A Review of Empirical Studies on the Views on the Criminalisation of STIs/HIV Transmission in the UK

Abstract

This paper reviews peer-reviewed empirical studies of the views on the criminalisation of STIs/HIV in the UK. The review examines the state of current research in British context and highlights gaps in existing literature. Findings indicate a lack of legal and health-related knowledge among people living with HIV, MSM and professionals working with people living with HIV and highlight specific challenges for key-populations.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Since 2001, there were thirty (30) convictions for STIs and HIV transmission in the UK; twenty-six (26) convictions under the Offences Against the Person Act (OAPA, 1861) in England and Wales; four (4) convictions under the Scottish Criminal Law in Scotland.The prosecution and the conviction of STI/HIV transmission adhere to specific rules and determined conditions (Law Commission, 2014; COPFS; 2014).

Pro-criminalisation arguments consider legal enforcement as a structural intervention likely to reduce the number of transmissions and as an individual punishment for harming another [7-10]. By contrast, the anti-criminalisation rationale has been based on the protection of human rights [11,12]. More recently, studies highlighted the deleterious impact of criminalisation laws (i.e., transmission of and exposure to HIV, non-disclosure of one’s HIV status laws) on public health goals (lack of preventive effect or deleterious effect, [13-16]) the perception of the health and well-being of people living with HIV and relationship with service providers [17-22]. Globally, it is argued that the people most vulnerable to acquiring HIV are already subject to legal and social oppression and criminalisation of HIV increases marginalization [23]. These include undocumented people, sex workers, substance misusers, ethnic minorities and sexual and gender minorities [24-32].

Since the first conviction in the UK, a number of studies investigated peoples’ opinions about the criminalisation of STIs/HIV and related themes (e.g., knowledge of criminal liability; disclosure of one’s status to sexual partner(s), concerns among people living with HIV, the impact of changes in community settings and/or professional practices). This is the first systematic review of empirical studies exploring views on the criminalisation of STIs/HIV in the UK. It aims to identify current trends in research and synthesise findings regarding the British population and context.

METHOD

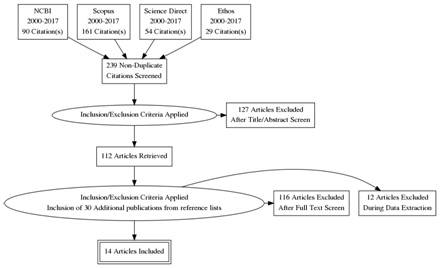

Sources and search strategy

Eligibility criteria

Data extraction

Biases

RESULTS

Articles retrieved

Characteristics of the studies included

|

REF |

Methods |

Sample (based on available data) |

Results/Main Findings (Summary and/or Verbatim from the publication)

|

|||||

|

# |

Authors, year, title |

Criminalisation as a primary or secondary outcome/topic |

Design and Method |

Analysis |

N |

|||

|

1 |

UK Coalition of People Living with HIV and AIDS [41] Criminalisation of HIV transmission: results of online and postal questionnaire survey. |

Primary Community survey |

Mixed |

Survey with MCQ |

Descriptive distribution and interpretation |

233 |

165 People living with HIV |

1)People living with HIV tend to be less pro-criminalisation 2)42% of the respondents consider intentional transmission should be criminalized 3)76% of the respondents consider convictions increase stigma |

|

68 Other |

||||||||

|

2 |

Dodds et al., [42] Criminal conviction for HIV transmission: people living with HIV respond. |

Primary Community response to HIV criminalisation Primary |

Qualitative |

20 FG |

Thematic analysis |

125 |

People living with HIV |

1) Dominant themes: shared responsibility and increase stigma 2) Secondary themes: questionable veracity of evidence and reliability of witnesses, Behaviour change implication and perception of racial bias in the judiciary system, negative press impact, and criminalisation as a way forward |

|

3/4 |

Weatherburn et al., [43] Multiple chances: findings from the United Kingdom Gay Men’s Sex Survey 2006. Dodds et al., [44] Homosexually active men's views on criminal prosecution for HIV transmission are related to HIV prevention need. |

Secondary focus (SIGMA Research) Yes/no question |

Mixed |

Survey with MCQ |

Descriptive distribution and interpretation |

8132 |

MSM 3369 MSM never tested for HIV 4218 MSM last tested negative 565 MSM living with HIV |

1) 21.3% knew that people with HIV had been imprisoned in the UK for passing their infection without intending to do so 2) 74.3% of all men expected HIV positive disclosure from potential sex partners 3) Lack of knowledge regarding criminalisation but also regarding HIV prevention transmission |

|

5 |

Bourne et al., [45] Relative Safety 2: Risk and unprotected al intercourse among gay men diagnosed with HIV. |

Primary focus: SIGMA Research Report Perception of risk and responsibility |

Qualitative |

Interview |

Thematic analysis |

42 |

MSM living with HIV Age range [18 ;58] 33 White/White British, 9 Other |

1) Risk calculation and risk management strategies (sex with other people living with HIV, previous online contact as an evidence of disclosure) 2) Fear of transmitting, fear/experiences of rejection when disclosure. Cautious behaviours, sex with other people living with HIV, online contact (evidence of disclosure) 3) Small proportion of people afraid of/ worried about super/co-infection 4) Harm to social and moral identity |

|

6 |

Dodds et al., [46] Sexually charged: the views of gay and bisexual men on criminal prosecution for sexual HIV transmission. |

Primary focus, secondary analysis: Views on criminalisation (sampled from Weatherburn et al., [43] SIGMA Research Report |

Mixed |

Survey with open ended question |

Thematic analysis |

6757 |

565 MSM living with HIV 3962 MSM pro criminalisation views 1121 MSM antic criminalisation views 1674 MSM unsure about their views |

1) Pro-criminalisation views were more common among men who were younger, had never had an HIV test, had lower levels of education, lived outside of London, reported sex with both men and women in the previous year, were not in a relationship with a man, and had lower numbers of male sexual partners 2) Anti-criminalisation views were more common among men living with HIV, living in England, especially London, being older, having university-level education, and a high number of male sexual partners in the previous year 3) No real factors associated with the unsure opinion |

|

7 |

Weatherburn et al., [47] What do you need? 2007-08 findings from an online survey of people with diagnosed HIV. |

Secondary SIGMA Research Report Needs of people living with HIV |

Mixed |

Survey |

Descriptive distribution and interpretation |

1777 |

1777 People living with HIV 1359 males / 351 females Age range [17 ;78] 1180 White/White British / 597 Other |

1) 32% have concerns about potential prosecution for onward transmission of HIV during sex 2) Some respondents said criminal prosecution for sexual HIV transmission and the threat of deportation hindered disclosure and distilled fear 3) Fear of friendships becoming relationships with potential for sex and onward HIV transmission 4) Sero-discordant relationships were especially fraught about sex, with a wide range of anxieties about HIV transmission reported |

|

8 |

Dodds et al., [48] Responses to criminal prosecution for HIV transmission among gay men with HIV in England and Wales. |

Primary Research paper : Impact on lived experiences of people living with HIV |

Qualitative |

Interview |

Thematic analysis |

42 |

MSM living with HIV |

1) Knowledge: 1/3 men in the sample articulated awareness of, and accurately expressed the matters, which the prosecution has to prove. Nonetheless, their understanding sometimes contained key flaws 2) Altered behaviours and revised meanings: Several men feared condemnation from their local gay community should it become known that they had engaged in unprotected sex as a diagnosed man, particularly if that sex resulted in transmission of HIV. These findings demonstrate some of the key challenges in seeking to influence human behaviour |

|

9 |

Rodohan et al., [49] Criminalisation for sexual transmission of HIV. Emerging issues and the impact upon clinical psychology practice in UK. |

Primary Doctoral Dissertation |

Quantitative |

Survey |

Parametric and cluster analysis |

107 |

Professionals 22 males / 84 females Age range [26 ;77] 104 White/White British / 3 Other |

1) Fear of litigation and problem regarding confidentiality (subpoena for one participant) 2) Professional liability, dilemma between duty of care and policing 3) Tendency to inform patients, encourage and support disclosure and keep track of information given 4) Legal guidance needed |

|

Qualitative |

3 FG |

IPA |

15 |

Professionals |

||||

|

10 |

Bourne et al., [50] Problems with sex among gay and bisexual men with diagnosed HIV in the United Kingdom. |

Secondary Sexuality and sexual health of MSM living with HIV Research paper from SIGMA Research |

Quantitative |

Survey |

Standardized items and factor analysis |

1217 |

MSM living with HIV Age range [17 ;76] 1146 White British / 71 Other |

1) Worries about prosecution/criminalisation of HIV transmission 24.2% 2) Worries about passing HIV to partners 37.3% 3) Fear of rejection from potential partners 34.7% 4) Worries about disclosing HIV to partners 31.8% 5) Desire for clearer guidance for men, their sexual partners, and health professionals about how and why such prosecution operate. Most were critical of the use of the criminal law and the consequences for risk negotiation |

|

11 |

Wayal et al., [51] Sexual networks, partnership patter and behaviour of HIV positive men who have sex with men: implication for HIV/STIs transmission and partner notification. |

Secondary Doctoral Dissertation |

Qualitative |

Interview |

Thematic analysis |

24 |

MSM living with HIV |

1) This is the first study in the UK to show that the fear of being criminalized for HIV transmission can be a barrier to notifying partners of STI, especially casual partners in circumstances of non-disclosure of HIV status |

|

12 |

Phillips et al., [52] Narratives of HIV: measuring understanding of HIV and the law in HIV-positive patients. |

Primary Research paper |

Qualitative |

Interview |

Thematic analysis |

33 |

People living with HIV 28 males / 5 females Age range [19;53] 22 White or White British / 11 Other |

1) Knowledge of the Law without understanding its application (e.g. personal vs legal definition of intention) 2) Moral obligation to prevent transmission onward 3) Needs assessment for tailored needs function to the level of knowledge and the level of risks of transmission |

|

13 |

Dodds et al., [53] Keeping confidence: HIV and the criminal law from HIV service providers’ perspectives. |

Primary Research paper |

Qualitative |

12 FG |

Thematic analysis |

75 |

Professionals 53 health professionals 33 community professionals (double affiliation) |

1) Basic knowledge but confusion about legal meaning 2) Dilemma between duty of care and moral implications 3) Fear of liability, increase track record when information and advice given by the professional 4) Need for skill-building capacity, promotion of disclosure and self-acceptance |

|

14 |

Jelliman et al., [54] HIV is now a manageable long-term condition, but what makes it unique? A Qualitative Study Exploring Views About Distinguishing Features from Multi-Professional HIV Specialists in North West England. |

Secondary Research paper Professionals' views on HIV specific features as a long-term condition |

Qualitative |

3 FG |

Thematic analysis |

24 |

Professionals 5 males 19 females 11 health professionals 13 community professionals |

1) Participants agreed that the law was unhelpful, potentially traumatic for patients, and harmful to public health 2) Criminalisation contributes to the exceptionalism of HIV (stand-alone features) |

Number of studies retrieved

AIM

Theoretical background

Sample, method and design

POPULATION

|

Sociodemographic characteristicsa of |

Total / Estimation people |

Gender |

Sexual orientation |

Ethnicityb |

|||||

|

N |

Living with HIV |

Not living with HIV |

Male |

Female |

LGB and MSM |

White British |

Other |

||

|

% |

|||||||||

|

People living with HIV |

2015 |

101200 |

101200 |

Not applicable |

61097 |

27672 |

41016 |

48447 |

40322 |

|

% |

100% |

69% |

31% |

46% |

55% |

45.42% |

|||

|

People newly diagnosed with HIV |

2016 |

5164 |

5164 |

3939 |

1226 |

2810 |

2449 |

2241 |

|

|

% |

100% |

76% |

24% |

54% |

52% |

48% |

|||

|

2015 |

6095 |

6095 |

4551 |

1537 |

3320 |

3269 |

2704 |

||

|

% |

100% |

75% |

25% |

54% |

54% |

44% |

|||

|

2014 |

6172 |

6172 |

4619 |

1551 |

3360 |

3468 |

2704 |

||

|

% |

100% |

75% |

25% |

54% |

56% |

43% |

|||

|

2006 |

7439 |

7439 |

4499 |

2940 |

2670 |

3165 |

29965 |

||

|

% |

100% |

60% |

40% |

35% |

43% |

57% |

|||

|

STIs/HIV Convictions |

Defendants |

30 |

27 |

3 |

28 |

2 |

3 |

16 |

14 |

|

2001-2017c |

% |

90% |

9% |

93% |

7% |

10% |

52% |

48% |

|

|

|

Complainants |

50 |

41 |

9 |

15 |

35 |

13 |

Incomplete data |

|

|

|

% |

82% |

18% |

30% |

70% |

26% |

|||

|

|

Total |

80 |

68 |

11 |

43 |

37 |

16 |

||

|

|

% |

85% |

15% |

54% |

46% |

20% |

|||

|

Population from the systematic review |

10 597 |

2731 |

7856 |

9621 |

468 |

8333 |

7483 |

2628 |

|

|

% |

26% |

74% |

91% |

4% |

79% |

71% |

25% |

||

Note.

aData were retrieved from Public Health England https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hiv-annual-data-tables. Complements were retrieved: as to 2014 and 2006 from Skingsley et al., [3]; as to 2015 statistics from Kirwan et al., [2]; as to 2016 figures from National HIV surveillance data tables

bEthnicity was unknown or not reported in 9% of the sample, percentage are based on the available data

CWebsites (e.g. www.hivjustice.net) and national newspapers, and legal databases: www.lexisnexis.com, http://www.bailii.org/databases.html#ew, and http://www.lawpages.com

FINDINGS

Despite the different aims and sample characteristics, four key themes were identified across studies: ‘knowledge of the law’, ‘explicit opinions on criminalisation’, ‘explicit opinions on disclosure’ and ‘morality’ (e.g., moral agency, moral dilemma). The synthesis of this review is presented for each population identified in the reviewed studies.

PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV

The daily management of HIV as a long-term condition weighed towards the daily management of risks. People living with HIV used different strategies to either handle situations where there was a risk of transmission or prevent possible prosecutions [45]. For instance, the disclosure of one’s serostatus online was frequently used as previous evidence of disclosure. However, such a strategy was only relevant for people who had a clear and comprehensive understanding of the prosecution criteria. Importantly, most of the people living with HIV in this review did not have a full understanding of the legal aspects of transmission [46,52]. While concepts such as intention, harm and recklessness were clearly defined from a legal point of view, people living with HIV largely defined this concept from an individual or psychological point of view.

Stances on disclosure and individual responsibility showed the dual burden criminalisation leads to. Disclosure was a feared moment (e.g., rejection) and fear of criminalisation was seen as a barrier to the disclosure of HIV status to potential sexual partners [47,51]. By contrast, disclosure was sometimes viewed as the responsibility of the person living with HIV (the onus of not transmitting HIV to a partner) rather than for the partner to take action to protect themselves [43,44]. The shared responsibility was mentioned by participants across studies [42,43,46]. Such a stance illustrates a social shift in how sexual and intimate relationships were constructed, in the sense that the assumption that the other person is HIV-negative is too uncertain and might not be valid anymore. Finally, four studies reported views that criminalisation increased stigma and harmed social identity [41,42,45,46].

MEN WHO HAVE SEX WITH MEN (MSM)

Professionals working with people living with HIV

LIMITATIONS

Number of studies

Population and representativity

Secondly, the overrepresentation of (male) defendants coming from ethnic minorities suggests the possible intersection of cumulative attributes. At the intersection of crime, ethnicity or citizenship background and HIV, legal decisions and media portrayals seemed to have led to the construction of a stereotype: The Black man living with HIV infecting the British woman [61]. Though, this population was under-represented in the population of the systematic review.

Thirdly, the overrepresentation of MSM in the population studied and the underrepresentation of the MSM population in conviction cases compared to the MSM living with HIV must be noted. Two aspects should be considered. On the one hand, specific research and information related to the legal proceedings engaged by MSM living with HIV as it remains unknown if same-sex transmission of HIV is less filed against, less prosecuted, or less convicted. On the other hand, given the early mobilisation of the community in the fight against AIDS, the perception of risk and HIV may differ from other communities or even divide the community explaining potential different attitudes [62-66].

FURTHER RESEARCH

Studies reporting stigma as a major concern were mostly based on people living with HIV. Furthermore, while the majority of the studies emphasize that criminalisation feeds HIV-stigma, whether invoked (argument) or reported (lived experiences), no studies provided comparable empirical measures. While this construct appears to be a valid theoretical and logical statement, it may require further investigation and a context-sensitive approach. Future studies may shed greater light on the relationship between views of the criminalization of HIV and HIV-related stigma. Despite the structural and legal differences, examining other national contexts with a high number of convictions (e.g. Sweden, Canada, and USA) is likely to inform on the impact of criminal policies and to provide further insights into connected areas such as the criminalisation of exposure to and non-disclosure of HIV [67].

CONCLUSION

Globally, the population sampled was sympathetic to the criminalisation of intentional transmission but remain undecided on other circumstances. The popular and legal concepts of intention differ. The popular understanding of intentional transmission relies on the deliberate intention to transmit the virus, not on the absence of protective measures and/or disclosure. The ambiguity of the concept of intention in laymen terms and in specific fields should, therefore, be elicited. Contingent themes, such as disclosure and responsibility, summarise the emotional, relational and professional challenges, faced by the populations sampled. Main information needs identified were legal guidance and support for people living with HIV and professionals, and legal and sexual health-related information for MSM.

REFERENCES

- Public Health England (2017) Sexually Transmitted Infections and Chlamydia Screening in England, 2016: Health Protection Report. Public Health England (Vol 11), London, UK.

- Kirwan PD, Chau C, Brown AE, Gill ON, Delpech VC, et al. (2016) HIV in the UK 2016 report. Public Health England, London, UK.

- Skingsley A, Kirwan P, Yin Z, Nardone A, Hughes G, et al. (2015) HIV New Diagnoses, Treatment and Care in the UK 2015 report. Public Health England, London, UK.

- Skingsley A, Yin Z, Kirwan P, Croxford S, Chau C, et al. (2015) HIV in the UK – Situation Report 2015 Incidence, prevalence and prevention: The second of two complementary reports about HIV in the UK in 2015. Public Health England, London, UK.

- Public Health England (2017) HIV in the United Kingdom: decline in new HIV diagnoses in gay and bisexual men in London, 2017 report. Health Protection Report (Vol 11), Public Health England, London, UK.

- Law Commission (2014) Reform of offences against the person: A Scoping Consultation Paper. Law Commission, London, UK.

- Hermann DH (1990) Criminalizing conduct related to HIV transmission. St Louis Univ Public Law Rev 9: 351-378.

- van Wyk C (2000) The need for a new statutory offence aimed at harmful HIV-related behaviour: The general public interest perspective. Codicillus 41: 2-10.

- Francis AM, Mialon HM (2008) The optimal penalty for sexually transmitting HIV. American Law and Economics Review 10: 388-423.

- Mathen C, Plaxton M (2011) HIV, Consent and Criminal Wrongs. Criminal Law Quarterly 57: 464-485.

- Mann JM (1992) AIDS and human rights. Health and Human Rights 3: 143-149.

- Cameron E (1993) Legal rights, human rights and AIDS: the first decade. Report from South Africa 2. AIDS Anal Afr 3: 3-4.

- Mykhalovskiy E (2011) The problem of "significant risk": exploring the public health impact of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure. Soc Sci Med 73: 668-675.

- O'Byrne P, Willmore J, Bryan A, Friedman DS, Hendriks A, et al. (2013) Nondisclosure prosecutions and population health outcomes: examining HIV testing, HIV diagnoses, and the attitudes of men who have sex with men following nondisclosure prosecution media releases in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Public Health 13: 94.

- WHO (2015) Sexual health, human rights and the law. WHO, Geneva, Swizerland.

- Sweeney P, Gray SC, Purcell DW, Sewell J, Babu AS, et al. (2017) Association of HIV diagnosis rates and laws criminalizing HIV exposure in the United States. AIDS 31: 1483-1488.

- Horvath KJ, Weinmeyer R, Rosser S (2010) Should it be illegal for HIV-positive persons to have unprotected sex without disclosure? An examination of attitudes among US men who have sex with men and the impact of state law. AIDS care 22: 1221-1228.

- O'Byrne P, Bryan A, Roy M (2013) HIV criminal prosecutions and public health: an examination of the empirical research. Med Humanit 39: 85-90.

- Phillips JC, Webel A, Rose CD, Corless IB, Sullivan KM, et al (2013) Associations between the legal context of HIV, perceived social capital, and HIV antiretroviral adherence in North America. BMC Public Health 13: 736.

- Gruskin S, Ferguson L, Alfven T, Rugg D, Peersman G (2014) Identifying structural barriers to an effective HIV response: using the National Composite Policy Index data to evaluate the human rights, legal and policy environment. J Int AIDS Soc 16: 18000.

- Patterson SE, Milloy M-J, Ogilvie G, Greene S, Nicholson V, et al. (2015) The impact of criminalization of HIV non-disclosure on the healthcare engagement of women living with HIV in Canada: a comprehensive review of the evidence. J Int AIDS Soc 18: 20572.

- Savage S, Braund R, Stewart T, Brennan DJ (2017) How could I tell them that it's going to be okay? The impact of HIV nondisclosure criminalization on service provision to people living with HIV. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services 16: 287-300.

- Perone A (2013) From punitive to proactive: An alternative approach for responding to HIV criminalization that departs from penalizing marginalized communities. Hastings Women’s Law Journal 24: 363.

- Deblonde J, Sasse A, Del Amo J, Burns F, Delpech V, et al. (2015) Restricted access to antiretroviral treatment for undocumented migrants: a bottle neck to control the HIV epidemic in the EU/EEA. BMC Public Health 15: 1228.

- Baral SD, Friedman MR, Geibel S, Rebe K, Bozhinov B, et al. (2015) Male sex workers: practices, contexts, and vulnerabilities for HIV acquisition and transmission. Lancet 385: 260-273.

- Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, Mwangi P, et al. (2015) Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet 385: 55-71.

- Reeves A, Steele S, Stuckler D, McKee M, Amato-Gauci A, et al. (2017) National sex work policy and HIV prevalence among sex workers: an ecological regression analysis of 27 European countries. Lancet HIV 4: 134-140.

- Csete J, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, Altice F, Balicki M, et al. (2016) Public Health and International Drug Policy. Lancet 387: 1427-1480.

- Gwadz M, Cleland CM, Hagan H, Jenness S, Kutnick A, et al. (2015) Strategies to uncover undiagnosed HIV infection among heterosexuals at high risk and link them to HIV care with high retention: a "seek, test, treat, and retain" study. BMC Public Health 15: 481.

- Carroll A (2016) State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition. International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), Genebra, Switzerland.

- Rodriguez NS (2016) Communicating global inequalities: How LGBTI asylum-specific NGOs use social media as public relations. Public Relations Review 42: 322-332.

- Ahmed A, Kaplan M, Symington A, Kismodi E (2011) Criminalising consensual sexual behaviour in the context of HIV: consequences, evidence, and leadership. Glob Public Health 6: 357-369.

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, et al. (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 350: 7647.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, et al. (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4: 1.

- Walsh D, Downe S (2005) Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 50: 204-211.

- Paterson BL, Thorne SE, Canam C, Jillings C (2001) Meta-study of qualitative health research: a practical guide to meta-analysis and metasynthesis. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, USA.

- Dixon-Woods M, Fitzpatrick R, Roberts K (2001) Including qualitative research in systematic reviews: opportunities and problems. J Eval Clin Pract 7: 125-133.

- Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Kippen S, Liamputtong P (2007) Doing sensitive research: what challenges do qualitative researchers face?. Qualitative research 7: 327-353.

- Tourangeau R, Yan T (2007) Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull 133: 859-883.

- Krumpal I (2013) Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Quality & Quantity 47: 2025-2047.

- UK Coalition of People Living with HIV & AIDS (2005) criminalisation of HIV transmission results of online and postal questionnaire survey. UK Coalition of People Living with HIV & AIDS, London, UK.

- Dodds C, Keogh P (2006) Criminal prosecutions for HIV transmission: people living with HIV respond. Int J STD AIDS 17: 315-318.

- Weatherburn P, Hickson F, Reid D, Jessup K, Hammond G (2008) Multiple chances - Findings from the United Kingdom Gay Men’s Sex Survey 2006. Sigma Research, London, UK.

- Dodds C (2008) Homosexually active men's views on criminal prosecution for HIV transmission are related to HIV prevention need. AIDS care 20: 509-514.

- Bourne A, Dodds C, Keogh P, Weatherburn P, Hammond G (2009) Relative Safety 2: Risk and unprotected anal intercourse among gay men diagnosed with HIV. Sigma Research, London, UK.

- Dodds C, Weatherburne P, Bourne A, Hammond G, Weait M, et al. (2009) Sexually charged: the views of gay and bisexual men on criminal prosecution for sexual HIV transmission. Sigma Research, London, UK.

- Weatherburn P, Keogh P, Reid D, Dodds C, Bourne A, et al. (2009) What do you need? 2007-08 - Findings from a national survey of people with diagnosed HIV. Sigma Research, London, UK.

- Dodds C, Bourne A, Weait M (2009) Responses to criminal prosecutions for HIV transmission among gay men with HIV in England and Wales. Reprod Health Matters 17: 135-145.

- Rodohan E (2010) Criminalisation for sexual transmission of HIV : emerging issues and the impact upon clinical psychology practice in the UK. University of Hertfordshire, UK.

- Bourne A, Hickson F, Keogh P, Reid D, Weatherburn P (2012) Problems with sex among gay and bisexual men with diagnosed HIV in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health 12: 916.

- Wayal S (2013) Sexual networks, partnership patterns and behaviour of HIV positive men who have sex with men: implications for HIV/STIs transmission and partner notification. University College London, London, UK.

- Phillips MD, Schembri G (2015) Narratives of HIV: measuring understanding of HIV and the law in HIV-positive patients. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 0: 1-6.

- Dodds C, Weait M, Bourne A, Egede S (2015) Keeping confidence: HIV and the criminal law from HIV service providers’ perspectives. Crit Public Health 25: 410-426.

- Jelliman P, Porcellato L (2017) HIV is Now a Manageable Long-Term Condition, But What Makes it Unique? A Qualitative Study Exploring Views About Distinguishing Features from Multi-Professional HIV Specialists in North West England. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 28: 165-178.

- Paiva V, Ferguson L, Aggleton P, Mane P, Kelly-Hanku A, et al. (2015) The current state of play of research on the social, political and legal dimensions of HIV. Cad Saude Publica 31: 477-486.

- Carmo R, Grams A, Magalhães T (2011) Men as victims of intimate partner violence. J Forensic Leg Med 18: 355-359.

- Dutton DG, Nicholls TL, University of British Columbia (2005) The gender paradigm in domestic violence research and theory: Part 1—The conflict of theory and data. Aggression and Violent Behavior 11: 680-714.

- Tsui V, Cheung M, Leung P (2010) Help-seeking among male victims of partner abuse: men's hard times. Journal of Community Psychology 38: 769-780.

- Schellenberg EG, Keil JM, Bem SL (1995) “Innocent Victims” of AIDS: Identifying the Subtext. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 25: 1790-1800.

- Blumenreich M, Siegel M (2006) Innocent Victims, Fighter Cells, and White Uncles: A Discourse Analysis of Children’s Books about AIDS. Children's Literature in Education 37: 81-110.

- Persson A, Newman C (2008) Making monsters: heterosexuality, crime and race in recent Western media coverage of HIV. Sociol Health Illn 30: 632-646.

- Trapence G, Collins C, Avrett S, Carr R, Sanchez H, et al. (2012) From personal survival to public health: community leadership by men who have sex with men in the response to HIV. Lancet 380: 400-410.

- Courtenay-Quirk C, Wolitski RJ, Parsons JT, Gómez CA; Seropositive Urban Men's Study Team (2006) Is HIV/AIDS stigma dividing the gay community? Perceptions of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev 18: 56-67.

- MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Secura GM, Behel S, Bingham T, et al. (2007) Perceptions of lifetime risk and actual risk for acquiring HIV among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 11: 263-270.

- Clifton S, Nardone A, Field N, Mercer CH, Tanton C, et al. (2016) HIV testing, risk perception, and behaviour in the British population. AIDS 30: 943-952.

- Chard AN, Metheny N, Stephenson R (2017) Perceptions of HIV Seriousness, Risk, and Threat Among Online Samples of HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex With Men in Seven Countries. JMIR Public Health Surveill 3: 37.

- Burris S, Beletsky L, Burleson JA, Case P, Lazzarini Z (2007) Do Criminal Laws Influence HIV Risk Behavior? An Empirical Trial. Arizona State Law Journal 39: 467.

Citation: Chollier M, Tomkinson CT (2018) A Review of Empirical Studies on the Views on the Criminalisation of STIs/HIV Transmission in the UK. J AIDS Clin Res Sex Transm Dis 5: 017.

Copyright: © 2018 Marie Chollier, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.