Occurrence of Malaria and Intestinal Helminths among Students from Selected Secondary Schools in Port Harcourt Area of Rivers State, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author(s):

Uzor CADepartment Of Science Laboratory Technology, School Of Science And Technology, Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnic, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Tel:+2348030728972,

Email:uzorchinedui@yahoo.com

Abstract

Occurrence of malaria and Intestinal helminths among students from three senior secondary schools in Port Harcourt, rivers state, Nigeria was conducted from March to July 2017. Blood and stool samples were each collected from two hundred and forty three (243) students. Questionnaires and oral communication were used to obtain information and observable epidemiological factors. Standard parasitological procedusres were employed in sample collection and examination. Blood samples were examined for the presence of malaria parasite using microscopy and Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) kits, and the stool samples were examined for intestinal helminths using formol-ether concentration technique. Data obtained were analysed using SPSS. Results indicated 109 (44.86 %) prevalence of malaria parasite, 4 (1.65%) intestinal parasitic helminths and 1 (0.43%) co-infection respectively. Two intestinal parasites of Hookworm 3 (1.23%) and Taenia spp. 1(0.41%) were identified. Plasmodium and hookworm were the only co-infection detected. However, highest prevalence of malaria 11 (57.89%) and intestinal helminths 2 (1.32%) was observed among the age range of 12-13 and 14-15 years. The study indicated a relatively high prevalence of malaria parasite, a low prevalence of intestinal helminths and a low level of co-infection but a need for malaria intervention programmes among the study areas.

Keywords

Co-infection; Hookworm; Intestinal helminths; Malaria; Plasmodium; Taenia spp

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is an acute fever related illness caused by the transmission of the parasite to people by the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. If untreated within 24 hours, P. falciparum malaria can progress to severe illness, often leading to death. Among the parasites that cause malaria, the most deadly is Plasmodium falciparum and it is the most prevalent in Africa, where cases of malaria and deaths are heavily concentrated [1]. In 2015, roughly 3.2 billion people, almost half of the world’s population were at risk of malaria [2]. As published by the latest WHO estimates in December 2016, there were 212 million cases of malaria in 2015 (of this figure, the WHO African region accounts for 90% of the global malaria cases, with the South-East Asia region and Eastern Mediterranean region accounting for 7% and 2% respectively) with 429 000 deaths [3]. In individuals with compromised or lowered immune systems, symptoms manifest in about 7 days or more (usually 10-15 days) after the infective mosquito bite. The initial symptoms which may include headache, fever, chills and vomiting – may be mild and difficult to recognize as malaria.

An intestinal parasite is an organism that infects the human (and other animals) gastrointestinal tracts [4]. They may be found in other parts of the body, but they have an affinity for the walls of the intestines. These parasites may gain access into the body through the ingestion of undercooked meat, intake of untreated or infected water and penetration via the skin. These intestinal parasites cause morbidity and mortality if not properly handled. Intestinal parasitic infection has worldwide endemicity and it poses a significant medical health concern in developing countries where they present a high rate of prevalence [5, 6]. About 3.5 billion people are estimated to be affected, with 450 million showing signs of illness resulting from these infections, the majority being children. These nematodes are associated with significant degrees of morbidity and mortality in children. Anaemia, poor growth, reduced physical activity, impaired learning ability, malnutrition, dysentery, fever, dehydration and vomiting are amongst the numerous symptoms associated with helminthiasis in children [7]. Protein energy malnutrition, intra uterine weight gain and low pregnancy weight are also related to helminthic infection [5]. Gastrointestinal nematodes such as Hookworm, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuristrichiura, Enterobius vermicular is and S. stercoralis are very common in children between the ages of 0 and 12years world over [8,9].

One of the transmission routes may be through contaminated soil, improperly washed or faecally contaminated fingers or sometimes penetration through the skin and migration to the intestine [10]. Some factors that are intimately linked with the transmission of intestinal parasites are poor sanitation, poverty, poor education, inadequate healthcare, inadequate personal hygiene and lack of clean water [11]. Other factors such as polluted environments, heaps of refuse, clogged gutters and overflowing sewage units around living places and overcrowded neighbourhoods equally increase the likelihood of intestinal parasitic agents to cause infection [12]. The study examines the occurrence of malaria and intestinal helminths among students from three Senior Secondary Schools in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

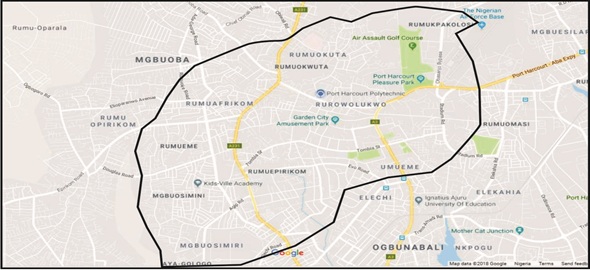

The city Port Harcourt encompasses two Local Government Areas in Rivers State; Port Harcourt and Obio-Akpor Local Government Areas. Obio-Akpor is in the metropolis of Port Harcourt, and it is a major hub of economic activities in Nigeria, and one of the major cities of the Niger Delta, located in Rivers State. Obio-Akpor covers 260 km2 and at the 2006 Census held a population of 464,789 [13]. It is a cosmopolitan city harbouring people of different works of life including those that are low, medium and high income earners. This research work was conducted at the selected secondary schools located in Obio-Akpor (Rumuola, Rumueme and Mgbuoshimini) which are spread in different parts of the city (Figure 1) with students from different backgrounds.

Figure 1: Map of study area.

Figure 1: Map of study area.

Sample collection

Three senior secondary schools were selected for the collection of stool and blood samples from the students. A letter of consent (from parents/guardians) with an attached questionnaire was given to SS1 and SS2 students with a sample bottle to go home with. Where consent is given, the sample bottles (with stool) were returned with the answered questionnaire and a date fixed for the collection of blood samples. The questionnaire was designed to gather demographic data. Students whose parents/guardians failed to give consent returned the empty sample bottles (and letters).A total of 900 sample bottles were distributed to the students of the three schools. Two hundred and forty three sample bottles were returned with stool while the rest were either returned empty or not at all. Dates were chosen at the convenience of the schools for the collection of blood samples from those who returned the sample bottles with stool.

Blood samples were collected by venepuncture method from the 243 students whose stool samples had been collected. Rapid Diagnostic Tests using Care StartTM Malaria HRP2 (Pf) kits were carried out at the point of blood collection according to the manufacturer’s instruction and the results recorded. The blood samples were then stored in EDTA bottles which were labelled with an identification number (code) and sent to Laboratory of the Department of Animal and Environmental Biology for storage and further microscopic examination.

Thick and thin blood films were made using the method of Ishaleku and Mamman [14].The stained slides were then examined with immersion oil under the light microscope using x100 objective lens and the results recorded accordingly [15]. Faecal samples were examined using the formol-ether Concentration technique (sedimentation method) [15]. A cover slip placed on the sediment and was viewed under the microscope. The results were also recorded.

Data analysis

Demographic data obtained from administered questionnaires and results obtained from the parasitological examinations were analysed using simple percentages and chi-square tests. This was done using the SPSS version 20.

Ethical clearance and informed consent

The permission to carry out this work was sought and obtained from the Office of Research Ethics Committee, University of Port Harcourt. Permission to collect samples from the selected schools was obtained from the Rivers State Senior Secondary School Board and the Authorities of the selected schools. A letter of consent was issued to the students to give to their parents/guardians, giving the children a right to reject or accept to participate in the study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A total of 243 blood and stool samples each were obtained from randomly selected students of the three schools in Obio Akpor Local Government Area in Rivers State. Of the 243 blood and stool sampled, malaria infection had a prevalence of 109 (44.86%) and the intestinal helminths had 4 (1.65%) as shown in table 1. Niger Delta Science School, Rumuola (NDSS), had the highest prevalence (83.33%) for malaria infection for the students sampled as compared to Comprehensive Secondary School, Mgboshimini (CSSM) with a prevalence of 53.19% and 38.76% for Model Girls Secondary School, Rumueme (MGSS). This result is significant (with χ2 = 14.7645 and p-value of 0.0006 at p <0.05). Niger Delta Science School, Rumuola (NDSS), also had the highest prevalence (5.56%) for intestinal helminth infection for the students sampled as compared to Comprehensive Secondary School, Mgboshimini (CSSM) with a prevalence of 4.26% and Model Girls Secondary School, Rumueme (MGSS) which had 0.56%. This result is significant (with χ2 = 27.3609 and p-value of < 0.00001 at p < 0.05).

|

School |

No. examined |

Malaria Infected (%) |

Intestinal Helminths Infected (%) |

|

MGSS |

178 |

69 (38.76) |

1 (0.56) |

|

CSSM |

47 |

25 (53.19) |

2 (4.26) |

|

NDSS |

18 |

15 (83.33) |

1 (5.56) |

|

TOTAL |

243 |

109 (44.86) |

4 (1.65) |

|

χ2 |

|

14.7645 |

27.3609 |

|

P |

|

0.0006 |

< 0.00001 |

Table 1: Overall occurrence of malaria parasite and intestinal helminths among the studied population.

Prevalence of malaria parasite among students from the studied schools based on sex

The prevalence of malaria based on sex showed that of the 10 males sampled, microscopic examination revealed that 6 (60%) were positive for the infection while 103 (44.2%) of the total females examined were positive as shown on table 2. This sex related prevalence was not significantly different (χ2 = 0.967 with p-value is 0.3254) as seen in table 2. Based on the results from RDT tests carried out, 4 (40%) of the males were positive, but the females showed positive results for 51 (21.89%) of those tested. Though there was a high difference in the percentage occurrence of the males (40%) against the females (21.89%), there was no significant difference statistically at χ2 = 1.7962 with p-value is 0. 1802 (at p < 0.05) as shown in table 2.

|

Sex |

No. examined |

Microscopy Prevalence (%) |

RDT Prevalence (%) |

|

M |

10 |

6 (60) |

4 (40) |

|

F |

233 |

103 (44.21) |

51 (21.89) |

|

Total |

243 |

109 (44.86) |

55 (22.63) |

|

χ2 |

|

0.967 |

1.7962 |

|

P |

|

0.3254 |

0.1802 |

Table 2: Comparison of prevalence of Malaria by Sex from RDT and Microscopy examinations.

Prevalence of malaria parasite among students from the studied schools based on age

The occurrence of malaria parasite among the students from the different schools based on age showed that the age range of 12-13 had the highest occurrence for both microscopy (57.89%) and RDT (31.58%) table 3. It also showed that there was a generally higher positive result from the microscopy than the RDT results obtained, but this did not show any significance with a χ2 = 1.1069 with a P-value of 0.775421(at p< 0.05) for microscopy and χ2 = 1.0985 with a P-value of 1.77744 (at p< 0.05) for RDT.

|

AGE (years) |

No. examined |

Microscopy |

RDT |

|

Infected (%) |

Infected (%) |

||

|

12 -13 |

19 |

11 (57.89) |

6 (31.58) |

|

14-15 |

152 |

66 (43.42) |

32 (21.05) |

|

16-17 |

64 |

30 (46.88) |

16 (25) |

|

18-20 |

8 |

2 (25) |

1 (12.5) |

|

χ2 |

|

1.1069 |

1.0985 |

|

P |

|

0.775421 |

0.77744 |

Table 3: Comparison of prevalence of Malaria by Age from Microscopy and RDT examinations.

Distribution and predominant intestinal helminths among different schools studied

The frequencies of species of helminth eggs seen among the studied population showed that hookworm had the highest infection rate with 1.23% as against Taenia spp. with 0.41%. The prevalence of helminth eggs among the schools as shown on table 4 reveals that CSSM had the highest number of helminth infection with one case each for hookworm (2.13%) and Taenia spp. (2.13%). NDSS had a case of hookworm with 5.56% showing the highest prevalence and MGSS had the least prevalence of 0.56% with a case of Hookworm.

|

Source of Data |

Type of Helminth |

||

|

|

Hookworm |

Taenia spp. |

|

|

No. examined |

No. infected (% Prevalence) |

No. infected (% Prevalence) |

|

|

MGSS |

178 |

1 (0.56) |

Nil (0) |

|

CSSM |

47 |

1 (2.13) |

1 (2.13) |

|

NDSS |

18 |

1 (5.56) |

Nil (0) |

|

Total |

243 |

3(1.23) |

1(0.41) |

Table 4: Distribution and predominant intestinal helminths.

Occurrence of species of intestinal Helminths among the different schools studied by sex

Table 5 shows that females had the highest prevalence 4 (1.72%) of infection compared to their male counterparts where there was no infection recorded.

|

SEX |

No examined |

Infected (%) |

Not infected (%) |

|

M |

10 |

0 (0) |

10 (100) |

|

F |

233 |

4 (1.72) |

229 (98.28) |

|

χ2 |

|

|

0.1885 |

|

P |

|

|

0.34 |

Table 5: Occurrence of Intestinal helminths by Sex.

Occurrence of species of intestinal helminths among the different studied schools by age

Occurrence of intestinal helminths among the population studied based on age (Table 6) showed that of different age ranges, no infection was recorded among students between the ages of 12-13. The prevalence of infection in the age range of 14-15 recorded 2 (1.32%) positive results out of the 152 students examined. Out of 64 within the age bracket of 16-17, 2 (3.13%) infections were recorded. There was no positive result for students between the ages of 18-20.

|

AGE (years) |

No examined |

Infected (%) |

|

12-13 |

19 |

0 (0) |

|

14-15 |

152 |

2 (1.32) |

|

16-17 |

64 |

2 (3.13) |

|

18-20 |

8 |

0 (0) |

|

Total |

243 |

4 (1.65) |

Table 6: Occurrence of Intestinal Helminths by Age.

Co-infection of malaria and intestinal parasites among the students

Only a case of co-infection of malaria parasite and hookworm was identified from the 243 students examined. This occurrence was observed in a female NDSS student who was positive for malaria parasite and hookworm egg. This showed a prevalence of 1 (0.43%) out of the 233 female students examined as shown in table 7. On a general note, this prevalence accounts for 0.41% of the entire population examined. There was no observed co-infection of malaria parasite and Taenia spp.

|

School |

Sex |

No. examined |

MP + Hookworm No. infected (%) |

MP + Taenia spp. No. infected (%) |

|

Total |

M |

10 |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

|

F |

233 |

1 (0.43) |

0 (0) |

Table 7: Co-infection with Malaria and Intestinal parasites among the studied population.

This study showed an overall prevalence (44.86%) of malaria infection and this agrees with the report by Atting et al. [16] who carried out a study on intestinal and malaria parasitic infections among school age children in a rural community in AkwaIbom State, Nigeria where a prevalence of 42.6% was recorded for malaria. The result is also closeto the malaria prevalence of 52.3% obtained by Ajayi et al. [16] on the prevalence of malaria among children living in selected rural communities in Ibadan Nigeria. The prevalence value obtained in this study is lower than the value of 63.3% obtained by Abah and Temple [17] where 300 students were examined in Angiama community in Bayelsa State and the result was higher than the 12.8% prevalence rate recorded by Bin Mohanna et al. [18] who conducted a survey on malaria signs and infection among a total of 469 school children.

However, the difference observed could be due to seasonal changes and environmental factors which predispose them to infection. The prevalence of helminths in this study was low (1.65%) compared to a prevalence of 11.9 % recorded by Njunda et al. [19]. This result was equally very low when compared to results obtained by Gimba and Dawam [20] who recorded a prevalence of 28.0% from the samples examined and a prevalence of 71.2% recorded by Amali et al. [21] who examined 250 samples from Nyiev-Tiev, a rural community in Niger State, Nigeria.The very low level of prevalence recorded in this study could be as a result of improved personal hygiene practices employed by the study participants and their age (12-20 years) that may be very conscious of food and water they consume and the surroundings in which they work and play. The co-infection rate recorded from this study was 0.43% representing only one (1) individual from the entire study population. This result is close to that obtained by Ishaleku and Mamman [14] where overall malaria parasite and helminth co-infection was 4.7% but much lower than results obtained by Solomon et al. [22] where a high prevalence was recorded and in this case all participants with intestinal parasites were positive for malaria.

Similar low prevalence of 4.3% was reported by Ojurongbe et al. [23] from a previous study in Osun state, Nigeria. Bolaji et al. [24] reported a prevalence of 20.1% of polyparasitism in the area studied and this result does not agree with the result of this study. Ajayi et al. [16] reported a co-infection prevalence of 48.2% as observed in their study and Abanyie et al. [25] reported a co-infection prevalence of 55% which are higher than results observed in this study. This result could be as a result of lifestyle and improved environmental sanitation conditions. The intestinal helminths observed in this study were hookworm and Taenia spp. and the most prevalent was hookworm with 1.23% compared to 0.41% recorded for Taenia spp.The prevalence of hookworm in this study was close to a prevalence of 2.3% obtained by Ugbogu and Asogu [26] and 5.5% obtained by Oyeniran et al. [27], but did not agree with the results from Atting et al. [16] with a prevalence of 10.3%, Abah and Arene [28] who observed a prevalence of 25% and Amali et al. [21], who recorded a prevalence of 47.6% from the study population. Based on the prevalence of Taenia spp. (0.41%) recorded from this study, it was observed to be close to results obtained by Thomas et al. [29] with a prevalence of 3.0%, Biu and Hena [30] with a prevalence of 4.2% and Biu et al. [31] with a prevalence of 4.3%. Results on the prevalence of Taenia spp. was lower than the 8.40% prevalence recorded by Eke et al. [32] and a far cry from the 40.9% recorded by Mogaji et al., [33]. The low prevalence of Taenia spp. recorded in this study could be as a result of low consumption of pork in the diets of the tested students and the absence of pigs in the neighbourhoods where they reside.

Results obtained from present study showed the number of students infected with malaria and intestinal helminths and prevalence of malaria parasite among the studied schools to be 109 (44.86%) and intestinal helminths to be 4 (1.65%). This shows that there is a need for effective control measure to further reduce the incidence of malaria infection among the study population. The reduced prevalence of intestinal parasites could be as a result of better hygiene practices by the students in our public schools and possible improved sanitary conditions of their environment. The age of the participants would have also played a role in the reduced prevalence owing to awareness on the need for improved hygiene practices.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

There was a relatively high prevalence of malaria parasite and a low prevalence of intestinal helminths.Highest prevalence of malaria 11 (57.89%) and intestinal helminths 2 (1.32%) was observed among the age ranges of 12-13 and 14-15 years.

The following are recommended:

- Government should intensify distribution of Long Lasting Insecticide Treated Nets (LLIN) to inhabitants of Obio Akpor Local Government Area.

- Water reservoirs that serve as breeding sites for mosquitoes should be properly managed.

- Mass deworming activities should be carried out to ensure that intestinal helminths are ultimately eradicated in these parts.

- The drinking of water from safe and clean sources and the adoption of water treatment practices should be encouraged to reduce the risk of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors are grateful to the Office of Research Ethics Committee, University of Port Harcourt for ethical permission. Permission to collect samples from the selected schools was obtained from the Rivers State Senior Secondary School Board and the Authorities of the selected schools.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in the paper.

REFERENCES

- WHO (2016) Fact sheet: World malaria report 2016. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- WHO (2016) Soil transmitted helminth infections. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Loukopoulos P, Komnenou A, Papadopoulos E, Psychas V (2007) Lethal Ozolaimus megatyphlon infection in a green iguana (Iguana iguanarhinolopa). J Zoo Wildl Med 38: 131-134.

- Kotian S, Sharma M, Juyal D, Sharma N (2014) Intestinal parasitic infection, prevalence and associated risk factors, a study in the general population from the Uttarakhand hills. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health 4.

- Arora DR, Arora B (2007) Medical Parasitology. CBS Publishers, New Delhi, India.

- Nzeako SO, Nwaimo NC, Kafaru OJ, Onoja H (2013) Nematode parasitemia in school aged children in sapele, Delta State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology 34:129-133.

- Crompton DW (1999) How much human helminthiasis is there in the world? J Parasitol 85: 397-403.

- Eze CN, Nzeako SO (2011) Intestinal helminths amongst the hausa and fulani settlers at obinze, owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. Nigeria Journal of Parasitology 32: 225-229.

- Blaser MJ, Ravindin JI, Guerrant RL (2008) Gastrointestinal tract infections. In: Richard VG, Hazel M. D, Derek W, Mark Z, Peter LC, Ivan MR, et al., MIMS Medical Microbiology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Asaolu SO, Ofoezie IE, Odemuyiwa PA, Sowemimo OA, Ogunniyi TAB (2002) Effect of water supply and sanitation on the prevalence and of ascaris lumbricoides among pre-school age children in ajebandele and Ifewara, Osun State, Nigeria. Transactions of Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 96: 600-604.

- Phiri K, Whitty CJ, Graham SM, Ssembatya-Lule G (2000) Urban/rural distance in prevalence of intestinal helminths in southern Malawi. Ann. Top. Med. Parasite 94: 381-387.

- Wikipedia (2017) Intestinal parasites.

- Cheesbrough M (2006) District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Ishaleku D, Mamman AS (2014) Co-Infection of Malaria and Helminthes Infection among Prison Inmates. Journal of Microbiology Research and Reviews 2: 1-5.

- Atting IA, Ukoh VJ, Usip L, Ebere N (2016) Prevalence of intestinal and malaria parasitic infections among school age children in a rural community (NkwotNko) in AkwaIbom State, Nigeria. American Journal of Research Communication 4.

- Ajayi IO, Afonne C, Dada-Adegbola H, Falade CO (2015) Prevalence of asymptomatic malaria and intestinal helminthiasis co-infection among children living in selected rural communities in Ibadan Nigeria. American Journal of Epidemiology and Infectious Disease 3: 15-20.

- Abah AE, Temple B (2015) Prevalence of malaria parasite among asymptomatic primary school children in angiama community, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Tropical Medicine & Surgery 4: 1.

- Bin Mohanna MA, Bin Ghouth AS, Raja’a YA (2007) Malaria signs and infection rate among asymptomatic school children in Hajr valley, Yemen. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 13: 35.

- Njunda AL, Fon SG, Assob JCN, Nsagha DS, Kwenti TDB, et al. (2015) Coinfection with malaria and intestinal parasites, and its association with anaemia in children in Cameroon. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 4.

- Gimba UN, Dawam NN (2015) Epidemiological status of intestinal parasitic infection rates in children attending Gwagwalada township clinic, FCT-Abuja, Nigeria. American Journal of Research Communication 3: 97-110.

- Amali O, Anyam RW, Jeje PN, Olusi TA (2013) Soil-transmitted nematodes and hygiene practices in a rural community of Benue state, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology 34: 147-152.

- Solomon L, Okere HC, Daminabo V (2014) Understanding human malaria: Further review on the literature, pathogenesis and disease control. Report and Opinion 6: 55-63.

- Ojurongbe O, Adegbayi MA, Bolaji SO (2011) Asymptomatic falciparum malaria and intestinal helminths co-infection among school children in Osogbo, Nigeria. J Res Med Sci 16: 680-686.

- Bolaji OS, Akinleye CA, Agunbiade BT, Akindele AA, Adeleke AD, et al. (2016) Coinfection of malaria and intestinal parasites among school children in Agaba, Southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Microbial & Biochemical Technology 3: 157-164.

- Abanyie AF, McCracken C, Kirwan P (2013) Ascaris co-infection does not alter malaria-induced anaemia in a cohort of Nigerian preschool children. Malar J 12:1.

- Ugbogu OC, Asogu GO (2013) Prevalence of intestinal parasites amongst school children in unwana community, Afikpo, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology 34: 69-71.

- Oyeniran OA, Ojurongbe O, Oladipo EK, Afolabi AY, Ajayi OO, et al. (2014) Intestinal parasitic infection among primary school pupils in Osogbo Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) 13: 96-101.

- Abah AE, Arene FOI (2015) Status of intestinal parasitic infections among primary school children in rivers state, Nigeria. Journal of Parasitology Research 2015: 1-7.

- Thomas HZ, Jatau ED, Inabo HI, Garba DD (2014) Prevalence of intestinal helminths among primary school children in Chikun and Kaduna South Local Government areas of Kaduna state, Nigeria. Journal of Medicine and Medical Research 2: 6-11.

- Biu AA, Hena SA (2008) Prevalence of human Taeniasis in Maiduguri, Nigeria. International Journal of Biomedical and Health Sciences

- Biu AA, Rabo JS, Dawurung JS, Kolo MA (2011) Studies on the prevalence of tapeworm infection in Yobe State indigenes, Nigeria. Stem Cell 2: 3-4.

- Eke SS, Oguniyi T, Omalu ICJ, Otuu CA, Udeogu VO, et al. (2014) Prevalence of human Taeniasis among school children in some selected primary schools in Bosso Local Government Area, Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. International Journal of Applied Biological Research. 6: 80-86.

- Mogaji HO, Adeniran AA, Fagbenro MT, Olabinke DB, Abe EM, et al. (2016) Prevalence of human taeniasis in odeda area of Ogun State, Nigeria. International Journal of Tropical Disease & Health 17: 1-8.

Citation: Uzor CA, Eze NC, Nduka FO (2020) Occurrence of Malaria and Intestinal Helminths among Students from Selected Secondary Schools in Port Harcourt Area of Rivers State, Nigeria. J Environ Sci Curr Res 3: 017.

Copyright: © 2020 Uzor CA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.