Social Worker Interpersonal Therapeutic Relationships with Clients (ITR): The Impact of Psychological Mechanisms on Addiction

*Corresponding Author(s):

Shabi AharonBeit Berl College, Beit Berl, Israel

Email:shabiaharon1@gmail.com

Abstract

The present study evaluated the effectiveness of the Interpersonal Therapeutic Relationship (ITR) approach in addiction rehabilitation. This approach, executed by social workers, includes empathy, emotional containment, and empowerment of the patient. The study was conducted among 75 patients treated for eight months in Treatment Communities (TC) for addicts in Israel. The findings, based on quantitative and qualitative methods, show that this approach has a positive effect on the patients’ persistence in drug abstinence, pattern of attachment, and mental well-being. The study found that ITR helped these patients persist in these positive patterns over 8 months. The study sees ITR as a dynamic built-in method based on the therapeutic interpersonal relationship of caregivers as a way of emotional and behavioral change in people with an addiction disorder. It is proposed to conduct further studies that will examine the effectiveness of this method.

Keywords

Emotional containment; Empathy; Empowerment; Drug addicts; Interpersonal Therapeutic Relationship (ITR); Social worker

Introduction

The activity of social workers is designed to change the patients’ patterns of thinking, emotion, and behavior that may be persistently manifested in drug and alcohol abstinence [1]. The existence of an Interpersonal Therapeutic Relationship (ITR) between the therapist and the patient can predict positive outcomes both in the emotional realm and in the cognitive-behavioral aspect, which may be consistently manifested in drug abstinence [2]. The foundations of ITR are attached to humanistic theory [3,4], which aimed to find solutions that helped people give meaning to their lives, realize their abilities, and develop self-efficacy. The humanistic approach has only been partially implemented in the therapeutic field as a stand-alone approach in assisting patients in achieving their goals. Interestingly, although therapists and researchers agree that humanistic approach has many advantages in therapeutic work with disadvantaged populations, this approach is neither defined nor committed when performing therapeutic interventions [2,5]. The present study sought to address this issue while analyzing ITR implementation in a Therapeutic Community (TC) and evaluating the effectiveness of this intervention.

The humanistic approach: Perspective and implementation in ITR

The need to treat crises, disorders, and distress experienced by humans has led to the birth of a variety of clinical, developmental, and social interventions, one of which is the humanistic approach. The uniqueness of the approach, which is one of the oldest therapeutic approaches, is in emphasizing the importance of therapeutic human touch as a platform for giving meaning to patients’ lives [6]. The humanistic approach includes the ability to produce a positive therapeutic atmosphere and honest dialog through empathy and emotional containment, which may be the first steps in building an ITR [7-9]. This requires perseverance and intensity. What are the features required of therapist in running an ITR on the basis of the humanistic approach? According to studies, these features include the initiation of activities leading to closeness with patient with addiction, willingness to help, and an understanding of human needs [9]. Building a secure attachment pattern with the patients is another key concept in ITR [10]. Three main aspects of ITR are discussed below: empathy, empowerment and containment.

Therapeutic empathy as a psychological mechanism driving change

Therapeutic empathy is widely agreed upon as one of the significant therapeutic tools available to therapists to enable self-regulation and building secure attachment in the patient. Although there is no universal definition of the term, there is a consensus that empathy includes an “action” and “ability” by therapists to experience another person’s feelings [11,12]. Therapeutic empathy is aimed to give meaning to the patient's feelings by listening to the patient's explicit and implicit messages [13]. In light of the above, the following questions are asked: How should therapists deal with the patient's barriers? What should the therapists do in a situation where therapeutic empathy does not grow naturally? The answer to these two questions lies in the existence of a continuous physical presence of the therapists in the patient's life [14], as expressed in a setting of a Therapeutic Community (TC). A wide range of studies validate the power of therapeutic empathy in promoting emotional change, awareness, discovery of latent powers in people, and achieving good therapeutic outcomes [15,16]. In general, it can be said that effective empathy will also include processes for validating the patient's identity, guidance, containment, and empowerment [14].

Accepting the patient's feelings: Therapeutic containment

The definition of containment includes the assumption that this emotional therapeutic action allows the therapists to accept the patient's feelings as they are without rejecting them, denying their existence, or throwing them back at the patient inappropriately [2]. It should be emphasized that performing uniform patterns of containment without addressing the patient’s specific emotional characteristics may be ineffective. Containment that is tailored to the needs of the patient may assist in the development of a therapeutic alliance, and the patient’s sense of security [17,18]. The treatment process should include a discussion of the interpretation offered by the therapists to enable accurate and proactive feedback [14]. Therapeutic change is a complex process, which can be initiated by a combination of empathy and containment in addition to a therapeutic presence and may allow the patient to move beyond the boundaries of the self.

Development of self-efficacy: Therapeutic empowerment

Giving meaning to a person's life is an essential idea that exists according to the humanistic approach. The definition of patient empowerment emphasizes promoting the patients’ ability to gain greater control over their life [19]. The patient empowerment processes include additional moves like procedure of motivating the patients to change their lives, increasing their awareness of their condition, and taking the patient out of the ‘in’ to the ‘self’ boundary [20]. Examining the difficulties in assimilating the patient's empowerment reveals that social and cultural barriers may complicate the patient's empowerment process [21,22]. As a rule, motivating the patient from a passive to an active state may promote a sense of meaning and ability.

Attachment patterns

The study examined changes in patients’ attachment patterns. Attachment patterns refer to people’s ability to establish inter-personal relationship with other people [23,24]. Insecure attachment is characterized by anxiety and avoidance of people, whereas secure attachment is characterized by the ability to make safe connections with people [10]. Children with insecure attachment patterns tend to be avoidant and self-isolated during childhood and adulthood. These children could experience loneliness and even develop extreme behaviors such as violent behavior and addiction [24]. On the other hand, children and adults with good social adaptability typically develop a secure attachment pattern that enables them to restore emotional balance and self-efficacy upon adversity [24,25]. Studies that addressed the question of whether people's attachment patterns can be changed, have shown that the transition from an insecure attachment pattern to a secure attachment pattern is indeed possible [24,26]. The factors that can contribute to the transition of a person to a secure attachment are therapeutic factors which include support, a safe patient environment, empathy and containment [25,26]. It was therefore hypothesized in the present study that ITR would have a beneficial effect on changing the attachment pattern of research participants which would lead to persistence in drug and alcohol abstinence.

Mental well-being

The changes in mental well-being of the patients were also examined in a study. Mental well-being includes two aspects: high (good) mental well-being and low mental well-being (bad). Positive mental well-being includes a positive state of mind, such as life satisfaction [27,28]. Low mental well-being includes a negative state of mind and low expectations of the future. In the context of drug abuse, mental well-being involves a vicious cycle that is sometimes difficult to break. On the one hand, a low sense of well-being resulting from personal distress and negative effects of the environment may in itself contribute to addiction, and on the other hand, addiction to psychoactive substances may contribute to low mental well-being, which makes it difficult for people to cope with their problems. Positive factors that can contribute to high mental well-being include an objective change in one’s condition, such as integration into employment, dealing with the problem of addiction, and developing new social relationships. These changes may occur under the influence of therapeutic factors such as therapeutic empathy and empowerment of the person [27,29]. In the present study, it was hypothesized that ITR would have a parallel positive effect on both the improvement of mental well-being.

The present study

The study examined the effectiveness of the psychological mechanisms implemented in ITR that includes empathy, containment, and empowerment throughout 8 months of social worker intervention with patient with a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) in TC. The study assessed the effectiveness of the program in terms of attachment pattern, mental well-being, and persistence in abstinence from drugs and alcohol.

For this purpose, the following hypotheses were tested:

- Following ITR intervention, study participants with an insecure attachment pattern will develop a secure attachment pattern. Study participants with a secure attachment pattern at the time of entry to TC will maintain this secure attachment pattern following the treatment

- ITR intervention will have a positive effect on the participants’ level of well-being, increasing the level of well-being among patients with initial low mental well-being and maintaining well-being levels among patients with initial high mental well-being

- ITR intervention will have a positive effect on the participants' persistence in abstinence from drugs and alcohol

Methodology

Participants

The study was conducted in 2019among 75 patients with a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) in Israel [30]. Study participants were selected from an existing group of patients who stayed for eight months in one of seven TC located all over Israel. A TC is an inpatient comprehensive facility which provides the patients therapeutic, medical, occupational, social, educational and community responses [31,32]. Joining the TC, which is funded by the Israeli government, is done voluntarily. TC patients are between the ages of 18-55. The average age of the participants was 40. The demographic characteristics show that 90.7% of the patients were men, and most of them had participated in outpatient treatment programs in the past but were unable to persist in drug abstinence. Near half (45%) of the participants had previously been in prison for committing criminal offenses and drug trafficking (N = 33). Most of the participants used the following psychoactive substances: cannabis (65%), heroin (34%), and alcohol (61%) [30]. It should be noted that among the 75 patients recruited in this study, 39 patients dropped out of TC during the first two months of their stay due to difficulties adapting to the community and personal difficulties, and 36 patients completed the treatment. The data presented represent the patients who completed the program.

Measures

Measures

The research was conducted as a longitudinal study which examined patients' attachment pattern, mental well-being, and addiction status at two time points: upon arrival at the TC and eight months later, upon completion of the program. In Israel there is no additional TC. As a result, it was not possible to conduct a study with a control group. The following questionnaires were used: The Participants' Attachment Pattern Questionnaire that examine whether the study participants have the ability to form social connections [33]. The questionnaire included 36 items on a 7-point Likert scale between strongly agreeing (1) and strongly disagreeing (8). This questionnaire has been used in many studies and showed high validity in the present study (a = 0.89). The Mental Well-being questionnaire [34], examine the level of optimism and life satisfaction of the study participants included 14 items on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from negative (1) to positive (6). This questionnaire has been used in many studies as well, with high validity in the present study (a =0.91). The questionnaire: “characteristics and roles of social workers” includes the variables empathy, containment and empowerment also filled in by the study participants. These variables were presented as defined in the humanistic and the emotion-focused theories [4,14].

In this questionnaire, the study participants reported about the influence of the variables on emotional changes experienced during the TIP. The questionnaire was delivered after 4 and 8 months of participants in TIP. Additional questionnaire was used in the study that examined the status of drug abuse among the participants, the ASI questionnaire [35]. In the second phase of the study, interviews with the study participants were conducted based on the Activation of the Characteristics: Therapeutic-empathy, Empowerment, and Containing and the Roles of Social Workers. The interviews were conducted individually, in a designated place in the therapeutic community under the guidance of a research assistant.

Ethical considerations

The patients in the TC who participated in the study did so voluntarily. During the research process, the research assistants answered the questions of the participants before the beginning of the research and distributed to them a document defining the research aims. The research participants subsequently signed an informed consent form. The research process was constantly examined by the research assistants who verified that the participants understood the research questions.

Results

The quantitative and qualitative research findings included emotional and behavioral information about the patients in the drug and alcohol addiction phase and information regarding the rehabilitation process they underwent through the ITR. The information about the patients' condition in the period prior to joining TC revealed that patients described complex difficulties and coping with addiction and difficulty in establishing secure attachment to their social environment. As D., patient with addiction to cocaine, noted, “I have a complete lack of trust in people. I do not trust anyone and do not want to make new connections. Every time I tried to make contact, I was disappointed.” B., addicted to heroin, similarly noted, “I usually met people who did not understand me, did not address my problems, and did not hear what I had to say, so I felt blocked from being able to contact the social worker and hear what she had to say to me. I did not want to be disappointed again.”

Patients presented the meaning of the psychoactive substance for them as helping them cope with the complexities of life. As M., patient with addiction to alcohol for many years, noted, “I did not know how to take care of myself, I had a lot of emotional barriers, I was alone. Later I found a “friend,” the alcohol. The substance helped me at some point overcome these barriers, reduce unhelpful thoughts, and most of all, overcome my loneliness. But it was all for a short time, then I started to get tangled up with my feelings and the feeling of loneliness came back.”

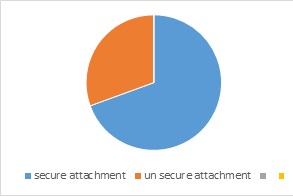

The findings of the study with respect to the effect of the TIP expressed from the questionnaire summary: “characteristics and roles of social workers" which included the variables empathy, containment and empowerment, which filled in by the study participants and information from the qualitative interview [30]. The findings show that 47.2% of the patients who persisted for 8 months in the TC, had a secure attachment pattern when joining the Therapeutic Community (TO). Following the ITR process, 70% of them were with secure attachment pattern (T1) and 30% of them were left with an insecure attachment pattern [30] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The effect of TIP on attachment patterns of the research participants.

Figure 1: The effect of TIP on attachment patterns of the research participants.

In light of the findings, achieving a secure attachment pattern resulted from the interpersonal bonding processes performed by the social workers throughout 8 months of intervention. F., patient with addiction to alcohol, stated, “I experienced confidence in the relationship with the social worker. She gave me support, constant attention, understood my difficulties and made me feel equal.” K., patients with a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) to heroin, noted, “I felt in touch with the social worker [and] that it was the safest place for me. I felt I was capable. She taught me how to connect with others [and] I felt no longer alone. She helped me survive in the community and conveyed her deep trust in me.”

The study also found a positive relationship between ITR processes and high mental well-being after 8 months of intervention. The data that referring to patients who persisted for 8 months in TC showed that most of the study participants (75%) who persisted in treatment (N = 27) reported a high sense of mental well-being, while 25% of the participants reported low mental well-being during their integration into the therapeutic community [30]. Eight months after the therapeutic intervention process (T1), 88% of the participants who persevered in the study persisted in high mental well-being or their mental well-being pattern changed from low to high. The remainder (12%) of the participants were left with low mental well-being [30] (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The effect of TIP on mental well-being of the research participants.

Figure 2: The effect of TIP on mental well-being of the research participants.

The positive change that shown in the data with respect to the pattern of attachment and mental well-being is significant. The ability to both, persevere and positively change these patterns is not self-evident, and to a large extent is a result of the ITR activities. According to the findings, therapeutic relationships that had a positive effect on perseverance in good mental well-being included the assistance of the social worker in removing emotional barriers, the support and acceptance of patients, and processing patients’ hidden emotions. M., patients with a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) to cannabis, noted that “The social worker listened to me all the time, helped me talk about my fears, and taught me how to cope with my inner world. Following the relationship with her, I became much more optimistic about myself.” B., addicted to alcohol and cocaine, noted, "I finally found someone who understood me. The social worker was not judgmental at all. [She] understood my difficulties and why I was depressed many times, talked to me about things I repressed, and taught me how to cope with my helplessness. I believe my future will be better.”

Importantly, 100% of the study participants (N = 36) persisted in abstaining from drugs and alcohol [30]. Persistence of participants in abstinence from drug use over 8 months was ascribed by the participants to the assistance of social workers, allowing them to regain control over their lives and develop awareness of the source of their problems. C., patient with addiction to amphetamines, noted, “The social worker introduced me to a new line of thought, allowed me to work on myself, helped me feel meaningful, and most of all, let me decide about the rest of my life. She presented me with different ways of progressing. It helped me a lot in the process of persevering in the abstinence from drugs to which I have been addicted for many years.” B., patient with addiction, to alcohol and heroin, stated, “With the help of the contact with the social worker, I received practical help, I learned how to solve problems, [and] my whole line of thinking changed. She discovered powers in me that allow me to cope differently with the addiction problem. I am aware of my difficulties and have control over my drug [abuse] problem that I did not have before.”

The findings of the study as emerged from the questionnaires and interviews [30], regarding the effectiveness of ITR and the responses given by the social workers to the many difficulties of the participants supported the research hypotheses and were reflected in all aspects examined: secure attachment pattern, improved mental well-being, and persistent abstinence from substances of abuse.

Discussion

The present study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of the ITR program in TC in the rehabilitation of patients with a Substance Use Disorder (SUD). The main insight derived from the research findings is that the behavioral and emotional change of patient with addiction was not random [30]. The findings were consistent with studies regarding the effect of ITR on the emotional change of the patients, who benefited from the treatment by using it as an engine for gaining control over their lives [20]. The therapeutic relationship in this study enabled a secure relationship between the social worker and the participants and influenced the achievement of behavioral and emotional changes by shaping a supportive emotional climate and building good intimacy [25,30,36,37]. The ITR process helped many patients in coping with difficult conflicts with the rules in the community about the background of their addiction problem and allowed them to develop social capacity, which was new to many of them [38]. Increasing participants’ control over their lives in the TC and developing participants' awareness of the source of their problems led to practical positive outcomes that include, among other things, persistence in drug abstinence [32].

The present study presented the beneficial effect of intensive interpersonal therapy in treatment settings [31,39-41]. To a large extent, during the intervention process, the social workers demonstrated psychological mechanisms that enabled self-regulation and motivation of study participants, driving them from a passive to an active state, as expressed in changing patients’ attachment patterns [42,43]. Approximately 42% of participants were with a secure attachment at the time of joining the TC. It is assumed that ITR contributed to this group persisting in a secure attachment pattern and allowed other patients with an insecure attachment to experience a secure attachment pattern [30]. According to the findings, not all participants experienced a change in attachment patterns and mental well-being [24,27,28]. A possible explanation is that ITR did not develop in some patients due to issues related to patients' personal barriers and social and environmental barriers [40]. The solution to these gaps may lie in locating fractures in treatment, locating patients’ hidden internal resources, and strengthening emotional abilities. Regarding the group of study participants who dropped out of the research during the first two months of their stay in TC, it can be said that this group experienced ITR only initially, and due to the short intervention time it was not possible to establish effective therapeutic relationship.

An analysis of the study findings leads to the conclusion that ITR may be considered as one of the powerful therapeutic tool for developing self-awareness, self-efficacy, and secure attachment among people coping with the illness of addiction.

Conclusion

The findings make it clear therapeutic relationship in itself may influence the development of significant emotional changes in people coping with addiction that could lead to personal development and practical changes. The lesson to be learned from the present study is that ITR may be relevant for treating a variety of distressed populations. The study provides a better understanding of the characteristics of ITR and the factors underlying the effectiveness of this interpersonal therapeutic method.

Limitations

The first limitation is related to the fact that the present study is a longitudinal study with a small group of participants. The study does not allow the use of a control group that could identify more specific factors of emotional changes which may be achieved within the framework of ITR. Another possible limitation is related to the subject of change in the attachment pattern of patients who were with an insecure attachment pattern while joining TC [26]. It should be noted that this finding may contradict studies which indicate that a pattern of attachment formed in childhood will not change during adult life [24]. Since the dropout rate of the participants was 52%, there may be a limit to understanding the quality of impact of the ITR with respect to the dropout group. In addition, the study did not examine the persistence in drug abstinence after the end of treatment, therefore could not comment on the long-term effects of ITR.

Future Studies

Future studies should examine the effectiveness of the ITR method among additional populations in distress. In addition, conducting qualitative studies may give us more in-depth information about the impact of ITR components on emotional and behavioral change among at-risk populations. It is recommended to conduct studies that would compare the effectiveness of ITR to other therapeutic methods among different populations coping with difficulties in their lives.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hepworth DH, Rooney RH, Rooney GD, Storm-Gottfried K, Larsen J-A (2006) Direct social work practice: Theory and skills. Thomson Brooks, Belmont, USA.

- Yalom ID, Leszcz M (2020) The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, Basic Books, New York, USA.

- Rogers CR (1957) The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology 21: 95-103.

- Rogers C (1994) Freedom to learn. Pearson, London, UK.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (2013) Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rdedn). Guilford, New-York, USA.

- Rogers CR (1995) On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin, Massachusetts, USA.

- Norcross JC (2011) Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Berant JH, Obegi E (2010) Attachment-informed psychotherapy research with adults. In: Obegi JH, Berant E (eds.). Attachment theory and research in clinical work with adults. The Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Degnan A, Seymour-Hyde A, Harris A, Berry K (2014) The Role of Therapist Attachment in Alliance and Outcome: A Systematic Literature Review. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 23: 47-65.

- Bowlby J (1988) A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge, London, UK.

- Maibom HL (2012) The many faces of empathy and their relation to prosocial action and aggression inhibition. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Cognitive science 3: 253-263.

- Oxley JC (2011) The moral dimensions of empathy: Limits and applications in ethical theory and practice. Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK.

- Jacobs TJ (2013) The Possible Profession: The Analytic Process of Change. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Greenberg L (2015) Emotion-focused therapy. American Psychological Association, Massachusetts, USA.

- Elliott R, Bohart AC, Watson JC, Murphy D (2018) Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy (Chic) 55: 399-410.

- Wampold BE, Imel ZE (2015) The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2ndedn). Routledge, New York, USA.

- Shaver PR, Schachner DA, Mikulincer M (2005) Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 31: 343-359.

- Mittler P (2000) Working Towards Inclusive Education: Social Contexts. Fulton, London, UK.

- Rappaport J (1981) In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. Am J Community Psychology 9: 1-25.

- Lane STM, Sawaia BB (1991) An experience with favela women: Participate theory research as an operational tool for epistemological premises in community social psychology. Applied Psychology: An international Review 40: 119-142.

- Lefcourt HM (1981) Differentiating among internality. Powerful others and chance. In: Lefcaurt HM (eds.). Research with the locus of control construct (1stedn). Academic Press, New York, USA.

- Rothman J (2007) Multi modes of intervention at the macro level. Journal of Community practice 15: 11-40.

- Bowlby J (1973) Attachment and Loss: Separation, anxiety and anger. Basic books, New York, USA.

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2008) Adult attachment and affect regulation. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR (eds.) Handbook of Attachment, Second Edition: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Meier PS, Donmall MC, Barrowclough C, McElduff P, Heller RF (2005) Predicting the early therapeutic alliance in the treatment of drug misuse. Addiction 100: 500-511.

- Fonagy P, Steele M, Steele H, Higgitt A, Target M (1994) The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 1992. The theory and practice of resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 35: 231-257.

- Blatt SJ (2004) Experiences of Depression: Theoretical, Clinical, and Research Perspectives. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- Diener E (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 95: 542-575.

- Biswas-Diener R, Vittersq J, Diener Ed (2005) Most people are pretty happy, but there is cultural variation: The Inughuit, the Amish, and the Maasai. Journal of Happiness Studies 6: 205-226.

- Shabi A (2021) The Impact of a Therapeutic Intervention Program (TIP) on the Wellbeing and Attachment Patterns of Addicts. Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, Israel.

- De Leon G (2010) The therapeutic community: A recovery oriented treatment pathway and the emergence of a recovery-oriented integrated system. In: Yates R, Malloch MS (eds.). Tackling addiction: Pathways to recovery. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK.

- De Leon G (2015) Therapeutic Communities. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD, Brady K (eds.). The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of substance Abuse treatment (5thedn). American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, DC, USA.

- Ben-Naim S (2007) Emotional regulation during a marital conflict, the moderating role of attachment styles (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Bar-Ilan University, Israel.

- Almog-Ovadia H (2013) The association between the father's drug addiction and the mother's parental functioning and satisfaction (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel.

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP (1980) An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis 168: 26-33.

- Errázuriz P, Constantino MJ, Calvo E (2015) The relationship between patient object relations and the therapeutic alliance in a naturalistic psychotherapy sample. Psychol Psychother 88: 254-226.

- Ackerman SJ, Hilsenroth MJ (2003) A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clin Psychol Rev 23: 1-33.

- Decety J, Jackson PL (2006) A social-neuroscience perspective on empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science 15: 54-58.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (2012) Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, USA.

- Zastrow C (2007) The practice of social work: A comprehensive work text. Thomson Higher, Belmont, USA.

- WHO, (2016) International standards for the treatment of Drug use disorders - Draft for Field Testing. United Nations office on Drugs and Crime, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Park CL (2010) Making sense of the meaning Literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol Bull 136: 257-301.

- Vrugt A, Kaenis S (2002) Perceived self-efficacy, personal goals, social comparison, and scientific productivity. Applied Psychology: An International Review 51: 593-607.

Citation: Aharon S (2022) Social Worker Interpersonal Therapeutic Relationships with Clients (ITR): The Impact of Psychological Mechanisms on Addiction. J Addict Addictv Disord 9: 085.

Copyright: © 2022 Shabi Aharon, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.