Arrests, Fatality Crashes, Before and After Missouri V Mcneely Law in Texas

*Corresponding Author(s):

Ashraf MozayaniAdministration Of Justice, Texas Southeren University, Houston, Texas, United States

Tel:+1 7133137332,

Email:Ashraf.Mozayani@tsu.edu

Abstract

Background

Prior to Missouri vs. McNeelycase (2013), police officers in Texas were allowed to obtain blood evidence from a suspected impaired driver without obtaining a search warrant. After Schmerber vs. California (1966) the Court allowed police officer to collect blood evidence without a warrant under the exigent circumstances exception to prevent the destruction of alcohol through the body’s natural metabolic processes. In McNeely, the Court ruled that police must generally obtain a warrant before subjecting an impaired driving suspect to a blood test, and that the natural metabolism of blood alcohol does not establish a per exigency that would justify a blood draw without a warrant. The Court left open the possibility that the “exigent circumstances” exception to the general requirement might apply in some impairment driving cases. However, District Attorney’s in Texas issued a mandate after the McNeely ruling requiring officers to obtain a search warrant when collecting blood evidence from all impaired driving suspects.

Objective

This article analysis the McNeely ruling and attempts to determine if there is a relationship between impairment arrests and fatality crashes in Texas before and after the ruling.

Study Design

Literature Review

Method

A review of arrest and fatality data was conducted before and after the McNeely ruling.

Results

Texas District Attorney’s began requiring officers to obtain a search warrant before collecting blood evidence from a suspected impaired driver after the McNeely ruling.

Limitations

The design of data collected for this study has limitations; on the length of time evaluated. Over the ten year period technology for gathering data improved.

Conclusion

Impairment arrests declined in Texas after it became mandatory to obtain a warrant for blood evidence.

This study examines the relationship between impairment arrests, fatality crashes and the use of the exigent circumstances under the exception clause of the 4th Amendment. Blood collection has been debated and litigated at the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOUTS) and two important cases has affected how law enforcement must proceed as it relates to impaired drivers. In Schmerber v. California (1966), the SCOTUS declared the Fourth and Fifth Amendments were not violated when law enforcement collected blood evidence without a warrant. However, in 2013 in Missouri v. McNeely, the ruling stated collecting blood evidence constitutes a search and violates the search and seizure clause of the Fourth Amendment. Data for the study was collected from the three largest counties in Texas; Harris, Dallas and Tarrant. The data was request through an open records request, from the District Attorney’s office of each county. The data was stored in their Justice Information Management System (JIMS). The study is guided by the following research questions: (1) Is there a significant difference in DUI arrests after the Missouri v. McNeely ruling? (2) Is there a significant difference in fatality crashes after the Missouri v. McNeely ruling? (3) Is there a significant difference in the application of exigent circumstances before and after the Missouri v. McNeely ruling? The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (S.P.S.S.) is used to analyze data on arrests and fatality crashes from 2007 to 2016. The study will conclude that the McNeely ruling has affected DUI arrests, and the directives of District Attorneys directly impact DUI arrests and fatality crashes. Significant to this study is the fact that although the number of arrests declined, the data showed after the McNeely ruling the decline in arrests was more rapid. The number of impairment arrests in Texas annually prior to McNeely was an average of 89,473, which fell to an average of 70,438 after the ruling. Therefore, the effects of requiring a search warrant before collecting blood evidence produced an outcome of fewer impairment arrests by police officers.

The data also illustrated after the McNeely ruling there was an increase in fatality crashes. The number of fatal crashes in Texas annually prior to McNeely was an average of 2,943, which increased to an average of 3,287 after the ruling. Also, prior to McNeely, police officers in Texas could utilize exigent circumstances and forgo a search warrant when collecting blood evidence. After the McNeely police in Texas had to obtain a search warrant when collection blood evidence.

The results of the study indicated that there is a statistically significant relationship between impairment arrests and fatality crashes before and after the McNeely ruling in Texas. Finally, the results indicated that overall, Missouri v. McNeely had a significant effect on DWI arrests and fatal crashes in Texas.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The possibility of a fatal crash involving a drunk driver is a glaring danger for every individual driving on an American roadway [1]. This statement provokes the questions; are more impaired drivers being arrested since the McNeely vs. Missouri ruling, and has the ruling decreased fatalities? Since the creation of the automobile, resources and programs have been allocated and developed to reduce the number of impaired drivers as well as fatal crashes on roadways. One such program that benefits victims and law enforcement, without bias, is the Selective Traffic Enforcement Program (S.T.E.P.) created in 1996, which utilizes grants to pay for law enforcement overtime to reduce driving while intoxicated, speeding, failure to use occupant restraint systems (seatbelt), traffic violations at intersections, and enforcement of state and local ordinances on driving while using cell phones [2].Victim support programs like Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), Students Against Destructive Decisions (SADD), and Remove Intoxicated Drivers (RID), work together with communities and law enforcement agencies in an attempt to address traffic safety concerns before a drunk driver is arrested and a fatality crash occurs. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA, 2016) [3] “In 2014, there were 9,967 people killed in alcohol-impaired driving crashes, an average of 1 alcohol-impaired-driving fatality every 53 minutes.” In spite of the efforts to reduce and prevent impaired driving and fatal crashes, they continue to be an issue of enormous importance for future criminology studies [4]. Therefore, this study seeks to determine if the more rigorous standard established by the McNeely ruling when utilizing exigent circumstances, benefited or hindered attempts to reduce impaired driving and fatal crashes.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE

Prior to McNeely, Schmerber v. California (1966) allowed constitutional procedures for law enforcement when collecting specimens from suspects [5]. Police obtained blood evidence without a warrant based on the exigent circumstance exception, which allows police to obtain evidence before it is destroyed through the natural metabolic process [6]. Missouri v. McNeely (2013) ruled that police collected blood evidence constituted a search, and police must generally obtain a warrant before subjecting citizens suspected of impaired driving to a blood test. Although, the Court left open the possibility that the “exigent circumstances” exception may apply in some impaired driving cases, [7] District Attorneys in Texas mandated that collecting any blood evidence required a search warrant. Therefore, did the McNeely ruling affect impairment arrests and fatality crashes in Texas?.

DATA COLLECTION

The data was collected over a ten year period, six years prior to the McNeely ruing (2007 – 2012), and four years after the McNeely case. Statistical significance is determined based on an alpha of .05. The Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is used to analyze the differences between arrests and fatalities [8]. The one-way ANOVA was used to compare the mean, and determine if there is a statistically significant difference. The Turkey test identified where the difference occurred between the sampled areas. The content analysis identified policy patterns, characteristics or other important relationships that existed between the selected areas. The content analysis reviewed the exigent circumstances policy from each District Attorney’s Office. One open records request was sent to the Harris and Tarrant District Attorney’s Office and several to the Dallas County District Attorney. The DAs office received the request because in Texas, the District Attorney is the agent responsible for accepting criminal charges in each County [9]. The requests sought information on all arrests made for driving while intoxicated within the county from 2007 through 2016. The open records request also sought the directive issued to law enforcement after the McNeely ruling on how to collect blood evidence from violators. The information requested was not collected in a consistent manner and is maintained differently by each agency. Each agency is required to send annual reports to the Uniformed Crime Reports (UCR) system [10]. The arrest data, obtained from Dallas County is entered in the data system in an inadequate manner and not easily accessed. For example, impaired driving arrests have not (over the request time period) always been differentiated by alcohol or drugs. As a result of this limitation, Dallas County requested payment for the man hours required to retrieve the information.

RESULT OF STATISTICAL ANALYSES

The data was collected over a ten year period, six years prior to the Missouri v. McNeely ruling (2007 – 2012), and four years after the McNeely case. Over the ten year study period, fatality crashes increase in each county. Harris County had a 23% increase from the 2007 through 2016. Dallas County had a 36% increase over the same time period. Tarrant County had the lowest increase with 8%. From 2007 through 2017, a total of 261,315 impairment arrests were made within the sample pool in Texas. Harris County had a decrease of 3% over the ten year time period. In 2011 Harris County had the highest number of DUI arrests with 13,963 and the lowest number in 2014 with 9,798 or a 42% decrease. Dallas County had a decrease of 8% over the ten year time period. In 2008 Dallas County had the highest number of DUI arrests with 8,719 and the lowest number in 2012 with 6,284 or a 38% decrease. Tarrant County had a 17% decrease over the ten year time period. In 2015 Tarrant County had the highest number of DUI arrests with 11,070 and the lowest number in 2016 with 5,328 or a 90% percent decrease (Tables 1-7).

|

U.S. |

Texas |

Harris co |

Dallas co |

Tarrant co |

||||||

|

2007 |

301.2m |

7.40% |

23.83m |

17% |

3.9m |

18% |

2.38m |

8.40% |

1.71m |

18.20% |

|

2008 |

304.1m |

24.31m |

3.98m |

1.23m |

1.75m |

|||||

|

2009 |

306.8m |

24.8m |

4m |

2.45m |

1.79m |

|||||

|

2010 |

309.3m |

25.26m |

4.1m |

2.37m |

1.8m |

|||||

|

2011 |

311.6m |

25.64m |

4.18m |

2.4m |

1.84m |

|||||

|

2012 |

314m |

26.08m |

4.26m |

2.45m |

1.88m |

|||||

|

2013 |

316.2m |

26.48m |

4.35m |

2.48m |

1.9m |

|||||

|

2014 |

319.6m |

26.95m |

4.45m |

2.5m |

1.94m |

|||||

|

2015 |

321m |

27.45m |

4.5m |

2.55m |

1.98m |

|||||

|

2016 |

323.4m |

27.9m |

4.6m |

2.58m |

2.02m |

Table 1: Population Demographics 2007 – 2016.

Source: United States Census Bureau 2007 - 2016

|

United States |

% Change |

Texas |

||||

|

Year |

Non-Alcohol |

Alcohol |

Non-Alcohol |

Alcohol |

||

|

2007 |

37,248 |

13,003 |

3,098 |

607 |

||

|

2008 |

34,017 |

12,818 |

↓ |

3,118 |

639 |

↑ |

|

2009 |

30,797 |

11,924 |

↓ |

2,821 |

630 |

↓ |

|

2010 |

30,196 |

11,237 |

↓ |

2,781 |

680 |

↑ |

|

2011 |

29,757 |

11,207 |

↓ |

2,804 |

692 |

↑ |

|

2012 |

30,800 |

10,947 |

↓ |

3,037 |

662 |

↓ |

|

2013 |

30,057 |

11,126 |

↑ |

3,064 |

697 |

↑ |

|

2014 |

28,989 |

15,479 |

↑ |

3,190 |

715 |

↑ |

|

2015 |

32,166 |

16,484 |

↑ |

3,186 |

665 |

↓ |

|

2016 |

34,439 |

17,538 |

34% Increase |

3,404 |

638 |

5 % Increase |

|

Total |

318,466 |

131,763 |

→ |

30,503 |

6,625 |

487,357 |

Table 2: Non-Alcohol and Alcohol Fatalities U.S. and Texas, 2007 – 2016.

Source: Uniform Crime Report 2007 - 2016.

|

Year |

Harris |

% change |

Dallas |

Tarrant |

||

|

2007 |

339 |

211 |

146 |

|||

|

2008 |

341 |

↑ |

232 |

↑ |

133 |

↓ |

|

2009 |

317 |

↓ |

155 |

↓ |

132 |

↓ |

|

2010 |

339 |

↑ |

173 |

↑ |

125 |

↓ |

|

2011 |

353 |

↑ |

174 |

↑ |

136 |

↑ |

|

2012 |

333 |

↓ |

192 |

↑ |

117 |

↓ |

|

2013 |

351 |

↑ |

206 |

↑ |

129 |

↑ |

|

2014 |

381 |

↑ |

222 |

↑ |

138 |

↑ |

|

2015 |

368 |

↓ |

239 |

↑ |

140 |

↑ |

|

2016 |

420 |

23 % Increase |

288 |

36% Increase |

158 |

8% Increase |

|

Total |

3542 |

2092 |

1354 |

6988 |

Table 3: Fatality Crashes in Texas by County, 2007 – 2016.

Source: Texas Department of Transportation 2007 – 2016.

|

Observed Fatalities |

Harris Co. |

Dallas Co. |

Tarrant Co. |

Total |

|

pre McNeely(2012) |

333 |

192 |

117 |

642 |

|

post McNeely(2014) |

381 |

222 |

138 |

741 |

|

Total |

714 |

414 |

255 |

1383 |

|

Expected Arrests |

Harris Co. |

Dallas Co. |

Tarrant Co. |

|

pre McNeely(2012) |

331 |

192 |

118 |

|

post McNeely(2014) |

382 |

221 |

137 |

Table 4: Chi – square: w/Contingency Table (Fatalities).

|

Fatalities |

Harris Co. |

Dallas Co. |

Tarrant Co. |

||

|

2007 |

339 |

211 |

146 |

||

|

2008 |

341 |

232 |

133 |

||

|

2009 |

317 |

155 |

132 |

||

|

2010 |

339 |

173 |

125 |

||

|

2011 |

353 |

174 |

136 |

||

|

2012 |

333 |

192 |

117 |

||

|

2013 |

351 |

206 |

129 |

||

|

2014 |

381 |

222 |

138 |

||

|

2015 |

368 |

239 |

140 |

||

|

2016 |

420 |

288 |

158 |

||

|

2017 |

437 |

267 |

167 |

||

|

Total |

3979 |

2359 |

1521 |

7859 |

|

|

Mean |

362 |

214 |

138 |

|

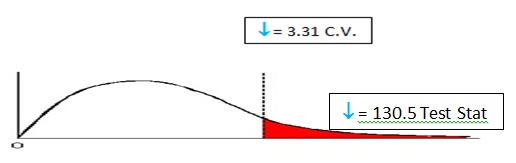

Anova: Single factor |

||||||

|

SUMMARY |

||||||

|

Groups |

Count |

Sum |

Average |

Variance |

||

|

Harris Co. |

11 |

3979 |

361.7272727 |

1395.218182 |

||

|

Dallas Co. |

11 |

2359 |

214.4545455 |

1661.472727 |

||

|

Tarrant Co. |

11 |

1521 |

138.2727273 |

206.4181818 |

||

|

Anova |

||||||

|

Source of variation |

ss |

df |

Ms |

F |

P-Value |

F Crit |

|

Between Groups |

283891.1515 |

2 |

141945.5758 |

130.5003037 |

1.58E-15 |

3.31583 |

|

Within Groups |

32631.09091 |

30 |

1087.70303 |

|||

|

Total |

316522.2424 |

32 |

||||

|

F-Critical-3.31 |

||||||

|

F-sat-130.5 |

Table 5: ANOVA.

|

Fatalities |

Harris |

Dallas |

Tarrant |

||

|

2007 |

339 |

211 |

146 |

||

|

2008 |

341 |

232 |

133 |

||

|

2009 |

317 |

155 |

132 |

||

|

2010 |

339 |

173 |

125 |

||

|

2011 |

353 |

174 |

136 |

||

|

2012 |

333 |

192 |

117 |

||

|

2013 |

351 |

206 |

129 |

||

|

2014 |

381 |

222 |

138 |

||

|

2015 |

368 |

239 |

140 |

||

|

2016 |

420 |

288 |

158 |

||

|

2017 |

437 |

267 |

167 |

||

|

Xbars(sample mean) |

361.7272727 |

214.4545455 |

138.272727 |

||

|

s^2(sample var) |

1395.218182 |

1661.472727 |

206.418182 |

||

|

xbar bar(Grand mean) |

238.1515152 |

f-test static |

130.5003 |

||

|

Group |

3 |

s^2_pooled |

1087.703 |

||

|

Observation |

11 |

s^_xbar |

12904.143 |

||

|

Total obser |

33 |

f-critical |

3.32 |

||

|

F_df_num |

2 |

||||

|

F_df_num |

30 |

||||

|

Turkey-kramer procedure |

|||||

|

Qu-critical |

3.49 |

||||

|

alpha |

0.05 |

||||

|

Q_df_num |

3 |

||||

|

Q_df_den |

30 |

||||

|

Comparison |

Absolute |

Critical Range |

Means Diff |

||

|

Harris/Dallas |

147.2727 |

34.70437709 |

> |

Yes |

|

|

Harris/Dallas |

223.4545 |

34.70437709 |

> |

Yes |

|

|

Harris/Dallas |

76.1818 |

34.70437709 |

> |

Yes |

Table 6: Post Hoc Tukey Kramer.

|

Year |

United states |

Texas |

||

|

2007 |

947,116 |

88,236 |

↑ |

|

|

2008 |

1,035,769 |

↑ |

90,066 |

↑ |

|

2009 |

1,063,940 |

↑ |

93,856 |

↓ |

|

2010 |

1,035,708 |

↓ |

93,533 |

↓ |

|

2011 |

902,425 |

↓ |

85,715 |

↓ |

|

2012 |

864,815 |

↓ |

85,436 |

↓ |

|

2013 |

782,603 |

↓ |

78,352 |

↓ |

|

2014 |

838,725 |

↑ |

70,482 |

↓ |

|

2015 |

783,473 |

↓ |

64,971 |

↓ |

|

2016 |

806,369 |

↑ |

67,950 |

↑ |

|

Total |

9,060,943 |

17% Decrease |

818,597 |

30% Decrease |

Table 7: DUI Arrests in the U.S. and Texas 2007 – 2016.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics 2007 – 2016

DISCUSSION

The main theory applied to this study is deterrence, based on the perspectives of many groups to include policy makers, activist groups, law enforcement, etc. Therefore, the first research question attempted to analyze whether the ruling had an adverse impact as it relates to arresting impaired drivers. The results were: the null hypothesis was rejected. There was sufficient evidence to conclude the ruling did reduce impairment arrests in Texas.

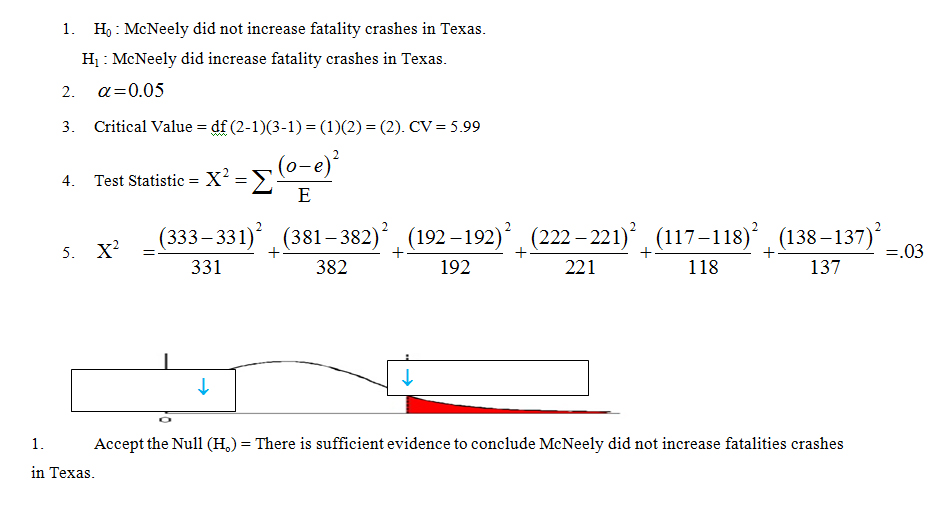

The second research question examines if there is a significant difference in fatality crashes after the Missouri v. McNeely ruling? This research question was chosen to determine if law enforcement were removing fewer impaired drivers, thereby creating a situation that contributed to fatality crashes. The results were to retain the null hypothesis. There is sufficient evidence to conclude the ruling did not increase fatality crashes in Texas.

The third research question, is there a significant difference in the application of exigent circumstances before and after the Missouri v. McNeely ruling? The directive analyzed the mandate law enforcement received from the District Attorney’s Office relating to collecting blood evidence [11]. It was found that there was significant and significant difference in the use of exigent circumstances in Texas.

IMPLICATIONS

The issue of protecting individuals from the overreach of the government, the rights to be free from unreasonable search and seizure remains an important principle of freedom [12]. However, the third research question attempts to ascertain if the utilization of an approved exception to 4th amendment requirements of a warrantless search changed after the ruling. The results were found as positive. The use of exigent circumstances was found to be different in each county. The study examines DUI arrests and fatality crashes before and after Missouri v. McNeely ruling. It was found DUI arrests were affected in Texas, but not fatality crashes. Significant to this study is the fact that although the number of arrests declined, the data showed after the McNeely ruling the decline in arrests, was more rapid. The number of impairment arrests in Texas annually prior to McNeely was an average of 89,473, which fell to an average of 70,438 after the ruling. Therefore, the effects of requiring a search warrant before collecting blood evidence produced an outcome of fewer impairment arrests by police officers. The results of the study indicated that there is a statistically significant relationship between impairment arrests and fatality crashes before and after the McNeely ruling in Texas. Finally, the results indicated that overall, Missouri v. McNeely had a significant effect on DWI arrests and fatal crashes in Texas.

LIMITATIONS

There are limitations to this study; the lack of uniformity in arrest procedures in the different counties, the population shift may have biased the average among the test area [13]. Considering the location of the county, natural disasters may have affected the number of arrests and fatality crashes during any given year tested. For example, Hurricane Rita (2005) caused mass evacuations of towns and cities in Louisiana. Those individuals were rehoused in cities throughout Texas, including Harris County.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Training officers as phlebotomist has been discussed with cautions and how law enforcement should confront these challenges [14]. It is imperative that all law enforcement agencies in Texas create a standardized DWI Unit to focus specifically on targeting impaired drivers before they have the opportunity to cause any crashes especially fatal crash. Officers should continuously receive the latest training necessary to detect and prosecute impaired drivers. Training should also involve the latest court rulings involving drunk driving arrests cases.

REFERENCES

- Schmitz M (2005) Are the odds ever in your favor? Car crashes versus other fatalities, Share.

- Fitzpatrick K, Harwood D W, Anderson IB, (2000) Accident mitigation guide for congested rural two lane highways. National Academy Pres,Washington, D.C., USA

- Harr JS, Hess KM, Orthmann CH, Kingsbury J. (2018). Constitutional law and the criminal justice system. Boston, MA, USA.

- Sherman LW (2018). Reducing fatal police shooting as system crashes: Research, theory, and practice. Annual Reviews 1: 421-449.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Department of Transportation (2017) USDOT Releases 2016 Fatal Traffic Crash Data.

- Kanovitz JR (2015) Constitutional law for criminal justice. New York, NY. Routledge.

- Beller AB (1991). United State v. MacDonald: The Exigent Circumstances Exception and the Erosion of the Fourth Amendment. Hofstra Law Review 20(2): 1 -22.

- Lee CF, Lee JC, Lee AC (2000). Statistics for business and financial economics. Springer. Volume 1. River Edge, NJ. World Scientific.

- Davis ES, Flores EN, Ignani, J, Opheim C, Wlezien C (2008) Texas politics today, Boston, MA, USA.

- Gaines LH, Miller RL (2009). Criminal justice in action. Belmont, CA.

- Grant DM, Tucker KG (2017). Texas d.w.i. manual. James Publishing, Inc. Costa, Mesa, CA.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation (2007 – 2016). Uniform crime reporting: UCR [Washington, D.C.]: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- Maslov A (2015). Measuring the performance of the police. Ottawa Ontario.

- Gutier A (2016) Law enforcement phlebotomy for safer roads. Washington, D.C, USA.

Citation: Mozayani A, Whitaker QV (2019) Arrests, Fatality Crashes, Before and After Missouri V Mcneely Law In Texas. J Forensic Leg Investig Sci 5: 024.

Copyright: © 2019 Quincy V Whitaker*, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.