Changes in Dietary Behavior of Arab International Students in the US

*Corresponding Author(s):

Abdulaziz Kh Al-FarhanNutrition And Dietetics, The Public Authority For Applied Education And Training, School Of Health Science, College Of Nursing, Kent State University, Ohio, United States

Tel:+1 5174888661,

Email:alfarha4@msu.edu, nutraziz@gmail.com

Abstract

Methods

Results

Conclusion

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Annually, the United States (US) hosts up to 1.1 million international students from around the world [1]. The majority of international students experience significant cultural transitions and challenges [2], such as establishing undesirable eating and lifestyle habits [3], experience weight change, diet, and eating pattern [4], which may also vary by genders and/or marital status [5]. International students often face a cultural shock that may cause compulsive eating and drinking as a result of social isolation and depression [6]. As a result, they may have a hard time maintaining their typical eating habits due to limited access or availability of their own typical or traditional (cultural) food and lack of food preparation and cooking skills [7]. Cultures around the world are influenced by Westernized food [8], particularly in the form of fast food [9], which is linked to changing dietary habits, increased consumption of foods high in fat and/or refined sugars, and increasing prevalence of obesity [10]. There is possibly an increase of substituting certain cultural food choices and food practices preferred by international students after relocating to the US due to cultural food scarcity and/or poor cooking and food preparation skills [3]. An important point to clarify is that some non-Westernized (traditional) foods are not necessary nutrient-dense due to their high content of fat (steric and palmitic saturated fat), cholesterol, and sodium [11]. Some literature defined Westernized fast food as foods that are purchased, not cooked at home, self-service or carry out [12], other described that westernized diet includes French fries, potato chips, and cakes [13]. This study refers to traditional (cultural), food way of specific ethnic group, cooked and/or self-prepared at home, and encourages consuming a balanced diet from food groups [14]. Arab college students consume varied mixed diets including traditional and westernized food choices [15]. In general, they favoring westernized food [16], their contemporary typical food choices back home lack in fruit and vegetables, however, are rich in fat, meat, starch [17,18]. In addition, physical inactivity is prevalent among Arab college students in which average weight and BMI of males is higher than in females, respectively [19]. Although there have been studies focusing on dietary habits of Arab college students in their home countries, there are an insufficient number of studies done to examine, discuss, or to analyze changes in dietary habits, food consumption, and lifestyle behaviors of Arab college students studying abroad. The aim of the study was to examine changes in dietary habits between males and females, and single vs. married Arab international students in the US. In addition, examine differences in food consumption patterns and lifestyle behaviors amongst these different groups as a secondary aim. The study hypnotized that female participants and those that are married will maintain healthier eating habits compared to males and singles, respectively, after relocating to their newly living environment.

METHODOLOGY

Study design and subjects

Questionnaire development

STATISTICS

Descriptive statistics included paired and independent t-tests, Pearson’s chi-square, and Fisher’s exact test were performed to estimate means and proportions differences between gender and marital status. A repeated-measures factorial (2X2) ANOVA was utilized to examine changes in the consumption of traditional/westernized food, differences regarding eating locations and preferences, and number of meals and snacks, methods of food before and after moving to the US between married and single students. Additionally, the aforementioned statistical tests controlled for age while examining gender differences. Spearman’s correlation coefficient test was performed to measure of the strength of an association between demographic variables and food behavior and intake. Both using the level of significance (P<0.05) as well as the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for windows (IBM SPSS, version 24, 2016) for data analysis were used.

RESULTS

| Characteristic | Total | N |

| Total | 95 | |

| Males | 69% | 66 |

| Females | 31% | 29 |

| Age | 25.6± 5.6 | 94 |

| Marital status | 91 | |

| Single | 45% | 41 |

| Married | 55% | 50 |

| Nationality | 94 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 82% | 77 |

| Kuwait | 13% | 12 |

| Jordan | 12% | 3 |

| Syria | 1% | 1 |

| Arab Emirates | 1% | 1 |

| Education status | 94 | |

| Graduate student | 40% | 38 |

| Undergraduate student | 41% | 39 |

| English language institute | 18% | 17 |

| Living location | 93 | |

| On campus | 12% | 10 |

| Off campus | 88% | 83 |

| Sponsorship | 91 | |

| Yes | 90% | 82 |

| No | 10% | 9 |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics.

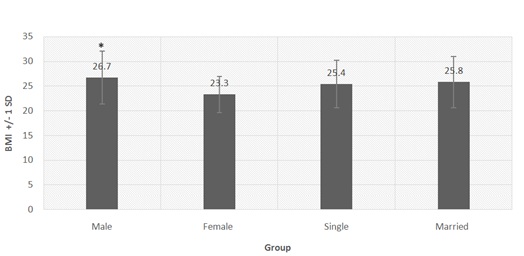

Figure 1: BMI mean of Arab international students (+/-1 SD).

Figure 1: BMI mean of Arab international students (+/-1 SD).Daily eating of traditional vs. westernized food before/after moving to the US

| Traditional Before |

Males n=64 (%) |

Females n=27 (%) |

Single n=41(%) |

Married n=50 (%) |

| Makboos/Kabsa | 64 | 55 | 54 | 59 |

| Flafel/Fuel | 59 | 31 | 61 | 43 |

| Pasta/Macaroni | 5 | 17 | 5 | 12 |

| Pastries/Fatayer | 14 | 10 | 10 | 16 |

| Taboli | 32 | 31 | 29 | 35 |

| Indian/Iranian/Mediterranean | 23 | 24 | 29 | 20 |

| Westernized Before | ||||

| Beef burger | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| Chicken burger | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Seafood | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Sandwiches | 15 | 7 | 14 | 12 |

| Spaghetti | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Pizza | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Burritos/Tacos | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Beans/Corn | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Bagels | 6 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| Traditional After | ||||

| Makboos/Kabsa | 12 | 21 | 12 | 18 |

| Flafel/Fuel | 26 | 24 | 27 | 25 |

| Pasta/Macaroni | 7 | 3 | 2 | 10 |

| Pastries/Fatayer | 2 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| Taboli | 21 | 27 | 53 | 33 |

| lIndian/Iranian/Mediterranean | 42 | 17 | 44 | 27 |

| Westernized After | ||||

| Beef burger | 36 | 14 | 48 | 12 |

| Chicken burger | 12 | 17 | 12 | 14 |

| Seafood | 6 | 14 | 46 | 6 |

| Sandwiches | 23 | 21 | 27 | 16 |

| Spaghetti | 7 | 7 | 9 | 2 |

| Pizza | 3 | 10 | 0 | 8 |

| Burritos/Tacos | 6 | 7 | 9 | 4 |

| Beans/Corn | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Bagels | 12 | 0 | 66 | 4 |

Table 2: Percentages of intakes from traditional and westernized food choices & cuisines (before/after).

| Gender | Marital Status | Age | BMI | Off/on Campus | Sponsorship | Academic Level | Time in US | |

| Milk and dairy | 0.275* | 0.039* | 0.179 | 0.282 | 0.932 | 0.977 | 0.698 | 0.082 |

| Dairy fat% | 0.628 | 0.151 | 0.472 | 0.834 | 0.015* | 0.952 | 0.114 | 0.226 |

| Dairy fortification | 0.398 | 0.408 | 0.95 | 0.38 | 0.129 | 0.549 | 0.561 | 0.628 |

| Bread | 0.485 | 0.738 | 0.269 | 0.585 | 0.989 | 0.096 | 0.847 | 0.273 |

| Fats and oils | 0.316 | 0.345 | 0.889 | 0.206 | 0.999 | 0.038 | 0.108 | 0.081 |

| Meat/legumes/eggs | 0.196 | 0.362 | 0.564 | 0.702 | 0.809 | 0.006* | 0.034* | 0.012* |

| Vegetables and fruit | 0.247 | 0.097 | 0.344 | 0.402 | 0.285 | 0.143 | 0.035 | 0.162 |

| Starches | 0.646 | 0.876 | 0.209 | 0.683 | 0.331 | 0.054 | 0.443 | 0.012 |

| Beverages | 0.874 | 0.761 | 0.021* | 0.397 | 0.959 | 0.815 | 0.457 | 0.088 |

| Snack food and desserts | 0.148 | 0.397 | 0.968 | 0.208 | 1.333 | 0.000* | 0.051* | 0.002* |

| Traditional before | 0.309 | 0.679 | 0.293 | 0.689 | 0.029* | 0.247 | 0.242 | 0.871 |

| Traditional after | 0.459 | 0.015* | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.143 | 0.482 | 0.109 | 0.8 |

| Westernized before | 0.067* | 0.238 | 0.183 | 0.286 | 0.464 | 0.697 | 0.542 | 0.235 |

| Westernized after | 0.085 | 0.021* | 0.011* | 0.468 | 0.674 | 0.611 | 0.27 | 0.379 |

| Cook before | 0.209 | 0.002* | 0.347 | 0.366 | 0.383 | 0.233 | 0.639 | 0.211 |

| Buy & prepare before | 0.349 | 0.362 | 0.897 | 0.199 | 0.111 | 0.369 | 0.558 | 0.838 |

| Neither before | 0.12 | 0.002* | 0.109 | 0.218 | 0.885 | 0.426 | 0.671 | 0.07 |

| Both before | 0.333 | 0.243 | 0.336 | 0.459 | 0.602 | 0.574 | 0.713 | 0.29 |

| Cook after | 0.582 | 0.000* | 0.013* | 0.841 | 0.724 | 0.144 | 0.515 | 0.355 |

| Buy & prepare after | 0.038* | 0.231 | 0.888 | 0.623 | 0.532 | 0.16 | 0.464 | 0.889 |

| Neither after | 0.515 | 0.125 | 0.215 | 0.299 | 0.705 | 0.587 | 0.609 | 0.077 |

| Both after | 0.052* | -.050* | 0.194 | 0.529 | 0.373 | 0.594 | 0.403 | 0.51 |

| Number of meals before | 0.564 | 0.615 | 0.075 | 0.586 | 0.267 | 0.061 | 0.673 | 0.274 |

| Number of meals after | 0.917 | 0.258 | 0.374 | 0.040* | 0.303 | 0.968 | 0.814 | 0.969 |

| Number of snacks before | 0.405 | 0.512 | 0.191 | 0.325 | 0.075 | 0.015* | 0.062 | 0.013* |

| Number of snacks after | 0.012* | 0.572 | 0.000* | 0.228 | 0.084 | 0.025* | 0.19 | 0.067 |

| Cook and eat at home | 0.816 | 0.003* | 0.087 | 0.017 | 0.301 | 0.732 | 0.709 | 0.164 |

| Eat out | 0.578 | 0.001* | 0.000* | 0.337 | 0.000* | 0.538 | 0.296 | 0.003* |

| Food availability | 0.424 | 0.456 | 0.366 | 0.542 | 0.563 | 0.061 | 0.955 | 0.487 |

| Exercising | 0.225 | 0.399 | 0.628 | 0.696 | 0.904 | 0.776 | 0.619 | 0.322 |

| Dieting | 0.259 | 0.056* | 0.698 | 0.704 | 0.008 | 0.093 | 0.386 | 0.821 |

| Supplementation | 0.343 | 0.372 | 0.631 | 0.138 | 0.112 | 0.775 | 0.429 | 0.459 |

| Time exercised | 0.072 | 0.302 | 0.949 | 0.741 | 0.072* | 0.797 | 0.137 | 0.945 |

| Change in eating pattern | 0.536 | 0.148 | 0.746 | 0.488 | 0.349 | 0.133 | 0.758 | 0.322 |

| Change in weight | 0.615 | 0.333 | 0.613 | 0.298 | 0.017 | 0.798 | 0.942 | 0.324 |

| Change in diet | 0.312 | 0.302 | 0.059* | 0.514 | 0.247 | 0.561 | 0.214 | 0.31 |

| I eat traditional home before | 0.838 | 0.921 | 0.437 | 0.593 | 0.086 | 0.859 | 0.022 | 0.02 |

| I eat traditional restaurant before | 0.878 | 0.478 | 0.977 | 0.998 | 0.449 | 0.58 | 0.767 | 0.133 |

| I eat traditional both before | 0.88 | 0.869 | 0.574 | 0.606 | 0.028 | 0.979 | 0.011 | 0.017 |

| I eat traditional home after | 0.501 | 0 | 0.74 | 0.292 | 0.631 | 0.363 | 0.354 | 0.346 |

| I eat traditional restaurant after | 0.463 | 0.003 | 0.791 | 0.264 | 0.791 | 0.45 | 0.904 | 0.558 |

| I eat traditional both after | 0.878 | 0.113 | 0.489 | 0.4 | 0.657 | 0.7 | 0.165 | 0.297 |

| I eat westernized home before | 0.26 | 0.047 | 0.184 | 0.457 | 0.129 | 0.87 | 0.713 | 0.417 |

| I eat westernized restaurant before | 0.351 | 0.017 | 0.08 | 0.638 | 0.383 | 0.251 | 0.615 | 0.68 |

| I eat westernized both before | 0.952 | 0.463 | 0.335 | 0.41 | 0.409 | 0.186 | 0.629 | 0.42 |

| I eat westernized home after | 0.743 | 0.008 | 0.079 | 0.702 | 0.417 | 0.637 | 0.257 | 0.118 |

| I eat westernized restaurant after | 0.212 | 0.01 | 0.851 | 0.592 | 0.228 | 0.573 | 0.43 | 0.504 |

| I eat westernized both after | 0.382 | 0.811 | 0.748 | 0.376 | 0.448 | 0.887 | 0.714 | 0.28 |

Table 3: Measure of association at p≤0.05* chi-square.

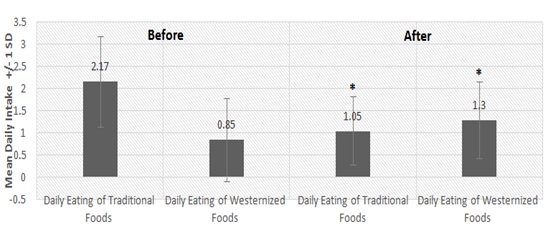

Figure 2: Daily eating of traditional vs. westernized food for total participants.

Figure 2: Daily eating of traditional vs. westernized food for total participants.| Traditional Food | Before | After | P-value |

| Males | 2.19±0.848 | 1.01±0.734 | 0.013 |

| Females | 2.11±1.31 | 1.11±0.847 | 0.000 |

| Single | 2.1±0.831 | 0.75±0.700 | 0.374 |

| Married | 2.19±1.15 | 1.15±0.168 | 0.000 |

| Total participants` | 2.17±1.025 | 1.05±0.771 | 0.001 |

| Westernized Food | |||

| Males | 1.00±0.894 | 1.47±0.909 | 0.005 |

| Females | 0.556±0.983 | 0.944±0.639 | 0.078 |

| Single | 0.950±0.825 | 1.75±0.716 | 0.298 |

| Married | 0.750±0.950 | 1.03±0.860 | 0.000 |

| Total participants | 0.85±0.940 | 1.30±0.861 | 0.001 |

Table 4: Daily eating of traditional vs. westernized food before/after moving to the US by study groups (Mean±SD at 0.05 level of significance).

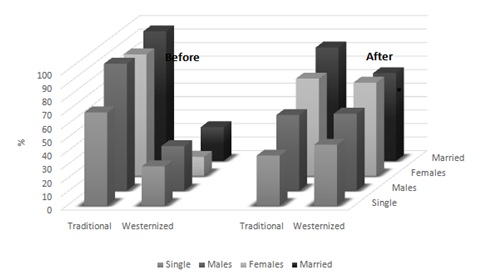

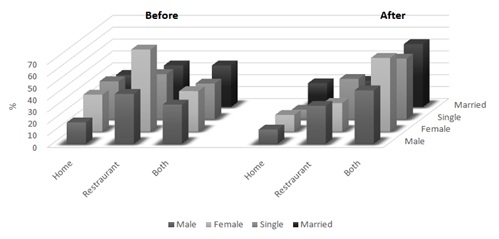

Figure 3: Percentages of daily eating of traditional/westernized food (before/after).

Figure 3: Percentages of daily eating of traditional/westernized food (before/after).

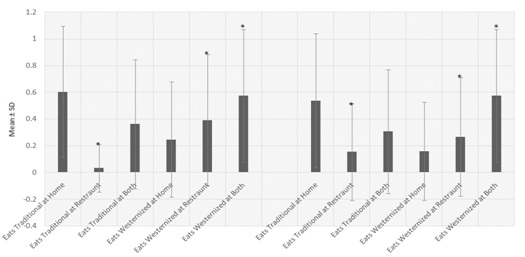

Eating traditional vs. westernized food at home/local restaurant

| Gender | Marial Status | Age | BMI | Off/on Campus | Sponsorship | Academic Level | Time in US | |

| Milk and dairy | 0.068 | 0.278* | 0.071 | -0.067 | -0.084 | -0.076 | -0.108 | 0.044 |

| Dairy fat% | -0.007 | 0.003 | 0.084 | 0.16 | -0.099 | -0.019 | -0.221* | 0.023 |

| Dairy fortification | 0.133 | -0.134 | -0.136 | 0.126 | 0.249* | -0.049 | -0.042 | 0.053 |

| Bread | -0.003 | 0.08 | 0.117 | 0.052 | 0.05 | 0.122 | 0.005 | 0.079 |

| Fats and oils | 0.12 | 0.188 | 0.066 | -0.157 | -0.029 | 0.122 | 0.216 | -0.08 |

| Meat/legumes/eggs | 0.046 | 0.128 | -0.062 | 0.293* | -0.063 | 0.187 | 0.035 | 0.006 |

| Vegetables and fruit | -0.002 | 0.389** | 0.261* | -0.035 | -0.177 | 0.204 | 0.072 | 0.111 |

| Starches | 0.087 | 0.154 | -0.05 | 0.025 | -0.134 | 0.092 | 0.167 | -0.061 |

| Beverages | -0.036 | -0.141 | -0.189 | 0.036 | -0.042 | -0.174 | 0.177 | -0.185 |

| Snack food and desserts | 0.173 | -0.015 | -0.122 | 0.092 | -0.038 | 0.296* | 0.187 | 0.175 |

| Traditional before | -0.108 | 0.042 | 0.181 | -0.059 | -0.013 | -0.185 | -0.032 | -0.047 |

| Traditional after | 0.026 | 0.306** | 0.259* | 0.094 | -0.203 | -0.059 | -0.13 | 0.281* |

| Westernized before | -0.261* | -0.188 | 0.042 | 0.106 | -0.092 | DISCUSSION

This study investigated changes in eating habits, differences in food consumption, and lifestyle behaviors among Arab international college student’s gender and marital status residing in Northeast Ohio during 2010.

Daily intake of traditional and westernized foodThe purpose of classifying food choices as traditional and westernized was to characterize participants’ daily food selections when they are living abroad, in a different environment and cultural food settings. Specifying what food items are considered traditional and or westernized is complex. For instance, rice with meat (often chicken) is called “Makboos” in Kuwait, called “Baryani lamb/chicken” in some Indian culture but is not an American food. Beef stew is popular in the US, and is known as “MaraqLaham” in Kuwait. However, hot dogs, burgers, and pizza are not considered cultural food in the Arab world. Americans in the US may occasionally eat Indian food, but not necessary prepare it at home. In addition, there are food items in-between such as scrambled eggs, milk and cereal, which are consumed by many cultures and ethnicities around the world. Nevertheless, every ethnicity is linked to unique foods and dishes connected through generations, time, and environment [13]. The study referred to traditional food as unique cultural food items or dishes, regardless of contents, consumed by specific ethnicity, made from scratch, cooked and usually eaten at home with people. It is already known that Arab Gulf region countries consume mixed diets including traditional, fast food, and cuisines from all over the world including the US [15]. This is related to improved economy, food availability and food importation [18,21]. Moreover, several studies indicated nutritional intake and food behavior issues related to increase westernized fast food intake among Arab college students back home, regardless of gender or marital status [15,20-22]. Previous research indicates pre-adaptation to changes in the diet when living abroad, but these studies were not necessary looking for or detecting shifts in diet or cultural food selections among Arab populations back home. Shifts in the diet are not always clear or possible in Arab nations. While results reflected a significant shift toward westernized food consumption compared to before moving to the US in which traditional food consumption was dominant among all participants [23-25]. On the other hand, westernized food consumption became significantly increased after moving to the US accompanied by a significant decrease in traditional food consumption. This has to do with acculturation and integration into a new host country, which involves changes in dietary habits into mixed food or westernized diet than traditional diets [13]. Moreover, changing in eating patterns and life style. The current study findings helped distinguished between mixing a diet of traditional and westernized back home and living abroad by college students. Before moving to the US, daily consumption of westernized food among all participants was humble, in which traditional food was more dominant. Despite that consumption of westernized food significantly replaced traditional food choices after moving to the US. However, some participants, such as those married, and females in general maintained traditional food as the dominant choice (Figure 3). This may be attributed to cooking and food preparation skills, as some students may be poorly equipped to prepare their own meals [26,27], a consequence of having left the family home and taking on the responsibility of food purchasing and preparation [7]. Moreover, limited time, and/or limited knowledge to shop and how to prepare food also affects maintaining traditional food consumption [4]. Both married and female participants relied on their cooking skills, where as single and male participants relied on using buy and prepare methods after moving to the US (Figure 6). Scarcity of traditional food sources in the US is another challenge that international students face when they relocate. If available, imported traditional food pricing in the host country can become prohibitive, which encourages shifting from typical dietary habits and food choices [13]. Around 40% of total respondents reported traditional food scarcity, or not available in stores (~10%), (Figure 5).

Food behavior and location after moving to the USInternational student’s food behavior fluctuates as a result of acculturation and adjustments to their newer living environment, including food access [3]. The results of this study indicated a significant increase in food consumption from local westernized restaurants, eating out, eating on campus and in public among total participants after moving to the US (Table 9). Married participants did not decrease their eating at home compared to other groups in the study (Figure 13). Eating alone increased among all participants after relocating in the US, which may have to do with lack of communication skills related to language barriers, and stress due to social and cultural changes [28] (Table 9). The results revealed variations regarding where each subgroup eats. The majority of participants ate traditional food in both restaurants and at home, particularly, those married and females after they moved to the US (Figure 13). This may be attributed to the scarcity of places that sell traditional food, or the need of socializing in their host environment. The consumption of westernized food at restaurants was greater in single vs. married participants. As for eating at home, married participants were more likely to eat either types of food at home in comparison to single participants. In addition, married participants tended to maintain the habit of eating at home after moving to the US. This is in agreement with previous research in which married international students reported as being more settled and self-sufficient as they would be less likely to eat outside their residence [5]. Hence, they demonstrate a higher likelihood for maintaining traditional food consumption compared to single participants in the current study.

Figure 13: Eating traditional food at home/restaurant by Arab international students. Figure 13: Eating traditional food at home/restaurant by Arab international students.Types of foods consumed after moving to the USThe intake of traditional food delicacies (Makboos/kabsa,falafel, fatayer, taboli, etc) declined by 40% for the total group (Table 2). Similar to other research, international students may be used to consuming westernized foods including fast foods back in their home country, which might become part of their predominant eating pattern while they are residing in the US [15]. A previous study has indicated that the consumption of westernized fast food is already high among Arab nations in the Gulf region [15,16]. Nonetheless, other factors such as maintenance of current eating patterns, or rejecting new foods (food neophobia) after relocating to the US, may be possible [29].

Daily consumption (one cup or more) from food groupsThe majority of participants were consuming regular (2% fat) dairy in the form of milk and flavored milk. Females and married participants consumed traditional milk derivative (Laban), whereas intake of cheese was higher among males. Dairy products such as low (1%) fat or skim would help in weight control (Table 11). In general, in the Arab world, the proportion of energy from milk to total energy intake is equivalent to one-quarter of energy comes from carbohydrate intake according to FAO fact balance sheet [18]. As indicated in previous literature, in Arabic countries, including the Gulf region, carbohydrates in the form of rice and wheat are considered to be the major constituents of the diet [18]. Overall, cereals have shown to contribute the most energy in the typical Arab diet [30]. There were similar findings in this study, as pita bread was the most common consumed by all groups. Breakfast cereal and grains (non-enriched) intake was seen more among married vs. single participants. However, married participants consumed a variety starches including white and brown rice, pasta, mashed and baked potato, whereas singles consumed more white rice and fried potato. The results are similar to Eva et al., in which married individual was more likely to eat a varied diet than singles [31]. Some studies indicate that meat, chicken, fish, and eggs are major constituents of the typical Arab diet [11,18,32]. In this study, white meat was consumed by the majority of respondents. More nutrient-dense meat choices such as seafood were considered the least type of meat consumed by respondents. Egg consumption was reported by all participants at similar percentages. Fat from butter, lard, and cream was consumed almost equally amongst all participants; however, consumption of fat from oils such as (olive/canola/corn) was greater among females vs. males, as well as married vs. singles (Table 11). Although we did not evaluate macro/micro nutrients, this may indicate that married and females diet contained more unsaturated fat compared to males and singles, which is considered healthy fat. When looking at the fruit and vegetables group, married and female participants’ intakes were greater than single and male participants, respectively (Table 11). This may explain the trend (p≤0.09 [r=0.389, p≤0.01]) in fruit and vegetables intake, along with cocking skills (p≤0.002 [r=0.371, p≤0.01]) among married participants. Perez-Cueto et al., observed that married people appeared to spend more time cooking and preparing food at home than eating out [5]. In addition, female college students having more habitual vegetable consumption behaviors compared to college males [33]. Similar to previous results in Kuwaiti college students, the current study reveals that there is a high carbonated and caffeinated beverage intake overall [25]. In contrast, the current study participants’ average daily water intake was less than four cups (Table 11).

Impact of relocating on food choices and intakeRelocating usually affects international students’ food choices and eating habits, due to their unstable life styles such as changes in eating patterns, physical and social activities, and food availability [3]. Our current findings revealed that the majority of participants decreased fruit, vegetable, and beans intake, while an increased fat (mayonnaise) intakes. Papadaki A and Scott JA investigated changes in the eating habits of 80 male and female international students that relocated to Greece. The majority (85%) reported their eating habits shifted from more to less calorie-dense including decreased fruit, vegetables, and bean consumption, while increasing fat (mayonnaise) intake [7]. Perez-Cueto et al., observed gender and marital status difference in dietary habits of relocating international students (n=158) in Belgium. Married students increased their consumption of fruits and vegetables by 2.1 times compared to single students. In addition, females, marginally (P=0.053), reduced their consumption of sugar and confectionary more than males [5]. Most respondents of this study reported unchanged bread consumption after moving to the US. Married intakes from fruits and vegetables, and fats and oils were higher than that of single participants. On the hand, females, intake from fruits and vegetables was slightly lower than that of males (Table 10). Consumption of oils was higher among females and married compare to males and singles, respectively (Tables 10 and 11).

Change in eating pattern, meal and snack number, and lifestyle behaviorsCahill C et al., described that international students in the US have experienced significant eating pattern and lifestyle changes such as less physical activity [3]. This agrees with our studies finding that (~65%) of all participants reported a change in their eating pattern (Figure 8). The majority of respondents’ daily meal number declined in which snacking was increased (Table 7). Similarly, replacing a meal by a snack was reported among college students in Saudi Arabia [34]. Although exercising was related with gender (Table 3), about 50% of our participants do not exercise (Figure 12). Lack of physical activity has been reported among male and female college students in Kuwait [35-37]. Moreover, dieting practice was not common among the majority of respondents in this study, which agrees with the current literature [35,38]. Nonetheless, some married and female participants reported having weight watcher or diabetic diets (Table 7). Dieting was also associated with marital status (Table 3). Nutritional supplements were rarely used by our participants (Figure 11), compared to 62% (n=502) US college students who used supplements on a regular basis [39]. Distinctions in food intake, food choices, behavior, and lifestyle among the study groups does not necessary explain their BMI classifications. In this study, the average BMI of males was higher than that of females. Other research suggests reasons why females were of normal BMI, females have shown healthier dietary intake patterns than males [5], eating more fruits and vegetables, fiber rich products, and reduced salts than males [21]. Participants of this study reporting on weight status (percentage of gaining, loss, or no change) after relocating was almost proportionally equal, which was also found among 80 participants reported by Papadaki A and Scott JA [7]. Nutritional and physiological changes which occurs during college years may contribute to abnormal BMI (overweight and obesity) [3,4], among international students. In addition, caloric intake and physical activity are known to influence BMI; however in this study caloric intake was not assessed. STRENGTHSThis study described changes in dietary habits, food consumption, and lifestyle behaviors among Arab college students relocated to the US. The study also examined the shift in their diet, food choices, and food behavior. This study’s findings help encourage further research investigation in areas not covered or lack by this study. LIMITATIONSThe study was restricted to a certain ethnicity and location in which the results cannot be generalized. The ratio and proportion with regards to gender along with marital status were not evenly distributed. The survey question on marital status did not distinguish whether married participants were married to another participant, which their responses to the questions might be the same, or a particular question been answered twice. The developed questionnaire was not validated with 24-hour recall. Only three participants filled the attached 24-hour recall in which two were incomplete. Most of the participants complained about the length of the survey. The researcher and the team involved decided to use an in-person method for distributing the surveys, which was poorly tracked. Caloric intake of participants was not estimated, hence, associating participants’ changes in dietary habits with caloric intake was missed in the study. Some questions in the questionnaire were not addressed efficiently. Such as the physical activity question, which was not addressed clearly (30+ minutes of moderate activity on 5+ days/week, 20+ minutes of vigorous activity on 3+ days/week). Questions about change in eating pattern may have been confusing to participants. The question about number of snacks a day did not distinguish between healthy and non-healthy snack choices. Moreover, information regarding BMI, intake from food groups before relocating was not included in the questionnaire. The study did not compare with a sample of college students back home in the Arab Gulf region. FUTURE DIRECTIONSeveral studies have shown that international students are significantly susceptible to dietary and or food behavior changes characterized by less varied, unbalanced food consumption. Future studies can examine food neophobia among Arab international students, which characterized as selective eating, consumption of low variety of foods, and eating few foods [29]. Evaluating relationships between dietary and lifestyle behaviors and risks of chronic diseases among Arab college students studying abroad is another important area. It has been documented that poor dietary and lifestyle behaviors is related to increasing prevalence of obesity and non-communicable diseases among Arab nations [40-42]. CONCLUSIONThe participants of our study experienced significant changes in their dietary intake, food choices, and eating patterns once relocating to the US. Westernized food sources increased and replaced traditional (cultural) foods. It is important to illustrate health and nutrition changes affecting people who live temporary abroad which may be caused by changing the type of food consumed from traditional to westernized or vice versa and does not necessarily mean that either one of these foods is unhealthy. However, maintaining balanced dietary intake from food groups, as well as healthier food choices must be taken into consideration regardless of mixing the diet of traditional and westernized. In general, females and married participants’ food choices were more likely to be healthier than males and singles. Married and female participants were more likely to maintain traditional food choices and cook/eat at home compared to males and singles. These two findings agree with the study hypothesis that married and female participants will be healthier than males and single participants, respectively. Females’ and married participants’ dietary intake was more diversified in consuming more vegetables fats/oils, fortified low fat % 1 and skim milk, as well as a variety of starches. Furthermore, female participants in this study showed a normal BMI range. CONFLICT OF INTERESTNo conflict of interest involved in this study. REFERENCES

Citation: Al-Farhan AK, Kemnic T, Becker T, Caine-Bish N, Burzminski N, et al. (2018) Changes in Dietary Behavior of Arab International Students in the US. J Food Sci Nut 4: 033. Copyright: © 2018 Abdulaziz Kh Al-Farhan, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!

|