Women in the United States Deserve Opioid Drug Policies that Improve Not Harm their Health Outcomes

*Corresponding Author(s):

Jonathan JK StoltmanOpioid Policy Institute, Little Rock, United States

Tel:+1 2488605374,

Email:jonathan.stoltman@opioidpolicy.org / jonathan.stoltman@gmail.com

Abstract

This article explores the impact of the current drug policy on women in the US and ways to move drug policy forward in a gender-responsive way. It examines the two competing, incompatible perspectives on addiction: “health” or “moral weakness”. Due to a historical policy alignment with the “moral weakness” perspective, the current drug policies adversely affect a woman’s ability to receive evidence-based care and parent their children. This article will review drug policies that focus on demand reduction, supply reduction and health improvement. Demand reduction approaches encompass law enforcement, drug courts, biological matrices for drug testing, and medication for opioid use disorder. The supply reduction section focuses on prescription data monitoring programs and continuing education. The health improvement section examines gaps in treatment and need to address both the medical and psychosocial concerns patients may have. This multifaceted approach to drug policy has aspects that yield multilayered adverse effects on women. Suggestions to address the shortcomings are identified including a Bill of Rights for women with opioid use disorder.

Keywords

Women; Substance use disorders; Incarceration; Pregnancy; Post-partum; Opioids

“HEALTH” OR “MORAL WEAKNESS” PERSPECTIVES DRIVE DRUG POLICY

Approximately 4.9 million women in the US have misused opioids in the past year [1]. The current opioid crisis is associated with increased morbidity [2] and mortality [3], across the US. Opioid agonists (e.g., oxycodone, heroin) provide pain relief and/or euphoria. Opioids can also serve as treatment medications for OUD by reducing cravings and withdrawal (MOUD; e.g., methadone, buprenorphine). All opioid agonists have both therapeutic potential and the potential for misuse. Accordingly, their legal status varies across countries where they are used. Where opioid misuse occurs, drug policies regulating opioid misuse follow.

This policy analysis focuses on the limits of current drug polices in the US and ways to move forward in a gender-responsive way. In the US, drug policy is driven by two competing perspectives on addiction: “health” or “moral weakness”. The World Health Organization and the National Institute on Drug Abuse both share the “health” perspective. Generally the “health” perspective regards addiction “as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences” [4]. Thus, the “health” perspective approaches problems with opioid use by connecting the individual with services and treatment through the medical and/or social services systems. In contrast, criminal justice bodies (e.g., law enforcement and the courts) generally favor the “moral weakness” perspective. Consequently, the “moral weakness” perspective relies on various criminal justice approaches (e.g., incarceration, drug raids) to reduce drug use and drug use associated harms [5].

The scale of the morbidity and mortality issues associated with the current opioid crisis have led to partnerships between “health” and “moral weakness” stakeholders. Yet, the “moral perspective, a foundation of most US drug policy, is in direct conflict with the goals of the “health” perspective. While this partnership can help “moral weakness” stakeholders learn about evidence-based “health” perspective policy approaches (e.g., providing MOUD for pregnant women), drug policy can be slow to react to an emerging drug crisis. Delays in policy response are due to electoral and timing issues, tension between data-driven and value-driven polices (e.g., “moral weakness” perspective is synonymous with the value of “being tough on crime”) and balancing the various stakeholder beliefs [6]. Therefore, the policies addressing drug use are often in response to previous drug crises [7]. Both our understanding of addiction as a treatable brain disease [8] and the nature of the current opioid crisis have made the harms associated with “moral weakness” policies more apparent.

The enactment and enforcement of drug policies occur at the local, national and international level and can impact both “moral weakness” law enforcement and “health” medical approaches [9]. A review of 107 drug policy interventions found scant effectiveness data for many drug policies [9] and even fewer policies have data associated with gender. Therefore, the present policy analysis focuses on the most pressing issues identified within the 107 drug policy interventions. Likewise, there is limited research on the impacts of opioid drug policy on the full spectrum of gender orientations (i.e., LGTBQIA+), although the negative effects of certain drug policies are apparent across the full spectrum of gender orientations [10,11]. Due to this limitation in the existing literature, this review will be restricted to a binary discussion of women (versus men) when considering opioid drug policy impacts.

Gender gaps in modern drug policy

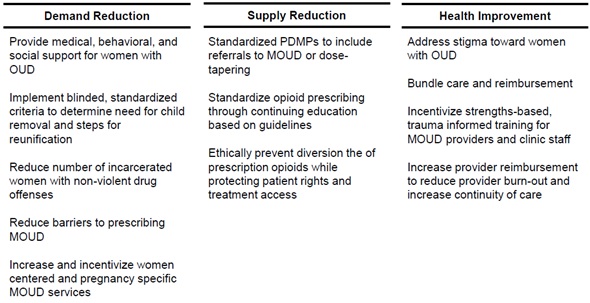

To date, many of the 107 drug policies do not incorporate gender-specific elements [9]. However, efforts are addressing this policy blind spot. In 2016, for the first time, the United Nations International Narcotics Control Board incorporated gender perspectives in the development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of drug policies and programs [12], but there is still a lack of gender-specific data. With this limitation in mind, we will review policy using the organizing framework of demand reduction, supply reduction and health improvement. Lastly, we will offer suggestions to address the shortcomings we have identified (Figure 1) and propose a Bill of Rights for women with OUD (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Policy solutions addressing gender inequities associated with current opioid policies.

Figure 1: Policy solutions addressing gender inequities associated with current opioid policies.

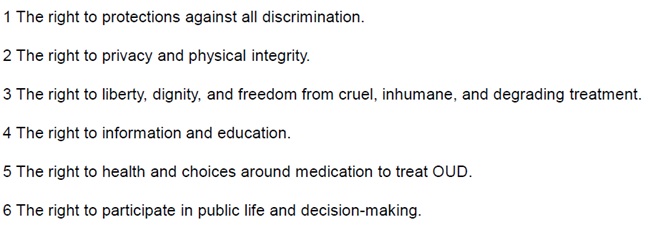

Figure 2: Bill of rights for women with opioid use disorder.

Figure 2: Bill of rights for women with opioid use disorder.

DEMAND REDUCTION

Demand reduction opioid drug policies can range from law enforcement approaches to evidence-based treatment and recovery services. When considered through a gendered lens, the law enforcement approach to demand reduction is generally the most problematic. Historically, law enforcement approaches lack an evidence base to support them and have frequently had disproportionately negative effects on women.

Law enforcement

Women are the fastest growing proportion of the American prison population with a 750% increase in incarcerated women from 1980 to 2017 [13]. The population of women in state prison for drug offenses increased from 12% in 1986 to 25% in 2017 [13]. In contrast, men in prison for drug offenses make up 14% of the prison population in 2017 [13]. Greater than 60% of women in federal prison are incarcerated for nonviolent drug related crimes [12,14]. A limitation of a criminal justice approach is the historical lack of distinction between those who sell drugs and those who use drugs. Conspiracy charges provide a specific example of why women are more likely to be imprisoned for drug offenses. Conspiracy charges may be brought against women who do not cooperate with a criminal investigation and live with or are family members with someone involved in the sale or distribution of drugs. Even more problematic, conspiracy charges have lengthy mandatory minimum sentencing even though the individual may have never been directly involved in drug sale or distribution.

Additionally, OUD in women is associated with Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) victimization [15]. The relationship between IPV and substance use is complex [16]. Some women may use opioids to numb emotions and physical pains while such use may also contribute to relationship stress (i.e., cost of drugs, access to drug; Smith et al. [15]). Abusive partners may manipulate a woman’s drug access in order to control her. Additionally, opioid use may cause side effects (e.g., cognition changes mental confusion and drowsiness) impairing women’s ability to detect or defend themselves in an unsafe environment [17]. Fear of law enforcement due to their own illegal drug use can contribute to women not seeking legal action against the perpetrator of this violence.

Drug courts

Drug courts are community level diversion programs bridging between prison and treatment for non-violent drug offenses. Because they exist at a community level, significant variations exist [18]. For example, some rely on detoxification instead of using the UN designated gold standard MOUD (i.e., methadone, buprenorphine, or oral morphine). A survey found that only half of drug courts allow for MOUD [19]. In some instances, testing positive for a MOUD can be a violation of the drug courts rules and lead to incarceration. In many jurisdictions, fetal rights supersede pregnant women’s rights. Therefore, pregnant women in drug court may be particularly at the mercy of systems that may force detoxification from opioids, including MOUD, a process that goes against medical guidance [20]. For incarcerated pregnant women, MOUD can be scarce. In the US, 67% of jails and 82% prisons provided MOUD for pregnant women [21]. In contrast, 17% or jails and 18% of prisons provided MOUD for non-pregnant women [21]. A lack of MOUD in prison increases the risk of overdose after release from prison [22].

Over reliance on biological matrices for drug testing

Women who use opioids are uniquely vulnerable to the criminal justice system due to risk of involvement with child welfare services. There are multiple avenues from which their opioid use might be accurately or falsely “discovered” by law enforcement through biological drug testing paradigms. For example, the mother may be tested for opioid use during pregnancy, or her infant may be tested for opioids at birth. Drug testing has been touted as a deterrent for harmful drug use in pregnancy. However, harms can also occur when non-confirmed testing yields false positive results. For example, from 2005 and 2015, a laboratory tested the hair of more than 16,000 individuals for drug consumption. Testing results were evidence in court and resulted in both temporary and permanent loss of custody of children. Only later was it discovered that the hair testing results were unreliable [23]. Urine drug screens also have potential unintended consequences such as driving women to avoid medical care to avoid mandatory reporting [24].

Positive drug toxicology tests can initiate the termination of parental rights, strip the mother of her choice to breastfeed and may lead to a denial of medical benefits. However, a positive drug screen is not sufficient to diagnose OUD, only patient self-report through verbal screening and clinical assessment can establish this. Nor does it representative of a women’s ability to parent. In practice, drug toxicology is often discriminatory (i.e., targeted testing of “suspicious women”) and the punitive policies that often result from a positive toxicological result are rarely grounded in science. For these reasons, the expert guidance from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology calls for the use of consented validated verbal universal drug screening in conjunction with referral to treatment to avoid discriminatory targeting [25], but this is not widely implemented.

Counter intuitively, harms associated with illicit drugs are often exaggerated and harms associated with licit drug use are minimized, although the rates of licit drug (i.e., alcohol, tobacco) use during pregnancy are higher and can have severe outcomes for the fetus and infant [26]. The consequences from drug testing during pregnancy can be widespread and radiate beyond the initial intention. These unintended consequences of testing for drug use during pregnancy include women avoiding prenatal care and drug treatment to avoid testing positive. Prenatal care is especially important during pregnancies where the mother uses drugs because prenatal care can often ameliorate the effects of drug use in pregnancy [27].

MOUD

MOUD (i.e., buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, naltrexone) is the gold standard for treating OUD as it provides relief from opioid craving and withdrawal through their long-acting binding to the opioid receptors. MOUD falls into both the demand reduction and health improvement policy categories. Outside of the basic pharmacological treatments and sometimes even these are denied to women, specific treatment needs that women may have (e.g., childcare, history of IPV) are often not met because there is rarely a holistic or family-centered approach to care for OUD.

MOUD is highly regulated at both the federal and state level and access is inconsistent across the US [28]. For example, outpatient methadone can only be administered by federally certified Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs). Buprenorphine requires prescribers to obtain additional training and a waiver from the FDA. Medicaid or private health plans may not always cover all MOUD forms and treatment medications may need prior authorization before initiating treatment. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) does not require insurance plans offer coverage for OUD in general, nor does it require coverage for evidence-based treatments. These issues, coupled with inadequate reimbursement rates for service, yield few treatment providers available. With limits on providers and coverage, this adds to the substantial barriers that women must overcome to receive MOUD. There is also limited access to MOUD for those living in poverty, those in rural areas, those who are uninsured, or are insured through Medicaid.

Pregnancy focused MOUD: The rate of OUD diagnoses among women during labor and delivery has more than quadrupled over a 15-year period ending in 2014 [29]. Concomitantly, the number of states with one or more policies on drug use during pregnancy has steadily increased since 1970 with an increase in punitive policies over time [30]. Such punitive polices have become more prevalent despite the lack of evidence supporting the idea that punitive responses decrease drug use during pregnancy. The primary shortcoming of punitive policies is their failure to recognize or ameliorate the inadequacies in the healthcare system and other supportive services for pregnant women who use drugs.

For example, federal dosing regulations have harmed pregnant women and their fetuses because they do not account for the metabolic changes that accompany pregnancy [31]. In addition to harmful dosing regulations, other punitive policies are associated with increased rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome [32]. Many MOUD facilities do not have specialized services for pregnant women and most MOUD programs are ill-equipped to handle the unique challenges women may face after delivery. For example, only 15% of treatment centers offer specified services for pregnant women [33] and the quality of treatment can range dramatically. While standard of care for pregnant women with an OUD is MOUD, detoxification during pregnancy still occurs at a doctor’s or court order. Pressure can come from providers to “detox” in pregnancy purportedly to reduce neonatal abstinence syndrome. However, this approach is unethical due to the lack of evidence supporting “detox” in pregnancy and the salient risks present for both the mother and infant. The refusal to provide MOUD during pregnancy is unethical and ineffective under any circumstance [20]. Additionally, some obstetricians and gynecologists will not accept pregnant patients on MOUD and many treatment programs refuse to provide MOUD to pregnant women. A growing number of states are working to make treatment more readily available to pregnant women, however progress is uneven nationally.

The 4th Trimester (delivery up to the 1st year post-pregnancy), is a growing research focal area but policies are lagging [34]. The 4th Trimester is a window where many women and infants fall into the gaps inherent to the transitions from the regular and frequent appointments with the prenatal care provider to pediatrician. Care of the mother shifts from a medical focus to a discontinuation in Medicaid coverage at 6 weeks post-partum. Loss of health insurance coverage can lead to loss of treatment for substance use disorders and mental health care as well as lack of care for other physical health issues. This is particularly true for women with severe maternal morbidity at the time of delivery [35]. Lack of access to care in the first year after delivery also increases the risk of maternal mortality secondary to suicide, overdose and untreated medical issues [36].

Demand reduction policy solutions

Drug testing and law enforcement policy solutions: Changing our law enforcement approach can contribute to greater family stability and better health outcomes. Sixty percent of women in prison are mothers of minor children [37]. Substance misuse, trauma and mental health are often interrelated among women in prison [38]. Rather than punishing women with OUD, which may exacerbate the problem and further marginalize a disenfranchised population, future policies should address the needs of women in treatment by integrating the medical, behavioral and social service for the women and their families [26].

The health and social situations of mothers involved with child protective services often deteriorate after their child is taken into state custody. Research shows that both informal and official custody loss predicts increased drug use among women [39,40]. Removing a parent is destabilizing to the family unit [41] and women with foster care involvement are less likely to complete treatment than non-affected peers [14]. This loss of family stability is difficult to reestablish post-incarceration because the women are unable to obtain public assistance (e.g., food assistance, educational assistance), can have difficulty securing jobs and housing and are often ineligible for OUD treatment programs as dictated by probation/parole [42]. Mothers can benefit from establishment of support to assist with the negative outcomes they have experienced after the loss of their child to state custody) [43]. Such support helps mothers immediately and can reduce future barriers to reunification. A straightforward way to avoid these issues is to prohibit drug testing that acts under the auspices of health care while in reality is used to target “suspicious women”. If biological matrices are to be tested for drugs, such testing must be universally applied with true informed consent and any positive results must be confirmed with GC/MS followed by earnest help and support, not shame and punitive responses. In the event of child protective services involvement, there should be blinded, standardized and unambiguous criteria to determine need for child removal and steps for reunification.

Future policy related to demand reduction must address the current non-violent drug-offending prison population and develop new approaches to reduce future non-violent drug-offending imprisonment. First, steps should be taken to evaluate which women currently incarcerated for non-violent drug offenses may be able to be released from prison [44]. Second, women who have specifically been incarcerated for opioid-related charges should be provided MOUD while incarcerated and upon release in conjunction with post-prison rehabilitation service, something currently lacking [5,45]. This lack of evidence-based care in prison (e.g., forcible withdrawal, lack of MOUD) can adversely impact treatment seeking behaviors upon release [46]. Additionally, incarcerated women should no longer be denied medical care such as an abortion, perinatal care and access to reproductive/sexual health services [47,48]. Women should not lose Medicaid due to incarceration. Such gaps lead to an inability to receive services once outside walls of incarceration. The ban on the shackling of pregnant women should expand from the federal level in the U.S. [49], to state prisons and county jails. Lastly, incarcerated women need services that are equal or greater than those for men (e.g., informal leadership positions among those incarcerated and prevention of gender-based violence; Swavola et al. [41]).

The current policy of criminalization of opioid use puts the mother and fetus at great risk due to the barriers to treatment and prenatal care that a positive test can entail [41].

MOUD policy solutions: There are several policy changes that can both increase access to MOUD and increase the level of care offered at MOUD facilities. First, reducing barriers to prescribing MOUDs. Currently, buprenorphine prescribing is limited by an DEA X waiver, but recent calls have pushed for deregulating this life-saving treatment medication [50]. Deregulating buprenorphine could quickly expand access to MOUD. For methadone, federal regulations need updating to allow perinatal women to receive multiple daily doses of methadone to optimize mother-child outcomes.

Second, to increase the quality of care at MOUD facilities, governments can prioritize and incentivize easily accessible, evidence-based health care for women with OUD. This can happen two ways: 1) more MOUD facilities should integrate other healthcare offerings; and 2) more primary care providers should expand their practice to include MOUD. These new arrangements to offer integrated care can serve as a bridge to other health care offerings (e.g., pediatrics, infectious disease specialists) and may promote uptake of these services by patients with OUD. An integrated approach to MOUD facilities can benefit all women in treatment, especially women in rural settings. The addition of OUD telehealth options for care could further expand access in areas with limited healthcare resources and for women facing additional barriers to care such as transportation and childcare [51]. The inclusion of these additional medical specialties can help patients reach the goal of whole body and mind health for the family.

Third, safe environments for women should be created within each MOUD facility. Governments and accreditation groups can create incentives for MOUD facilities to develop and enforce rules that guarantee the personal safety and confidentiality of all patients. To provide a safe environment, MOUD facilities should include gender-specific, trauma responsive groups. Women are especially vulnerable in clinics without this additional structure due to the high rates of trauma experienced by women in this population and the possibility that their partner and/or abuser may also be in the same treatment facility. To guarantee the personal safety and confidentiality of women in treatment, facilities should consider having women-only spaces. If women-only spaces are not feasible, women-only times should be implemented. These dedicated spaces or times for women are particularly important in facilities that have women who were or are engaged in sex work or women who have experienced violence.

Pregnancy focused MOUD policy solutions: Integrated programs that target both behavioral and non-behavioral health needs of pregnant women with OUD should include parenting classes and other child-focused services. Childcare is often not provided at treatment facilities due to structural and regulatory challenges. Future policies can address this gap in childcare services by creating incentives to offer these programs and pathways to work with state-level departments of education to allow for these arrangements at facilities that meet certain requirements. Sterile, private and accessible breast-feeding solutions are also needed in MOUD facilities. Lastly, to address capacity shortages in obstetrics/gynecologists and MOUD providers, a combination of incentives and increased insurance coverage should be used.

SUPPLY REDUCTION

While most drug policies are demand reduction oriented, supply reduction continues to be an important approach. The economics of supply theory underpins supply reduction efforts that focus on crop eradication, legal prohibition and enforcement of transit restrictions to reduce drug supply [52,53]. This discussion focuses only on one aspect of supply reduction efforts.

Prescription data monitoring programs

Prescription Data Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) are intended to decrease the morbidity and mortality related to opioids and other drugs with abuse potential. Evaluating PDMPs is a challenge because they vary in their implementation at the state level. They can be tailored to monitor the patient and/or the doctor’s behavior to decrease prescription diversion. PDMPs can operate by notifying prescribers of a patients engaging in “doctor shopping” behavior and/or reduce over prescribing practices of these drugs through monitoring of controlled substance prescriptions [54]. While PDMPs are widespread, there is little evidence that demonstrates PDMPs effectively achieve their intended goals of decreasing the morbidity and mortality related to opioids [54]. This may be due to gaps in MOUD. For example, reducing pharmaceutical access without increasing treatment access may have exacerbated the current heroin and synthetic opioid analogue overdose crisis [55]. In the course of 20 years, the current opioid crisis has shifted from primarily prescription opioid misuse (wave 1) to heroin use (wave 2) to synthetic opioid analogues (wave 3; i.e., fentanyl) potentially limiting the role of PDMPs.

Supply reduction policy solutions

To maximize PDMPs as an opioid policy tool, best practices should be incentivized across states. The current best practices are to include a referral to MOUD or dose tapering, when individuals are cut-off from their supply of prescription opioids [44], but this has not yet been widely adopted. Further research is needed to evaluate whether the current implementation of PDMPs, often without referral to MOUD, disproportionately affect women.

Recommendations for standardizing prescribing practices has been identified as an additional solution and was recently tasked to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine by the FDA [56]. The CDC published their updated guidelines for prescribing of opioids for chronic pain which prompted mandatory continuing education for opioid prescribing practices for all prescribers and trainees [57]. Regulation and enforcement of these standards occurs at the state licensure level and by the DEA. Preventing the diversion of medication for non-medical purposes remains an important shared goal of the international community; however, this should not occur in a manner that reduces the availability of and access to controlled substances for medical and scientific purposes, such as MOUD. A concerted international approach is needed to stop extrajudicial acts of violence or reprisal against persons suspected of illicit drug-related activity. Such government-sponsored violence against individuals associated with drug-related activity is alarming and counter to the scientific consensus of addiction as a medical disease in need of science-based treatment.

HEALTH IMPROVEMENT

As stated previously, MOUD falls under both the demand reduction policy category as well as the health improvement policy category. Women with OUD tend to experience a greater variety of life challenges compared to men with OUD [58-60]. As such, women need treatment that addresses medical, psychosocial and internalized issues. Access to treatment is a global issue for women, almost all countries need to expand women-responsive treatment if they are to achieve the highest attainable standard of health for women [12]. For example, residential treatment programs often do not admit women with children [12]. While women make up 1/3 of individuals who use drugs, just 1/5 of those who are treated. Structural level issues include a lack of childcare services and women-specific programming as well as judgmental attitudes towards women who use drugs, especially during pregnancy.

Health improvement policy solutions

Due to the prevailing stigma and discrimination surrounding OUD, many communities gravitate towards criminal justice approaches rather than treatment approaches. Part of this stigma has been fueled from disparate access to substance use treatment. Historically, primary access to treatment was rendered by paying for services out of pocket. A potential policy solution would be for flexibility around federal and state funding, expansion of substance use services covered through both public and private insurance, as well as service bundling reimbursement of services in a capitated not fee for service model. A capitated model has compensation based on the expected care the patient will receive; therefore, greater payments are received for more complex patients.

Well-designed opioid policies can improve treatment facilities and treatment providers skills to positively impact women’s health. Additional training is needed to educate current and future addiction treatment providers on strengths-based, trauma informed approaches for women with OUD [12]. Incentives and certifications can encourage providers to seek this additional training so that facilities can function optimally. Additionally, policies should provide adequate reimbursement for services so that addiction treatment providers are able to address multiple treatment access gaps and have a living wage.

Appropriate reimbursement can reduce treatment provider burn-out and contribute to better continuity of care. Current policies exist in the US to provide loan forgiveness for addiction treatment providers in under-served, high-need areas [61]. The current loan forgiveness program can be used as a model to provide incentives for providing women-specific services .

CONCLUSION

Punitive opioid polices founded upon a “moral weakness” perspective harms women in radiating ways. Therefore, any new policies should be built upon an evidence-based framework and respect for individuals with an OUD. This practice has been used to guide the development and enactment of laws, policies and practices that address the HIV crisis in the US [62,63] and can be adapted for the opioid crisis (Figure 2).

The right to protections against all discrimination.

This includes protections when seeking health care coverage for MOUD and recovery or related services. To be a non-discriminatory policy, it must not have a disproportionate impact on people living with OUD or codify stigmatizing and discriminatory treatment (e.g., the practices cited above that deny MOUD to pregnant women).

The right to privacy and physical integrity

This includes protections against mandatory, or coercive testing. Confidentiality related to testing and disclosure of opioid use or OUD should be maintained. The right to physical integrity also covers the ability to decide when and whether to have a child.

The right to liberty, dignity and freedom from cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment

This includes protection from incarceration for non-violent drug offenses, segregation, or isolation in a special hospital or prison ward. The right to freedom from violence includes sexual violence, abuse, harassment, mandatory testing, or OUD-based incarceration.

The right to information and education

This includes the right to have access to comprehensive information about OUD prevention, treatment and recovery. This right covers reproductive/sexual health services that are accurate, comprehensive, accessible and culturally appropriate. This information is required to make a voluntary, informed decisions.

The right to health and choices around medication to treat OUD

This includes the right to evidence-based, available, accessible, acceptable and quality health care. This right prevents the denial of access to the highest quality health care or treatment on the basis of OUD. The UN has designated buprenorphine, methadone and oral morphine as the gold standard of treatments for OUD. Denial of these lifesaving medications in the absence of evidence supporting its denial is a violation of this right. Denial of MOUD for pregnant women is a violation of this right.

The right to participate in public life and decision-making

This includes the right of OUD-affected communities and individuals to participate in the formulation and implementation of evidence-based OUD policy at every level. Meaningful participation is necessary, “decide nothing about us, without us.”

Current opioid drug policies disproportionately affect women and are often in conflict with “health” perspectives. By using an evidence-based, gendered lens to focus future policies, we can better achieve outcomes for the public good such as reducing initiation of drug use, reducing drug-use consequences, reducing the supply of illicit drugs and reducing the supply of diverted prescription drugs used for non-medical purposes.

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization JJKS, HJ; Supervision HJ; Visualization JJKS; Roles/Writing-original draft JJKS, HJ; Writing - review & editing JJKS, ASM, MR, EJ, HJ, LL.

REFERENCES

- NSDUH (2019) The National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2017. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Ronan MV, Herzig SJ (2016) Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections from 2002 to 2012. Health Aff (Millwood) 35: 832-837.

- Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM (2016) Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths--United States, 2000-2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64: 1378-1382.

- NIDA (2018) Drugs, brains and behavior: The science of addiction.

- Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND (2009) Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: Improving public health and safety. JAMA 301: 183-190.

- Midgley G, Winstanley A, Gregory W, Foote J (2005) Monograph No. 13: Scoping the potential uses of systems thinking in developing policy on illicit drugs. DPMP Monograph Series.

- Reuter P (2013) Why has US drug policy changed so little over 30 years? Crime and Justice 42: 75-140.

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (2016) Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med 374: 363-371.

- Ritter A, McDonald D (2005) Monograph No. 02: Drug policy interventions: A comprehensive list and review of classification schemes. DPMP Monograph Series.

- Collins AB, Bardwell G, McNeil R, Boyd J (2019) Gender and the overdose crisis in North America: Moving past gender-neutral approaches in the public health response. Int J Drug Policy 69: 43-45.

- Oberheim TS, DePue KM, Hagedorn BW (2017) Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) in transgender communities: The need for trans?competent SUD counselors and facilities. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling 38: 33-47.

- International Narcotics Control Board (2017) Chapter 1. Women and Drugs. In Report 2016: UN.

- The Sentencing Project (2019) Incarcerated Women and Girls.

- Drug Policy Alliance (2018) Women, Prison and the Drug War.

- Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR (2012) Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Addict Behav 10:1037/0024855.

- Stone R, Rothman EF (2019) Opioid use and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Current Epidemiology Reports 6: 215-230.

- Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, Buenaventura R, Adlaka R, et al. (2008) Opioid complications and side effects. Pain physician 11: 105-120.

- Rossman SB, Roman JK, Zweig JM, Rempel M, Lindquist CH (2011) The multi-site adult drug court evaluation: The impact of drug courts.

- Matusow H, Dickman SL, Rich JD, Fong C, Dumont DM, et al. (2013) Medication assisted treatment in US drug courts: Results from a nationwide survey of availability, barriers and attitudes. J Subst Abuse Treat 44: 473-480.

- ACOG Committee on Ethics (2016) Committee Opinion No. 664: Refusal of medically recommended treatment during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 127: 175-182.

- Sufrin C, Sutherland L, Beal L, Terplan M, Latkin C, et al. (2020) Opioid use disorder incidence and treatment among incarcerated pregnant women in the United States: Results from a national surveillance study. Addiction.

- Ranapurwala SI, Shanahan ME, Alexandridis AA, Proescholdbell SK, Naumann RB, et al. (2018) Opioid overdose mortality among former North Carolina inmates: 2000-2015. Am J Public Health 108: 1207-1213.

- Boyd S (2019) Gendered drug policy: Motherisk and the regulation of mothering in Canada. International Journal of Drug Policy 68: 109-116.

- Stone R (2015) Pregnant women and substance use: Fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health & Justice 3.

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice (2017) Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 130: 488-489.

- Terplan M, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Chisolm MS (2015) Prenatal substance use: Exploring assumptions of maternal unfitness. Subst Abuse 9: 1-4.

- Finnegan LP (1978) Management of pregnant drug-dependent women. Ann N Y Acad Sci 311: 135-146.

- Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E (2015) National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health 105: 55-63.

- Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM (2018) Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization-United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67: 845-849.

- Thomas S, Treffers R, Berglas NF, Drabble L, Roberts SCM (2018) Drug use during pregnancy policies in the United States from 1970 to 2016. Contemporary Drug Problems 45: 441-459.

- McCarthy JJ, Graas J, Leamon MH, Ward C, Vasti EJ, et al. (2020) The use of the methadone/metabolite ratio (MMR) to identify an individual metabolic phenotype and assess risks of poor response and adverse effects: Towards scientific methadone dosing. J Addict Med.

- Faherty LJ, Kranz AM, Russell-Fritch J, Patrick SW, Cantor J, et al. (2019) Association of punitive and reporting state policies related to substance use in pregnancy with rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome. JAMA Netw Open 2: 1914078.

- Terplan M, Longinaker N, Appel L (2015) Women-centered drug treatment services and need in the United States, 2002-2009. Am J Public Health 105: 50-54.

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice (2018) ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol 132: 784-785.

- Gordon SH, Sommers BD, Wilson IB, Trivedi AN (2020) Effects of medicaid expansion on postpartum coverage and outpatient utilization. Health affairs 39: 77-84.

- Goldman-Mellor S, Margerison CE (2019) Maternal drug-related death and suicide are leading causes of postpartum death in California. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 221: 481-489.

- Lewandowski CA, Hill TJ (2008) The impact of foster care and temporary assistance for needy families (TANF) on women's drug treatment outcomes. Child Youth Serv Rev 30: 942-954.

- Covington SS, Bloom BE (2007) Gender responsive treatment and services in correctional settings. Women & Therapy 29: 9-33.

- Harp KLH, Oser CB (2018) A longitudinal analysis of the impact of child custody loss on drug use and crime among a sample of African American mothers. Child Abuse Negl 77: 1-12.

- Kenny KS, Barrington C, Green SL (2015) "I felt for a long time like everything beautiful in me had been taken out": Women's suffering, remembering, and survival following the loss of child custody. Int J Drug Policy 26: 1158-1166.

- Swavola E, Riley K, Subramanian R (2016) Overlooked: Women and jails in an era of reform. Vera Institute of Justice, New York, USA.

- Kozhimannil KB, Graves AJ, Levy R, Patrick SW (2017) Nonmedical use of prescription opioids among pregnant US women. Womens Health Issues 27: 308-315.

- Killeen T, Brady KT (2000) Parental stress and child behavioral outcomes following substance abuse residential treatment. Follow-up at 6 and 12 months. J Subst Abuse Treat 19: 23-29.

- Global Commission on Drug Policy (2017) The opioid crisis in North America. Global Commission on Drug Policy, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Winkelman TN, Ford BR, Shlafer RJ, McWilliams A, Admon LK, et al. (2020) Medications for opioid use disorder among pregnant women referred by criminal justice agencies before and after Medicaid expansion: A retrospective study of admissions to treatment centers in the United States. PLOS Med 17: 1003119.

- Grella CE, Ostile E, Scott CK, Dennis M, Carnavale J (2020) A scoping review of barriers and facilitators to implementation of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder within the criminal justice system. International Journal of Drug Policy 81: 102768.

- ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women (2011) Health care for pregnant and postpartum incarcerated women and adolescent females. Obstetrics & Gynecology 118: 1198-1202.

- Sufrin C, Kolbi-Molinas A, Roth R (2015) Reproductive justice, health disparities and incarcerated women in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 47: 213-219.

- First Step Act U.S.C. (2018).

- Fiscella K, Wakeman SE, Beletsky L (2019) Buprenorphine deregulation and mainstreaming treatment for opioid use disorder: X the X Waiver. JAMA Psychiatry 76: 229-230.

- Guille C, Simpson AN, Douglas E, Boyars L, Cristaldi K, et al. (2020) Treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnant women via telemedicine: A nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Netw Open 3: 1920177.

- Reuter P, Kleiman MAR (1986) Risks and prices: An economic analysis of drug enforcement. Crime and Justice 7: 289-340.

- Wisotsky S (1983) Exposing the war on cocaine: The futility and destructiveness of prohibition. Wisconsin Law Review 6: 1305-1426.

- Islam MM, McRae IS (2014) An inevitable wave of prescription drug monitoring programs in the context of prescription opioids: Pros, cons and tensions. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 15: 46.

- Cicero TJ (2018) Is a reduction in access to prescription opioids the cure for the current opioid crisis? Am J Public Health 108: 1322-1323.

- National Academies of Sciences (2020) In Framing Opioid Prescribing Guidelines for Acute Pain: Developing the Evidence. National Academies Press, Washington DC, USA.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R (2016) CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. Journal of the American Medical Association 315: 1624-1645.

- Back SE, Payne RL, Wahlquist AH, Carter RE, Stroud Z, et al. (2011) Comparative profiles of men and women with opioid dependence: Results from a national multisite effectiveness trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 37: 313-323.

- Luthar SS, Gushing G, Rounsaville BJ (1996) Gender differences among opioid abusers: Pathways to disorder and profiles of psychopathology. Drug Alcohol Depend 43: 179-189.

- Stenbacka M, Beck O, Leifman A, Romelsjö A, Helander A (2007) Problem drinking in relation to treatment outcome among opiate addicts in methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Rev 26: 55-63.

- HRSA (2018) NHSC Substance Use Disorder Workforce Loan Repayment Program.

- Fried ST, Kelly B (2011) Gender, race + geography = jeopardy: Marginalized women, human rights and HIV in the United States. Womens Health Issues 21: 243-249.

- OHCHR, UNAIDS (2007) Handbook on HIV and Human Rights for National Human Rights Institutions. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Geneva, Switzerland.

Citation: Stoltman JJK, Momand AS, Ramage M, Lander LR, Johnson E, et al. (2020) Women in the United States Deserve Opioid Drug Policies that Improve Not Harm their Health Outcomes. J Addict Addictv Disord 7: 48.

Copyright: © 2020 Jonathan JK Stoltman, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.