Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medical Care Category: Medical

Type: Review Article

Volunteer Assessment Scale (VAS) for Assessing Hospice Workers

*Corresponding Author(s):

Marissa HappDepartment Of Social Work, Aurora University, Aurora, United States

Tel:+1 6304840631,

Email:mhapp@aurora.edu

Received Date: Jun 14, 2019

Accepted Date: Jul 05, 2019

Published Date: Jul 12, 2019

Abstract

The development of the Volunteer Assessment Scale (VAS) and its psychometric characteristics are discussed in part one of the paper. The VAS is shown to be a unidimensional instrument with high reliability for this sample and conditions. It contains eight divisions relevant to volunteerism that are discussed. Several applications for its use of the VAS are given to enhance its utility.

This paper describes the development of the Volunteer Assessment Scale (VAS) which is designed as an instrument for use with hospice volunteers. The first part of the paper presents the psychometric characteristics of the VAS. The second section suggests various applications and uses of the VAS.

Hospice and bereavement workers carry significant stressors but continue to serve. The bio psychosocial model considers the biological, psychological, social, environmental and behavioral aspects of the patient; problems in any of these areas may impact health outcomes and volunteer status. It is important, then, to consider the needs of the hospice and bereavement worker whose unpaid work is often intense and emotionally challenging.

This paper describes the development of the Volunteer Assessment Scale (VAS) which is designed as an instrument for use with hospice volunteers. The first part of the paper presents the psychometric characteristics of the VAS. The second section suggests various applications and uses of the VAS.

Hospice and bereavement workers carry significant stressors but continue to serve. The bio psychosocial model considers the biological, psychological, social, environmental and behavioral aspects of the patient; problems in any of these areas may impact health outcomes and volunteer status. It is important, then, to consider the needs of the hospice and bereavement worker whose unpaid work is often intense and emotionally challenging.

Keywords

Bereavement; Hospice; Volunteers

SAMPLE

The sample consisted of patient care volunteers, working directly with patients receiving palliative care from area hospice agencies, those undergoing chemotherapy treatments at local centers, and bereavement care volunteers, working with individuals, families and groups after death has taken place [1].

When the study was introduced, the active direct service volunteers numbered 70; of these, 62 agreed to be part of this research project. Forty-four (44) completed the VAS. This was a convenience sample of easily accessible participants. It is notable that the sample of 44 respondents consisted of hospice/bereavement volunteers with more than fifteen consecutive years of service.

When the study was introduced, the active direct service volunteers numbered 70; of these, 62 agreed to be part of this research project. Forty-four (44) completed the VAS. This was a convenience sample of easily accessible participants. It is notable that the sample of 44 respondents consisted of hospice/bereavement volunteers with more than fifteen consecutive years of service.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

The Volunteer Assessment Survey (VAS) consists of 32 statements addressing eight specific topics. Participants were instructed to answer yes or no to each statement according to how strongly it reflected (or did not reflect) his or her own beliefs. Internal reliability of the VAS was r = 0.98 and standardization was based upon the sample of 44 volunteers. Item development was established earlier by piloting items from the instrument to 221 social work students’ ages 24 to 67 assessed over several semesters.

BIOLOGICAL STRESSORS

These statements were designed to determine the extent to which the volunteer currently faces serious medical issues or may have concerns about his/her personal state of health. It was designed to also reveal the extent to which the participant’s family history suggests the possibility of serious illness.

PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESSORS

These statements were designed to explore the volunteer’s perceptions of his/her internal emotional condition, the challenges of painful emotions and the degree to which effective self-care skills are being utilized.

SOCIAL STRESSORS

These statements explored the complexities of the volunteer’s human relationships and the degree to which they experience social support on a regular basis.

SPIRITUALITY

These statements determined the extent to which the volunteer considers spirituality personally important and if their own unique faith life includes belief in a God or Higher Power.

BEREAVEMENT/LOSS

These statements discover the extent to which the volunteer has experienced the death of loved ones and the degree to which they are able to have empathy for their clients facing death.

MORTALITY

These statements determine the extent to which the volunteer considers personal end-of life issues and the degree of comfort they feel with human mortality.

VOLUNTEERISM

These statements determine the extent of the participant’s volunteer work, the priority it holds and his/her thoughts on altruism.

FORTITUDE

These statements bring forward the volunteer’s thoughts the meaning of personal suffering, his/her willingness to assist others even while bearing personal burdens and the degree to which they believe they can be useful to others even if they themselves are suffering.

RASCH MEASUREMENT ANALYSIS OF THE VAS

Rasch analysis of the VAS was used to analyze the characteristics of the instrument itself and to determine the misfit of any item beyond a standard deviation of 2.0. The responses to each statement were measured by percentages for each category. A t-test was used to determine the differences in the mean scores between men and women, and ANOVA compared the mean scores within the three age groups and four categories of years of volunteerism.

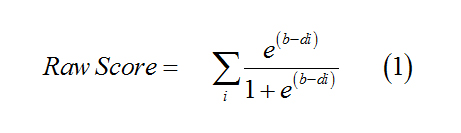

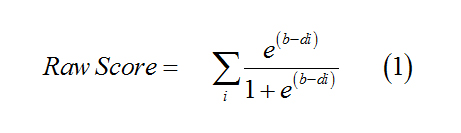

Analysis of the VAS followed the strategies outlined in the Best Test Design by Wright and Stone [2] and utilized computer software in WINSTEPs [3]. Rasch measurement utilizes the Rasch logistic formula (1) to relate the raw scores of the VAS to measures:

Formula (1) can be utilized to analyze the characteristics of the instrument, i.e., item analysis. In this formula, b signifies the person responding and di an item of the VAS. This formula transforms each raw score to a measure. Item and person measures are accompanied by item statistics produced by WINSTEPS software [3].

Item analysis indicates misfit values for INFIT and OUTFIT where INFIT examines misfit close to the score and OUTFIT examines misfit at a distance from the score. The in fit item mean was 1.00 and the outfit mean was 1.03 showing that the item sequence indicated no statistically significant misfit. Item point-biseral coefficients ranged from .01 to .29 with only three coefficients greater, two at .48 and one at .54 indicating no high correlation between any item and the total score.

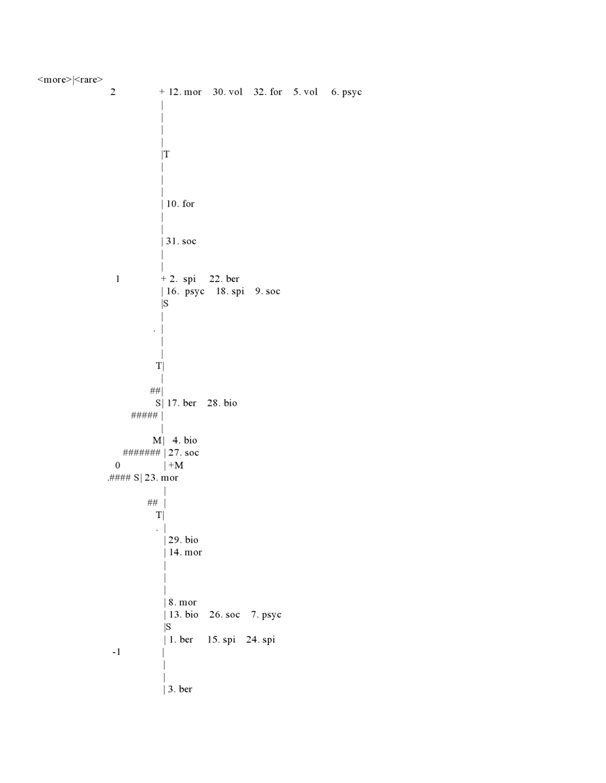

Figure 1 is a map of the VAS. Left of the vertical dividing line is the measured logistic location of each respondent. M is the mean and S and T indicate one and two standard deviations respectively from the mean. Each # indicates two respondents. Each dot indicates one respondent. The distribution of the respondents is very narrow compared to the distribution of the items indicating that the items were relevant to the sample.

Analysis of the VAS followed the strategies outlined in the Best Test Design by Wright and Stone [2] and utilized computer software in WINSTEPs [3]. Rasch measurement utilizes the Rasch logistic formula (1) to relate the raw scores of the VAS to measures:

Item analysis indicates misfit values for INFIT and OUTFIT where INFIT examines misfit close to the score and OUTFIT examines misfit at a distance from the score. The in fit item mean was 1.00 and the outfit mean was 1.03 showing that the item sequence indicated no statistically significant misfit. Item point-biseral coefficients ranged from .01 to .29 with only three coefficients greater, two at .48 and one at .54 indicating no high correlation between any item and the total score.

Figure 1 is a map of the VAS. Left of the vertical dividing line is the measured logistic location of each respondent. M is the mean and S and T indicate one and two standard deviations respectively from the mean. Each # indicates two respondents. Each dot indicates one respondent. The distribution of the respondents is very narrow compared to the distribution of the items indicating that the items were relevant to the sample.

Figure 1: Person and item map of the VAS.

Right of the vertical dividing line are the item locations of the VAS shown by their measured values together with their codes. Figure 1 indicates as a map how the items are located by the measured logistic space between any two items of groups of items.

From the total variance of the measures (scores) of persons at 100%, the VAS accounts for 84.8% of the total variance with only 15.2% unexplained variance. These values were computed from a principal components analysis of the VAS items using WINSTEPS software. In summary, the VAS appears a valid and useful unidimensional instrument with high reliability inasmuch as its internal reliability coefficient was reported at 0.98 for this sample in this application. Item grouping are determined from item content while unidimensionality is determined by the associated probabilities from WINSTEP analysis. Consequentially, a unidimensional scale may contain various categories as does the VAS.

From the total variance of the measures (scores) of persons at 100%, the VAS accounts for 84.8% of the total variance with only 15.2% unexplained variance. These values were computed from a principal components analysis of the VAS items using WINSTEPS software. In summary, the VAS appears a valid and useful unidimensional instrument with high reliability inasmuch as its internal reliability coefficient was reported at 0.98 for this sample in this application. Item grouping are determined from item content while unidimensionality is determined by the associated probabilities from WINSTEP analysis. Consequentially, a unidimensional scale may contain various categories as does the VAS.

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

A t test was conducted for a VAS score difference by sex. For 31 females (mean=83, SD=3.74) and 12 males (mean=83, SD=4.34) and t statistic of 0.34 with p=0.73 against a critical two-tail test of 2.1 was not statistically significant. There was no statistically significant difference between males and females on the VAS.

ANOVA was used to test for VAS score differences for the three age groups and the four groups designating years of service. The VAS scores among the three age groups was not statistically significant with F = 0.002652 and F critical at 1.65 (d.f.=1,34, =0.99). The VAS scores for the four groups by age of service was not statistically significant with F = 0.0259 and F critical at 1.65 (d.f.-1,34, p = 98).There was no statistically significant difference among any of the age groups.

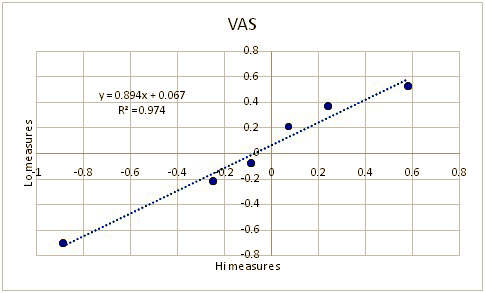

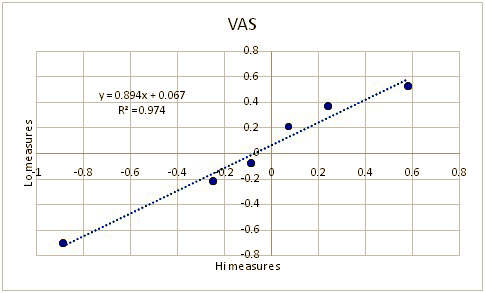

The three highest scores were correlated to the three lowest scores as shown in figure 2 which shows an almost perfect correlation with R2=0.97. This analytical strategy was introduced by Rasch [5] and exemplified by Wright [4] which indicates that VAS measures are clearly linear when the data fit the Rasch logistic model as previously demonstrated. Wright’s presentation, over fifty years ago, (1967) featured two cumulative ogives constructed from test responses (not given here). The first one showed the test scores for two groups clearly differing in their ability as indicated by two clearly separated ogives. The second figure plotted these same scores, but now according to their Rasch “person?free test calibration” measures. In this instance the two ogives were virtually the same.

ANOVA was used to test for VAS score differences for the three age groups and the four groups designating years of service. The VAS scores among the three age groups was not statistically significant with F = 0.002652 and F critical at 1.65 (d.f.=1,34, =0.99). The VAS scores for the four groups by age of service was not statistically significant with F = 0.0259 and F critical at 1.65 (d.f.-1,34, p = 98).There was no statistically significant difference among any of the age groups.

The three highest scores were correlated to the three lowest scores as shown in figure 2 which shows an almost perfect correlation with R2=0.97. This analytical strategy was introduced by Rasch [5] and exemplified by Wright [4] which indicates that VAS measures are clearly linear when the data fit the Rasch logistic model as previously demonstrated. Wright’s presentation, over fifty years ago, (1967) featured two cumulative ogives constructed from test responses (not given here). The first one showed the test scores for two groups clearly differing in their ability as indicated by two clearly separated ogives. The second figure plotted these same scores, but now according to their Rasch “person?free test calibration” measures. In this instance the two ogives were virtually the same.

Figure 2: Plot of VAS high measures to low measures.

Such plots and outcomes are now the classic demonstration of Rasch’s model applied to test data when data fit the model. The differences between the two tests can be divided by the measurement error to produce a standardized difference, and Wright summarizes saying, “These alternative estimates of ability (Figure 1 vs. Figure 2) seem to be aiming at the same thing.” But the first figure and values indicate the impossibility of a relationship while a Rasch model calibration provides an almost perfect replication. The measuring model in the presentation gave the odds of success, Oni by the product of person ability, Zn, and the item easiness, E1 yielding Oni = ZnE1 using Wright’s notation for that time. The probability that a person with ability Zn will succeed on item easiness E1 is ZnE1 divided by one plus the product, Pin = ZnE1/(1+ZnE1) - the Rasch model.

In summary, the mean for all participants showed no significant differences, suggesting a highly homogeneous group even though both sexes were included in the study. The ages of participants ranged from 20 to 60+ and years of service ranged from 15 years to over 25 years. Biopsychosocial factors did not represent major obstacles in the lives of the hospice/bereavement volunteers. Though over half reported a family history suggesting vulnerability to illness and 64% had at least some concern about their current state of health, these concerns have not prevented them from serving as volunteers.

Psychological stressors were low with all reporting mood stability and 90% stating the employment of effective methods of self-care. Social stressors were also low with 90% reporting healthy relationships and 95% stating that they had a community of supportive friends.

About 93% of the participants reported spirituality as important in their lives and 90% believe in a Higher Power they identify as God.

Bereavement and mortality, two major components of hospice and bereavement work, both brought high scores among the participants, with 97% reporting the loss of loved ones and 95% a unique understanding of the loss(es) faced by their clients. 100% reported that they are comfortable with the fact that all living things die.

All participants reported that hospice/bereavement volunteerism is a rich experience and that they believe giving back is an important part of a life well-lived. All attempt to bring hope to their clients and believe that their own sufferings actually equip them to do so.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

From hospice and bereavement volunteers with more than 20 years of service, seven (7) narratives were collected with each one approximately one paragraph in length. Each handwritten document was typed verbatim and coded.

Participants were given a two-part question and provided time to answer it in their own words: “Have your own personal experiences influenced your desire to work in bereavement and why do you volunteer in this way?”

The first part of the question elicited a yes/no answer but all seven participants explained their responses. 100% of the participants reported that yes, their own personal experiences had influenced their desire to work in bereavement, and all seven reported that these experiences had involved death. Participants are listed as Volunteers A-G, respectively:

“My own personal experiences have had an influence on my desire to work with clients facing death or loss, and I appreciate the help that is and has been given to me”. (Volunteer A, 1 reference)

“Volunteering in the cancer center is very personally rewarding having gone through it myself”. (Volunteer B, 2 references)

“My dear father died suddenly and then my father-in-law died in hospice care… the pieces came together”. (Volunteer C, 5 references)

“I worked with homeless combat veterans from WWII and saw many die on skid row.

I used my time to minister to dying people over 24years”. (Volunteer D, 3 references)

“My mother died when I was 7, my dad when I was 16. My grandmother, aunt, dad and sister helped me with my grief. I’ve been through breast cancer myself”. (Volunteer E, 6 references)

“My dad died of colon cancer, and the Hospice Nurse went out of her way to be kind and understanding. I’ve had some medically unexplainable cures in my life fighting cancer”. (Volunteer F, 2 references)

“I made this decision when my mother received end-of-life hospice care and it was such a caring, positive experience”. (Volunteer G, 4 references)

In every case, experiencing loss had been a formative experience which, according to each volunteer, had been instrumental in his/her decision to become a hospice/bereavement volunteer. Of the seven respondents, three reported having gone through cancer themselves and believed this, too, had influenced the desire to volunteer in the field of hospice and bereavement.

In the second-cycle, focused coding was used to categorize these data and group them together in thematic clusters. Below are the categories, the number of responses in each category and examples of the concepts expressed:

• Profession: (6) Military Veteran, Nursing Home Administrator, Chaplain, Hospice Training, Nursing, Education

• Altruism: (15) Give back, support each other, pay it forward, passion towards helping others, listening to their voices, being there, reaching out, being with, grief is shared, make a difference, connect, bring healing

• Spirituality (13) Faith, felt called, cannot explain it (mystery), “Where I am meant to be”, Compassion comes from God, Chaplain, God many times places me, presentation at our church, sign, unexpected meeting (sign), spirituality

• Fulfilment (15) Appreciate help I’ve received, rewarding, fulfills me, sense of purpose, I gain, I learn, have received support, understand my own grief, FVHH is part of who I am, makes me a better person, received more than I have given, facilitating has enriched my life

Though some mentioned that their professional training and careers had played a part in their interest in hospice and bereavement work, there were only six references to this condition; in contrast, there were fifteen references to the beliefs about helping others, the importance of human connection and the value of bringing support to clients facing death and loss.

Among the seven participants, there were thirteen references to spirituality and faith; one participant identifying faith as the underlying reason for her desire to serve in this capacity. Two participants identified God as the source of their volunteerism with others mentioning spirituality in terms more abstract such as “feeling called” or “being placed in the right place at the right time”. In every case, spirituality was described as a reality beyond oneself.

Fifteen references were noted regarding the personal fulfillment experienced by the volunteers, ranging from the fact that hospice/bereavement work is experienced as deeply rewarding to the belief that it has been instrumental in identity formation. Four participants believed that they, after 20 years of service, have received far more than they have given, suggesting humility and gratitude. A single quote that captures well the collective sentiments of these seven participants: “I volunteer because it fulfills me and gives me a sense of purpose. I gain so much insight, meet so many wonderful people, hear so many incredible stories, learn so much about the human capacity for persevering and so much about love. All I have experienced in life has brought me to this place where I am meant to be”. (Volunteer C)

In conclusion, the seven narratives provided statements which denoted recurring themes of altruism (15 statements), fulfillment (15 statements) and spirituality (13 statements). The largest recurring theme, however, was that of mortality and bereavement (34 total references). The themes reflected in the volunteers’ stories confirm the quantitative date that the volunteers are comfortable with death and grief, that spirituality is important to them, that volunteering is personally fulfilling and that regardless of one’s personal suffering, altruism is always the preferred decision.

Participants were given a two-part question and provided time to answer it in their own words: “Have your own personal experiences influenced your desire to work in bereavement and why do you volunteer in this way?”

The first part of the question elicited a yes/no answer but all seven participants explained their responses. 100% of the participants reported that yes, their own personal experiences had influenced their desire to work in bereavement, and all seven reported that these experiences had involved death. Participants are listed as Volunteers A-G, respectively:

“My own personal experiences have had an influence on my desire to work with clients facing death or loss, and I appreciate the help that is and has been given to me”. (Volunteer A, 1 reference)

“Volunteering in the cancer center is very personally rewarding having gone through it myself”. (Volunteer B, 2 references)

“My dear father died suddenly and then my father-in-law died in hospice care… the pieces came together”. (Volunteer C, 5 references)

“I worked with homeless combat veterans from WWII and saw many die on skid row.

I used my time to minister to dying people over 24years”. (Volunteer D, 3 references)

“My mother died when I was 7, my dad when I was 16. My grandmother, aunt, dad and sister helped me with my grief. I’ve been through breast cancer myself”. (Volunteer E, 6 references)

“My dad died of colon cancer, and the Hospice Nurse went out of her way to be kind and understanding. I’ve had some medically unexplainable cures in my life fighting cancer”. (Volunteer F, 2 references)

“I made this decision when my mother received end-of-life hospice care and it was such a caring, positive experience”. (Volunteer G, 4 references)

In every case, experiencing loss had been a formative experience which, according to each volunteer, had been instrumental in his/her decision to become a hospice/bereavement volunteer. Of the seven respondents, three reported having gone through cancer themselves and believed this, too, had influenced the desire to volunteer in the field of hospice and bereavement.

In the second-cycle, focused coding was used to categorize these data and group them together in thematic clusters. Below are the categories, the number of responses in each category and examples of the concepts expressed:

• Profession: (6) Military Veteran, Nursing Home Administrator, Chaplain, Hospice Training, Nursing, Education

• Altruism: (15) Give back, support each other, pay it forward, passion towards helping others, listening to their voices, being there, reaching out, being with, grief is shared, make a difference, connect, bring healing

• Spirituality (13) Faith, felt called, cannot explain it (mystery), “Where I am meant to be”, Compassion comes from God, Chaplain, God many times places me, presentation at our church, sign, unexpected meeting (sign), spirituality

• Fulfilment (15) Appreciate help I’ve received, rewarding, fulfills me, sense of purpose, I gain, I learn, have received support, understand my own grief, FVHH is part of who I am, makes me a better person, received more than I have given, facilitating has enriched my life

Though some mentioned that their professional training and careers had played a part in their interest in hospice and bereavement work, there were only six references to this condition; in contrast, there were fifteen references to the beliefs about helping others, the importance of human connection and the value of bringing support to clients facing death and loss.

Among the seven participants, there were thirteen references to spirituality and faith; one participant identifying faith as the underlying reason for her desire to serve in this capacity. Two participants identified God as the source of their volunteerism with others mentioning spirituality in terms more abstract such as “feeling called” or “being placed in the right place at the right time”. In every case, spirituality was described as a reality beyond oneself.

Fifteen references were noted regarding the personal fulfillment experienced by the volunteers, ranging from the fact that hospice/bereavement work is experienced as deeply rewarding to the belief that it has been instrumental in identity formation. Four participants believed that they, after 20 years of service, have received far more than they have given, suggesting humility and gratitude. A single quote that captures well the collective sentiments of these seven participants: “I volunteer because it fulfills me and gives me a sense of purpose. I gain so much insight, meet so many wonderful people, hear so many incredible stories, learn so much about the human capacity for persevering and so much about love. All I have experienced in life has brought me to this place where I am meant to be”. (Volunteer C)

In conclusion, the seven narratives provided statements which denoted recurring themes of altruism (15 statements), fulfillment (15 statements) and spirituality (13 statements). The largest recurring theme, however, was that of mortality and bereavement (34 total references). The themes reflected in the volunteers’ stories confirm the quantitative date that the volunteers are comfortable with death and grief, that spirituality is important to them, that volunteering is personally fulfilling and that regardless of one’s personal suffering, altruism is always the preferred decision.

APPLICATIONS AND USES OF THE VAS

The VAS is not intended to rank or otherwise evaluate volunteers. Its purpose is for the volunteer to evaluate her/his attributes related to serving hospice clients. Such an activity in cooperation with hospice administration may assist each one to build a lasting contribution to serving hospice clients. Volunteering is difficult in such service and gaining an understanding of one’s motivation to do so is important to ascertain.

The varying ways that the VAS can be used include the following:

1. The VAS can be used as part of the initial screening of new volunteers. It can be especially helpful in helping persons new to hospice and volunteering to appraise their motives for service. Applicants can complete the VAS and discuss the result with administration. The VAS taps those qualities essential to successful service and provides the guide to discussions about becoming a volunteer.

2. The VAS can be used with volunteers who begin service with good intentions, but have been overwhelmed by their experiences. With administrative guidance they can ascertain those areas of concern using the VAS as a neutral means for supplying those issues of strength and those of concern.

3. The VAS can be used for in-service with current volunteers. Participants complete the instrument and an administrative leader can conduct adiscussion whereby the eight areas of assessment are addressed. The VAS can be a means of building a cohesive team of volunteers who understand their mission.

4. The VAS can be used for one or more volunteers whose service is lagging or detrimental to the agency’s standards. The topics raised by completing the VAS give such individuals a framework to understand their motivation for service and work effort. They are helpful to a supervisor by giving focus to what personal attributes are required.

5. The VAS, if used in different geographic areas, can help identify similarities and differences among volunteers in different states, and the unique needs experienced in rural and urban areas, thereby providing valuable information to funding sources.

The varying ways that the VAS can be used include the following:

1. The VAS can be used as part of the initial screening of new volunteers. It can be especially helpful in helping persons new to hospice and volunteering to appraise their motives for service. Applicants can complete the VAS and discuss the result with administration. The VAS taps those qualities essential to successful service and provides the guide to discussions about becoming a volunteer.

2. The VAS can be used with volunteers who begin service with good intentions, but have been overwhelmed by their experiences. With administrative guidance they can ascertain those areas of concern using the VAS as a neutral means for supplying those issues of strength and those of concern.

3. The VAS can be used for in-service with current volunteers. Participants complete the instrument and an administrative leader can conduct adiscussion whereby the eight areas of assessment are addressed. The VAS can be a means of building a cohesive team of volunteers who understand their mission.

4. The VAS can be used for one or more volunteers whose service is lagging or detrimental to the agency’s standards. The topics raised by completing the VAS give such individuals a framework to understand their motivation for service and work effort. They are helpful to a supervisor by giving focus to what personal attributes are required.

5. The VAS, if used in different geographic areas, can help identify similarities and differences among volunteers in different states, and the unique needs experienced in rural and urban areas, thereby providing valuable information to funding sources.

REFERENCES

- Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 196: 129-136.

- Wright B, Stone M (1979) Best test design. MESA Press, Chicago, USA.

- https://research.acer.edu.au/measurement/1/

- Wright B (1968) Sample-Free Test Calibration and Person Measurement. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

- Rasch G (1980) Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests Danmarks Paedagogiske Institut, København, Denmark.

Citation: Happ M, Stone M (2019) Volunteer Assessment Scale (VAS) for Assessing Hospice Workers. J Hosp Palliat Med Care 2: 007.

Copyright: © 2019 Marissa Happ, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!