that we believe should also be routinely used pre-operatively but that the SIOP Protocol, unfortunately, does not consider.

We do not minimize that Anthracyclines, even liposomal, can induce oxidative stress and apoptosis, eventually leading to late cardiac deficiency, as there is no minimal those considered safe. Thus, ECG control is advisable before the 3rd injection particularly taking into account the ejection fraction of the left ventricle, in order to allow for the early detection of an eventual acute cardiac failure [14]. But we also know that 300 mgs/sqm of an Anthracycline is considered to be me maximal does to be used in order to avoid cardio-toxicity sequelae [14,15]. The dose we suggest is only 80mgs/m2 and it is obvious that, if further anthracycline is required post operatively, the maximal dose advisable would be only 220mgs/m2 and not the generally accepted 300mgs/m2.

One of the more important reasons for the preservation of kidney tissue (even in this era of renal transplantation), is the fact that, in around 5% to 10% of the cases (in our Institution 5 out of 57 in the last 10 years and in our personal experience, before that, even more than 10%), the tumor is bilateral (either initially or some time later) [16]. Also we must not exclude eventual trauma, congenital malformations, syndromic lesions, hyperperfusion nephropathy, infections, etc., as a further reason to try to preserve kidney parenchyma, all patients requiring a careful and complete global evaluation [12,15].

Operative time is only slightly increased, something that is not really relevant. And above all, our aim is not only to cure the patients but to give them the best possible quality of life (avoiding hemodialysis or kidney transplantation), looking always to preserve the maximum kidney tissue compatible with radical surgery (certainly not limited by the 66% of remaining normal parenchyma advised by SIOP 2016 ) [17-38].

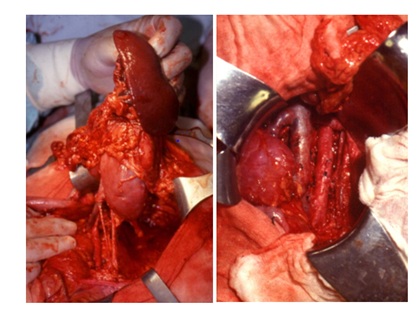

We also completely disagree with the SIOP statement (point 5, of Surgery guidelines) that, when another organ is invaded, partial nephrectomy should not be attempted. For us, the contraindication will only to be limited by the impossibility of a mono-block excision. We had good examples of this, namely a patient with a tumor of the upper pole of the left kidney invading the spleen, in which we performed a mono-block partial nephrectomy/splenectomy, and another with a tumor of the upper pole of the right kidney that invaded the liver, the problem being solved through mono-block partial Nephrectomy/marginal liver resection.

Figure 8: Left: initial appearance Mono-block Partial Nephrectomy /Splenectomy.Right: final result in another patient.

Figure 8: Left: initial appearance Mono-block Partial Nephrectomy /Splenectomy.Right: final result in another patient.

During partial nephrectomy we initially tended to maintain occlusion of the main renal pedicle during all tumor removal: that might have been the reason why we had 3 patients in which the preserved part of the kidney ceased to function. Although that is not statistically significant, we believe that intermittently decompressing the main renal pedicle can avoid that problem (which might have been the result of a too long period of vascular occlusion). We contraindicate the pre-operative use of radiotherapy and also consider it totally unacceptable after partial Nephrectomy, (even with the low dose proposed by SIOP = 10 to 12 Grays), as it would jeopardize the gain in kidney function obtained through nephron sparing surgery.

There have been no problems related to performing a complete para-aortico-cava lymphadenectomy, which we believe should be a routine procedure (probably the reason why we never had the local recurrences described by some, who just perform lymph glands sampling) and it is obvious that, if other localized glands (namely in pelvis), are seen, they must certainly also be excised.

In a group of 23 “bilateral” patients, 20 were alive at least 5 years after treatment was completed. 2 died of lung metastases and 2 of kidney failure (kidney transplantation not possible due to lack of donors) (a 5 years survival of 83%) [35].

In our recent Institution figures, we had 5 stage 5 tumors in 57 patients, what is somewhat similar to SIOP (7%). And it is important to state that, in the above figures, cases of Congenital Mesoblastic Nephromas, Clear Cell tumors or Malignant Rabdoidtumors, are not included.

In a group of 30 “unilateral” patients, in whom I have performed partial nephrectomy, 28 are alive and well (at least five years after ending treatment), (although 4 have lost renal function in the preserved renal parenchyma (which we attribute to a too long time clamping of the renal pedicle and that now has been substituted by intermittent compression by the Assistant (as referred above), 2 died of lung metastases and one was lost to follow-up. But none has shown local recurrence. A 5 years survival of at least 90% or 93.5% if including the one lost to follow-up.

Using the SIOP’s recommended pre-operative chemotherapy, and according to SIOP’s literature, partial nephrectomies in unilateral cases were limited to only 3%. In our Institution (IPOFG Lisboa), in the last 10 years, our successors using the SIOP Protocol, found Stage I = 44, Stage II = 1 Stage III = 2 Stage IV = 7 Stage V = 5 patients: But from the 44 Stage I cases, partial nephrectomy were performed only once, when using the SIOP Protocol: In both cases, an obviouslymuch lower figure than ours 20%, with more intensive pre-operative chemotherapy.

CONCLUSION

We believe present Internacional Guidelines should definitely be revised, by adding an Anthracycline to the classical Actinomycin D and Vincristin, in the pre-operative period, because through further reducing pre-operatively the size of the tumor, it becomes more likely the possibility that partial nephrectomy can be performed, with its obvious advantages of the preservation of normal nephrons, that might be of great value in the future (namely in bilateral cases). Comparing our chemotherapy protocol with the figures of the followers quoted in the SIOP documents, gives us a difference of around 20% against just 3%, what we believe to be extremely important and certainly very significant. Those are not simply “personal feelings, but concrete facts”, that it is essential to take into account. Also it is fundamental to consider that the invasion of an adjacent organ iscertainly not a contraindication for partial nephrectomy provided a “one block excision” can be performed. Finally, a para-aortic-cava lymphadenectomy should also be a routine procedure in the surgery of Nephroblastoma.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The paper is a single author piece and presents no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- Martins AG (1969) The treatment of Wilms Rumor. Symposium de Oncologia Pediatrica Madrid.

- Thomas PR (1997) Wilms’ Tumor: Changing Tole of Radiation Therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol 7: 204-211.

- Martins AG (1992) Staging designation for bilateral Wilms' tumors. Med Pediatr Oncol 20: 87.

- Martins AG, Souzinha M, España M (2005) Justificar-se-há a Nefrectomia parcial nos Nefroblastomas Unilaterais ? X Congresso Nacional de Oncologia.

- Willital GH, Kiely E, Gohary AM, Gupta DK, Minju Li M, et al. (2005) Partial Nephrectomy for Nephroblastomas Gentil Martins A. Atlas of Children’s Surgery PABST 405-406.

- Martins AG (1982) Operative Chemotherapy for Unilateral Nephroblastomas. Proceedings of the 14th SIOP Meeting – Berne.

- Ziegler M, Azizkhan R, Weber T (2003) Operative Pediatric Surgery McGRAW-HILL, USA. Davidoff A M Shochat S J (2003) Oncology 99 Nephroblastoma (Wilms Tumor) McGRAW-HILL, USA.

- Farber S (1966) Chemotherapy in the treatment of leukemia and Wilms' tumor. JAMA 198: 826-836.

- Oberholzer HF, Falkson G, de Jager CL (1992) Successful management of inferior vena cava and right atrial nephroblastoma tumor thrombus with preoperative chemotherapy. Medical and Pediatric Oncology 20: 61-63.

- E Haagedoorn (1994) Essential Oncology for Health Professionals. Van Gorcum, Netherlands, 171-178.

- Mattei P (2003) Surgical Directives Pediatric Surgery Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 427-635.

- Ritchey ML, Green DM, Thomas PR, Smith GR, Haase G et al. (1996) Renal failure in Wilms’ tumor Patients : a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group. Medical and Pediatric Oncology 26:75-80.

- Green DM, Breslow NE, Beckwith GB (1998) Comparison between single dose and divided dose administration of dactinomycin and doxorubicin for Patients with Wilms tumor: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol 16: 237-245.

- Vejpongsa P, Yeh ET (2014) Prevention of Anthracyclin induced Cardiotoxicity Challenges and opportunities. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 938-945.

- Henriksen PA (2018) Anthracycline cardiotoxicity :an update on mechanisms, monitoring and prevention. Heart 104: 971-977.

- Alves RC (2016) Senior Consultant IPOFG (Instituto Português de Oncologia Francisco Gentil) / Hospital D. Estefânia (Children’s Hospital) Lisboa – personalcommunication.

- Coppes MJ, Arnold M, Beckwith JB (1999) Factors affecting the risk of contralateral Wilms Tumor development: a report from the National Wilms´TumorStudy Group. Cancer 85: 1616-1625.

- Horwitz JR, Ritchey ML, Moksness J, Breslow NE, Smith GR, et al. (1996) Renal salvage procedures in patines with synchronous bilateral Wilms tumors : A report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group. J Pediatr Surg 1996;31:1020-1025.

- Horowitz M, Shah SM, Ferzli G, Syad PI, Glassberg KI (2001) Laparoscopic partial upper pole nephrectomy in infants and children. BJU Int 87: 514-516.

- Yao D, Poppas DP (2000) A clinical series of laparoscopic nephrectomy, nephroureterectomy and heminephroureterectomy in the pediatric population. Journal of Urology 163: 1531-1535.

- McNeil DE, Langer JC, Choyke P, DeBaun MR (2002) Feasibility of partial nephrectomy for Wilms tumor in children with Beckwith-Wiedeman n syndrome who have been screened with abdominal ultrasonography. J Pediatr Surg 37: 57-60.

- Ritchey ML (1996) Primary Nephrectomy for Wilms tumor : approach of the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. Urology 47: 787-791.

- Othersen HB Jr, DeLorimer A, Hrabovsky E, Kelalis P, Breslow N et al. (1990) Surgical evaluation of lymph node metastases in Wilms tumor´. J Pediatr Surg 25: 330-331.

- Benson CD, Mustard WT, Ravitch MM, Snyder Jr WH, Welch KJ (1962) Pediatric Surgery. Chapter 52 Retroperitoneal tumors Renal Tumors. Medical Publishers Inc., Page no: 860- 874.

- Holder TM, Ashcraft KW (1980) Pediatric Surgery Chapter 70. Wilms´Tumor, Jphnson DG (ed.). WB Saunders Company, Pennsylvania, USA, Pg no: 932-943.

- Mitus A, Tefft M, Fellers FX (1969) Long term follow-up of renal function s of 108 children who underwent nephrectomy for malignant disease. Pediatrics 44: 912-921.

- Sullivan MP (1968) Vincristine ( NCS-67574) therapy for Wilms´ Tumor. Cancer Chemother Rep 52: 481-484.

- Wolff JA, D'Angio G, Hartmann J, Krivit W, Newton WA Jr (1974) Long term evaluation of single versus multiple courses of Actinomycin D Therapy of Wilms tumors´. N Engl J Med 290: 84-86.

- Mason Brown JJ (1963) Surgery of Childhood Edward Arnold (Publishers), London. (Higgins TT, Williams DTI The Genito-Urinary System Neoplasms of the kidney 1221-1226). Zachariou Z (2009) Pediatric Surgery Digest (ed). Springer, Spain.

- Nixon HH (1978) Surgical conditions in paediatrics. Butterworth-Heinemann Limited, UK; Pg No: 448.

- Dennison WM (1974) Surgery in Infancy and Childhood Churchill Livingstone (3rd Ed 16 Genito-Urinary System Pg no. 325-326, and 25 Cancer and Radiotherapy in Childhood Pg no 579-583.

- Blakely ML, Ritchey ML (2001) Controversies in the management of Wilms Tumor. Semin Pediatr Surg 10: 127-131.

- Tröbs RB, Hänsel M, Friedrich T, Bennek J (2001) A 23 year experience with malignant renal tumors in infancy and childhood. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 11: 92-98.

- Umbrella Protocol SIOP RTSG 2016 Version 1.2 October 2016 Endra CT number 2016-0004180-39.

- Willital GH, Keily E, Gohary A, Gupta DK, Li M, et al. (2006) Atlas of Children’s Surgery. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg Pg no: 1.

- van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Hol JA, Pritchard-Jones K, van Tinteren H, Furtwängler R, et al. (2017) A Rationale for the treatment of Wilms tumor in the UMBRELLA SIOP-RTSG 2016 protocol. Nature Reviews Urology 14: 743-752.

- Wang J, Tang MLD, Gu W, Mao J, Shu Q (2019) Current treatment for Wilms tumour: COG and SIOP standards World Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2: 38.

- Chintagumpala M, Muscal JA (2019) Treatment and prognoses of Wilms Tumor. UpToDate, Massachusetts, USA.

Citation: Martins AG (2020) Nephroblastoma: the Protocols should be Changed. J Hematol Blood Transfus Disord 7: 025.

Copyright: © 2020 António Gentil Martins, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.