Social Implications of Working in Hospice Conditions

*Corresponding Author(s):

Trylinska-Tekielska EWyzsza Szkola Rehabilitacji, Ul. Kasprzaka 49, 01-234, Warsaw, Poland

Tel:+ 0039 384 808320,

Email:etek@poczta.onet.pl

Abstract

- Aim: The aim of the study was to investigate the social implications of working in hospice conditions.

- Factors: guilt understood as a long-term state of discomfort , religiousness personal and apersonal; fear of death, described as a multi-faceted phenomenon, ptsd.

- Population: being studied is a hospice team (N = 229).

- Questionnaires: Multidimensional Scale of Death Anxiety, Personal Religiosity Scale, Questionnaire of Guilt, Questionnaire PTSD-K1.

- Conclusion:The group of hospice employees is different from others: fear of the unknown.The group of ordinary volunteers is characterized by: fear of premature death.In the hospice team, the largest percentage of declaring personal religiousness and highest level of guilt feelings is declared by a group of hospice volunteers.The most important result from the research is the fact that in the group of hospice employees, the fear of death (of the unknown) is associated with a sense of guilt as a consequence.

Keywords

Fear of death; Hospice; Medical Personel; PTSD; Religiosity, Sense of Guilt; Volunteer

Introduction

Working in an extreme situation is associated with life-threatening, accompanied by the fear of death. When considering thanatological theories many aspects of the fear of death were taken into account: fear of the appearance of the body after death, fear of apparent death, fear of loved ones and others [1]. People who stay longer in the situation of exposure (work in a hospice) may feel (in an unconscious way) fear of losing their "self”.

Given these considerations, the following question was posed: Are there differences in the type of experienced thanatic anxiety in the hospice Team in the groups studied: hospice volunteer, hospice worker, regular volunteer? It has been assumed that each group may (but need not) display a different type of thanatic fear.( thanatological fear: of dying, of the dead, fear of the destruction of the body, fear of the unknown, fear of the appearance of the body, of the living, of apparent death, fear of premature death)

A hypothesis was formulated:

- H1: There are different types of fear of death in the hospice team. People who are involved in traumatic situations are confronted with the fragility, the instability of life. They relate this to their own faith or start wondering about the causality of this world. Jaworski in the literature on religiousness mentions, among others, two aspects: personal (personal reference to God) and a personal (reference to duty) [2].The following research question posed was: Are there differences in the type of religiosity experienced in the hospice Team in the studied groups: hospice volunteers, hospice workers, regular volunteers?

- H2: The hospice team demonstrates different types of religiosity. It was assumed that an extreme volunteer, as a result of their experiences, would have a personal relationship with God, characterized by a mature attitude. A regular volunteer - due to age, lack of experience and not being in a life-threatening situation - treats many things in a duty-like manner and has not reached full maturity, therefore it was assumed that he or she may manifest an a personal type of religiousness. A professional worker is a person (an individual) who is guided in life and work by acquired knowledge, a sense of duty. They transfer this kind of attitude to other areas of life, so they represent the type of a personal (duty) religiosity. A sense of guilt refers to a situation in which the individual subjectively feels moral anxiety about not performing or not fulfilling a duty. The literature states that a person who has been involved in traumatic events and has had no influence on them often has feelings of guilt. It has been hypothesized that individuals who work in extreme situations may seek to repeat them, to make amends, to "wash away" the burdens (survivor guilt); they take on guilt. In the professional hospice worker, guilt may arise from a duty not fulfilled [3].The following research question was posed: Is there guilt present in the hospice Team in the study group of hospice volunteers, hospice workers, and regular volunteers?

- H3: There are different levels of guilt in the hospice team. It was also assumed that working in thanatological conditions may trigger specific reactions. People who are in dangerous conditions may exhibit PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) symptoms, be so-called secondary victims of trauma [4-6].

- H4: There are differences in the declaration of PTSD symptoms in the hospice team. Background Based on observations and available literature on the subject, factors such as: a sense of guilt understood as a longitudinal state of felt discomfort for not helping subjectively felt et religiosity personal and a personal understood as a person's contact with God or a relationship of having to conform to ideologically religious principles; fear of death described as a phenomenon focused on many aspects - fear of loneliness, being buried in the ground, leaving people [6, 2,1]. Other features influencing the choices of this type of work were also taken into account: thanatic anxiety and its types, personal/nonpersonal religiosity, guilt, mood [1-3], [6-8]. It was also assumed that working in thanatological conditions may trigger specific reactions, behaviors that are not without significance for the formation of the psyche. It was also assumed that the type of religiosity may be a predicator of specific activities. The sense of guilt of the survivor (why I survived it and not the one who died). Therefore, it was assumed that both employees and volunteers may feel guilty [2-3]. Extreme conditions are conditions in which you are a witness, a participant in an accident or a victim of a threat to life or death. It is connected with the consequences lasting over time and determining our behavior [3,9].Research methodology - description of statistical procedures. The following research techniques were used in this study: Hoelter's Multidimensional Fear of Death Scale adapted by Makselon [1]. The scale contains 42 statements concerning fear of death. The respondent (subject) answers according to a 7-point scale whether he/she agrees with a given statement. The scale contains a key that estimates which type of fear of death is dominant in the respondent:

- Fear of dying

- Fear of the dead

- Fear of the destruction of the body

- Fear for the living

- Fear of the unknown

- Fear of apparent death

- Fear about body appearance

- Fear of early death

Description of the adaptation and reliability and accuracy can be found in Multidimensional Scale of Death Anxiety by Hoelter in the adaptation of Makselon [1] high reliability, rtt = 0.74. Personal Religiousness Scale developed by Jaworski [2].It examines two types of religiosity - personal religiosity and a personal religiosity. Personal religiosity is understood as an inner experience of contact with God, having a personal character. A personal religiosity is its opposite - it means a material, object-like dimension. Description of the test construction, reliability, accuracy can be found in Psychological correlates of personal religiosity [2]. Guilt Questionnaire (GQ) developed by Kofta et al [6]. It contains 42 unfinished sentences and two options (a and b) to complete them. The subject relates to the content by answering what he or she feels, is of the opinion or thinks at the very moment he or she is taking the test, rather than what he or she should think, be of the opinion or feel. They choose the option that characterizes them - the one that is their personal belief. The construction and psychometric characteristics of the GQ are described in the study of Kofta et al. [6]. The GQ questionnaire is modelled on the questionnaire measuring guilt by D. Mosher's (FCGI - Forced-Choice Guilt Inventory). The theoretical model on the basis of which the questionnaire was constructed is based on the operationalization of theoretical assumptions that guilt is a permanent element of personality, a regulator of social behavior, a self-control mechanism motivating prosocial behavior. As an element embedded in personality, it has a relatively constant power of influence [6]. The individual is motivated to take action for the benefit of other people. Questionnaire PTSD-K by Zawadzki et al. [10]. The inventory is used to assess the post-traumatic stress disorder defined by symptoms according to the DSM-IV textbook. Description of the study group. The study was conducted as a survey research for exploratory research on volunteer environment. 229 people participated in the study. They were divided into three groups. The first group consisted of hospice volunteers. The second group consisted of people who worked professionally in extreme situations, the so-called hospice workers. Both groups worked in an extreme situation, defined as a situation in which the individual is a participant, victim, and witness to a death threat [3]. The third group were volunteers who offered their help in ordinary conditions, where there was no threat to life either for them or for the people they were helping. Problems of own research Based on the results of a survey of a group of hospice volunteers working in contact with death as well as hospice workers and regular volunteers, the following questions emerged: What factors influence the willingness or necessity to be in extreme conditions and what are the consequences of working in these conditions? An attempt was made to consider the most common problems, their constancy, variability, and saturation power. The starting point for the research was to pay attention to factors related anxiety of death, religiosity, feeling guilty, PTSD. Guilt, and fear of death and religiosity were treated as external variables that (from the point of view of social evaluation) have a strong emotional impact. Strong emotions of an unfavorable character for an individual tend to become fixed and lead to fixed specific behaviors. They influence choices, decision-making. They constitute the "second self". Do they - despite their pejorative vector - have a positive influence on personality formation?

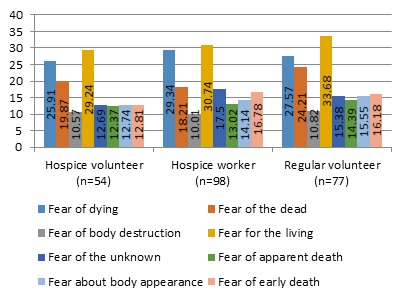

Fear Of Death

The sense of fear of death was operationalized using the Multidimensional Fear of Death Scale by Makselon [1]. The Multidimensional Fear of Death Scale has satisfactory reliability (rtt = 0.74). On the other hand, Izdebski et al verified the internal consistency of the questionnaire, obtaining a Cronbach's α coefficient value of 0.89 [11]. Due to the specificity of the study population of people working under mental stress, occurring both professionally and voluntarily, the questionnaire under discussion was best suited to the study construct. (Tables (1-3)) contain basic statistics characterizing the results obtained in the conducted research separately for each of the compared research groups. Based on the results presented, it can be concluded that in the studied professional groups, the most strongly declared dimension of death anxiety is the fear for the living. Additionally, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test performed to verify the occurrence of differences in the level of perceived fear for the living exceeded the threshold of statistical significance (H (2) = 14.725; p < 0.001). A detailed post hoc analysis using Dunn's nonparametric test with correction for unequal groups and Bonferroni's correction for level of significance determined which occupational groups significantly differed. It turns out that regular volunteers have the highest level of anxiety about the living (M = 33.68, SD = 6.93). Their scores are significantly different from both hospice workers (p < 0.05) and hospice volunteers (p < 0.001). In contrast, the scores of hospice workers, regardless of form of employment, are not significantly different from each other. The second dimension of fear of death that was strongly reported in all groups is fear of dying. Again, statistically significant differences were found for this variable between hospice volunteers, hospice workers, and regular volunteers. The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test exceeded the threshold of statistical significance and was H (2) = 7.298; p < 0.05. Based on a refined post hoc analysis using Dunn's nonparametric test with appropriate corrections, it can be concluded that hospice volunteers have significantly lower (p < 0.05) fear of dying (M = 25.91, SD = 9.21) than hospice workers (M = 29.34, SD = 8.82). In contrast, the level of fear of dying of regular volunteers (M = 27.57, SD = 8.58) was not significantly different from any of the previously mentioned groups. Another strongly experienced dimension of fear of dying by the respondents is fear of the dead. The result of the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was H (2) = 19.870; p < 0.001, which allows us to conclude the presence of statistically significant differences between the compared professional groups. A detailed post hoc analysis using the non-parametric Dunn's test with appropriate corrections allowed us to determine the nature of the differences detected. It turned out that regular volunteers (M = 24.21, SD = 8.71) felt significantly more anxious about the dead than hospice workers (p < 0.001) or hospice volunteers (p < 0.05). In contrast, there were no statistically significant differences in perceived fear of the dead between the latter two groups.

|

|

Fear of dying |

Fear of the dead |

Fear of body destruction |

Fear for the living |

Fear of the unknown |

Fear of apparent death |

Fear about body appearance |

Fear of early death |

|

Mean |

25,91 |

19,87 |

10,57 |

29,24 |

12,69 |

12,37 |

12,74 |

12,81 |

|

Median |

27 |

20 |

10 |

31 |

12 |

12,5 |

12 |

12,5 |

|

Standard deviation |

9,21 |

8,08 |

4,63 |

8,5 |

5,33 |

4,42 |

5,58 |

6,03 |

|

Minimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Maximum |

41 |

36 |

21 |

41 |

26 |

21 |

26 |

28 |

|

Skewness |

-0,855 |

-0,133 |

0,068 |

-1,646 |

0,305 |

-0,689 |

0,16 |

0,12 |

|

Kurtosis |

0,799 |

0,061 |

0,15 |

3,735 |

1,034 |

0,673 |

0,148 |

-0,141 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk test |

0,946** |

0,977 |

0,982 |

0,865* |

0,954** |

0,959 |

0,978 |

0,986 |

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the level of fear of death and of its various dimensions in a group of hospice volunteers (n = 54).

* - result significant at p < 0.001, ** - result significant at p < 0.05.

|

|

Fear of dying |

Fear of the dead |

Fear of body destruction |

Fear for the living |

Fear of the unknown |

Fear of apparent death |

Fear about body appearance |

Fear of early death |

|

Mean |

29,34 |

18,21 |

10,01 |

30,74 |

17,5 |

13,02 |

14,14 |

16,78 |

|

Median |

31,5 |

19 |

10,5 |

33 |

18 |

14 |

13,5 |

17 |

|

Standard deviation |

8,82 |

8 |

5,31 |

8,34 |

7,81 |

5,19 |

7,01 |

6,26 |

|

Minimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Maximum |

42 |

39 |

20 |

41 |

35 |

21 |

33 |

28 |

|

Skewness |

-1,505 |

-0,165 |

0,005 |

-2,14 |

-0,224 |

-0,529 |

0,319 |

-0,699 |

|

Kurtosis |

3,006 |

0,064 |

-0,833 |

5,525 |

-0,382 |

0,086 |

-0,174 |

0,678 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk test |

0,874* |

0,981 |

0,971*** |

0,785* |

0,985 |

0,958** |

0,980 |

0,950** |

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of levels of fear of death and of its various dimensions in a group of hospice workers (n = 98).

* - result significant at p < 0.001, ** - result significant at p < 0.01, *** - result significant at p < 0.05.

|

|

Fear of dying |

Fear of the dead |

Fear of body destruction |

Fear for the living |

Fear of the unknown |

Fear of apparent death |

Fear about body appearance |

Fear of early death |

|

Mean |

27,57 |

24,21 |

10,82 |

33,68 |

15,38 |

14,39 |

15,55 |

16,18 |

|

Median |

29 |

24 |

12 |

35 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

17 |

|

Standard deviation |

8,58 |

8,71 |

4,95 |

6,93 |

6,61 |

4,72 |

8,03 |

5,85 |

|

Minimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Maximum |

42 |

42 |

21 |

48 |

32 |

21 |

41 |

28 |

|

Skewness |

-0,959 |

-0,07 |

-0,007 |

-1,921 |

0,181 |

-0,578 |

0,749 |

-0,165 |

|

Kurtosis |

1,197 |

-0,14 |

-0,453 |

6,763 |

-0,504 |

0,232 |

0,394 |

-0,112 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk test |

0,938** |

0,985 |

0,967*** |

0,860* |

0,984 |

0,950** |

0,949** |

0,987 |

Table 3 Descriptive statistics of the level of fear of death and of its various dimensions in the group of regular volunteers (n = 77).

* - result significant at p < 0.001, ** - result significant at p < 0.01, *** - result significant at p < 0.05.

Interesting results were obtained within the next dimension of death anxiety, which is fear of the unknown. For this variable also, the result of the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test proved to be statistically significant and was H(2) = 17.541; p < 0.001. On the basis of a detailed post hoc analysis using the nonparametric Dunn's test with appropriate corrections, it can be concluded that hospice workers (M = 17.5, SD = 7.81) experience a significantly stronger (p < 0.001) fear of the unknown than hospice volunteers (M = 12.68, SD = 5.33). In contrast, the anxiety level of regular volunteers (M = 15.38, SD = 6.61) was not significantly different from the previously mentioned hospice worker groups. Moreover, for both groups of volunteers, fear of the unknown is one of the lesser experienced fears. Fear of early death is another dimension that significantly differentiates the compared groups of workers. The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was H(2) = 16.765; p < 0.001 and thus can be considered statistically significant. Based on a refined post hoc analysis using the nonparametric Dunn's test with appropriate adjustments, it can be concluded that hospice volunteers (M = 12.81, SD = 6.03) have a significantly lower level of fear of early death than hospice workers (p < 0.001) or regular volunteers (p < 0.01). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the level of perceived fear of premature death between the two groups. The last dimension of fear of death, on which a statistically significant result of the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was obtained (H(2) = 6.189; p < 0.05), thus indicating different results in the compared professional groups, is fear of apparent death. A detailed post hoc analysis using the nonparametric Dunn's test with appropriate corrections determined the nature of the differences detected. It turned out that hospice volunteers (M = 12.69, SD = 4.42) had significantly lower (p < 0.05) fear of apparent death than regular volunteers (M = 14.39, SD = 5.85). In contrast, hospice workers (M = 13.02, SD = 5.19) did not differ significantly in the level of perceived fear of apparent death relative to either group. The only dimensions of fear of death, which did not differ significantly between the compared groups of professionals, were fear of body destruction and the least felt by all respondents fear of body appearance, for which the Kruskal-Wallis test results did not exceed the significance threshold and amounted to, respectively, H(2) = 1.053; p = 0.591 and H(2) = 1.053; p = 0.591). Considering the specificity of the study population, i.e., people working under mental stress both professionally and voluntarily, who had already been involved in hospice work for a long time at the time of the study, the results obtained seem to be justified. Figure 1. provides a visualization summarizing the variation in results discussed.

Figure 1: Graphic illustration of differences in the levels of the eight dimensions of perceived fear of death between the employee groups studied.

Figure 1: Graphic illustration of differences in the levels of the eight dimensions of perceived fear of death between the employee groups studied.

Based on the research conducted and after analyzing the results obtained, it can be concluded that:

H1: There are different types of fear of death in the hospice team has been confirmed.

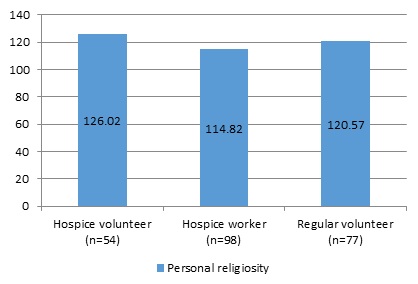

Level Of Personal Vs. Apersonal Religiosity

Jaworski Personal Religiousness Scale was used to measure the intensity of the personal dimension of religiousness [2] (Table 4).

|

|

Hospice volunteer |

Hospice worker |

Regular volunteer |

|

Mean |

126,02 |

114,72 |

120,57 |

|

Median |

133,00 |

119,00 |

129,00 |

|

Standard deviation |

31,31 |

28,12 |

27,44 |

|

Minimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Maximum |

156 |

162 |

158 |

|

Skewness |

-2,634 |

-1,573 |

-1,674 |

|

Kurtosis |

8,429 |

4,595 |

4,033 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk test |

0,723* |

0,890* |

0,863* |

Table 4. shows the basic statistics characterizing the results obtained in the conducted research separately for each of the compared research groups.

* – significant result at the level of p < 0,001.

Based on the results obtained it can be observed that in the group of hospice volunteers the average level of personal religiosity is the highest (M=126.02), but there is also the highest variation in the results here (SD = 31.31). On the other hand, in the group of hospice volunteers, the mean level of personal religiosity is slightly lower (M=120.57) and there is the smallest, yet still large, within-group variation in scores (SD=27.44). Among the hospice workers, the mean level of personal religiosity is the lowest (M=114.72), but there is also a large variation in the results here (SD=28.12). The observed variation in scores is also related to the wide range of scores obtained in each of the study groups. Moreover, all three distributions of the variable are characterized by significant left skewness as evidenced by the negative skewness coefficients. It means that results above the mean of their distributions dominate in the studied groups. On the other hand, the positive value of the kurtosis coefficient indicates significant leptokurticity of the obtained distributions. Thus, most of the results in the studied groups are close to the mean of their distributions. The discussed distortions of the variable distributions in relation to the normal distribution testify to the occurrence of extreme results, which are significantly below the mean.Visualization of the discussed variation of results is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Graphic illustration of differences in personal religiosity between the employee groups studied.

Figure 2: Graphic illustration of differences in personal religiosity between the employee groups studied.

Because the distributions of the analyzed variable in the compared groups did not conform to a normal distribution (all the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test exceeded the threshold of statistical significance), the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to compare the means obtained in the three groups. A statistically significant result was obtained, which was H(2) = 13.312; p < 0.01. It means that at least one mean is different from the others. A detailed post hoc analysis using Dunn's nonparametric test with correction for unequal groups and Bonferroni's correction for the level of significance established the nature of the differences detected. It turns out that hospice volunteers (M = 126.02, SD = 31.31) score significantly higher (p < 0.001) on the personal religiosity scale than hospice workers (M = 114.82, SD = 28.12). In contrast, regular volunteers (M = 120.57, SD = 27.44) do not differ significantly in their level of personal religiosity relative to either group. To sum up, according to the interpretative assumptions of the "Personal Religiosity Scale".[9], the higher the score, the greater the propensity of the respondent to personal religious experiences (personal contact with God). Thus, on the basis of the group averages it can be concluded that hospice volunteers, hospice workers as well as regular volunteers are characterized by religiosity of a personal nature. This speaks for the tendency (inclination) of the respondents to experience personal contact with God. Religiousness, turning to God has an intracontrolled character, external conditions do not determine the relation to God, do not change the relationship with God. The smallest details of life are manifestations of the existence of God and experiencing Him. Based on the results obtained, it can be concluded that the hypothesis H2: There are different types of religiosity in the hospice team - it has not been confirmed. The entire study population shows the same type of religiosity.

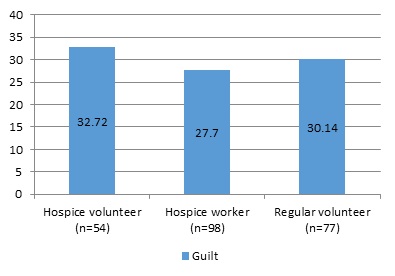

Level Of Guilt

To measure the level of guilt, we used the Guilt Questionnaire developed by Kofta et al. The tool is used to examine "the personality mechanism that determines the frequency of appearance, intensity, and duration of the persistence of guilt as a temporary state of the subject". Guilt is considered to be a factor responsible for a person's moral behavior, a formed capacity for self-punishment. The authors of the questionnaire assumed that the sense of guilt is an important component of the mechanism of human self-control, which "determines the ability of the individual to modulate and suppress their own impulses, defer their gratification in time and adjust the forms of their behavior to social requirements". According to the authors of the questionnaire, guilt understood as a personality dimension should be manifested not only in behaviors related to transgression of norms, but also in attitudes toward other people, generalized judgments about the world and social institutions [6]. (Table 5) shows the basic statistics characterizing the results obtained in the conducted research separately for each of the compared research groups.

|

|

Hospice volunteer |

Hospice worker |

Regular volunteer |

|

Mean |

32,72 |

27,70 |

30,14 |

|

Median |

34,00 |

30,00 |

30,00 |

|

Standard deviation |

7,10 |

8,43 |

7,28 |

|

Minimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Maximum |

42 |

42 |

43 |

|

Skewness |

-2,057 |

-0,791 |

-1,180 |

|

Kurtosis |

7,470 |

0,473 |

3,455 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk test |

0,850* |

0,954** |

0,922* |

Table 5: Descriptive statistics for guilt levels among hospice volunteers (n = 54), hospice workers (n = 98) and regular volunteers (n = 77).

* - significant result at the p < 0.001 level,, ** - significant result at the p < 0.01 level.

Based on the results, it can be observed that the hospice volunteer group had the highest mean level of guilt (M = 32.72, SD = 7.10). Slightly lower mean scores were obtained in the group of regular volunteers (M = 30.14, SD = 7.28) and the lowest mean level of guilt was obtained in the group of hospice workers (M = 27.70, SD = 8.43). In all the studied groups the obtained distributions of the results turned out to be strongly left-skewed as evidenced by the negative values of the skewness coefficients (Figure 3). This means that the results are dominated by those above the mean of their distributions. On the other hand, positive values of kurtosis coefficients indicate that most of the results are concentrated around the mean of their distributions, thus the obtained distributions are significantly leptokurtic.

Figure 3: Graphic illustration of differences in levels of guilt between the employee groups studied.

Figure 3: Graphic illustration of differences in levels of guilt between the employee groups studied.

Because the distributions of the analyzed variable in the compared groups did not conform to a normal distribution (all the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test exceeded the threshold of statistical significance) and because of the unevenness of the compared groups, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to verify the presence of differences in the means. A statistically significant result was obtained, which was H(2) = 16.098; p < 0.001. It means that at least one mean differs from the others. Detailed post hoc analysis using Dunn's nonparametric test with correction for unequal groups and Bonferroni's correction for the level of significance determined the nature of the differences detected. It turns out that hospice volunteers (M=32.72, SD= 7.10) have significantly higher (p < 0.001) levels of guilt than hospice workers (M=27.70, SD=8.43). In contrast, regular volunteers (M=30.14, SD=7.28) do not differ significantly in their levels of guilt relative to either group. In conclusion, the level of guilt of hospice volunteers, regular volunteers, and hospice workers should be considered high. This means that past experiences are, in their subjective view, aggravating. A person with a high level of guilt feels that he or she could have done certain things better, that the things he or she did do were inadequate, and that he or she felt that the things he or she did were inadequate. The obtained results and their analysis confirm the hypothesis.

H3: There are different levels of guilt in the hospice team.

A hospice volunteer reports that they have a high level of guilt.

A hospice employee reports a high level of guilt.

The ordinary volunteer does not show a high sense of guilt.

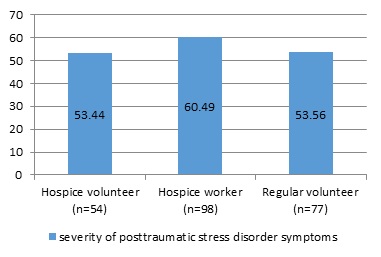

Level Of Severity Of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity was measured using the clinical version of the PTSD Questionnaire by Zawadzki et al. This tool makes it possible to diagnose the presence of PTSD (Table 6), according to the criteria for symptoms described in the DSM-IV manual. The questionnaire has satisfactory accuracy as well as reliability - the authors obtained the coefficient of Cronbach’s α equals 0.90 [10].

|

|

Hospice volunteer |

Hospice worker |

Regular volunteer |

|

mean |

53,44 |

60,49 |

53,56 |

|

median |

54,00 |

56,50 |

56,00 |

|

standard deviation |

26,53 |

20,55 |

30,13 |

|

minimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

maximum |

109 |

116 |

115 |

|

skewness |

-0,477 |

0,269 |

-0,461 |

|

kurtosis |

0,385 |

1,658 |

-0,255 |

|

Shapiro-Wilk test |

0,917** |

0,918* |

0,916* |

Table 6: shows the basic statistics characterizing the results obtained in the conducted studies separately for each of the compared groups of employees.

* – result significant at the p < 0.001, ** - result significant at the p < 0,01.

Based on the results obtained, it can be noted that in the group of hospice workers the average level of severity of posttraumatic stress disorder is the highest (M = 60.49), while both groups of volunteers obtained slightly lower averages, but very close to each other. For all employee groups, there is great variation in the scores obtained, as indicated by both the ranges of scores obtained and the size of the standard deviations. For the hospice worker group, the resulting distribution of scores is slightly right skewed, as indicated by the positive value of the skewness coefficient. On the other hand, the positive value of the kurtosis coefficient indicates a significant slenderness of the distribution. Thus, most of the results oscillate around the mean. In the group of hospice volunteers, the negative value of the skewness coefficient indicates that the distribution obtained is negatively skewed. However, visual analysis of the histogram allows us to conclude that this is the result of a large percentage of people who scored 0 (11%). After excluding them from the analysis, the distribution of the results turns out to be slightly shifted towards low scores. The positive kurtosis coefficient, on the other hand, indicates a clustering of scores around the mean of the distribution. The distribution of results obtained in the group of regular volunteers is left skewed and platocurtic. However, this distortion is due to the influence of the highest percentage of people who obtained a score of 0, indicating that they did not experience the effects of PTSD (17%). When this group was excluded from the analyses, the resulting distribution was found to be slightly positively skewed and leptokurtic. The discussed distortions of distributions in all groups mean that they included persons who do not experience PTSD as well as persons who can be diagnosed with it. A visualization of the discussed variation in results is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Graphic illustration of differences in levels of severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among the employee groups studied.

Figure 4: Graphic illustration of differences in levels of severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among the employee groups studied.

Because the distributions of the analyzed variable in the compared groups did not conform to a normal distribution (all the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test exceeded the threshold of statistical significance) and because of the heterogeneity of the variance (Levene's test also exceeded the threshold of statistical significance, F(2.226) = 4.363; p < 0.05), the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to compare the means obtained in the three groups. The result was H(2) = 1.423; p = 0.491, which thus did not exceed the threshold of statistical significance. Therefore, there is no basis to reject the assumption that the groups of hospice volunteers, hospice workers, and regular volunteers compared with each other do not differ in their mean levels of posttraumatic stress disorder severity. In summary, the entire study population (hospice volunteer, hospice professional worker, and regular volunteer) reported experiencing PTSD symptoms at an average level. With that said, the hospice worker group has the highest percentage of individuals who admit to having existing posttraumatic experiences at all. On the basis of the obtained results concerning post-traumatic experiences in the examined hospice team, it can be concluded that the hypothesis put forward at the beginning:

H4 : There are differences in the declaration of ptsd symptoms in the hospice team –was confirmed

A hospice volunteer has symptoms of PTSD.

A hospice worker has symptoms of PTSD.

Normal volunteer does not show any symptoms of PTSD.

Discussion

Based on research conducted on important variables such as guilt, fear of death and religiosity within the hospice team and the differences in their experience among hospice volunteers, hospice Staff and lay volunteers it can be said that research has been conducted on the condition of the hospice volunteers (who is often seen as a trusted confidant of the patient). The role of hospice volunteers in helping patients is associated with guilt issues [12]. A study discussing different approaches to volunteer motivation and linking them to the four areas of belonging. Using the ABCE model: affiliation (A), beliefs (B), career development (C) and egoistic (E) are addressed by Butt et al.[13]. Characteristic sources of motivational meaning differ among volunteers working in church, hospice and secular context [14]. Coping strategies (in hospice work situations) included behaviors ranging from staying away from the patients religious belief, to realizing that death was a merciful end and was not necessarily painful [15]. Yoga practitioners were found to consistently experience lower fear of death [16]. All rated the training highly. All training programs were treated as a self-reflection on personal spirituality [17]. The topic of mental health and fear of death of paid hospice workers was addressed by Zana et al.[18]. The purpose of the study was to compare Hungarian hospice volunteers with employees in terms of attitudes and fear of death mental health [18]. Feeling comfortable in the face of death and communicating with the patients at the end of life are important attributes of palliative care. The development of a hospice volunteer program to teach these attitudes and skills to preclinical medical students was described by Stecho et al. [19]. Based on a review of the literature on the subject [18], it can be concluded that factors such as tanatic fear may be predictors of both guilt and, as research has shown [19], stimulate an increase or decrease in religiosity. In the current situation of global threats (pandemic-Covid19, war) populations are exposed, hence the need to predict the effects of human behavior and to prepare preventive measures [20-21].

Conclusion

- In the hospice team there are various types of thanatic fear.

- The group of hospice employees is different from others: fear of the unknown.

- The group of ordinary volunteers is characterized by: fear of premature death.

- The group of hospice volunteers is characterized by: fear for the living

- In the hospice team, the largest percentage of declaring personal religiousness is declared by a group of hospice volunteers.

- In the hospice team, the factors influencing each other and determining the behavior and functioning are:

- in the group of hospice volunteers thanatological anxiety, which stimulates the growth of personal religiosity;

- in the group of hospice employees, fear of death and a sense of guilt increasing or weakening personal religiosity;

- in the group of ordinary volunteers, thanatological fear and a sense of guilt are predictors of the intensity of personal religiosity.

- In the hospice team the highest percentage of posttraumatic symptoms is declared by a group of hospice employees.

- A hospice team is a group of people who (regardless of their motivation to work under exposure conditions) are constantly in aggravating conditions related to the trauma of dying.

- The most important element that results from the research is the fact that in the group of hospice employees, the fear of death (of the unknown) is associated with a sense of guilt as a consequence and with a feeling of religiousness.

- On the other hand, in the group of hospice volunteers, the fear of death is associated with an increase in religiosity.

- Worth paying attention to the correlation between thanatic fear, guilt and religiosity depending on the status in the team.

References

- Makselon J (1990) Fear of death. Anthropological implications of thanatopsychological research. Psychological Review 33: 29-38.

- Jaworski R (2011) Personal and impersonal religiousness: A psychological model and its empirical verification (Christian psychology around the World). EMCAPP Journal 1: 46-55.

- Dudek B (2009) Disorder after traumatic stress - PTSD - trauma. Gdansk: GWP; (in Polish).

- Courtois ChA, Ford JD (2020) Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders. Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models 13-30.

- Strelau J (2004) Personality and extreme stress. Gdansk: GWP (in Polish).

- Kofta M, Brzezinski J, Ignaczak M (1977) Construction and psychometric characteristics of the Sense of Guilt Questionnaire (KPW). Psychological Studies 16: 90-108.

- Brown MV (2008) The stresses and coping skills of hospice volunteers. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Science 68.

- Todd AR, Forstmann M, Burgmer P, Brooks AW, Galinsky AD (2015) Anxious and egocentric: How specific emotions influence perspective taking. Journal of Experimental Psychology 144: 374-391.

- Gohm CL, Bauman MR, Sniezek JA (2001) Personality in Extreme Situations: Thinking (or Not) under Acute Stress. Journal of Research in Personality 35: 388-399.

- Zawadzki B, Strelau J, Bieniek A, Sobolewski A, Oniszczenko W (2002) PTSD questionnaire - clinical version (PTSD-K): Construction of a tool for the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Przeglad Psychologiczny 45: 289-315.

- Izdebski P, Jurga M, Kosiol M (2012) Life balance and attitude towards death in late adulthood-Life balance and attitude towards death in late adulthood. Polish Gerontology 20 155–159.

- Kuykendall E (2018) The Opportune Time: The Role of Hospice Volunteers in Helping Patients Deal with Guilt, Regret and Related Spiritual Issues at Ridge Valley Hospice. APHA's Annual Meeting & Expo 14.

- Butt MU, Hou Y, Soomro KA, Maran DA (2017) The ABCE model of volunteer motivation. Journal of Social Service Research 43: 593-608.

- Schnell T, Hoof M (2012) Meaningful commitment: finding meaning in volunteer work. Journal of Beliefs & Values: Studies in Religion & Education 233: 35-53.

- Dein S, Abbas SQ (2005) The stresses of volunteering in a hospice: A qualitative study. Palliative Medicine 19: 58-64.

- Scherwitz L, Pullman M, McHenry P, Gao B, Ostaseski F (2006) A contemplative care approach to training and supporting hospice volunteers: A prospective study of spiritual practice, well-being, and fear of death The Journal of Science and Healing 2: 304-313.

- Gratz M, Paal, P, Emmelmann M, Roser T (2016) Spiritual care in the training of hospice volunteers in Germany. Palliative & Supportive Care 14: 532-545.

- Zana A, Kegye A, Czeglédi E, Hegedus K (2020) Differences in well-being and fear of death among female hospice employees and volunteers in Hungary. BMC Palliative Care 19: 1-8.

- Stecho W, Khalaf R, Prendergas P, Geerlinks A, Lingard L, et al. (2018) Being a hospice volunteer influenced medical students' comfort with dying and death: A pilot study. Journal of Palliative Care 28: 149-156.

- Trylinska-Tekielska E (2019) Working in a hospice - predictors of starting work in a hospice and their consequences in the group of professional workers, hospice volunteers and ordinary volunteers - Psychological Model of the Team working in the conditions of the exhibition. SilvaRerum.

- Trylinska-Tekielska E (2015) Psychologist at the Hospice. Scholar.

Citation: Trylinska-Tekielska E, Wlostowska K, Drewnik M, Tomczyk D (2022) Social Implications of Working in Hospice Conditions. J Hosp Palliat Med Care 4: 015.

Copyright: © 2022 Trylinska-Tekielska E, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.