Relationship Between Preoperative SIRI, AISI, and MLR Levels and Prognosis in Patients with NSCLC: A Retrospective Cohort Study

*Corresponding Author(s):

Yu MaoDepartment Of Thoracic Surgery, The First Hospital Of Hohhot, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China

Email:hhhtmaoyu_2025@163.com

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to investigate the correlation between preoperative systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), adjusted systemic immune-inflammation index (AISI), and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) with the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), in order to provide new clinical reference for the prognostic evaluation of NSCLC patients.

Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on the clinical medical records of 69 NSCLC patients who received initial treatment at Hohhot First Hospital, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, from January 2020 to May 2025. According to follow-up and clinical laboratory records, patients were divided into the disease progression group and the non-progression group. Baseline data were analyzed, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the predictive value of the relevant indices for the prognosis of NSCLC patients.

Results: SIRI, AISI, MLR, and their combined indicators have significant value in predicting the prognosis of patients with NSCLC. In the prediction using individual indicators, SIRI, AISI, and MLR all demonstrated significant predictive value, with SIRI showing the best predictive performance. In terms of combined prediction using multiple indicators, the combination of AISI and MLR yielded the best predictive effect. According to the optimal cut-off value, a stratified analysis of the enrolled patients revealed that high preoperative levels of SIRI, AISI, and MLR indicated poor prognosis.

Conclusion: AISI, SIRI, and MLR serve as important indicators for the prognostic evaluation of patients with NSCLC. They not only accurately reflect the body's inflammatory and immune status but can also be applied in combination for the prognostic evaluation of patients with NSCLC, providing a novel diagnostic perspective and approach for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords

AISI; MLR; NSCLC; Prognosis; SIRI

Introduction

With the development of globalization and population aging, the incidence rate and mortality rate of cancer have increased sharply. Among them, lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer (accounting for 11.6% of total cases) and the leading cause of cancer-related death (accounting for 18.4% of total cancer deaths) [1]. According to statistics from the Chinese National Cancer Center in 2022, lung cancer has the highest incidence rate (21.98%) and mortality rate (28.49%) in China, and it is also the leading cause of cancer death in both males (31.66%) and females (23%) [2]. Based on different histological type, lung cancer is mainly divided into two major subtypes: small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Small cell lung cancer accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancer cases [3,4], while NSCLC accounts for about 85% of all lung cancer cases, with the main histological subtype being adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma [5]. Among them, adenocarcinoma accounts for approximately 40% of lung cancer cases, squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 25-30% of all lung cancer cases, and large cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 5-10% of lung cancer cases [6-9].

In recent years, studies have indicated that peripheral blood-related inflammatory markers are associated with malignant tumors and have potential value in prognostic diagnosis [10-14]. In the field of lung cancer research, the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), adjusted systemic immune-inflammation index (AISI), and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) play important roles in predicting the response of patients with NSCLC to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and surgical treatment. These markers provide an objective reference for the optimization of clinical treatment strategies and prognostic evaluation by quantifying the balance between the immune and inflammatory states of the body [15-22].

Materials And Methods

Study patients

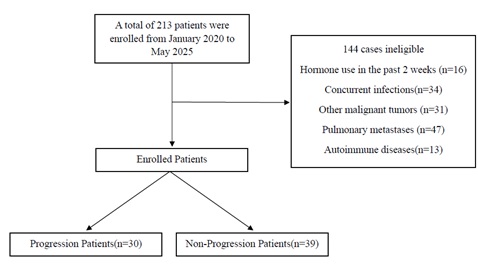

This study included 69 patients with primary NSCLC who received initial treatment at the Hohhot First Hospital, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, from January 2020 to May 2025 (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria: initial treatment; diagnosis of NSCLC confirmed by clinical evaluation, surgical pathology, and imaging; complete hematological test reports within one week before surgery; complete and detailed medical records. Exclusion criteria: patients who received hematopoietic factors or hormone therapy within the past two weeks; those with concurrent acute infections or infections at other sites; patients with other malignant tumors or serious primary diseases; recurrence of lung cancer or metastasis of primary tumors from other sites to the lungs; patients with hematologic system diseases, bone marrow hematopoietic system diseases, autoimmune diseases, or systemic diseases. The clinical data collected in this study included: general information such as sex, age, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, and history of underlying diseases (hypertension, diabetes); blood test reports within one week before surgery. Among them, the SIRI is defined as the ratio of the product of neutrophil count and monocyte count to lymphocyte count; the AISI is defined as the ratio of the product of platelet, neutrophil, and monocyte counts to lymphocyte count; and the MLR is defined as the ratio of monocyte count to lymphocyte count.

Figure 1: Flow diagram.

Figure 1: Flow diagram.

Follow up

Postoperative follow-up is conducted through diversified approaches to ensure comprehensive and timely understanding of the patient's recovery status. Specifically, the follow-up mainly includes two categories: Outpatient Re-examination, which involves face-to-face consultations, relevant imaging examinations (such as CT, ultrasound, etc.), laboratory tests (such as complete blood count, biochemical indicators, etc.), and physical examinations to intuitively assess the recovery of physical functions after surgery; Telephone Follow-up, during which medical staff contact the patient or their family members by phone to inquire in detail about the patient's daily symptoms, medication usage, dietary and sleep patterns, and provide targeted health guidance. The deadline for this follow-up work is May 1, 2025. All patients who meet the follow-up criteria before this date are included in the follow-up system.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 statistical software and GraphPad Prism 9.0. First, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data: for variables with a normal distribution, the t-test was used for intergroup comparisons; for variables with a non-normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. For categorical data, the χ2 or Fisher's exact test was used for comparison. To evaluate the predictive ability of inflammatory markers, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was plotted, and the area under the curve (AUC), cut-off values, specificity (SP), sensitivity (SE), and Youden index were calculated. Based on the cut-off value as the threshold, stratified comparisons were conducted for data at different levels. Multiparameter combined testing was conducted using logistic regression and ROC curve comprehensive analysis. The presentation of measurement data was as follows: data conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s); data not conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as median (lower quartile, upper quartile) [M (Q1, Q3)]. All tests were two-sided and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Basic clinical data of the investigators included in the study

In this study, there were 30 cases in the progression group and 39 cases in the non-progression group. The number of male/female patients was 48:21, with a mean age of 65.101.33 years. The number of smokers/non-smokers was 22:47; the number of patients with/without a history of alcohol consumption was 16:53; the number of patients with/without hypertension was 22:47; and the number of patients with/without diabetes was 9:60. The median neutrophil level was 4.36 (3.185, 5.235) × 109/L, the median lymphocyte level was 1.53 (1.04, 2.015) × 109/L, and the monocyte level was (0.46 ± 0.22) × 109/L. The median platelet level was 226 (187, 281) × 109/L, the median MLR was 0.293 (0.2118, 0.3998), the median SIRI was 1.16 (0.7811, 2.3802), and the median AISI was 277.4636 (139.9349, 542.0455). There were statistically significant differences between the two groups in neutrophil count (P = 0.012), monocyte count (P = 0.001), SIRI (P < 0.05, Table 1).

|

Characteristics |

Non-progression group |

Progression group |

χ2/t/Z value |

P value |

|

Gender |

|

|

0.356 |

0.551 |

|

Male |

26 (54.2) |

22 (45.8) |

|

|

|

Female |

13 (61.9) |

8 (38.1) |

|

|

|

Smoking history |

|

|

0.051 |

0.821 |

|

Ever |

12 (54.5) |

10 (45.5) |

|

|

|

Never |

27 (57.4) |

20 (42.6) |

|

|

|

Alcohol history |

|

|

0.001 |

0.980 |

|

Ever |

9 (56.3) |

7 (43.8) |

|

|

|

Never |

30 (56.6) |

23 (43.4) |

|

|

|

Hypertension |

|

|

1.610 |

0.205 |

|

Ever |

10 (45.5) |

12 (54.5) |

|

|

|

Never |

29 (61.7) |

18 (38.3) |

|

|

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

|

|

0.089 |

0.766 |

|

Ever |

6 (66.7) |

3 (33.3) |

|

|

|

Never |

33 (55) |

27 (45) |

|

|

|

Age(year) |

62.95 ± 1.90 |

67.90 ± 1.73 |

-1.88 |

0.064 |

|

Neutrophil count(109/L) |

3.75 (2.93, 5.06) |

4.86 (4.2925, 5.915) |

-2.5 |

0.012 |

|

Lymphocyte count(109/L) |

1.57 (0.98, 2.04) |

1.47 (1.07, 2.0125) |

-0.617 |

0.537 |

|

Monocyte count(109/L) |

0.4 ± 0.2451 |

0.5473±0.3403 |

-0.14733 |

0.001 |

|

Platelet(109/L) |

217 (187, 271) |

231.5 (204.5, 296.25) |

-1.798 |

0.072 |

|

BMI |

23.1 (21.11, 24.22) |

21.6 (20.37, 24.60) |

-1.077 |

0.281 |

|

SIRI |

0.95 (0.68, 1.28) |

1.80 (1.15, 2.55) |

-3.692 |

<0.001 |

|

AISI |

179.60 (115.97, 323.29) |

490.88 (247.62, 874.01) |

-3.704 |

<0.001 |

|

MLR |

0.24 (0.19, 0.30) |

0.37 (0.27, 0.52) |

-3.553 |

<0.001 |

Table 1: Comparison of general data between the two groups n(%).

The value of preoperative inflammatory markers in predicting the prognosis of patients with NSCLC

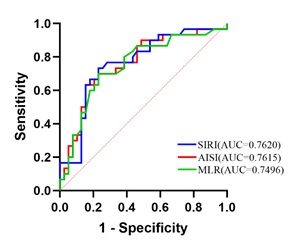

Auxiliary predictive value analysis of individual indicator testing: To evaluate the auxiliary value of SIRI, AISI, and MLR in predicting the prognosis of patients with NSCLC, ROC curve was plotted using the above variables as test variables. The results showed that the AUC of SIRI was 0.762. The cut-off value obtained from the ROC curve for SIRI was 1.2861, with the corresponding maximum Youden index of 0.503, sensitivity (SE) of 0.733, and specificity (SP) of 0.769. Similarly, the AUC of AISI was 0.7615, with a cut-off value of 367.2837, SE of 0.633, and SP of 0.846; the AUC of MLR was 0.7496, with a cut-off value of 0.3055, SE of 0.7, and SP of 0.769 (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Figure 2: ROC curves of peripheral blood individual indicators for predicting prognosis in NSCLC patients.

Figure 2: ROC curves of peripheral blood individual indicators for predicting prognosis in NSCLC patients.

|

Biomarker |

Cut-off value |

SE |

SP |

Youden |

AUC |

|

SIRI |

1.2861 |

0.733 |

0.769 |

0.503 |

0.762 |

|

AISI |

367.2837 |

0.633 |

0.846 |

0.479 |

0.7615 |

|

MLR |

0.3055 |

0.7 |

0.769 |

0.469 |

0.7496 |

Table 2: The Evaluation Role of Individual Indicator Tests in NSCLC

Based on the cut-off values of the test variables SIRI, AISI, and MLR, the enrolled patients were divided into low-index groups and high-index groups. The clinical data of the two groups were analyzed, and the results showed that: Patients in the low SIRI group had a better prognosis than those in the high SIRI group (P < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in gender, smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, or diabetes (all P > 0.05, Table 3); Patients in the low AISI group had a better prognosis than those in the high AISI group (P < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in gender, smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, or diabetes (all P > 0.05, Table 4); Patients in the low MLR group had a better prognosis than those in the high MLR group (P < 0.001). There was a statistically significant difference in gender (P = 0.029), while no statistically significant differences were found in smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, or diabetes (all P > 0.05, Table 5).

|

Group |

number |

Gender |

Smoking history |

Alcohol history |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Ever |

Never |

Ever |

Never |

|||

|

low SIRI group |

38 |

24(50) |

14(66.7) |

13(59.1) |

25(53.2) |

10(62.5) |

28(52.8) |

|

|

high SIRI group |

31 |

24(50) |

7(33.3) |

9(40.9) |

22(46.8) |

6(37.5) |

25(47.2) |

|

|

χ2 |

|

1.64 |

0.211 |

0.464 |

||||

|

P value |

|

0.2 |

0.646 |

0.496 |

||||

|

Group |

number |

Hypertension |

Diabetes Mellitus |

prognosis |

||||

|

Ever |

Never |

Ever |

Never |

non-progression group |

progression group |

|||

|

low SIRI group |

38 |

12(54.5) |

26(55.3) |

4(44.4) |

34(56.7) |

30(76.9) |

8(26.7) |

|

|

high SIRI group |

31 |

10(45.5) |

21(44.7) |

5(55.6) |

26(43.3) |

9(23.1) |

22(73.3) |

|

|

χ2 |

|

0.004 |

0.108 |

17.309 |

||||

|

P value |

|

0.952 |

0.743 |

<0.001 |

||||

Table 3: Comparison of clinical characteristics between patients in the low SIRI group and high SIRI group n(%).

|

Group |

number |

Gender |

Smoking history |

Alcohol history |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Ever |

Never |

Ever |

Never |

||

|

low AISI group |

44 |

29(60.4) |

15(71.4) |

14(63.6) |

30(63.8) |

11(68.8) |

33(62.3) |

|

high AISI group |

28 |

19(39.6) |

6(28.6) |

8(36.4) |

17(36.2) |

5(31.3) |

20(37.7) |

|

χ2 |

|

0.767 |

<0.001 |

0.224 |

|||

|

P value |

|

0.381 |

0.988 |

0.636 |

|||

|

Group |

number |

Hypertension |

Diabetes Mellitus |

prognosis |

|||

|

Ever |

Never |

Ever |

Never |

non-progression group |

progression group |

||

|

low AISI group |

44 |

13(59.1) |

31(66) |

5(55.6) |

39(65) |

33(84.6) |

11(36.7) |

|

high AISI group |

28 |

9(40.9) |

16(34) |

4(44.4) |

21(35) |

6(15.4) |

19(63.3) |

|

χ2 |

|

0.306 |

0.032 |

16.873 |

|||

|

P value |

|

0.58 |

0.859 |

<0.001 |

|||

Table 4: Comparison of clinical characteristics between patients in the low AISI group and high SIRI group n(%).

|

Group |

number |

Gender |

Smoking history |

Alcohol history |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Ever |

Never |

Ever |

Never |

||

|

low MLR group |

39 |

23(47.9) |

16(76.2) |

11(50) |

28(59.6) |

10(62.5) |

29(54.7) |

|

high MLR group |

30 |

25(52.1) |

5(23.8) |

11(50) |

19(40.4) |

6(37.5) |

24(45.3) |

|

χ2 |

|

4.752 |

0.559 |

0.303 |

|||

|

P value |

|

0.029 |

0.455 |

0.582 |

|||

|

Group |

Number |

Hypertension |

Diabetes Mellitus |

prognosis |

|||

|

Ever |

Never |

Ever |

Never |

non-progression group |

progression group |

||

|

low MLR group |

39 |

12(54.5) |

27(57.4) |

4(44.4) |

35(58.3) |

30(76.9) |

9(30) |

|

high MLR group |

30 |

10(45.5) |

20(42.6) |

5(55.6) |

25(41.7) |

9(23.1) |

21(70) |

|

χ2 |

|

0.051 |

0.179 |

15.192 |

|||

|

P value |

|

0.821 |

0.672 |

<0.001 |

|||

Table 5: Comparison of clinical characteristics between patients in the low MLR group and high SIRI group n(%).

Auxiliary predictive value analysis of multiple indicator tests

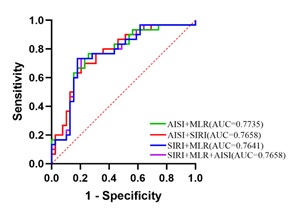

To evaluate the auxiliary value of multiple indicators on the prognosis of patients with NSCLC, random non-repetitive combinations of SIRI, AISI, and MLR were performed. Logistic regression and ROC curve comprehensive analysis were conducted, and the ROC curves for combined multi-indicator detection were plotted (Figure 3). The results showed that the AUC for the combination of AISI and MLR was 0.7735, with a corresponding maximum Youden index of 0.469, SE of 0.7, and SP of 0.769. Similarly, the AUC for the combination of AISI and SIRI was 0.7658, with SE of 0.733 and SP of 0.821; the AUC for the combination of SIRI and MLR was 0.7641, with SE of 0.767 and SP of 0.744; the AUC for the combination of SIRI, MLR, and AISI was 0.7658, with SE of 0.733 and SP of 0.795 (Table 6).

Figure 3: ROC curves of multiple peripheral blood indicators for predicting prognosis in NSCLC patients

Figure 3: ROC curves of multiple peripheral blood indicators for predicting prognosis in NSCLC patients

|

biomarker |

SE |

SP |

Youden |

AUC |

|

AISI+MLR |

0.7 |

0.769 |

0.469 |

0.7735 |

|

AISI+SIRI |

0.733 |

0.821 |

0.554 |

0.7658 |

|

SIRI+MLR |

0.767 |

0.744 |

0.51 |

0.7641 |

|

SIRI+MLR+AISI |

0.733 |

0.795 |

0.528 |

0.7658 |

Table 6: Evaluation of the combined detection of various indicators in NSCLC.

Discussion

Lung cancer has become a major global public health issue and a key focus of research. In 2022, China reported 1,060,600 new cases of lung cancer and 733,300 deaths related to lung cancer [23]. In recent years, numerous experts and scholars have been engaged in research on the mechanisms of occurrence, patterns of progression, prevention and treatment strategies, and prognostic evaluation of malignant tumors, aiming to improve the effectiveness of early screening and the accuracy of prognostic evaluation for malignant tumors, thereby effectively enhancing patients' quality of life. A large number of existing studies have clearly confirmed that the levels of inflammatory factors are closely associated with the occurrence and development of malignant tumors [24,25].

The role of inflammatory response in tumor initiation, progression, and treatment has attracted considerable attention in the academic community. As early as the mid-19th century, Rudolf Virchow first proposed the theory of the correlation between inflammation and tumors, suggesting that chronic inflammation (such as ulcers and unhealed wounds) could lead to carcinogenesis [26]. This pioneering view laid an important foundation for subsequent research. In 1971, Folkman first proposed the theory that tumor growth depends on angiogenesis [27]. Although it did not directly focus on inflammation, angiogenesis is an important component of the inflammatory response, and inflammatory cells (such as macrophages) can support tumor development by releasing pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor. Folkman's research laid the foundation for the cascade reaction of inflammation-angiogenesis-tumor progression. In 1986, Dvorak [28], through observing the inflammatory characteristics of tumor tissues, pointed out that the tumor microenvironment is highly similar to the wound healing process, and found that tumor cells exploit the inflammatory microenvironment to promote their own growth and survival. This viewpoint provided a critical framework for subsequent research on the role of inflammation in tumorigenesis. In 2011, Hanahan and other scholars expanded the hallmark features of cancer from six in 2000 to ten, discovering that inflammation promotes the acquisition of core hallmark capabilities of cancer cells-such as proliferation [29], invasion, and immune evasion-by modulating the tumor microenvironment [30], playing a key role in the initiation, progression, metastasis, and prognostic evaluation of tumors. In 2017, the Suarez-Carmona team continued the classic view that neoplasms are wounds that never heal [31], emphasizing that chronic inflammation is one of the important characteristics of neoplasms. In 2022, Hanahan[32]updated the cancer hallmarks to 14 items, emphasizing that inflammation drives tumor progression through epigenetic regulation and metabolic reprogramming.

Compared with single inflammatory indicators, AISI, SIRI, and MLR comprehensively assess the immune and inflammatory status of the tumor microenvironment by integrating neutrophil, platelet, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts, and play a significant role in key processes such as tumor invasion and metastasis, immune escape, and treatment resistance. Hu et al s teamfound that NSCLC patients with low SIRI had a longer median overall survival (OS) than NSCLC patients with high SIRI. Rice, et al. found that a low SIRI value was significantly associated with longer disease-free survival (PFS) [16,16,19]. TANG et al. team confirmed that SIRI is an independent prognosis factor for PFS and OS, and the median OS and median PFS of patients in the high SIRI group were significantly lower than those in the low SIRI group [20,21]. Ma et al. used the Cox proportional hazards model to confirm that AISI was a risk factor for OS and PFS [17]. The Phan team found that patients with high pre-treatment MLR had a lower median PFS than patients with low pre-treatment MLR [18]. Zhou et al. confirmed that a low Monocyte-Lymphocyte Ratio indicated decreased OS and PFS in patients with NSCLC, that is, a high MLR indicated decreased OS and PFS in patients with NSCLC [22].

In this study, we found that SIRI, AISI, MLR, and their combined indicators are of great value in predicting the prognosis of NSCLC patients. In terms of single-indicator prediction, the predictive value of SIRI (AUC = 0.762) is higher than that of AISI (AUC = 0.7615) and MLR (AUC = 0.7496). For the combined prediction of multiple indicators, the combined prediction effect of AISI and MLR is the best (AUC = 0.7735). According to the cut-off values of SIRI, AISI, and MLR, the enrolled patients were divided into low-index groups and high-index groups. It was found that the 6 subgroups (high/low SIRI groups, high/low AISI groups, and high/low MLR groups) had statistically significant differences in the prognosis of NSCLC patients (all P < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, or diabetes (all P > 0.05). However, there was a statistically significant difference in gender between patients in the low MLR group and those in the high MLR group (P = 0.029), which is consistent with the view put forward by Li et al. that “MLR has significant differences between different gender groups”. The other subgroups showed no statistically significant differences in gender (all P > 0.05) [32-34].

In summary, the AISI, SIRI, and MLR are important indicators for evaluating the prognosis of patients with NSCLC. Currently, peripheral blood cell count has become a commonly used testing method due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and rapidity. The SIRI, AISI, and MLR not only reflect the inflammatory and immune status of the body but can also be used for multi-index combined evaluation of the prognosis in patients with NSCLC, providing a novel diagnostic approach for clinical diagnosis and treatment. However, this study has certain limitations. Due to its single-center design and relatively small sample size, data collection may be subject to selection bias, and there were missing data during the follow-up process, resulting in incomplete collection of prognosis information such as OS and PFS for some patients. Therefore, the generalizability of its conclusions, as well as the in-depth application value and reference ranges of the related indicators, still require further exploration and validation through multicenter joint studies and expanded sample size clinical trials.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contribution

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hohhot First Hospital (IRB2024323). All participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Funding by National Health Commission of China Medical Artificial Intelligence Clinical Application Research Project (No: YLXX24AIA023).

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, et al. (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries CA Cancer J Clin 68: 394-424.

- Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, et al. (2024) Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. Journal of the National Cancer Center 4: 47-53.

- Reu S, Huber RM (2017) Small cell lung cancer. Onkologe 23: 340-346.

- Shen Y, Liu Z, Chen Y, Shi X, Dong S, et al. (2025) Candidate Biomarker of Response to Immunotherapy in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Current Treatment Options in Oncology 26: 73-83.

- Herbst R S, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C (2018) The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 553: 446-454.

- Aros CJ, Paul MK, Pantoja CJ, Bisht B, Meneses LK, et al. (2020) High-Throughput Drug Screening Identifies a Potent Wnt Inhibitor that Promotes Airway Basal Stem Cell Homeostasis. Cell Reports 30: 2055-2064.

- Couraud S, Zalcman G, Milleron B (2012) Lung cancer in never smokers - A review. European Journal of Cancer 48: 1299-1311

- Kenfield SA, Wei EK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA (20080) Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer. Tobacco Control 17: 198-204.

- Muscat JE, Stellman SD, Zhang ZF, Neugut AI, Wynder EL, et al. (1997) Cigarette smoking and large cell carcinoma of the lung. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 477-480.

- Banna G L, Signorelli D, Metro G, Galetta D, De Toma A, et al. (2020) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in combination with PD-L1 or lactate dehydrogenase as biomarkers for high PD-L1 non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line pembrolizumab. Translational Lung Cancer Research 9: 1533-1542.

- Diakos CI, Charles KA, Mcmillan DC, Clarke SJ (2014) Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncology 15: 493-503.

- Petrova MP, Donev IS, Radanova MA, Eneva MI, Dimitrova EG, et al. (2020) Sarcopenia and high NLR are associated with the development of hyperprogressive disease after second-line pembrolizumab in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 202: 353-362

- Simonaggio A, Elaidi R, Fournier L, Fabre E, Ferrari V, et al. (2020) Variation in neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as predictor of outcomes in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) and non-small cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) patients treated with nivolumab. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy 69: 2513-2522.

- Zhang Z, Zhang F, Yuan F, Li Y, Ma J, et al. (2020) Pretreatment hemoglobin level as a predictor to evaluate the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology12: 1758835920970049.

- Hu M, Xu QH, Yang SY, Han S, Zhu Y, et al. (2020) Pretreatment systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) is an independent predictor of survival in unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy: a two-center retrospective study. Annals of Translational Medicine 8: 1310.

- Li S J, Yang Z, Du H, Zhang W, Che G, et al. (2019) Novel systemic inflammation response index to predict prognosis after thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery: a propensity score-matching study [J]. Anz Journal of Surgery 89: 507-513.

- Ma MT, Luo MQ, Liu QY, Zhong D, Liu Y, et al. (2024) Influence of abdominal fat distribution and inflammatory status on post-operative prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 150:111.

- Phan TT, Ho TT, Nguyen HT, Nguyen HT, Tran TB, et al. (2018) The prognostic impact of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with EGFR TKI. Int J Gen Med 11: 423-430.

- Rice SJ, Belani CP (2021) Diversity and heterogeneity of immune states in non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer. Plos One 16: 260988.

- Tang CH, Zhang M, Jia HY, Wang T, Wu H, et al. (2024) The systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) predicts survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy and the construction of a nomogram model. Frontiers in Immunology 15: 1516737.

- Topkan E, Selek U, Kucuk A, Haksoyler V, Ozdemir Y, et al. (2021) Prechemoradiotherapy Systemic Inflammation Response Index Stratifies Stage IIIB/C Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients into Three Prognostic Groups: A Propensity Score-Matching Analysis. Journal of Oncology 23: 6688138.

- Zhou Y, Liu X, Wu BW, Li J, Yi Z, et al. (2025) AGR, LMR and SIRI are the optimal combinations for risk stratification in advanced patients with non-small cell lung cancer following immune checkpoint blockers. International Immunopharmacology 149: 114215.

- Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, et al. (2024) Cancer incidence and mortality in China. J Natl Cancer Cent 4: 47-53.

- Tomita M, Ayabe T, Nakamura K (2018) The advanced lung cancer inflammation index is an independent prognostic factor after surgical resection in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer [J]. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery 26: 288-292.

- Proto C, Ferrara R, Signorelli D, Russo GL, Galli G, et al. (2019) Choosing wisely first line immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): what to add and what to leave out. Cancer Treatment Reviews 75: 39-51.

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A (2001) Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357: 539-545.

- Folkman J (1971) Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med 285: 1182-1186.

- Dvorak HF (1986) Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med 315: 1650-1659.

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100: 57-70.

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 144: 646-674.

- Suarez-Carmona M, Lesage J, Cataldo D, Gilles C (2017) EMT and inflammation: inseparable actors of cancer progression. Molecular Oncology 11: 805-823.

- Hanahan D (2022) Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discovery 12: 31-46.

- Li Y, Liu Y, Zhou C, Zhang Z, Zuo X, et al. (2021) Monocyte/lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of 30-day mortality and adverse events in critically ill patients: analysis of the MIMIC-III database. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 33: 582-586.

- Meng X, Chang Q, Liu Y, Chen L, Wei G, et al. (2018) Determinant roles of gender and age on SII, PLR, NLR, LMR and MLR and their reference intervals defining in Henan, China: A posteriori and big-data-based. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis 32: 22228.

Citation: Liu C, Yuan Z, Zhang W, Guo J, Mao Y (2026) Relationship Between Preoperative SIRI, AISI, and MLR Levels and Prognosis in Patients with NSCLC: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Pulm Med Respir Res 12: 097.

Copyright: © 2026 Chengpeng Liu, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.